British Troops, Colonists, Indians, and Slaves in Southeastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2017 Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves Beau Duke Carroll University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Carroll, Beau Duke, "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Beau Duke Carroll entitled "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Jan Simek, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David G. Anderson, Julie L. Reed Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Beau Duke Carroll December 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Beau Duke Carroll All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the following people who contributed their time and expertise. -

The Indian Trade War Reconsidered: Morris on Ivers

Larry E. Ivers. This Torrent of Indians: War on the Southern Frontier, 1715-1728. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016. 292 pp. $24.95, paper, ISBN 978-1-61117-606-3. Reviewed by Michael Morris Published on H-SC (September, 2016) Commissioned by David W. Dangerfield (University of South Carolina - Salkehatchie) If South Carolina’s Yamasee War is ever given tribes and forgotten forts. His secondary works a subtitle, it could rightly be called the Great Indi‐ run the gamut from Verner Crane's 1959 classic, an Trade War. Larry Ivers, a lawyer by training The Southern Frontier to William Ramsey's 2008 with a military background, notes in his preface work, The Yamasee War. that his intent was to fll a void in the history of The frst three chapters set the stage for con‐ the Yamasee War and to provide a more detailed flict by discussing the Indian agents and traders analysis of the military operations of the war. To who caused the crisis by enslavement of debtor that end, he clearly succeeds in recreating the sto‐ Indians, and one of its strengths is naming people ry of a colony at war aggravated by professional who are otherwise shadowy fgures in backcoun‐ Indian traders who trafficked in Indian slaves to try history. The Yamasee leadership clearly pay their debts. Ivers reveals an incredibly de‐ warned traders Samuel Warner and William Bray tailed account of the debacle and this detailed of a planned murder of all traders and an attack analysis is both a major strength and a minor on the colony if the South Carolina government weakness of the work. -

A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine Andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation White, andrea Paige, "Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626354. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-whwd-r651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIVING ON THE PERIPHERY: A STUDY OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY YAMASEE MISSION COMMUNITY IN COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Andrea P. White 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of aster of Arts Author Approved, November 2002 n / i i WJ m Norman Barka Carl Halbirt City Archaeologist, St. Augustine, FL Theodore Reinhart TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 2 Creolization Models in Historical Archaeology 4 Previous Archaeological Work on the Yamasee and Significance of La Punta 7 PROJECT METHODS 10 Historical Sources 10 Research Design and The City of St. -

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1. The system of indentured labor used during the Colonial period had which of the following effects? A. It enabled England to deport most criminals. B. It enabled poor people to seek opportunity in America. C. It delayed the establishment of slavery in the South until about 1750. D. It facilitated the cultivation of cotton in the South. E. It instituted social equality. 2. Indentured servants were usually A. slaves who had been emancipated by their masters B. free blacks forced to sell themselves into slavery by economic conditions. C. paroled prisoners bound to a lifetime of service in the colonies D. persons who voluntarily bound themselves to labor for a set number of years in return for transportation in the colonies. E. the sons and daughters of slaves. 3. The headright system adopted in the Virginia colony A. determined the eligibility of a settler for voting and holding office. B. toughened the laws applying to indentured servants. C. gave 50 acres of land to anyone who would transport himself to the colony. D. encouraged the development of urban centers. E. prohibited the settlement of single men and women in the colony. 4. Of the African slaves brought to the New World by Europeans from 1492 through 1770, the vast majority were shipped to A Virginia B the Carolinas C the Caribbean D Georgia E Florida 5. A majority of the early English migrants to the Chesapeake were A. Families with young children B. Indentured servants C. Wealthy gentlemen D. Merchants and craftsmen E. -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

A Thirtieth Anniversary Gathering in Memory of the Little Tennessee

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 1-1-2010 Setting It Straight: A Thirtieth Anniversary Gathering in Memory of the Little eT nnessee River and its Valley Zygmunt J.B. Plater Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Land Use Planning Commons Recommended Citation Zygmunt J.B. Plater, Setting It Straight: A Thirtieth Anniversary Gathering…in Memory of the Little Tennessee River and its Valley. Newton, MA: Z. Plater, 2010. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SSSeeettttttiiinnnggg IIIttt SSStttrrraaaiiiggghhhttt::: aaa TTThhhiiirrrtttiiieeettthhh AAAnnnnnniiivvveeerrrsssaaarrryyy GGGaaattthhheeerrriiinnnggg ......... iiinnn MMMeeemmmooorrryyy ooofff ttthhheee LLLiiittttttllleee TTTeeennnnnneeesssssseeeeee RRRiiivvveeerrr aaannnddd IIItttsss VVVaaalllllleeeyyy Created: 200,000,000 BC — eliminated by TVA: November 29, 1979 R.I.P. AAA RRReeeuuunnniiiooonnn ooofff TTTeeelllllliiicccooo DDDaaammm RRReeesssiiisssttteeerrrss::: fffaaarrrmmmeeerrrsss &&& lllaaannndddooowwwnnneeerrrsss,,, ssspppooorrrtttsssmmmeeennn,,, ttthhheee EEEaaasssttteeerrrnnn BBBaaannnddd ooofff CCChhheeerrroookkkeeeeeesss,,, &&& cccooonnnssseeerrrvvvaaatttiiiooonnniiissstttsss Vonore Community Center, Vonore, Tennessee, November 14, 2009 The Little Tennessee River: A Time-Line 200,000,000 BC — God raises up the Great Smoky Mountains, and the Little T starts flowing westward down out of the mountains. 8000 BC — archaic settlements arise in the meadows along the Little T in the rolling countryside West of the mountains. 1000-1400 AD — Early proto-Cherokee Pisgah culture; villages are scattered along the Little T. -

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Hosts Keetoowah Cherokee Language Classes Throughout the Tribal Jurisdictional Area on an Ongoing Basis

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: United Keetoowah (ki-tu’-wa ) Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Tribal website(s): www.keetoowahcherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” Original Homeland Archeologists say that Keetoowah/Cherokee families began migrating to a new home in Arkansas by the late 1790's. A Cherokee delegation requested the President divide the upper towns, whose people wanted to establish a regular government, from the lower towns who wanted to continue living traditionally. On January 9, 1809, the President of the United States allowed the lower towns to send an exploring party to find suitable lands on the Arkansas and White Rivers. Seven of the most trusted men explored locations both in what is now Western Arkansas and also Northeastern Oklahoma. The people of the lower towns desired to remove across the Mississippi to this area, onto vacant lands within the United States so that they might continue the traditional Cherokee life. -

By Robert A. Jockers D.D.S

By Robert A. Jockers D.D.S. erhaps the most significant factor in the settlement of identify the original settlers, where they came from, and Western Pennsylvania was an intangible energy known as specifically when and where they settled. In doing so it was the "Westward Movement.' The intertwined desires for necessary to detail the complexity of the settlement process, as well economic, political, and religious freedoms created a powerful as the political, economic, and social environment that existed sociological force that stimulated the formation of new and ever- during that time frame. changing frontiers. Despite the dynamics of this force, the In spite of the fact that Moon Township was not incorporated settlement of "Old Moon Township" - for this article meaning as a governmental entity within Allegheny County, Pa., until 1788, contemporary Moon Township and Coraopolis Borough - was numerous events of historical significance occurred during the neither an orderly nor a continuous process. Due in part to the initial settlement period and in the years prior to its incorporation. area's remote location on the English frontier, settlement was "Old Moon Township" included the settlement of the 66 original delayed. Political and legal controversy clouded the ownership of land grants that comprise today's Moon Township and the four its land. Transient squatters and land speculators impeded its that make up Coraopolis. This is a specific case study but is also a growth, and hostile Indian incursions during the American primer on the research of regional settlement patterns. Revolution brought about its demise. Of course, these lands were being contested in the 1770s. -

A Spatial and Elemental Analyses of the Ceramic Assemblage at Mialoquo (40Mr3), an Overhill Cherokee Town in Monroe County, Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2019 COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE Christian Allen University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Allen, Christian, "COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5572 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christian Allen entitled "COALESCED CHEROKEE COMMUNITIES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPATIAL AND ELEMENTAL ANALYSES OF THE CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE AT MIALOQUO (40MR3), AN OVERHILL CHEROKEE TOWN IN MONROE COUNTY, TENNESSEE." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Kandace Hollenbach, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Gerald Schroedl, Julie Reed Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. -

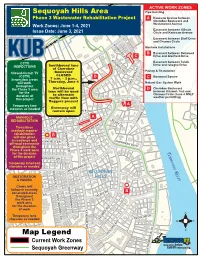

Sequoyah Hills Area Map Legend

NORTH BELLEMEADE AVE ACTIVE WORK ZONES Sequoyah Hills Area Pipe-bursting Phase 3 Wastewater Rehabilitation Project A Kenesaw Avenue between Cherokee Boulevard and Work Zones: June 1-4, 2021 Westerwood Avenue Easement between Hillvale Issue Date: June 3, 2021 KINGSTON PIKE Circle and Kenesaw Avenue Easement between Bluff Drive and Cheowa Circle BOXWOOD SQ Manhole Installations B Easement between Dellwood C Drive and Glenfield Drive KITUWAH TRL CCTV Easement between Talahi Southbound lane Drive and Iskagna Drive INSPECTIONS EAST HILLVALE TURN of Cherokee Paving & Restoration Closed-Circuit TV BoulevardWEST HILLVALE TURN CLOSED (CCTV) D C Boxwood Square Inspection crews 7 a.m. – 3 p.m., will work Thursday, June 4 Natural Gas System Work throughout LAKE VIEW DR the Phase 3 area Northbound D Cherokee Boulevard for the lane will be used between Kituwah Trail and to alternate Cheowa Circle (June 4 ONLY duration of weather permitting) this project traffic flow with flaggers present Temporary lane A closures as needed WOODHILLGreenway PL will remain openHILLVALE CIR MANHOLE A BLUFF DR REHABILITATION CHEOWA CIR Trenchless DELLWOOD DR manhole repairs/ OAKHURST DR KENESAW AVE TOWANDArehabilitation TRL B will take place in roadwaysSCENIC DR and GLENFIELD DR CHEROKEE BLVD off-road easements throughout the Phase 3 work zone Tennessee River for the duration of this project KENILWORTH DR Temporary lane/road closures as needed ALTA VISTA WAY WINDGATE ST ISKAGNA DR WOODLAND DR SEQUOYAH RESTORATION HILLS & PAVING Crews will EAST NOKOMIS CIR follow in recently B excavated areas WEST NOKOMIS CIR throughoutSAGWA DR TALAHI DR the Phase 3 work area SOUTHGATE RD for the duration of work KENESAW AVE TemporaryBLUFF VIEW RD lane closures as needed KEOWEE AVE TUGALOO DR W E S Map LegendAGAWELA AVE TALILUNA AVE Current Work Zones Sequoyah Greenway CHEROKEE BLVD. -

The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1923 The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763 David P. Buchanan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, David P., "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1923. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by David P. Buchanan entitled "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in . , Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: ARRAY(0x7f7024cfef58) Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) THE RELATIONS OF THE CHEROKEE Il.J'DIAUS WITH THE ENGLISH IN AMERICA PRIOR TO 1763.