The Improvisational Language of Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philip Catherine

PHILIP CATHERINE Sinds de jaren '60 is Philip Catherine één van de vooraanstaande figuren van de Europese jazzscène. Zijn samenwerking met jazzgrootheden zoals Chet Baker, Tom Harrell, NHOP, Stéphane Grappelli, Larry Coryell, Dexter Gordon, Charles Mingus, zijn unieke stijl en klankkleur alsook zijn ongebreidelde inzet voor de muziek zijn van een niet te miskennen invloed geweest op de ontwikkeling van de Europese jazz. Hij is net 18 jaar oud wanneer hij met het Lou Bennett trio op tournee door Europa trekt. In 1971 wordt hij door Jean-Luc Ponty gevraagd om mee te spelen in diens kwintet. Dat jaar verschijnt ook de eerste plaat onder zijn naam ‘Stream ’, gevolgd door de albums " September Man " en " Guitars " in 1974-75. Jazzliefhebbers uit de hele wereld ontdekken een nieuwe ster aan het jazzfirmament: een jonge, virtuoze gitarist die ook een begenadigd componist blijkt te zijn. Thema’s als ‘Homecomings’ en ‘Nairam’ zijn ondertussen beroemd geworden. Philip Catherine heeft meer dan 20 platen uitgebracht onder zijn naam en tevens talrijke opnames met artiesten van alle horizonten, van Chet Baker via Dexter Gordon tot de cultband Focus. De plaat ‘ Transparence ’ uit ’86 werd een bestseller en is tegelijk ook één van Philip’s uitverkoren opnames. Daarop volgen begin jaren ’90 twee schitterende cd’s met trompettist Tom Harrell : Moods Vol.I en II . In ’97 tekent Philip Catherine bij het jazzlabel Dreyfus Records. Zijn eerste cd voor dit platenlabel, “ Philip Catherine- Live ” is meteen ook het eerste live-album uit zijn discografie. De jazzkritiek is uiterst enthusiast. De Cd krijgt o.m. een 4 ½ ster-vermelding in “Down Beat” in de V.S. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

L'émergence D'un Nouveau Faire Musical En France

L’émergence d’un nouveau faire musical en France dans les années 1960 Marc Kaiser To cite this version: Marc Kaiser. L’émergence d’un nouveau faire musical en France dans les années 1960. 2020. hal- 02554418 HAL Id: hal-02554418 https://hal-univ-paris8.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02554418 Preprint submitted on 20 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MARC KAISER L’EMERGENCE D’UN NOUVEAU FAIRE MUSICAL EN FRANCE DANS LES ANNEES 1960 Pour appréhender l’essor d’un « faire rock » dans les années 1960 en France, en tant que processus créatif ayant émergé autour de nouvelles dynamiques et associations, nous nous appuyons sur le fonds d’archives du Centre d’Information et de Documentation du Disque (C.I.D.D.) auquel nous avons eu accès à la B.N.F. Nous avons pu exploiter, dans le cadre d’un contrat de chercheur associé, 5 mètres linéaires d’archives répartis en 12 cartons (qui contiennent notamment des correspondances, des études, des rapports, des pièces comptables et des coupures de presse). Dans le cadre de cet article, nous nous attachons à révéler dans quelle mesure les premières formes de rock français ont été inscrites dans des processus de production éprouvés pour les musiques de variétés. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Undercurrent (Blue Note)

Kenny Drew Undercurrent (Blue Note) Undercurrent Freddie Hubbard, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor sax; Kenny Drew, piano; Sam Jones, bass; Louis Hayes, drums. 1. Undercurrent (Kenny Drew) 7:16 Produced by ALFRED LION 2. Funk-Cosity (Kenny Drew) 8:25 Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF 3. Lion's Den (Kenny Drew) 4:53 Cover Design by REID MILES 4. The Pot's On (Kenny Drew) 6:05 Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER 5. Groovin' The Blues (Kenny Drew) 6:19 Recorded on December 11, 1960, 6. Ballade (Kenny Drew) 5:29 Englewood Cliffs, NJ. The quintet that plays Kenny Drew's music here had never worked as a unit before the recording but the tremendous cohesion and spirit far outdistances many of today's permanent groups in the same genre. Of course, Sam Jones and Louis Hayes have been section mates in Cannonball Adderley's quintet since 1959 and this explains their hand-in- glove performance. With Drew, they combine to form a rhythm trio of unwavering beat and great strength. The two hornmen are on an inspired level throughout. Hank Mobley has developed into one of our most individual and compelling tenor saxophonists. His sound, big and virile, seems to assert his new confidence with every note. Mobley has crystallized his own style, mixing continuity of ideas, a fine sense of time and passion into a totality that grabs the listener and holds him from the opening phrase. Freddie Hubbard is a youngster but his accomplished playing makes it impossible to judge him solely from the standpoint of newcomer. This is not to say that he is not going to grow even further as a musician but that he has already reached a level of performance that takes some cats five more years to reach. -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

Comes to Life in ELLA, a Highly-Acclaimed Musical Starring Tina Fabrique Limited Engagement

February 23, 2011 Jazz’s “First Lady of Song” comes to life in ELLA, a highly-acclaimed musical starring Tina Fabrique Limited engagement – March 22 – 27, 2011 Show features two dozen of the famed songstresses’ greatest hits (Philadelphia, February 23, 2011) — Celebrate the “First Lady of Song” Ella Fitzgerald when ELLA, the highly-acclaimed musical about legendary singer Ella Fitzgerald, comes to Philadelphia for a limited engagement, March 22-27, 2011, at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Featuring more than two-dozen hit songs, ELLA combines myth, memory and music into a stylish and sophisticated journey through the life of one of the greatest jazz singers of the 20th century. Broadway veteran Tina Fabrique, under the direction of Rob Ruggiero (Broadway: Looped starring Valerie Harper, upcoming High starring Kathleen Turner), captures the spirit and exuberance of the famed singer, performing such memorable tunes as “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” “That Old Black Magic,” “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” and “It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” ELLA marks the first time the Annenberg Center has presented a musical as part of its theatre series. Said Annenberg Center Managing Director Michael J. Rose, “ELLA will speak to a wide variety of audiences including Fitzgerald loyalists, musical theatre enthusiasts and jazz novices. We are pleased to have the opportunity to present this truly unique production featuring the incredible vocals of Tina Fabrique to Philadelphia audiences.” Performances of ELLA take place on Tuesday, March 22 at 7:30 PM; Thursday, March 24 at 7:30 PM; Friday, March 25 at 8:00 PM; Saturday, March 26 at 2:00 PM & 8:00 PM; and Sunday, March 27 at 2:00 PM. -

Skain's Domain – Episode 5

Skain's Domain – Episode 5 Skain's Domain Episode 5 - April 20, 2020 0:00:01 Moderator: Wynton, you're ready? 0:00:02 Wynton Marsalis: I'm ready. 0:00:03 Moderator: Alright. 0:00:06 WM: I wanna thank all of you for joining me once again. This is Skain's Domain, we're talking about subjects significant and trivial, with the same intensity and feeling. We're gonna talk tonight... I'm gonna start off by talking about a series we're gonna start, which is, "How to develop your ability to hear, listen to music." I think that for many years, me and a great seer of the American vernacular, Phil Schaap, argued about the importance of music appreciation. We tend to spend a lot of time with musicians, talking about music, and we forget about the general audience of listeners, so I'm gonna go through 16 steps of hearing, over the time. I'm gonna be announcing when it is, and I'm just gonna talk about the levels of hearing from when you first start hearing music, to as you deepen your understanding of music, and you're able to understand more and more things, till I get to a very, very high level of hearing. Some of it comes from things that we all know from studying music and even what we like, what we listen to, but also it comes from the many different experiences I've had with great musicians, from the beginning. I can always remember hearing when I was a kid, the story of Ben Webster, the great balladeer on tenor saxophone. -

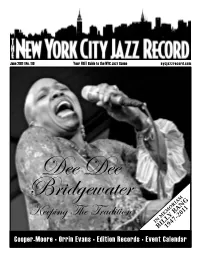

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Kenny Drew Trio Morning Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kenny Drew Trio Morning mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Morning Country: Netherlands Released: 1976 Style: Post Bop, Modal MP3 version RAR size: 1973 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1669 mb WMA version RAR size: 1258 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 769 Other Formats: AA MP4 MP3 MP1 MP2 MMF MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Evening In The Park A1 Written-By – K. Drew* Autumn Leaves A2 Written-By – Kosma* Morning B1 Written By – P. Carsten Isn't Romantic B2 Written-By – Hart*, Rodgers* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Rosenberg Studio Credits Bass – Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen Guitar – Philip Catherine Piano – Kenny Drew Notes Recorded at Rosenberg Studio on September 8, 1975 Cover identical to Danish release label reads 'Made in Holland'. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SCS-1048 Kenny Drew Trio* Morning (LP, Album) SteepleChase SCS-1048 Denmark 1976 RJ-7123 Kenny Drew Trio* Morning (LP, Album) SteepleChase RJ-7123 Japan 1976 SCS-1048 Kenny Drew Trio* Morning (LP, Album) SteepleChase SCS-1048 Denmark 1976 IC 2048 Kenny Drew Trio* Morning (LP, Album) Inner City Records IC 2048 US 1976 Related Music albums to Morning by Kenny Drew Trio Jackie McLean / Dexter Gordon - The Source Dexter Gordon Quartet - The Apartment Kenny Drew Jr. - Kenny Drew, Jr. The Kenny Drew Trio - Dark Beauty Sonny Rollins With The Modern Jazz Quartet Featuring Art Blakey And Kenny Drew - Sonny Rollins With The Modern Jazz Quartet Kim Parker And The Kenny Drew Trio - "Havin' Myself A Time" The Kenny Drew Trio - New Faces – New Sounds, Introducing The Kenny Drew Trio Kenny Drew Trio - Dark Beauty Tete Montoliu Trio - Tete! Harry "Sweets" Edison & Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis With Kenny Drew & John Darvilles Quartet - In Copenhagen. -

Spilleliste: Åtti Deilige År Med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14

Spilleliste: Åtti deilige år med Blue Note Foredrag Oslo Jazz Circle, 14. januar 2020 av Johan Hauknes Preludium BLP 1515/16 Jutta Hipp At The Hickory House /1956 Hickory House, NYC, April 5, 1956 Jutta Hipp, piano / Peter Ind, bass / Ed Thigpen, drums Volume 1: Take Me In Your Arms / Dear Old Stockholm / Billie's Bounce / I'll Remember April / Lady Bird / Mad About The Boy / Ain't Misbehavin' / These Foolish Things / Jeepers Creepers / The Moon Was Yellow Del I Forhistorien Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons & Pete Johnson Jumpin' Blues From Spiritals to Swing, Carnegie Hall, NYC, December 23, 1938 BN 4 Albert Ammons - Chicago In Mind / Meade "Lux" Lewis, Albert Ammons - Two And Fews Albert Ammons Chicago in Mind probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, January 6, 1939 BN 6 Port of Harlem Seven - Pounding Heart Blues / Sidney Bechet - Summertime 1939 Sidney Bechet, soprano sax; Meade "Lux" Lewis, piano; Teddy Bunn, guitar; Johnny Williams, bass; Sidney Catlett, drums Summertime probably WMGM Radio Station, NYC, June 8, 1939 Del II 1500-serien BLP 1517 Patterns in Jazz /1956 Gil Mellé, baritone sax; Eddie Bert [Edward Bertolatus], trombone; Joe Cinderella, guitar; Oscar Pettiford, bass; Ed Thigpen, drums The Set Break Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, April 1, 1956 BLP 1521/22 Art Blakey Quintet: A Night at Birdland Clifford Brown, trumpet; Lou Donaldson, alto sax; Horace Silver, piano; Curly Russell, bass; Art Blakey, drums A Night in Tunisia (Dizzy Gillespie) Birdland, NYC, February 21, 1954 BLP 1523 Introducing Kenny Burrell /1956 Tommy Flanagan, -

CELEBRATING OSCAR PETERSON Posted on February 16, 2021

BLACK HISTORY MONTH | CELEBRATING OSCAR PETERSON Posted on February 16, 2021 Category: News Oscar Emmanuel Peterson (1925–2007) | Agent of Change | Remembered as a virtuoso jazz pianist and composer of Hymn to Freedom, an international anthem to civil rights. The son of immigrants from the West Indies, Oscar Peterson was born in Montréal, Québec and grew up in Little Burgundy, a predominantly Black neighbourhood of the city where he was immersed in the culture of jazz. He was five years old when he began taking music lessons from his father. He also studied classical piano with his sister, Daisy Peterson Sweeney, who went on to teach other renowned jazz artists. Peterson later attended the Conservatoire de musique du Québec è Montrèal and studied classical piano with Paul de Marky, but with a deep interest in jazz, he also played boogie-woogie and ragtime. At only 14 years old, Peterson won the national Canadian Broadcasting Corporation music competition, after which he dropped out of high school and joined a band with jazz trumpeter and classmate Maynard Ferguson. While still a teenager, Peterson played professionally at hotels and at a weekly radio show. He also joined the Jonny Holmes Orchestra as its only Black musician. From 1945 to 1949, Peterson recorded 32 songs with RCA Victor. Beginning in the 1950s, he released several albums each year while appearing on over 200 albums by other artists including Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dizzy Gillespie. In 1949, jazz impresario Norman Ganz was on his way to the airport in Montréal, when hearing Peterson playing live on radio, asked the cab driver to take him to the club where the concert was being aired.