Download Publication As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Herald International Law&Business Business New S in T E R

1 digest nationaL economic reLations Law&business business news internationaL ter n i s w e n s s e n i s u b s s e n i s u b & w a E L C STRY U ND I CHAMBER COMMER OF AND UKRAINIAN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS HERALD business news ing for the new markets, the Klei UKRAINE AND SAUDI ARABIA struction cost is estimated at 700-800 Adhesive Machinery implements the WILL JOINTLY CONSTRUCT AIR- mln dollars. international quality standards, ISO PLANES The Ukrlandfarming structure 9001 including, and develops pro- includes 111 horizontal grain storage duction. «Taqnia Aeronotics», a daughter facilities, 6 seed plants, 6 enimal feed entity of the Saudi company for de- plants, 6 sugar plants and 2 leather The main field of the company activity – supply of hi-tech equipment velopment and investments and «An- producing plants as well as an egg to glue various materials. The com- tonov» State company have signed products plant «Imperovo Foods», 19 pany designers develop machines the agreement on development and poultry-breeding plants, 9 hen farms, according to the client requirements production of the light transport plane 3 poultry farms, 3 selection breeding and their high-class specialists ma- An- 132 in Saudi Arabia. The main farms, 3 long-term storage facilities terialize their ideas in metal. That’s goal of the agreement is to fulfill a and 19 meat-processing plants. number of tasks in aviation construc- why the company machines meet tion and technology transfer to Saudi the world requirements. But they are Arabia as well as to train Saudi per- much cheaper. -

European Business Club

ASSOCIATION АССОЦИАЦИЯ OF EUROPEAN BUSINESSES ЕВРОПЕЙСКОГО БИЗНЕСА РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 127473 Москва ул. Краснопролетарская, д. 16 стр. 3 Ulitsa Krasnoproletarskaya 16, bld. 3, Moscow, 127473 Тел. +7 495 234 2764 Факс +7 495 234 2807 Tel +7 495 234 2764 Fax +7 495 234 2807 [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru 12th May, 2012 Moscow PRESS RELEASE The Year Continues Strong for New Cars and Light Commercial Vehicles in Russia • Sales of new passenger cars and LCVs in Russia increased by 14% in April, 2012 • Among the top ten bestselling models so far, ten are locally produced According to the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee (AEB AMC), April, 2012 saw the sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increase by 14% in comparison to the same period in 2011. This April, 266,267 units were sold; this is 33,189 units more than in April, 2011. From January to April, 2012 the percentage sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increased by 18% in comparison to the same period in 2011 or by 135,066 more sold units. David Thomas, Chairman of the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee commented: "The solid growth of the Russian automotive market continues into the second quarter. Although the pace of the year on year growth is stabilising to less than 15% in recent months, we still feel that the AEB full year forecast for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles should be increased by 50,000 units to 2.85 mln." -------------------------------------------------------------- Attachments: 1. -

Impact of Political Course Shift in Ukraine on Stock Returns

IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Economic Analysis Kyiv School of Economics 2014 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Approved by ___________________________________________________ Head of the KSE Defense Committee, Professor Irwin Collier __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Date ___________________________________ Kyiv School of Economics Abstract IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Since achieving its independence from the Soviet Union, Ukraine has faced the problem which regional block to integrate in. In this paper an event study is used to investigate investors` expectations about winners and losers from two possible integration options: the Free Trade Agreement as a part of the Association Agreement with the European Union and the Custom Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. The impact of these two sudden shifts in the political course on stock returns is analyzed to determine the companies which benefit from each integration decisions. No statistically significant impact on stock returns could be detected. However, our findings suggest a large positive reaction of companies` stock prices to the dismissal of Yanukovych regime regardless of company`s trade orientation and political affiliation. -

![Pdf [2019-05-25] 21](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2261/pdf-2019-05-25-21-742261.webp)

Pdf [2019-05-25] 21

ISSN 1648-2603 (print) VIEŠOJI POLITIKA IR ADMINISTRAVIMAS ISSN 2029-2872 (online) PUBLIC POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION 2019, T 18, Nr. 3/2019, Vol. 18, Nr. 3, p. 46-58 The World Experience and a Unified Model for Government Regulation of Development of the Automotive Industry Illia A. Dmytriiev, Inna Yu. Shevchenko, Vyacheslav M. Kudryavtsev, Olena M. Lushnikova Department of Economics and Entrepreneurship Kharkiv National Automobile and Highway University 61002, 25 Yaroslav Mudriy Str., Kharkiv, Ukraine Tetiana S. Zhytnik Department of Social Work, Social Pedagogy and Preschool Education Bogdan Khmelnitsky Melitopol State Pedagogical University 72300, 20 Hetmanska Str., Melitopol, Ukraine http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.ppaa.18.3.24720 Abstract. The article summarises the advanced world experience in government regulation of the automotive industry using the example of the leading automotive manufacturing countries – China, Japan, India, South Korea, the USA, and the European Union. Leading approach to the study of this problem is the comparative method that has afforded revealing peculiarities of the primary measures applied by governments of the world to regulate the automotive industry have been identified. A unified model for government regulation of the automotive industry has been elaborated. The presented model contains a set of measures for government support for the automotive industry depending on the life cycle stage (inception, growth, stabilisation, top position, stagnation, decline, crisis) of the automotive industry and the -

Statistical Testing of Key Effectiveness Indicators of the Companies (Case for Ukraine in 2012)

1 Vladimir Ponomarenko ГОДИНА XXIII, 2014, 4 Iryna Gontareva2 Oleksandr Dorokhov3 STATISTICAL TESTING OF KEY EFFECTIVENESS INDICATORS OF THE COMPANIES (CASE FOR UKRAINE IN 2012) The system efficiency of the company functioning depends on the quality potential, level of functional organization and operativeness of management decisions. All these aspects need to be shown results indicators of enterprises. Under effectiveness is to be understood the degree of achieve of the strategic goals of the enterprises. The most well-known base of the company functioning evaluating is model of balanced scorecard (BSC) of R. Kaplan and D. Norton. This system includes four aspects: financial, customer, internal business processes, training and development of staff. The purpose of this paper is the statistical testing of possibility to separate key effectiveness indicators for these groups and determination of their composition. With the use of multivariate factor analysis was identified the most significant indicators of the effectiveness of engineering companies. The hypothesis of R. Kaplan and D. Norton about the allocation of the four groups of key effectiveness indicators has been confirmed. JEL: C4; D2; O25 1. Introduction The system efficiency of the company functioning depends on the quality potential, level of functional organization and operativeness of management decisions. All these aspects need to be shown in results indicators of enterprises [1]. Effectiveness of enterprises depends on the level of conformity the real or possible results and goals, i.e. the degree of achievement of the strategic goals of enterprise functioning. For any company the result has the life cycle and goes through three phases: a) the desired result, , i.e. -

EAVEX Daily ENG Oct 13.Indd

Market Monitor October 13, 2011 Market Update STOCK MARKET PERFORMANCE Equity UX Index RTS Index* WIG 20 Index* 2,500 Local stocks again lagged strong gains seen on European bourses on 2,250 Wednesday (Oct 12), as Ukraine continued to receive a dressingdown from EU leaders over the conviction of former PM Yulia Tymoshenko. 2,000 The approval by Slovakia’s parliament of an increase in the EU’s bank 1,750 bailout fund fueled a rise of more than 2% in Frankfurt and Paris, 1,500 while the UX index managed a gain of only 0.5% to 1,327 points. The 1,250 11-Jul 25-Jul 8-Aug 22-Aug 5-Sep 19-Sep 3-Oct day’s best performer was volume leader Motor Sich, which added * rebased 1.5% on turnover of UAH 13mn. Other top liquid names, including CentrEnergo, Alchevsk Steel, Azovstal, and Ukrsotsbank, were up MARKET INDEXES by between 0.5% and 1%. In London, Ferrexpo continued its strong Last 1D ch 1M ch YTD rebound on fading global recession fears, picking up another 7.9% to UX 1326.4 0.7% 12.7% 45.7% RTS 1407.8 3.9% 13.4% 20.5% USD 3.30. WIG20 2316.7 2.4% 3.0% 15.6% MSCI EM 923.2 1.5% 7.0% 19.8% Fixed Income S&P 500 1207.3 1.0% 4.6% 4.0% Ukrainian sovereign Eurobonds saw a broad rebound on Wednesday. Ukrainian midterm Eurobonds added 2.0p.p. 84.0/88.0 UX INTRADAY OCTOBER 12, 2011 (10.70%/9.58%), while longterms rose by 4.0p.p. -

2017 Annual Report Çâ³ò

Annual 2017 report 2017 2 UKRGASBANK 3 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Brand Identity ................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. Composition of the Supervisory Board of UKRGASBANK .....................................8 1.2. Composition of the Board (as of 01.01.2018) .....................................................9 1.3. Bank Executives, Non-Members of the Board (as of 01.01.2018) .....................11 1.4. Mission. Strategic Goals. Strategy for 2018 .......................................................12 1.5. ECO-Banking Implementation ............................................................................13 1.6. Licences and Permits .........................................................................................17 1.7. Affiliated Persons ...............................................................................................19 1.8. Organizational Framework (as of 01.01.2018) ..................................................20 1.9. Personnel ...........................................................................................................22 1.10. Our History ..........................................................................................................23 1.11. Ratings ...............................................................................................................31 1.12. Financial Indicators Overview for 2017 ..............................................................34 1.13. Membership -

Lutsk Intercultural Profile

City of Lutsk Intercultural Profile This report is based upon the visit of the CoE expert team on 1-4 July 2017, comprising Kseniya Khovanova-Rubicondo and Phil Wood. It should ideally be read in parallel with the Council of Europe’s response to Odessa’s ICC Index Questionnaire but, at the time of writing, the completion of the Index by the City Council is still a work in progress. 1. Introduction Lutsk lies in northwestern Ukraine not far from the borders with Poland and Belarus, and has a population of 217,103 (2015 est.). It was the main centre of the historic region of Volhynia and is now the administrative centre of the Volyn Oblast (population 1,036,891[2005]). Lutsk has the status of a city of oblast significance. A complex history of conquest and shifting borders has seen it part of Lithuania, Russia, Poland, the Soviet Union as well as Ukraine, giving the area a rich cultural heritage. Lutsk itself is built upon an appreciation of migration and diversity. King Vytautas the Great founded the town itself by importing colonists (mostly Jews, Tatars, and Karaims). The town grew rapidly, and by the end of the 15th century there were 19 Orthodox and two Catholic churches. In 1939 Lutsk was a prosperous city with a multiethnic population of which Jews and Poles were the largest groups, but invasion by the Soviet Union and then by Germany proved a disaster, with mass deportations and murders over almost a decade, by the end of which Lutsk was ethnically an almost exclusively Ukrainian city. -

Project Document

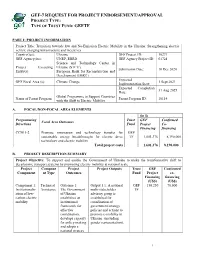

GEF-7 REQUEST FOR PROJECT ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEFTF PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Transition towards low and No-Emission Electric Mobility in the Ukraine: Strengthening electric vehicle charging infrastructure and incentives Country(ies): Ukraine GEF Project ID: 10271 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP, EBRD GEF Agency Project ID: 01724 Science and Technology Center in Project Executing Ukraine (STCU), Submission Date: 10 Dec 2020 Entity(s): European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Expected GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change 1 Sept 2021 Implementation Start: Expected Completion 31 Aug 2025 Date: Global Programme to Support Countries Name of Parent Program Parent Program ID: 10114 with the Shift to Electric Mobility A. FOCAL/NON-FOCAL AREA ELEMENTS (in $) Programming Trust GEF Confirmed Focal Area Outcomes Directions Fund Project Co- Financing financing CCM 1-2 Promote innovation and technology transfer for GEF sustainable energy breakthroughs for electric drive TF 1,601,376 8,190,000 technology and electric mobility Total project costs 1,601,376 8,190,000 B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To support and enable the Government of Ukraine to make the transformative shift to decarbonize transport systems by promoting electric mobility at national scale Project Compone Project Project Outputs Trust GEF Confirmed Component nt Type Outcomes Fund Project co- Financing financing (US$) (US$) Component 1: Technical Outcome 1: Output 1.1: A national GEF 150,250 70,000 Institutionaliz Assistance The Government multi-stakeholder TF ation of low- of Ukraine advisory group is carbon electric establishes an established for mobility institutional coordination of framework for government strategy, effective policies and actions to coordination, promote e-mobility in develops capacity Ukraine. -

European Business Club

ASSOCIATION АССОЦИАЦИЯ OF EUROPEAN BUSINESSES ЕВРОПЕЙСКОГО БИЗНЕСА РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 127473 Москва ул. Краснопролетарская, д. 16 стр. 3 Ulitsa Krasnoproletarskaya 16, bld. 3, Moscow, 127473 Тел. +7 495 234 2764 Факс +7 495 234 2807 Tel +7 495 234 2764 Fax +7 495 234 2807 [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru 11th March, 2012 Moscow PRESS RELEASE The Year Continues Strong for New Cars and Light Commercial Vehicles in Russia • Sales of new passenger cars and LCVs in Russia increased by 25% in February, 2012 • Among the top ten bestselling models so far, ten are locally produced According to the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee (AEB AMC), February, 2012 saw the sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increase by 25% in comparison to the same period in 2011. This February, 206,873 units were sold; this is 40,718 units more than in February, 2011. Among the top ten bestselling models of passenger cars so far, ten are produced in Russia. January and February 2012 saw the percentage sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increase by 23% in comparison to the same period in 2011 or by 66,867 more sold units. David Thomas, Chairman of the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee commented: “The encouraging start to 2012 continues with 25% growth for the month following January's 20% increase. A 23% Year to date increase is better than anticipated in the last AMC forecast, but as the first two months in the Russian market are subject to vacations and the impact of closing stocks, it is too early to revise our full year view of 2.8m Passenger Cars and Light commercial Vehicles. -

P&A Plants A4 2013 by MANUFACTURER Web

AUTOMOBILE ASSEMBLY & ENGINE PRODUCTION PLANTS IN EUROPE BY MANUFACTURER Type produced Plant location Manufacturer Brand Engine PC LCV CV Bus ACEA MEMBERS BMW GROUP AT-Austria Steyr BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Dingolfing BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Leipzig BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Munich BMW GROUP BMW DE-Germany Regensburg BMW GROUP BMW UK-United Kingdom Cowley (Oxford) BMW GROUP Mini UK-United Kingdom Goodwood BMW GROUP Rolls Royce UK-United Kingdom Hams Hall BMW GROUP Facilities not owned / operated by BMW AT-Austria Graz BMW GROUP Mini at MAGNA STEYR plant NL-Netherlands Born BMW GROUP Mini at VDL plant (from 2014) RU-Russia Kaliningrad BMW GROUP BMW at AVTOTOR plant DAF TRUCKS NV BE-Belgium Westerlo DAF TRUCKS NV DAF NL-Netherlands Eindhoven DAF TRUCKS NV DAF UK-United Kingdom Leyland DAF TRUCKS NV DAF DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Affalterbach DAIMLER AG AMG DE-Germany Berlin DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Bremen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Dortmund DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz minibuses DE-Germany Düsseldorf DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Kölleda DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Ludwigsfelde DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, for VOLKSWAGEN DE-Germany Mannheim DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz (truck engines), Setra (JV KAMAZ) DE-Germany Neu-Ulm DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Rastatt DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Sindelfingen DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz DE-Germany Untertürkheim (Stuttgart) DAIMLER AG DE-Germany Wörth DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz, Unimog ES-Spain Samano DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz ES-Spain Vitoria DAIMLER AG Mercedes-Benz -

Corporate Governance in Ukraine / Not Gone with the Wind / May 2013

Ukraine| Research Corporate Governance Corporate Governance in Ukraine Not gone with the wind July 2013 Аlexander Paraschiy, Zenon Zawada, Roman Topolyuk, Roman Dmytrenko +380 44 391 5577 CONCORDE CAPITAL Corporate Governance in Ukraine July 2013 FOREWORD Companies not gone with the winds of change and hurricanes of crisis – upholding and preserving high standards of relations with investors and practices of corporate governance – are the foundation of our securities market, without exaggeration. And we’d like them to become the main heroes of our new story about corporate governance. Despite many disappointments in the history of the relatively young Ukrainian stock market, and in the history of our even younger study of corporate governance practices, they are there nevertheless. There are companies out there that are pleasant to work with for analysts and investors alike. There are companies that have stood the test of time and preserved the ability to be financed by capital markets. Despite noticing that high standards and practices are enforced mainly from without, and such standards are not always entirely grasped by the founders of Ukrainian business, we are satisfied that the number of companies striving to be better is increasing. It is increasing mainly owing to newcomers to the securities market: those who dared to take on the increasing requirements for Ukrainian issuers and those who are ready to adopt better practices in order to conform to international standards. We realize that a part of the newcomers (and newcomers, as our research shows, always behave themselves exemplarily) can loosen their high standards shown at their beginnings.