Thresholds: Jazz, Improvisation, Heterogeneity, and Politics in Postmodernity Michael David Székely

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Malcolm Braff's Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation

Malcolm Braff’s Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation: Definition, Analysis and Aesthetic Daniel Jacobus Steyn de Wet A dissertation submitted to the faculty of humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMUS. Johannesburg 2017 Plagiarism Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and to pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the author date convention for citation and referencing. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this thesis from the work or works of other people has been acknowledged through citation and reference. 3. The essay is my own work. 4. I have not allowed and will not allow anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. _______________________ _________________________ Signature Date Human Research Ethics Clearance (non-medical) Certificate Number: 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my friends and family for the support they have shown through this time. I further thank the various supervisors and co-supervisors who have at some point had some level of input into this study. On the practical side of my study I thank Malcolm Ney for the high level of classical training that I have received. I thank Andre Petersen for his input into the jazz specific aspects of my performance training. Special thanks to Dr. Carlo Mombelli for the training I received in his ensembles and at his home with regard to beautiful and improvised music. Thanks also go to the supervisors for the majority of my proposal phase Dr. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

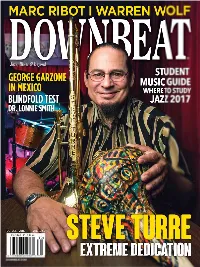

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Eartrip7.Pdf Download

CONTENTS Editorial An internet-related rant and a summary of the delights to follow in the rest of the current issue. By David Grundy. [pp.3-4] Listening to Sachiko M 12,000 words (count' em) – a lengthy, and no-doubt futile attempt to get to grips with some of the recordings of empty-sampler player (or, in her own words, 'non-musician'), Sachiko M, including interminable ramblings on such albums as 'Bar Sachiko,' 'Filament 1', and 'Tears'. By David Grundy. [pp.5-26] The Drop at the Foot of the Ladder: Musical Ends and Meanings of Performances I Haven't Been To, Fluxus and Today 11,000 words (count 'em), covering the delicate and indelicate negotiations between music and performance, audience and performer, art and non-art, that take place in the 1960s works of Fluxus and their distant inheritors, Mattin and Taku Unami. By Lutz Eitel. [pp.27-52] Feature: Live in Seattle Two solo takes and a duo relating to Coltrane's 1965 recording, made at the breaking point of his 'Classic Quartet', poised between old and new, music that pushes at the limits and drops back only to push again with furious persistence. By David Grundy and Sean Bonney. [pp.53-74] Interview: The Rent To call The Rent a Steve Lacy 'tribute band' would be to do them an immense disservice, though their repertoire consists mainly of Lacy compositions. Their conversation with Ted Harms covers such topics as inter-disciplinarity, the Lacy legacy, and the notion of jazz repertoire. [pp.75-83] You Tube Watch: Billy Harper A feature devoted this issue to the great Texan tenor Billy Harper. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Albert Ayler – Legendärer Und Umstrittenerer Free Jazzer

Jazz Collection: Albert Ayler – legendärer und umstrittenerer Free Jazzer Dienstag, 13. September 2016, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 17. September 2016, 22.35 - 24.00 Uhr (Erweiterungssendung) Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Annina Salis Es war eine kurze Karriere, die dem Saxophonisten Alber Ayler vergönnt war: 1962 stand er erstmals in einem Studio, 1970 wurde er leblos aus dem New Yorker East River gezogen. Dazwischen lagen rastlose acht Jahre, die bis heute nachhallen. Kein Exponent des Freejazz der 1960er-Jahre war so umstritten wie der Saxophonist Albert Ayler. Für die einen hatte seine Musik nichts mit Jazz zu tun, für die anderen war er der Verkünder eines neuen Zeitalters. Ein musikalischer Prediger war er in jedem Fall: Mit hymnischem Gestus, obertonreichem und expressivem Klang und frei fliessendem Rhythmus schrie er seine Botschaft in die Welt. «We play peace!», betonte er immer wieder, - wie das zu hören ist, diskutiert Annina Salis mit der deutschen Saxophonistin Silke Eberhard. Albert Ayler: My Name Is Albert Ayler Label: Debut Track 01: Introduction by Albert Ayler Track 03: Billie’s Bounce Albert Ayler: Spiritual Unity Label: ESP Track 01: Ghosts (First Variation) Albert Ayler: In Greenwich Village Label: Impulse Track 01: Truth Is Marching In Albert Ayler: Love Cry Label: Impulse Track 02: Love Cry Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost Label: Revenant Track VI/1: Thank God for Women Albert Ayler: Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe Label: Impulse Track 01: Music Is The Healing Albert Ayler: Nuits de la Fondation Maeght 1970 Label: Albert Ayler Estate Track 01: In Heart Only Bonustracks – nur in der Samstagsausgabe Albert Ayler: Meditations Label: Impulse! Track 01: The Father And the Son And the Holy Ghost Archie Shepp – Live In San Francisco Label: Impulse! Track 01: Keep Your Heart Right Track 02: Lady Sings The Blues Don Cherry – Complete Communion Label: Blue Note Track 01: Complete Communion . -

Music Guide 13 the Beat 180 Master Class by ELDAR DJANGIROV 194 Blindfold Test Where to Study Jazz 2017 24 Players 182 Pro Session Dr

October 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 10 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Solos & Duos Series Announces Its 2Nd Season

www.resarts.com/solosandduos Contact: Glenn Siegel, 413-545-2876 Solos & Duos Series announces its 2nd season: Milford Graves, Sunny Murray Duo w/Sabir Mateen and Sonny Fortune/Rashied Ali Duo The UMass Fine Arts Center’s Solos & Duos Series will bring together three giants of the percussive arts for its 2nd season, with concerts by Milford Graves (September 25) the Sunny Murray Duo featuring Sabir Mateen (October 9) and the Sonny Fortune/Rashied Ali Duo (November 20). All concerts begin at 8:00 pm., in Bezanson Recital Hall, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Tickets are $10 and $5 (students), and are available through the Fine Arts Center box office, 545-2511 or 1-800- 999-UMAS. Three men expanded the jazz drum vocabulary during the 1960s: Milford Graves, Sunny Murray and Rashied Ali. It is an honor and privilege to be able to present these three masters in one season. A drummer of unparalleled power and creativity, Milford Graves is a living legend. Professor, herbalist, healer, Milford Graves is first and foremost one of the world's great geniuses of the drum. Rarely heard live, a concert by Milford Graves is a special event. Born in 1941, in Jamaica, New York, Milford Graves made his first recordings on the ESP label with the New York Art Quartet (with John Tchicai, Archie Shepp and Lewis Worrell), pianists Lowell Davidson and Paul Bley. Graves was a founding member of the Jazz Composer's Orchestra and has subsequently worked and recorded with a wide variety of creative musicians including Albert Ayler, Sonny Sharrock, Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Don Pullen and Andrew Cyrille. -

18. the Far-Ranging 19605

18. The Far-Ranging 19605 n the 1960s, rock ' n roll sought to create jazz that had and Motown were more to say. I monopolizing popular He was a world leader in music. The big jazz bands of the free jazz movement ofthe the 1930s and '40s and the 1960s, but Ayler's early singers of the '50s had faded influences offered little or no from the public consciousness. indication of his eventual It was a critical time for jazz. experiments in unstructured Jazz had not been the world's music. most popular music for almost Born in Cleveland July 13, two decades and seemed to be 1936, Ayler was raised by almost lost in the cross-fire of Edward and Myrtle Ayler in other forms of musical Shaker Heights. He grew up entertainment. in a very musical atmosphere. Some artists, who viewed Cleveland Press I CSU Archives He said his father played jazz as an almost straight-line Albert Ayler violin and a Dexter Gordon- evolutionary process, tried to style saxophone. "When I extend it in a variety of directions, sometimes with was two," recalled Albert, "I used to blow foot stool. disastrous results. Others, rejecting the need to expand, My mother told me I'd hold it up to my mouth and blow reverted to earlier styles of jazz. The result was a as if it were a horn." When his father played Lionel fragmentation of jazz which, in turn, diminished its Hampton records, Albert would mimic the musicians. general popularity. Jazz had moved from the Edward decided to teach his son to play alto sax.