The Evolving Role of the Solo Euphonium in Orchestral Music: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Sheku Kanneh-Mason

Sheku Kanneh-Mason Sheku Kanneh-Mason is the 2016 BBC Young Musician, a title he won with a stunning performance of the Shostakovich Cello Concerto at London’s Barbican Hall with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. In April 2017, Sheku returned to the hall for another performance of the concerto, this time with the National Youth Orchestra and Carlos Miguel Prieto after which the Guardian wrote that “technically superb and eloquent in his expressivity, he held the capacity audience spellbound with an interpretation of exceptional authority” and the Telegraph acknowledged “what a remarkable musician he already is, bringing other- worldly tone to the haunting slow movement and displaying mature musicianship in his handling of the extended cadenza” Only eighteen years old, Sheku’s international career is developing very quickly with engagements in the 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons including the CBSO, the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Newbury Spring Festival, a return to the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, Barcelona Symphony, Netherlands Chamber Orchestra (his debut at the Concertgebouw), Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (Sheku’s concerto debut in North America), Louisiana Philharmonic, and the Seattle and Atlanta symphonies. He will also return to the BBC Symphony Orchestra to perform the Elgar Concerto in his hometown of Nottingham and make his debut at the Vienna Konzerthaus with the Japan Philharmonic. In recital, Sheku has several concerts across the UK with highlights over the next two seasons including his debuts at Kings Place as part of their Cello Unwrapped series, Milton Court, and Wigmore Hall. He will also perform a series of concerts in Canada in December 2017, and further recitals at the Zurich Tonhalle, and the Lucerne Festival. -

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène DU 15 AU 28 OCTOBRE 2013 6 REPRESENTATIONS Théâtre des Champs-Elysées SERVICE DE PRESSE +33 1 49 52 50 70 theatrechampselysees.fr La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la RESERVATIONS programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. +33 1 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr Spontini 5 La Vestale La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène Emmanuel Clolus décors Marguerite Bordat costumes Philippe Berthomé lumières Daria Lippi dramaturgie Ermonela Jaho Julia Andrew Richards Licinius Béatrice Uria-Monzon La Grande Vestale Jean-François Borras Cinna Konstantin Gorny Le Souverain Pontife Le Cercle de l’Harmonie Chœur Aedes 160 ans après sa dernière représentation à Paris, le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées présente une nouvelle production de La Vestale de Gaspare Spontini. Spectacle en français Durée de l’ouvrage 2h10 environ Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Théâtre de la Monnaie, Bruxelles MARDI 15, VENDREDI 18, MERCREDI 23, VENDREDI 25, LUNDI 28 OCTOBRE 2013 19 HEURES 30 DIMANCHE 20 OCTOBRE 2013 17 HEURES SERVICE DE PRESSE Aude Haller-Bismuth +33 1 49 52 50 70 / +33 6 48 37 00 93 [email protected] www.theatrechampselysees.fr/presse Spontini 6 Dossier de presse - La Vestale 7 La Vestale La nouvelle production du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées La Vestale n’a pas été représentée à Paris en version scénique depuis 1854. On doit donner encore La Vestale... que je l’entende une seconde fois !... Quelle Le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées a choisi, pour cette nouvelle production, de œuvre ! comme l’amour y est peint !.. -

Nicola Benedetti Interview: ‘It’S Hard When You Feel You’Re Doing Your Part, but Others Aren’T Doing Theirs’

Nicola Benedetti interview: ‘It’s hard when you feel you’re doing your part, but others aren’t doing theirs’ As she launches her new album, the star violinist is frustrated at the restrictions on live performance, but is determined to bring music to the masses regardless Nicola Benedetti at Royal Albert Hall - 21 September 2013 – by Allan Beavis by Jessica Duchen 15/07/2021 Some people quit when faced with lockdown. Others don’t. When the pandemic abruptly smothered live music, the violinist Nicola Benedetti threw her considerable energy into finding new ways to connect people online to music and, through that, to one another. Now the Scottish star soloist is preparing for a Prom, where she will perform Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain and, at last, a real, live audience. That should make the thrill for the NYOGB youngsters in the Royal Albert Hall even greater. “After a year and a half, with so much cancelled and no opportunity to get together, can you imagine how excited they’re going to be?” Benedetti enthuses. To say that musicians have felt frustrated and dispirited these past months is not saying enough. This summer, sports began to be allowed massive audiences, while theatres and concert halls were hobbled by continued social distancing. Benedetti does not mince her words: “It’s difficult when you see the football with 40,000 to 60,000 people gathering just in official numbers in official venues, never mind millions in the streets, and you look at musicians’ restrictions in that context. -

Recital Report

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1975 Recital Report Robert Steven Call Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Call, Robert Steven, "Recital Report" (1975). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 556. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/556 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECITAL REPORT by Robert Steven Call Report of a recital performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OP MUSIC in ~IUSIC UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1975 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to expr ess appreciation to my private music teachers, Dr. Alvin Wardle, Professor Glen Fifield, and Mr. Earl Swenson, who through the past twelve years have helped me enormously in developing my musicianship. For professional encouragement and inspiration I would like to thank Dr. Max F. Dalby, Dr. Dean Madsen, and John Talcott. For considerable time and effort spent in preparation of this recital, thanks go to Jay Mauchley, my accompanist. To Elizabeth, my wife, I extend my gratitude for musical suggestions, understanding, and support. I wish to express appreciation to Pam Spencer for the preparation of illustrations and to John Talcott for preparation of musical examp l es. iii UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1972 - 73 Graduate Recital R. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

Amaryllis Fleming Concert Hall Maxim Vengerov Conductor Roberto Ruisi Violin Maria Gîlicel Violin Line Faber Violin RCM Symphony Orchestra

ORCHESTRAL MASTERCLASS WITH MAXIM VENGEROV Thursday 28 June 2018 7pm | Amaryllis Fleming Concert Hall Maxim Vengerov conductor Roberto Ruisi violin Maria Gîlicel violin Line Faber violin RCM Symphony Orchestra ORCHESTRAL MASTERCLASS WITH MAXIM VENGEROV Thursday 28 June 2018, 7pm | Amaryllis Fleming Concert Hall Maxim Vengerov conductor Roberto Ruisi violin (movement i) Maria Gîlicel violin (movement ii) Line Faber violin (movement iii) RCM Symphony Orchestra Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major op 61 (1770–1827) i Allegro ma non troppo INTERVAL ii Larghetto iii Rondo. Allegro RCM Polonsky Visiting Professor of Violin Maxim Vengerov returns to the College for another highly anticipated masterclass. One of the greats of the repertoire, RCM violinists and the RCM Symphony Orchestra explore Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. This masterclass will be live streamed to www.rcm.ac.uk/live. Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major op 61 Although Beethoven completed only one concerto for violin, he certainly began work on another. All that survives of the earlier attempt is the opening section of a first movement in C major, but the condition of manuscript is such that it is entirely possible that the rest once existed, but has since been lost. The fragment probably dates from the early 1790s and reveals a confident treatment of the soloist, and a penchant for the upper reaches of the instrument’s range that anticipates one of the notable features of the masterpiece that was to follow more than a decade later. The exact circumstances of the D major Concerto’s commissioning are not known, but it was evidently written for Franz Clement, a very distinguished Viennese conductor (notably at the Theater an der Wien) and violinist. -

Hoover Beginning Band

Hoover Beginning Band Welcome, musicians! All students are welcome to join band without experience ! Beginning Band is a year-long elective that meets every day during school. Band does require home practice and instrument rental. Simply request “Beginning Band (Band 1)” on your schedule request form. ● Want to get a head start on learning an instrument? ○ Register for summer band! (June TBD). Applications can be picked up in the HMS front office or from your elementary music teacher after Spring Break. ● NO EXPERIENCE REQUIRED! ○ If you have never played an instrument before, don’t worry! Everyone is welcome in beginning band! ● Are you already in Orchestra? ○ You can continue into the Hoover Intermediate Orchestra AND take Beginning Band! ● Do we have grades in band? ○ Yes, just like any elective class that meets daily. Band students are graded on their rehearsal etiquette, performance attendance, and individual playing tests. ● Required Evening Performances: ○ Fall Informance : October ○ Winter Concert: December ○ Spring Concert : May ● Additional Performance Opportunities: ○ Solo & Ensemble : February/May ● Instrument Options: (students try each instrument and are placed on the best fit by Ms. Leffard) ○ Woodwinds: Flute, Clarinet, Alto Saxophone, Oboe, Bassoon ○ Brass : Trumpet, French Horn, Trombone, Euphonium, Tuba ○ Percussion : Audition only (no previous experience required) ● Instrument Rentals: ○ Instruments rented from Hoover include : Tuba, Euphonium, French Horn, and Percussion ○ Instruments rented from The Horn Section include : Flute, Clarinet, Alto Saxophone, Trumpet, and Trombone ○ If you are concerned about the cost of renting an instrument, please contact Ms. Leffard. ● Do you already play a band instrument? If you have experience on one of the instruments listed above, please contact Ms. -

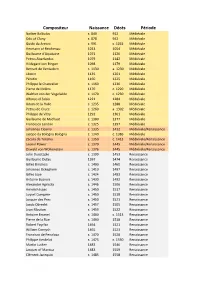

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

The Legacy of Aaron Copland Reference Materials: General Performance Tips and Techniques

The Legacy of Aaron Copland Reference Materials: General Performance Tips and Techniques INTRODUCTION The United States Army Field Band and Soldiers’ Chorus have recently completed an ambitious recording project to celebrate the centenary of the “Dean of American Music,” Aaron Copland. With the 100th anniversary of his birth on November 14, 2000, ensembles throughout the nation and around the world are programming Copland’s music now more than ever. Our Legacy of Aaron Copland reference recordings and our online resources are intended to make his music more accessible to students and to assist conductors and educators in preparing for their own performances. During our recording sessions and the rehearsals that led up to them, the members of the Field Band learned much about Aaron Copland and his music. We have chosen to share some of those insights through An Educator’s Guide to the Music of Aaron Copland. JUDICIOUS EDITING One of the first lessons any performer learns is that the printed music is only a guide to the sounds which the composer wishes to have recreated. Students should realize that professional musicians use their experience to judiciously edit printed parts; this makes things easier to play, or better reflects the composer’s original intent. Seemingly small changes can often result in much cleaner execution of parts. They can also reduce the technical requirements for most of the sections, while maintaining the rhythmic pulse. Educators can greatly improve the performance of their ensembles by judicious editing, allowing their strongest players to carry the load, while easing the burden for less-experienced students.