This Dissertation, Titled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

COMING MARCH 30! WOMEN's HISTORY TRIP to Cambridge

COMING MARCH 30! WOMEN’S HISTORY TRIP to Cambridge, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, to see the Harriet Tubman Museum and the Annie Oakley House. Call 301-779-2161 by Tuesday, March 12 to reserve a seat. CALL EARLY! Limited number of seats on bus - first ones to call will get available seats. * * * * * * * MARCH IS WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH – AND HERE ARE SOME WOMEN FROM MARYLAND’s AND COTTAGE CITY’s PAST! By Commissioner Ann Marshall Young There are many amazing women in Maryland and Cottage City’s history. These are just a few, to give you an idea of some of the “greats” we can claim: Jazz singer Billie Holiday (1915 – 1959) was born Eleanora Fagan, but took her father’s surname, Holiday, and “Billie” from a silent film star. As a child she lived in poverty in East Baltimore, and later gave her first performance at Fell’s Point. In 1933 she was “discovered” in a Harlem nightclub, and soon became wildly popular, with a beautiful voice and her own, truly unique style. Her well-known song, “Strange Fruit,” described the horrors of lynchings in Jim Crow America. Through her singing, she raised consciousness about racism as well as about the beauties of African-American culture. Marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson (1907-1964) wrote the book Silent Spring, which, with her other writings, is credited with advancing the global environmental movement. Although opposed by chemical companies, her work led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides, and inspired a grassroots environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. -

Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation

09-Mollin 12/2/03 3:26 PM Page 113 The Limits of Egalitarianism: Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation Marian Mollin In April 1947, a group of young men posed for a photograph outside of civil rights attorney Spottswood Robinson’s office in Richmond, Virginia. Dressed in suits and ties, their arms held overcoats and overnight bags while their faces carried an air of eager anticipation. They seemed, from the camera’s perspective, ready to embark on an exciting adventure. Certainly, in a nation still divided by race, this visibly interracial group of black and white men would have caused people to stop and take notice. But it was the less visible motivations behind this trip that most notably set these men apart. All of the group’s key organizers and most of its members came from the emerging radical pacifist movement. Opposed to violence in all forms, many had spent much of World War II behind prison walls as conscientious objectors and resisters to war. Committed to social justice, they saw the struggle for peace and the fight for racial equality as inextricably linked. Ardent egalitarians, they tried to live according to what they called the brotherhood principle of equality and mutual respect. As pacifists and as militant activists, they believed that nonviolent action offered the best hope for achieving fundamental social change. Now, in the wake of the Second World War, these men were prepared to embark on a new political jour- ney and to become, as they inscribed in the scrapbook that chronicled their traveling adventures, “courageous” makers of history.1 Radical History Review Issue 88 (winter 2004): 113–38 Copyright 2004 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

20Th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program Women's and Gender Studies Program 2005 20th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators Safoura Boukari Western Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wgsprogram Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Boukari, Safoura, "20th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators" (2005). Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wgsprogram/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Women's and Gender Studies Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Manuscript; copyright 2005(?), S. Boukari. Used by permission. 20TH CENTURY BLACK WOMEN'S STRUGGLE FOR EMPOWERMENT IN A WHITE SUPREMACIST EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM: TRIBUTE TO EARLY WOMEN EDUCATORS by Safoura Boukari INTRODUCTION The goal in this work is to provide a brief overview of the development of Black women‟s education throughout American history and based on some pertinent literatures that highlight not only the tradition of struggle pervasive in people of African Descent lives. In the framework of the historical background, three examples will be used to illustrate women's creative enterprise and contributions to the education of African American children, and overall racial uplift. -

Senate the Senate Met at 10:31 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MARCH 22, 2018 No. 50 Senate The Senate met at 10:31 a.m. and was from the State of Missouri, to perform the It will confront the scourge of addic- called to order by the Honorable ROY duties of the Chair. tion head-on and help save lives. For BLUNT, a Senator from the State of ORRIN G. HATCH, rural communities, like many in my Missouri. President pro tempore. home State of Kentucky, this is a big Mr. BLUNT thereupon assumed the deal. f Chair as Acting President pro tempore. The measure is also a victory for PRAYER f safe, reliable, 21st century infrastruc- The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY ture. It will fund long overdue improve- fered the following prayer: LEADER ments to roads, rails, airports, and in- Let us pray. land waterways to ensure that our O God, our Father, may life’s seasons The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- pore. The majority leader is recog- growing economy has the support sys- teach us that You stand within the tem that it needs. shadows keeping watch above Your nized. own. We praise You that You are our f Importantly, the bill will also con- tain a number of provisions to provide refuge and strength, a very present OMNIBUS APPROPRIATIONS BILL help in turbulent times. more safety for American families. It Lord, cultivate within our lawmakers Mr. -

![INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2462/institution-pennsylvania-state-dept-of-education-harrisburg-pub-date-84-note-104p-892462.webp)

INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 253 618 UD 024 065 AUTHOR Waters, Bertha S., Comp. TITLE Women's History Week in Pennsylvania. March 3-9, 1985. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use, (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; tt dV Activities; Disabilities; Elementary Sec adary Education; *Females; *Government (Administrative body); *Leaders; Learning Activities; *Politics; Resour,e Materials; Sex Discrimination; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *National Womens History Week Project; *Pennsylvania ABSTRACT The materials in this resource handbook are for the use of Pennsylvania teachers in developing classroom activities during National Women's History Week. The focus is on womenWho, were notably active in government and politics (primarily, but not necessarily in Pennsylvania). The following women are profiled: Hallie Quinn Brown; Mary Ann Shadd Cary; Minerva Font De Deane; Katharine Drexel (Mother Mary Katharine); Jessie Redmon Fauset; Mary Harris "Mother" Jones; Mary Elizabeth Clyens Lease; Mary Edmonia Lewis; Frieda Segelke Miller; Madame Montour; Gertrude Bustill Mossell; V nnah Callowhill Penn; Frances Perkins; Mary Roberts Rinehart; i_hel Watersr Eleanor Roosevelt (whose profile is accompanied by special activity suggestions and learning materials); Ana Roque De Duprey; Fannie Lou Hamer; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper; Pauli Murray; Alice Paul; Jeanette Rankin; Mary Church Terrell; Henrietta Vinton Davis; Angelina Weld Grimke; Helene Keller; Emma Lazarus; and Anna May Wong. Also provided are a general discussion of important Pennsylvania women in politics and government, brief profiles of Pennsylvania women currently holding Statewide office, supplementary information on women in Federal politics, chronological tables, and an outline of major changes in the lives of women during this century. -

The Spiritof Howard

WINTER 11 magazine SpiritThe f o Howard 001 C1 Cover.indd 1 2/15/11 2:34 PM Editor’s Letter Volume 19, Number 2 PRESIDENT Sidney A. Ribeau, Ph.D. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING Thef Spirit o Howard Judi Moore Latta, Ph.D. EDITOR Raven Padgett Founders Library, named to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001, is such PUBLICATIONS SPECIALIST an iconic structure. While the clock tower that sits atop the library is one of the most LaShandra N. Gary recognizable physical symbols of Howard, the collection of history housed within CONTRIBUTING WRITERS the building may best represent the spirit of the University. Erin Evans, Sholnn Freeman, Damien T. The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center preserves centuries of African and Frierson, M.S.W., Fern Gillespie, African-American history. Snapshots of history archived in the center include docu- Kerry-Ann Hamilton, Ph.D., Ron Harris, ments, photographs and objects that help piece together an often fragmented story. Shayla Hart, Melanie Holmes, Otesa Middleton Miles, Andre Nicholson, Ashley FImagine reading firsthand the words of Olaudah Equiano, a former slave whose 1789 Travers, Grace I. Virtue, Ph.D. narrative is one of the earliest known examples of published writings by an African writer. Moorland-Spingarn holds at least one copy of the eight editions, including CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS a signed version. Other relics include 17th-century maps, 18th- and 19th-century Ceasar, Kerry-Ann Hamilton, Ph.D., masks, hundreds of periodicals and 30,000 bound volumes on the African Diaspora. Marvin T. Jones, Justin D. Knight This jewel on the yard is a unique structure that attracts scholars from all over the world, providing access to treasures that educate and enlighten. -

Finding Pauli Murray: the Black Queer Feminist Civil Rights Lawyer Priest Who Co-Founded NOW, but That History Nearly Forgot October 24, 2016

Finding Pauli Murray: The Black Queer Feminist Civil Rights Lawyer Priest who co-founded NOW, but that History Nearly Forgot October 24, 2016 Photo courtesy Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University “If one could characterize in a single phrase the contribution of Black women to America, I think it would be ‘survival with dignity against incredible odds’…” - Pauli Murray, “Black Women-A Heroic Tradition and a Challenge” (1977) She was an African-American civil rights activist, who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Petersburg, Va. 15 years before Rosa Parks; and she organized restaurant sit-ins in Washington, D.C. 20 years before the Greensboro sit- ins. She was one of the most important thinkers and legal scholars of the 20th century, serving as a bridge between the civil rights and women’s rights movements. Co-founder of NOW - She was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women, a feminist icon ahead of her time who challenged race and gender discrimination in legal, societal, academic and religious circles. And yet today, not many would recognize the name of the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray – let alone her indelible impact on American law, civil rights and women’s rights. As a black, queer, feminist woman, Pauli Murray has been almost completely erased from the narrative. It is time she was recognized. A Remarkable Life - Murray’s life and her remarkable accomplishments are coming back into focus as the National Trust for Historic Preservation considers designating the Pauli Murray childhood home at 906 Carroll Street in Durham, N.C. -

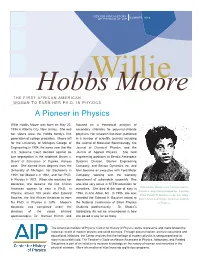

Hobbs Moore Was Born on May 23, Focused on a Theoretical Analysis of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS AT AIP SUMMER 2014 Willie Hobbs Moore THE FIRST AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMAN TO EARN HER PH.D. IN PHYSICS A Pioneer in Physics Willie Hobbs Moore was born on May 23, focused on a theoretical analysis of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. She and secondary chlorides for polyvinyl-chloride her sisters were the Hobbs family’s first polymers. Her research has been published generation of college graduates. Moore left in a number of scientific journals including for the University of Michigan College of the Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy, the Engineering in 1954, the same year that the Journal of Chemical Physics, and the U.S. Supreme Court decided against de Journal of Applied Physics. She held jure segregation in the landmark Brown v. engineering positions at Bendix Aerospace Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Systems Division, Barnes Engineering case. She earned three degrees from the Company, and Sensor Dynamics Inc. and University of Michigan: her Bachelor’s in later became an executive with Ford Motor 1958, her Master’s in 1961, and her Ph.D. Company, working with the warranty in Physics in 1972. When she received her department of automobile assembly. She doctorate, she became the first African was also very active in STEM education for American woman to earn a Ph.D. in minorities. She died at the age of sixty in Willie Hobbs Moore circa 1958 pictured in Women in Engineering Magazine. Courtesy Physics, almost 100 years after Edward 1994, in Ann Arbor, MI. In 1995, she was of the Ronald E. -

A History of the Conferences of Deans of Women, 1903-1922

A HISTORY OF THE CONFERENCES OF DEANS OF WOMEN, 1903-1922 Janice Joyce Gerda A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2004 Committee: Michael D. Coomes, Advisor Jack Santino Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen M. Broido Michael Dannells C. Carney Strange ii „ 2004 Janice Joyce Gerda All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael D. Coomes, Advisor As women entered higher education, positions were created to address their specific needs. In the 1890s, the position of dean of women proliferated, and in 1903 groups began to meet regularly in professional associations they called conferences of deans of women. This study examines how and why early deans of women formed these professional groups, how those groups can be characterized, and who comprised the conferences. It also explores the degree of continuity between the conferences and a later organization, the National Association of Deans of Women (NADW). Using evidence from archival sources, the known meetings are listed and described chronologically. Seven different conferences are identified: those intended for deans of women (a) Of the Middle West, (b) In State Universities, (c) With the Religious Education Association, (d) In Private Institutions, (e) With the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, (f) With the Southern Association of College Women, and (g) With the National Education Association (also known as the NADW). Each of the conferences is analyzed using seven organizational variables: membership, organizational structure, public relations, fiscal policies, services and publications, ethical standards, and affiliations. Individual profiles of each of 130 attendees are provided, and as a group they can be described as professional women who were both administrators and scholars, highly-educated in a variety of disciplines, predominantly unmarried, and active in social and political causes of the era. -

JASMINE JONES, Phd Email: [email protected] | Web

JASMINE JONES, PhD Email: [email protected] | Web: http://seejazzwork.com SUMMARY My research addresses the sociotechnical challenges of making embedded computing socially acceptable in everyday life. My methodology includes ethnographic methods, development of novel IoT technologies, field studies, and artistic explorations. Domains: collective memory, health and wellness, assistive devices EDUCATION PhD in Information Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor § Advisor: Dr. Mark S. Ackerman § Thesis: “Crafting a Narrative Inheritance: A Design Framework for Intergenerational Family Memory” B.S. Computer Science, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) B.A. Interdisciplinary Studies: “Human-Computer Interaction in an International Cultural Context”, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) § Magna cum laude Visiting Scholar, Creative Interaction Design Lab, KAIST, South Korea Visiting Student, Human-Computer Interaction, University of Melbourne, Australia HONORS, FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Academic Fellowships 2019-20 BlackComputeHer Leadership Fellow 2018 Postdoctoral Fellow, Big10 Academic Alliance Professorial Advancement Initiative (PAI) 2016 NSF/Korea National Research Foundation GROW International Research Fellow 2016 Engaged Pedagogy Fellow, Center for Community-Engaged Academic Learning (Michigan) 2013-16 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship 2012-17 GEM Fellowship 2012-17 University of Michigan Rackham Merit Fellow 2012 Google Anita Borg Scholar - Finalist 2007-12 Meyerhoff Scholar (UMBC) 2007-12 CWIT Scholar (UMBC Center