Mood Disorders H • Mood Disorders - Psychological Disorders a Characterized by Disturbances of Mood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 3 Emotional Regulation

WEEK 3 EMOTIONAL REGULATION GOALS/OBJECTIVES: This optional treatment module contains information to allow the participants to better understand how their TBI is related to their emotional dysregulation. This module should be utilized if several participants have expressed issues with mood swings, or if collateral information suggests client issues with emotional dysregulation. Emotional dysregulation refers to the inability of a person to control or regulate their emotional responses to provocative stimuli. The primary goals of this week will be for participants to: ❑ Identify what occurs during their mood swings ❑ Better understand their emotional responses to various situations ❑ Allow participants to practice coping skills to reduce or navigate emotional outbursts ❑ Provide psycho-education on how emotional dysregulation is related to TBI, and facilitate discussion during group about coping with emotional dysregulation. T I M E : Allow 1.5 hours for the session. NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS: A minimum of four participants is recommended. © MINDSOURCE – Brain Injury Network 2018 WEEK 3 44 WEEK 3 PREPARATION VIDEO Watch the following video: https://youtu.be/Y02clqBzrbs For trainer info on emotional dysregulation and TBI, see: https://tinyurl.com/ahead-trainerinfo PRINT HANDOUTS ❑ Brain Injury and Emotion Regulation ❑ Mood Log ❑ Take Home Impressions These handouts can be found in the handout section for this week, the facilitator’s guide will indicate when these should be referenced. WRITE Write the following group rules on the white board for reference for participants throughout the treatment group: • Confidentiality: The information we discuss in this group is private, and members are expected to keep it that way. • Respect: Give your attention and consideration to participants, and they will do the same for you. -

Intervention a Process – Not an Event

Intervention A Process – Not an Event ® La Hacienda PO Box 1, 145 La Hacienda Way Hunt, Texas 78024 (800) 749-6160 www.lahacienda.com Table of Contents (Please Note: Throughout this guide, items in bold italics are not printed in the Participant’s Guide.) What, Why and How of Intervention 1 Intervention Program Description 2 Rights of Intervention Program Participants 3 Responsibilities of Intervention Program Participants 3 Outline of the Intervention Process 4 The Disease 5 Nature of the Disease 6 Progression of the Disease 7 Delusional Memory 8 The Intervention Concept and Goal 9 Intervention Presentation Guidelines 10 Documentation Preparation 12 Suggested Feelings Words 13 Documentation Sheet Example 14 Documentation Sheet 15 Substance Abuse: A Family Problem 16 Symptoms of Co-Dependency 17 Enabling 18 Enabling Worksheet 19 What Goes on in a Family? 20 Intervention Planning Worksheet 21 Practice of Presentations 22 Your Intervention Rules 23 Intervention Checklist and Last Minute Reminders 24 This page intentionally left blank. What, Why and How of Intervention What is Intervention? Why Intervene? In its simplest form, intervention on Alcoholism is a progressive, alcoholism or drug addiction happens each terminal disease characterized by time the dependent person is confronted delusion and denial. Left to his/her own with his/her use or related behavior. This devices, the addicted individual is doomed form of intervention is inadequate and to continue their downward spiral. They counterproductive. Following such an have a disease that makes them think they encounter the addiction worsens and the do not have a disease! We believe that the family and friends of the dependent become belief that an alcoholic/addict must “hit angry and frustrated and may avoid further bottom” and ask for help is a deadly myth. -

Life Mental Health

LIFE MENTAL HEALTH BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDERS TREATMENT & REFERRAL GUIDE MHealth–BR–005 Rev 2 January 2019 LIFE MENTAL HEALTH Bipolar Mood Disorders – Treatment Guide ■ How to recognise Bipolar Mood Disorder ■ Who to approach for treatment ■ Treatment options ■ Self help BIPOLAR MOOD DISORDER Bipolar mood disorder is more than just a simple mood swing. You may experience a sudden dramatic shift in the extremes of emotions. These shifts seem to have little to do with external situations. In the manic or high phase of the illness you are not just happy, but rather, ecstatic. A great burst of energy can be followed by severe depression, which is the low phase of the disease. Periods of fairly normal moods can be experienced between cycles. These cycles are different for different people. They can last for days, weeks, or even months. Although bipolar mood disorder can be disabling, it also responds well to treatment. Since many other diseases can masquerade as bipolar mood disorder, it is important that the person undergoes a complete medical evaluation as soon as possible after the first symptoms occur. What is bipolar mood disorder? Bipolar mood disorder is a physical illness marked by extreme changes in mood, energy and behaviour. That is why doctors classify it as a mood disorder. Bipolar mood disorder – which used to be known as manic depressive illness – is a mental illness involving episodes of serious mania and depression. The person’s mood usually swings from overly high and irritable to sad and hopeless, and then back again, with periods of normal mood in between. -

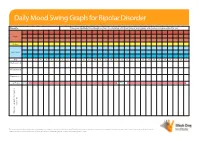

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder

Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Month: Please use this Daily Mood Graph to chart mood swings and the effects of any triggers and medications prescribed for you. Highs Normal Depressed Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Medication A Medication B Medication C e.g. Prozac 20mg 40mg events, etc. events, Notes on sleep patterns, triggers, triggers, on sleep patterns, Notes This document may be freely downloaded and distributed on condition no change is made to the content. The information in this document is not intended as asubstitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Not to be used for commercial purposes and not to be hosted electronically outside of the Black Dog Institute website. www.blackdoginstitute.org.au Daily Mood Swing Graph for Bipolar Disorder Instructions 1. Rate your mood at the end of each day by placing an ‘X’ in the appropriate box. If you have experienced both a ‘high’ and a ‘low’ mood on any given day, please rate both by putting an ‘X’ at each level 2. Write the name of the medications and doses you are taking 3. Next to each medication, please indicate the period of time you took the medication at the same dose by drawing an arrow through the relevant dates. If your dose changes during the course of the charting period, please write the new dose in the relevant box and continue the line. -

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms

Bipolar disorder symptoms What this fact sheet covers: • What is bipolar disorder • Sub-types of bipolar disorder • Symptoms of bipolar disorder • When to seek help for bipolar disorder • Key points to remember • Where to get more information What is bipolar disorder? Distinguishing between bipolar I Bipolar disorder is the name used to describe a and bipolar II set of ‘mood swing’ conditions, the most severe Bipolar I disorder is the more severe disorder, form of which used to be called ‘manic depression’. in the sense that individuals are more likely to The term describes the exaggerated swings of experience ‘mania’, have longer ‘highs’ and to mood, cognition and energy from one extreme to have psychotic episodes and be more likely to be the other that are characteristic of the illness. hospitalised. People with this illness suffer recurrent episodes Mania refers to a severely high mood where of high, or elevated moods (mania or hypomania) the individual often experiences delusions and/ and depression. Most experience both the highs or hallucinations. The severe highs which are and the lows. Occasionally people can experience referred to as ‘mania’ tend to last days or weeks. a mixture of both highs and lows at the same time, or switch during the day, giving a ‘mixed’ picture of symptoms. A very small percentage of sufferers Bipolar II disorder is defined as being less severe, of bipolar disorder only experience the ‘highs’. in that there are no psychotic features and People with bipolar disorder experience normal episodes tend to last only hours to a few days; a moods in between their mood swings. -

Mood Swings Background Information

Mood Swings Background Information: Everyone has “Ups” and “Downs” Just because someone may have occasional highs and lows with their moods, thankfully that does not automatically indicate a mood disorder. There is what is considered to be a “normal” range for our moods. Mood disorders (such as Bipolar Disorder) involve mood swings that go to higher and lower extremes than what would be considered to be “normal”. See below: The “Danger Zones” in the above diagram are characterized by problematic, potentially life-altering highs and lows that often coincide with intense emotions and at times regrettable behaviors. The Manic Danger Zone (Mania/Hypomania) – This characterized by an elevated mood state that is beyond just being excited or happy. The following is a list of some of the symptoms someone in this state may experience, however, the way individuals experience these mood swings can be different for each person. Therefore people often experience some of these symptoms but not others: Intense feelings of excitement and enthusiasm Increased energy Decreased need for sleep. (Staying up all night without getting tired) Increased confidence Which at times can progress toward: o Grandiosity – An unrealistic sense of superiority or an exaggerated sense of importance. Increase in pleasure-seeking activity – Someone in a manic state may find themselves engaging in increased sexual behavior, spending, drug/alcohol use Reckless decision making – For example, going into questionable business deals or taking other risks that you would not normally take because of being in an elevated mood state Agitation – Irritability and in some cases intense anger or even rage Psychosis – In more extreme cases, a prolonged manic state can result in losing touch with reality and for a limited number of people, hallucinations and delusional thinking The Depressive Danger Zone – Depressed mood in excess of “normal” sadness or dejection. -

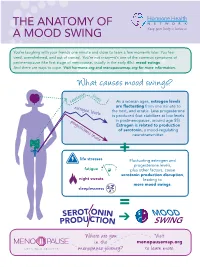

The Anatomy of a Mood Swing

THE ANatOMY OF A MOOD SWING You’re laughing with your friends one minute and close to tears a few moments later. You feel tired, overwhelmed, and out of control. You’re not crazy—it’s one of the common symptoms of perimenopause (the first stage of menopause, usually in the early 40s): mood swings. And there are ways to cope. Visit hormone.org and menopausemap.org for more information. What causes mood swings? levels serotonin As a woman ages, estrogen levels estrogen levels are fluctuating from one minute to the next, and erratic. Less progesterone is produced (but stabilizes at low levels progesterone levels in postmenopause, around age 55). Estrogen is related to production of serotonin, a mood-regulating neurotransmitter. + life stresses Fluctuating estrogen and progesterone levels, fatigue plus other factors, cause serotonin production disruption, night sweats leading to more mood swings. sleeplessness = MOOD ➔ SWING Where a re you Visit in the menopausemap.org menopause journey? to learn more. Dealing with symptoms of mood swings Avoid Talk to a therapist caffeine, or counselor alcohol, and spicy foods angry worried GLAD HAPPY Get enough sleep; appreciative BRA Eat a balanced, AFRAID hopeful VE being tired UNEAbadSY healthy diet silly STRONG affects your SAFE A with fruits, m JEALOUS FRUSTRA mood HELPLESS N amused vegetables, and cal X whole grains I TED Osad str essed defensive CONFIDENT optimistic U Y overwhelmed S elaxed r SORR GR bo A DEPRESSED r ed TEFUL judgmental Find healthy e l pleased ways to b a t i deal with Exercise r -

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of MINNESOTA Civil No. 12Cv538 (JNE/TNL) CYNTHIA BAKKE, Plaintiff, REPORT and RECOMMEND

CASE 0:12-cv-00538-JNE-TNL Document 27 Filed 07/01/13 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA Civil No. 12cv538 (JNE/TNL) CYNTHIA BAKKE, Plaintiff, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION v. CAROLYN W. COLVIN,1 ACTING COMMISSIONER OF SOCIAL SECURITY Defendant. Lionel H. Peabody, P.O. Box 10, Duluth, MN 55801, for Plaintiff. Ana H. Voss, Assistant United States Attorney, 300 South Fourth Street, Suite 600, Minneapolis, MN 55414, for Defendant. ____________________________________________________________________ TONY N. LEUNG, United States Magistrate Judge. Plaintiff Cynthia Bakke (“Bakke”) disputes the Commissioner’s denial of her application for disability insurance benefits (“DIB”). Judicial review in the United States District Court for the District of Minnesota is proper under 42 U.S.C. § 405. This matter is before the Court, United States Magistrate Judge Tony N. Leung, for a report and recommendation to the United States District Court on the parties’ cross motions for summary judgment. See 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1); D.Minn. LR 72.1-2. Based on the 1 Carolyn W. Colvin became Acting Commissioner of Social Security on February 14, 2013. She is substituted as the defendant pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 25(d). 1 CASE 0:12-cv-00538-JNE-TNL Document 27 Filed 07/01/13 Page 2 of 32 record and proceedings herein, IT IS HEREBY RECOMMENDED that Plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment be granted (Doc. No. 9); and Defendant’s motion for summary judgment be denied (Doc. No. 23). I. BACKGROUND A. Procedural History Bakke was 37-years old when she filed her application for DIB on August 17, 2010, and she alleges a disability onset date of July 25, 2010. -

Translational Research in Bipolar Disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2010) 15, 883–895 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/10 www.nature.com/mp FEATURE REVIEW Translational research in bipolar disorder: emerging insights from genetically based models G Chen1, ID Henter1 and HK Manji1,2 1Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA and 2Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Titusville, NJ, USA Bipolar disorder (BPD) is characterized by vulnerability to episodic depression and mania and spontaneous cycling. Because of marked advances in candidate-gene and genome-wide association studies, the list of risk genes for BPD is growing rapidly, creating an unprecedented opportunity to understand the pathophysiology of BPD and to develop novel therapeutics for its treatment. However, genetic findings are associated with major unresolved issues, including whether and how risk variance leads to behavioral abnormalities. Although animal studies are key to resolving these issues, consensus is needed regarding how to define and monitor phenotypes related to mania, depression and mood swing vulnerability in genetically manipulated rodents. In this study we discuss multiple facets of this challenging area, including theoretical considerations, available tests, limitations associated with rodent behavioral modeling and promising molecular–behavioral findings. These include CLOCK, glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK-3b), glutamate receptor 6 (GluR6), extracellular signal- regulated kinase-1 (ERK1), p11 (or S100A10), vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2 or SLC18A2), glucocorticoid receptors (GRs), Bcl-2-associated athanogene-1 (BAG1) and mitochondrial DNA polymerase-c (POLG). Some mutant rodent strains show behavioral clusters or activity patterns that cross-species phenocopy objective/observable facets of mood syndromes, and changes in these clustered behaviors can be used as outcome measures in genetic–behavioral research in BPD. -

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Behavioral and Emotional Aspects and Daily Routines of Arab Israeli Children

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Behavioral and Emotional Aspects and Daily Routines of Arab Israeli Children Rafat Ghanamah 1,2,*,† and Hazar Eghbaria-Ghanamah 2,† 1 Early Childhood Education Department, Oranim Academic College of Education, Kiryat Tevo’n 3600600, Israel 2 Edmond. J. Safra Brain Research Center for the Study of Learning Disabilities, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Negative psychological effects of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) have been identified in adults and children, such as anxiety and sleep disorders. However, research about the impact of this pandemic on children from ethnical minorities is scarce. We tested the effects of COVID-19 outbreak on psychological aspects and daily routines among Arab Israeli Children. An online cross- sectional survey was conducted among Arab Israeli parents, including behavioral and emotional aspects questionnaire and questions addressing using of screens, sleep, and physical activities. The results showed that, during the COVID-19 outbreak, 55.8% of the children asked to sleep in their parents’ bed and 45% expressed fears they did not have before. Most of the children showed increased irritability, constant mood swings and nervousness about limits and messages, and 41.4% showed sleep difficulties. Concerning adaptive behaviors, more than 50% of the parents reported that their Citation: Ghanamah, R.; Eghbaria-Ghanamah, H. Impact of child became wiser, lazier, and was able to adapt the limits and restriction of the COVID-19 outbreak. COVID-19 Pandemic on Behavioral Moreover, the children tended to increase their use of screens, used to sleep more time, and were and Emotional Aspects and Daily less active physically. -

BIPOLAR DISORDER: Identifying and Supporting Patients in Primary Care

BIPOLAR DISORDER: Identifying and supporting patients in primary care 6 Bipolar disorder can be challenging to diagnose and manage. It is often assumed to be recurrent major depression, until an episode of mania/hypomania occurs and the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is confirmed, usually by a Psychiatrist. Mood stabilising medicines, e.g. lithium and valproate, are the mainstay of pharmacological treatment. Monotherapy with antidepressants for a patient with bipolar disorder is associated with an increased risk of an episode of mania and should be avoided. A key role of general practice in the long-term management of patients with bipolar disorder is to educate the patient and their family about their condition, to encourage treatment adherence and a healthy lifestyle, to assess for treatment efficacy and monitor for adverse effects. The burden of bipolar disorder quarter of all completed suicides.6 Approximately 10 – 15% of people with untreated bipolar disorder can be expected to die Bipolar disorder first appeared in the medical literature in the due to suicide.2 1850s when alternating melancholia and mania were paired in a single condition.1 For a number of years the diagnosis was The severity of mania determines the type of bipolar termed “manic-depressive disorder”, but this was replaced by disorder bipolar disorder in 1980 when the Diagnostic and Statistical General Practitioners are often the first clinician to suspect a Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition (DSM-III) was patient has a mental illness. Although depression is the most released.1 Bipolar disorder is characterised by extreme mood common symptom of bipolar disorder, mania is the cardinal swings – from hopeless depression to euphoric or irritable feature and its severity is used by Psychiatrists to categorise mania – with each episode usually bookended by symptom- the patient’s disorder. -

Prevalence and Distribution Pattern of Mood Swings In

Angsukiattitavorn et al. BMC Psychiatry (2020) 20:191 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02605-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and distribution pattern of mood swings in Thai adolescents: a school- based survey in the central region of Thailand Suleemas Angsukiattitavorn1, Acharaporn Seeherunwong2*, Rungnapa Panitrat3 and Mathuros Tipayamongkholgul4 Abstract Background: Mood swings (MS) are a widely discussed psychiatric ailment of youthful patients. However, there is a lack of research about MS in this population. Methods: A school-based, cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the prevalence and distribution pattern of mood swings due to personal and contextual determinants in Thai adolescents in the central region of Thailand. Participants were 2598 students in high schools and vocational schools in Bangkok and three provinces in the central region of Thailand. Results: The prevalence of mood swings was 26.4%. It was highest among vocational students in Bangkok at 37.1%. MS were more common in adolescents who exhibited risk behaviors and who resided in hazardous situations. The probabilities of MS by characteristic in 15–24 years olds were: bullying involvement 36.9% (n = 1293), problematic social media use 55.9%(n = 127), high expressed emotion in family 36.6% (n = 1256), and studying in a vocational program 29.5% (n = 1216) and school located in Bangkok 32.4% (n = 561). Also, substance use was a risk for MS with cannabis use at 41.8%(n = 55) and heroin use at 48.0% (n = 25). Hierarchical logistic regression analysis showed that female gender, having a family history of mental problems, bullying involvement, problematic social media use, high expression of emotion in the family, and the interaction between vocational program enrollments and metropolitan/urban residence associated adolescent mood swings (p < .05).