(ERB) and Ethics: Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steiner Waldorf Education and the Irish Primary Curriculum: a Time of Opportunity

Steiner Waldorf Education and the Irish Primary Curriculum: A Time of Opportunity By Jonathan Angus At The Institute of Technology Sligo Supervised by Doireann O’Connor A Thesis Submitted to the Higher Education and Training Awards Council for the Award of Masters of Arts July 2011 1 Abstract The object of this research was to study the implications of Steiner Waldorf pedagogy delivered in National Schools, and to consider both its viability and usefulness. This research used both qualitative and quantitative methods of primary and secondary research. A review was carried out of the literature of the Waldorf movement internationally and specific to Ireland. A history of the Waldorf movement in Ireland, as well as a brief overview of the history of Irish publicly funded education, were both created from published literature, schools' records, and websites. Interviews were conducted with all of the full time teachers at both of the temporarily recognised Steiner National Schools, Mol an Oige and Raheen Wood. Data was compiled that showed a significant drop in the Steiner Waldorf-specific background and training of newly hired teachers at the two schools over the three years since recognition, resulting today in the majority of teachers lacking any previous Steiner Waldorf training. In fulfilling this objective, it was found that the value system of Steiner schools can be a useful addition to the options created for the families of Ireland. The general aims of the Primary School Curriculum were found to be in complete accord with those of the Steiner Waldorf approach, and multiple aspects of Waldorf pedagogy were identified which can be employed to deliver the curriculum in a vibrant and creative way. -

Programma Scolastico in Irlanda

PROGRAMMA SCOLASTICO IN IRLANDA PROGRAMMA SCUOLE PUBBLICHE La quota INCLUDE -Sistemazione in famiglia ospitante in camera singola o doppia con trattamento di pensione completa (packed lunch nei giorni di scuola) - Guardianship /tutore dedicato per tutta la durata del soggiorno - Lezioni presso la High School statale irlandese- Convalida della frequentazione scolastica - 6 TrasferimentI andata/ritorno dall’aeroporto alla famiglia ospitante, se nella zona di Dublino. Per studenti fuori dal centro di Dublino verrà organizzato transfer pubblico fino a Dublino centro e transfer privato con assistenza in aeroporto. Trasferimento incluso anche per il rientro vacanze pasquali. - Meeting pre-partenza in Italia - Settimana di orientamento all’inizio del soggiorno 23- 27 Agosto. - Assistenza del coordinatore locale per tutta la durata del soggiorno, numero per emergenze 24/7 - Assistenza in loco per l’acquisto di libri e divisa - Materiale informativo pre-partenza La quota NON INCLUDE -Viaggio andata/ritorno -Non è incluso il soggiorno per le vacanze di Natale -Spese per la divisa e materiale didattico circa 400 , corsi extra di inglese, etc. € - Eventuali spese di trasporto locale - Attività extra proposte dalla scuola (gite, equitazione, etc.) - Spese personali - Assicurazione COSTI SCUOLA STATALE Costi a partire da: ANNO SCOLASTISCO : 12.900 € TERM 1 :Dal 23 agosto al 22 Dicembre 2021- 17 settimane 8.250 € TERM 2 : Dal 6 gennaio all ‘8 Aprile -13 settimane 7.330 € TERM 1 & 2: Dal 23 Agosto 2021 all’8 Aprile 2022 -30 settimane 12.225 € TERM 2 & 3: Dal 6 Gennaio al 3 Giugno (non incluse vacanze Pasquali) -19 settimane 8.470 -21 settimane (incluse le vacanze pasquali ) 9.070. -

Schedule 2015

Schedule 2015 0 Adjudicators Choral – Comps 1-3 David Leigh Comps 4-8 Michael McGlynn Recorders Hilda Milner Piano Catherina Lemoni Lorna Horan Orchestra Philip Thomas Vocal Áine Mulvey Edith Forrest Emmanuel Lawler Mary Pembrey Toni Walsh Irish Vocal Deirdre Moynihan Chamber Music Philip Thomas Strings William Butt Woodwind & Brass Rebecca Halliday Percussion Eddie McGinn Classical Guitar Michael O’Toole Rock Guitar Shane Keogh Rock Bands Ollie Cole Traditional groups Oisín Morrison Own Performed Song Ollie Cole 1 Competitions-Where are they? Friday Choirs Page Unison or 2-part Primary 1. Taney School Cup 2.00 p.m. 5 Choirs Myles Hall 2-part Choirs 1st - 3rd Year 2. Epworth Cup 3.50 p.m. 5 only Myles Hall 3. 3-part Choirs SSA Myles Hall Rathdown Cup 5.15 p.m. 5 4. 3-part Choirs SAB Myles Hall David Wilson Cup 6.20 p.m. 6 5. 3 or 4-part Boys’ Choirs Myles Hall Frank Hughes Cup 7.00 p.m. 6 6. 4-part Girls’ Choirs Myles Hall William G. Kirkpatrick Cup 7.45 p.m. 6 Unaccompanied Vocal 7. Marathon Cup 8.15 p.m. 6 Ensemble Myles Hall 8. 4-part Choirs SATB Myles Hall William J. Watson Cup 9.25 p.m. 6 Recorders 9. Recorder Solo Primary Room T3 Primary Recorder Cup 2.00 p.m. 10 13. Recorder Ensemble Primary Room T3 3.20 p.m. 10 Solo Singing Solo Singing Classical MA1 Notre Dame Cup 1st 28A 2.00 p.m. 7 U16A Auditorium Round Solo Singing Classical Room Notre Dame Cup 1st 28B 2.00 p.m. -

LHA 2020 Player Development Programme V4.1 for Circulation

LHA Academy Player & Coach Development Programme Version 4.1 Ann Ronan, 08 July 2020 Player Development Programme Objectives • Identify and develop junior players across the province – Existing skills and potential are important; focus is on • Skills and Technical development • Performance Panels - Tactical and games development • Performance Panels – Physical strength and conditioning (Injury prevention) development • Identify and select regional and provincial representative teams • Talent Identification : Skilful players with athletic ability / Athletic players with potential to develop required skills • Participate in Inter-Regional competitions and National U15 Festival • Inter-Provincial matches and final tournament • International Tournaments • Ensure that there is a clear development pathway for players all the way through to national squads • Increased participation of Leinster players on national panels • Ensure there is a clear development pathway for coaches – leading to national panel coaching roles • Roles for Head Coach at District / Region / Inter-Provincials (ideally have HI Level 2 or are working towards Level 2) • Assistant coach roles at every level (must have HI Level 1) • Shadow/Development coaches from clubs/schools to support the district centres (Voluntary… ideally have HI level 1) Key Success Factors / Key Measures • To be successful the programme requires • A full time development programme manager with administrative support • A high level of support for player development from within the clubs, schools and -

Napd Meets the Minister

NAPDPRINCIPALS AND DEPUTY PRINCIPALS Leader NAPDNAPD MEETSMEETS THETHE MINISTERMINISTER September A Publication of the National Association of 2014 Principals & Deputy Principals NAPDPRINCIPALS AND DEPUTY PRINCIPALS NAPDPRINCIPALS AND DEPUTY PRINCIPALS CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTSESHA TAKES TO CROATIALeader FOR THE BURNING ISSUES BIG CONFERENCE Page 15Page 22 Page 27 Page 29 Tom Collins Lucy McCullen Dubrovnik Mary & David FEATURES 34 43 The Solas Strategy The Very Useful Guide 7 A critical look at how the Solas strategic plan will impact on Further Education Jan O’Sullivan 48 Pat Maunsell Meeting the newly-appointed Minister Comment for Education and Skills 45 Derek West The New School Leaders ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Listings of recently-made appointments of 12 principals and deputy principals in all nine 6 Droichead Student Voice regions 10 Autumn in-service A challenge for school leadership Domnall Fleming REGULARS 11 Cornmarket Advice 14 Conference 15 NEW!! 4 The Burning Issues Presidential Musings 19 Respecting our Flag Tom Collins shares his insights into the 20 Child Protection Law most pressing concerns issues for Irish 5 education The National Executive 21 Latest ESRI Research Barry O’Callaghan 26 Iguana 22 NEW!! 29 The Leader Reader 27 ESHA Conference The Deputy Principal First in a series considering the special 24 28 Spirit of Community role of the DP Phoenix 36 The Arts Supplement Derek West 42 Regional speakers 32 NAPDPRINCIPALS AND DEPUTY PRINCIPALS 47 Bulletin Board Young Social Innovators Leader Looking for support for a dynamic schools This month’s cover: project Our thanks to Charlie McManus, for taking the portraits of Jan O’Sullivan, paving the way to the interview on Page 7 Bronagh O’Hagan and promising wondrous landscapes in the NAPD Calendar for 2015. -

Kosten Irland

Kosten Irland Die Gesamtkosten setzen sich aus mehreren Einzelpreisen zusammen. Zu den einzelnen Schulpreisen addieren sich unsere Servicegebühr, Flugkosten, Schuluniformkosten, spezielle Fächer. Zusätzlich können freiwillige Versicherungen, Taschengeld, zusätzliche Reisen oder Ausflüge hinzu kommen. Die Schulkosten in Irland variieren von Schule zu Schule. Die angegebenen Preise beinhalten Schul- und Gastfamilien-/ Internatsgebühr, Anmeldegebühren. eventuelle Kosten für spezielle Fächer und Uniform sind nicht enthalten Preise in Euro und vorbehaltlich eventueller Preisänderungen fehlende Angaben auf Nachfrage Boarding School / Internat 1 term 2 terms 1 Schuljahr September - Dezember Januar - Juni Jan. – Jul. Alexandra College (Privatschule) 27.850 € Blackrock College (Privatschule) 26.055 € (29.820 €) Dundalk Grammar School (Privatschule) 16.585 € Glenstal Abbey (Privatschule) 26.955 € (30.670 €) St. Columba´s College Junior (Privatschule) 27.830 € (32.085 €) St. Columba´s College Senior (Privatschule) 31.985 € (36.965 €) The King´s Hospital (Privatschule) 26.165 € (27.090 €) Wesley College (Privatschule) 21.480 € (23.960 €) Rathdown School (Privatschule) 28.920 € Wilson´s Hospital School (Privatschule) 16.895 € Newtown School (Privatschule) 18.640 € Bandon Grammar School (Privatschule) 18.975 € Villiers School (Privatschule) 21.425 € (24.205 €) Villiers School IB (Privatschule) 25.135 € (28.585 €) Schule / Gastfamilie 1 term 2 terms 1 Schuljahr September - Dezember Januar - Juni Jan. – Jul. John Scottus School (Privatschule) 9.670 € 10.220 € 16.975 € St. Columba´s College (Privatschule) 21.950 € St. Killian´s German School (Privatschule) 16.975 € NAIS (Privatschule) 36.620 € St. Conleth´s College Junior (Privatschule) 18.040 € St. Conleth´s College Senior (Privatschule) 18.255 € Stratford College (Privatschule) 16.470 € Dublin Academy of Education (Privatschule) 19.100 € Sutton Park School (Privatschule) 11.230 € 12.330 € 19.425 € The High School (Privatschule) 17.545 € Institute of Education (Privatschule) 25.710 € (22.620 €) Marlan College 11.480 € St. -

Revised Criteria and Procedures for Establishment of New Primary Schools

Revised Criteria and Procedures for Establishment of New Primary Schools Report of the Commission on School Accommodation February 2011 FOREWORD..........................................................................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................5 SUMMARY OF PART ONE – CURRENT POSITION....................................................................................5 SUMMARY OF PART TWO – FUTURE SCHOOL PLANNING......................................................................6 SUMMARY OF PART THREE – PROPOSALS AND RECOMMENDATIONS....................................................7 PART ONE – CURRENT POSITION ...............................................................................................10 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................10 TERMS OF REFERENCE........................................................................................................................10 METHODOLOGY FOR THE REVIEW ......................................................................................................10 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ..................................................................................................................11 PROCEDURE FOR THE OPENING OF NEW SCHOOLS DURING NSAC’S TERM OF OFFICE .........................11 CHANGE IN DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS ....................................................................................................12 -

Substance Abuse NEW Jan 2011 Layout 1.Qxd

DUBLIN FRONT Covers2011:Layout 1 27/01/2011 09:26 Page 5 SHARING EXPERIENCES AND SUGGESTIONS AROUND ALCOHOL & SUBSTANCE ABUSE A COLLABORATIVE GUIDE FOR PARENTS Substance Abuse Cover Dec 2010:Layout 1 27/01/2011 09:34 Page 2 A School & Community Initiative Supported By NAPD PRINCIPALS AND DEPUTY PRINCIPALS National Association of Principals and Deputy Principals Cumann Náisiúnta Príomhoidí agus Príomhoidí Tánaisteacha Sharing Experiences And Suggestions Around Alcohol & Substance Abuse A Collaborative Guide For Parents, 2nd Edition, 2011. Copyright © Brian Wall, 2011. A not-for-profit initiative by the author and the schools listed on page 32 and endorsed by the above organisations. No part of this publication may be reproduced for financial gain. Permission to copy may be obtained provided it is for non-commercial use; the content is not modified, and is used in collaboration with other local schools. Individual parents/guardians are free to download copies for personal use from www.drugs.ie. Suggestions as to how this booklet may be improved should be sent by post to Brian Wall, St. Mary’s College, C.S.Sp., Rathmines, Dublin 6. Design, layout and print by CRM Design + Print Ltd., Dublin 12 • 01-4290007 Substance Abuse NEW Jan 2011:Layout 1 27/01/2011 09:38 Page 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 2 2. The Dangers ................................................................................................................... 2 -

2012 Admissions Cycle

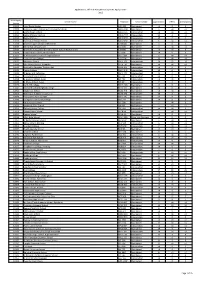

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2012 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <4 0 0 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent <4 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 15 4 4 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 6 <4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained 4 <4 <4 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 0 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <4 0 0 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 6 <4 <4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 15 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 26 13 10 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 <4 <4 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 0 0 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 18 6 5 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 4 <4 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <4 0 0 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 <4 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 7 4 4 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <4 0 0 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <4 0 0 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <4 <4 0 10045 Wellington College, -

Results Selection Test 2018

Results Selection Test 24 February 2018 Name Year of Study School Ahn, Ellie 4 Alexandra College, Dublin Akshay, Devon 5 Oatlands College Dublin Alkayed, Yusuf 5 Ballinteer Community School Bonar, Conal 5 St Eunan’s School Bond, Nicki 4 Wesley College Dublin Byrne, Jessica 6 Presentation Secondary School, Wexford Callegari, Rosa 5 John Scottus School Clement, Laurence 3 Lycée Francais D’Irlande dublin Coakley, Alana 3 Rathdown Senior School Costello, Emma 6 Wesley College Dublin Curry, Beinginn 4 St Joseph of Cluny, Killiney Fannin, Aine 4 Ardee Community School Finegan, Dexter 5 Oatlands College Dublin Halpenny, David 4 Blackrock College Dublin Hunag, Amanda 5 Alexandra College, Dublin Ingrosso, Gaia 5 St Tiernan’s Community School Jones, Alice 6 Skerries Community College Joyce, Daniel 4 Patrician Secondary School Newbridge Kasa, Adi 5 St Pauls CBS Dublin Kelly, Siofra 5 Manor House School Kim, Wansoo 5 CBS Monkstown Kisane, Hanna 4 St Joseph of Cluny, Killiney Long, Roisin 4 Sandford Park School Mbunga, John Bless 5 St Pauls CBS McKeever, Max 5 St Michael’s School Dublin Neamti, Peter 5 Colaiste Pobail Setanta Nowosad, Mateusz 5 Athlone Community College O’Connell, Michael 5 Catholic University School Dublin O’Neill, Niamh 5 East Glendalough School Pochinkov, Nicholas 6 St Gerard’s School Bray Ramesh, Krishna 4 Loreto School, Wexford Seredych, Lubomir 5 Ballinteer Community School Shkarin, Alexander 4 Methodist School Belfast Siriphak, Thanadorn 5 St Tiernan’s Community School Smith, Jessica 5 Alexandra College, Dublin Szmagara, Martyna 6 Rockford Manor Temple, Julia 4 Loreto Bray Secondary School !1 Name Year of Study School Wu, Yuan 5 Holy Faith Secondary School Xie, Tianyiwa 4 Alexandra College, Dublin Xiong, Yuelin (Mandy) 5 Alexandra College, Dublin Yu, Ming 5 Institute of Education, Dublin Zubascu, Maria 4 St Mary’s Glasnevin Bermingham, Andrew 5 Belvedere College Dublin Tiarnan, Ryan 5 Belvedere College Dublin Sagaseta Paga, Carlos 5 St Tiernan’s Community School Casper, Wang 4 St Columba’s College !2. -

ANNUAL REPORT for the Year Ending 16 March 1998 INTRODUCTION

ANNUAL REPORT for the year ending 16 March 1998 INTRODUCTION On the occasion of the 1,400th anniversary of the death of Colum Cille, 9 June 1997, the Academy visited Derry. The Cathach manuscript, traditionally said to have been written by Colum Cille, was placed on display in the Guildhall, together with its eleventh-century metal shrine, and attracted large numbers of visitors. A discourse, “Colum Cille: the Continental evidence”, was given in the morning at Magee College by Dr J.-M. Picard of the National University of Ireland, Dublin. In the evening, after a short presentation by Mr Risteard MacGabhann, Department of Irish, University of Ulster at Coleraine, and Professor Próinséas Ní Chatháin of the National University of Ireland, Dublin, on Amra Choluimb Chille (“Elegy of Colum Cille”), attributed to Dallán Forgaill, three Members, Dr S. Heaney, Professor R.M. Flannery and Dr B.M.S. Campbell, signed the roll, Dr Heaney and Professor Flannery signing in the city where they went to school. Dr Heaney presented the Academy with a signed manuscript poem, Colmcille the scribe, translated from the old Irish “Sgíth mo chrob ón scríbinn”. Professor Flannery, who was admitted to Honorary Membership, was awarded the 1998 Will Allis Prize for advancing the understanding of recombination processes. Ms Siobhán O’Rafferty was appointed Librarian of the Academy on 20 June 1997. The manu- script and rare book collections of the Academy continue to draw large numbers of scholars from Ireland and abroad. The medical manuscript 23.P.10, the fifteenth-century Book of the O’Lees and MS.24.P.26, a medical treatise of the same century compiled by the O’Hickeys, were conserved and repaired with funds provided by the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, Stuttgart, to whom we are grateful for enabling this and earlier conservation work. -

Chief Executive's Report Pre -Draft CDP 2022-2028

Dn Review of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Development Plan 2016-2022 & Preparation of a New County Development Plan 2022-2028 Chief Executive’s Report on Pre – Draft Consultation Process Report to Council Under Section 11 (4) Of the Planning and Development Act 2000, (as amended). April 2020 Part 1: Introduction to Chief Executive’s Report 1 Part 1: Introduction to Chief Executive’s Report Contents Table of Contents Page No. Part 1 Introduction to the Chief Executive’s Report Table of Contents 2 Acronyms 6 1 Introduction 8 1.1 Format of Report 9 1.2 Legislative Background for the Chief Executive’s Report 10 1.3 Pre-Draft Consultation Process 11 1.4 Challenges 12 1.5 Overview of nature of submissions received and recommendations made 13 2 Draft Core Strategy 18 2.1 Directions and the Draft Core Strategy 18 2.2 Strategic Overview 18 2.3 Population Targets and Land Availability 20 2.4 Draft Core Strategy 21 Part 2 Summary of Submissions by The Eastern Midlands Regional Authority, The National Transport Authority and the Office of the Planning Regulator and the Executive’s Opinion & Recommendations 2.1 Eastern and Midland Regional Authority 23 2.2 National Transport Authority (NTA) 29 2.3 Office of the Planning Regulator (OPR) 32 Part 3 Summary of Submissions & the Executive’s Opinion & Recommendations Section 1 Strategic Overview 39 1.1 Strategic Vision 40 1.2 Core Strategy 41 1.3 Settlement Strategy 44 2 Part 1: Introduction to Chief Executive’s Report Contents Page No. 1.4 Enabling Infrastructure 49 1.5 Local Area Plans 49 Section 2 Climate