Chapter 6 Chemical Reactivity and Mechanisms 6.1 Enthalpy (ΔH) - the Heat (Energy) Exchange Between the Reaction and Its Environment at Constant Pressure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Material 2.Pdf

Reactive Intermediates Source: https://www.askiitians.com/iit-jee-chemistry/organic-chemistry/iupac- and-goc/reaction-intermediates/ Table of Content • Carbocations • Carbanions • Free Radicals • Carbenes • Arenium Ions • Benzynes Synthetic intermediate are stable products which are prepared, isolated and purified and subsequently used as starting materials in a synthetic sequence. Reactive intermediate, on the other hand, are short lived and their importance lies in the assignment of reaction mechanisms on the pathway from the starting substrate to stable products. These reactive intermediates are not isolated, but are detected by spectroscopic methods, or trapped chemically or their presence is confirmed by indirect evidence. • Carbocations Carbocations are the key intermediates in several reactions and particularly in nucleophilic substitution reactions. Structure of Carbocations : Generally, in the carbocations the positively charged carbon atom is bonded to three other atoms and has no nonbonding electrons. It is sp 2 hybridized with a planar structure and bond angles of about 120°. There is a + vacant unhybridized p orbital which in the case of CH 3 lies perpendicular to the plane of C—H bonds. Stability of Carbocations: There is an increase in carbocation stability with additional alkyl substitution. Thus one finds that addition of HX to three typical olefins decreases in the order (CH 3)2C=CH 2>CH 3—CH = CH 2 > CH 2 = CH 2. This is due to the relative stabilities of the carbocations formed in the rate determining step which in turn follows from the fact that the stability is increased by the electron releasing methyl group (+I), three such groups being more effective than two, and two more effective than one. -

Reactions of Benzene & Its Derivatives

Organic Lecture Series ReactionsReactions ofof BenzeneBenzene && ItsIts DerivativesDerivatives Chapter 22 1 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene The most characteristic reaction of aromatic compounds is substitution at a ring carbon: Halogenation: FeCl3 H + Cl2 Cl + HCl Chlorobenzene Nitration: H2 SO4 HNO+ HNO3 2 + H2 O Nitrobenzene 2 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene Sulfonation: H 2 SO4 HSO+ SO3 3 H Benzenesulfonic acid Alkylation: AlX3 H + RX R + HX An alkylbenzene Acylation: O O AlX H + RCX 3 CR + HX An acylbenzene 3 Organic Lecture Series Carbon-Carbon Bond Formations: R RCl AlCl3 Arenes Alkylbenzenes 4 Organic Lecture Series Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution • Electrophilic aromatic substitution: a reaction in which a hydrogen atom of an aromatic ring is replaced by an electrophile H E + + + E + H • In this section: – several common types of electrophiles – how each is generated – the mechanism by which each replaces hydrogen 5 Organic Lecture Series EAS: General Mechanism • A general mechanism slow, rate + determining H Step 1: H + E+ E El e ctro - Resonance-stabilized phile cation intermediate + H fast Step 2: E + H+ E • Key question: What is the electrophile and how is it generated? 6 Organic Lecture Series + + 7 Organic Lecture Series Chlorination Step 1: formation of a chloronium ion Cl Cl + + - - Cl Cl+ Fe Cl Cl Cl Fe Cl Cl Fe Cl4 Cl Cl Chlorine Ferric chloride A molecular complex An ion pair (a Lewis (a Lewis with a positive charge containing a base) acid) on ch lorine ch loronium ion Step 2: attack of -

Lecture Outline a Closer Look at Carbocation Stabilities and SN1/E1 Reaction Rates We Learned That an Important Factor in the SN

Lecture outline A closer look at carbocation stabilities and SN1/E1 reaction rates We learned that an important factor in the SN1/E1 reaction pathway is the stability of the carbocation intermediate. The more stable the carbocation, the faster the reaction. But how do we know anything about the stabilities of carbocations? After all, they are very unstable, high-energy species that can't be observed directly under ordinary reaction conditions. In protic solvents, carbocations typically survive only for picoseconds (1 ps - 10–12s). Much of what we know (or assume we know) about carbocation stabilities comes from measurements of the rates of reactions that form them, like the ionization of an alkyl halide in a polar solvent. The key to connecting reaction rates (kinetics) with the stability of high-energy intermediates (thermodynamics) is the Hammond postulate. The Hammond postulate says that if two consecutive structures on a reaction coordinate are similar in energy, they are also similar in structure. For example, in the SN1/E1 reactions, we know that the carbocation intermediate is much higher in energy than the alkyl halide reactant, so the transition state for the ionization step must lie closer in energy to the carbocation than the alkyl halide. The Hammond postulate says that the transition state should therefore resemble the carbocation in structure. So factors that stabilize the carbocation also stabilize the transition state leading to it. Here are two examples of rxn coordinate diagrams for the ionization step that are reasonable and unreasonable according to the Hammond postulate. We use the Hammond postulate frequently in making assumptions about the nature of transition states and how reaction rates should be influenced by structural features in the reactants or products. -

Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties of the Trioxatriangulenium Carbocation and Its Interactions with Supramolecular Systems

View metadata,Downloaded citation and from similar orbit.dtu.dk papers on:at core.ac.uk May 03, 2019 brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research Database In Technology Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties of the Trioxatriangulenium Carbocation and its Interactions with Supramolecular Systems Reynisson, Johannes Publication date: 2000 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Reynisson, J. (2000). Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties of the Trioxatriangulenium Carbocation and its Interactions with Supramolecular Systems. Roskilde: Risø National Laboratory. Denmark. Forskningscenter Risoe. Risoe-R, No. 1191(EN) General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties of the Trioxatriangulenium Carbocation and its Interactions with Supramolecular Systems Jóhannes Reynisson OO O Risø National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark June 2000 1 Abstract Trioxatriangulenium (TOTA+, 4,8,12-trioxa-4,8,12,12c-tetrahydro- dibenzo[cd,mn]-pyrenylium) is a closed shell carbocation which is stable in its crystalline form and in polar solvents at ambient temperatures. -

Nonclassical Carbocations: from Controversy to Convention

Nonclassical Carbocations H H C From Controversy to Convention H H H A Stoltz Group Literature Meeting brought to you by Chris Gilmore June 26, 2006 8 PM 147 Noyes Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Nonclassical Carbocation Controversy - Winstein, Brown, and the Great Debate - George Olah and ending the discussion - Important nonclassical carbocations 3. The Nature of the Nonclassical Carbocation - The 3-center, 2-electron bond - Cleaving C-C and C-H σ−bonds - Intermediate or Transition state? Changing the way we think about carbocations 4. Carbocations, nonclassical intermediates, and synthetic chemistry - Biosynthetic Pathways - Steroids, by W.S. Johnson - Corey's foray into carbocationic cascades - Interesting rearrangements - Overman and the Prins-Pinacol Carbocations: An Introduction Traditional carbocation is a low-valent, trisubstituted electron-deficient carbon center: R superacid R R LG R R R R R R "carbenium LGH ion" - 6 valence e- - planar structure - empty p orbital Modes of stabilization: Heteroatomic Assistance π-bond Resonance σ-bond Participation R X H2C X Allylic Lone Pair Anchimeric Homoconjugation Hyperconjugation Non-Classical Resonance Assistance Stabilization Interaction Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Nonclassical Carbocation Controversy - Winstein, Brown, and the Great Debate - George Olah and ending the discussion - Important nonclassical carbocations 3. The Nature of the Nonclassical Carbocation - The 3-center, 2-electron bond - Cleaving C-C and C-H σ−bonds - Intermediate or Transition state? Changing the way we think about carbocations 4. Carbocations, nonclassical intermediates, and synthetic chemistry - Biosynthetic Pathways - Steroids, by W.S. Johnson - Corey's foray into carbocationic cascades - Interesting rearrangements - Overman and the Prins-Pinacol The Nonclassical Problem: Early Curiosities Wagner, 1899: 1,2 shift OH H - H+ Meerwein, 1922: 1,2 shift OH Meerwin, H. -

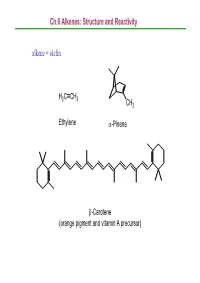

Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity Alkene = Olefin

Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity alkene = olefin H2CCH2 CH3 Ethylene α-Pinene β-Carotene (orange pigment and vitamin A precursor) Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity 6.1 Industrial Preparation and Use of Alkenes Compounds derived industrially from ethylene CH3CH2OH Ethanol CH3CHO Acetaldehyde CH3COOH Acetic acid HOCH2CH2OH Ethylene glycol ClCH2CH2Cl Ethylene dichloride H C=CHCl Vinyl chloride H2CCH2 2 O Ethylene oxide Ethylene (26 million tons / yr) O Vinyl acetate O Polyethylene Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity Compounds derived industrially from propylene OH Isopropyl alcohol H3CCH3 O Propylene oxide CH3 H3CCH CH2 Propylene Cumene (14 million tons / yr) CH3 CH3 Polypropylene Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity • Ethylene, propylene, and butene are synthesized industrially by thermal cracking of natural gas (C1-C4 alkanes) and straight-run gasoline (C4-C8 alkanes). 850-900oC CH (CH ) CH H + CH + H C=CH + CH CH=CH 3 2 n 3 steam 2 4 2 2 3 2 + CH3CH2CH=CH2 - the exact processes are complex; involve radical process H 900oC CH3CH2 CH2CH3 22H2CCH H2C=CH2 +H2 Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity • Thermal cracking is an example of a reaction whose energetics are dominated by entropy (∆So) rather than enthalpy (∆Ho) in the free-energy equation (∆Go = ∆Ho -T∆So) . ; C-C bond cleavage (positive ∆Ho) ; high T and increased number of molecules → larger T∆So Ch.6 Alkenes: Structure and Reactivity 6.2 Calculating Degree of Unsaturation unsaturated: formula of alkene CnH2n ; formula of alkane CnH2n+2 in general, each ring or double -

George A. Olah 151

MY SEARCH FOR CARBOCATIONS AND THEIR ROLE IN CHEMISTRY Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1994 by G EORGE A. O L A H Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute and Department of Chemistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1661, USA “Every generation of scientific men (i.e. scientists) starts where the previous generation left off; and the most advanced discov- eries of one age constitute elementary axioms of the next. - - - Aldous Huxley INTRODUCTION Hydrocarbons are compounds of the elements carbon and hydrogen. They make up natural gas and oil and thus are essential for our modern life. Burning of hydrocarbons is used to generate energy in our power plants and heat our homes. Derived gasoline and diesel oil propel our cars, trucks, air- planes. Hydrocarbons are also the feed-stock for practically every man-made material from plastics to pharmaceuticals. What nature is giving us needs, however, to be processed and modified. We will eventually also need to make hydrocarbons ourselves, as our natural resources are depleted. Many of the used processes are acid catalyzed involving chemical reactions proceeding through positive ion intermediates. Consequently, the knowledge of these intermediates and their chemistry is of substantial significance both as fun- damental, as well as practical science. Carbocations are the positive ions of carbon compounds. It was in 1901 that Norris la and Kehrman lb independently discovered that colorless triphe- nylmethyl alcohol gave deep yellow solutions in concentrated sulfuric acid. Triphenylmethyl chloride similarly formed orange complexes with alumi- num and tin chlorides. von Baeyer (Nobel Prize, 1905) should be credited for having recognized in 1902 the salt like character of the compounds for- med (equation 1). -

Introduction to Alkenes and Alkynes in an Alkane, All Covalent Bonds

Introduction to Alkenes and Alkynes In an alkane, all covalent bonds between carbon were σ (σ bonds are defined as bonds where the electron density is symmetric about the internuclear axis) In an alkene, however, only three σ bonds are formed from the alkene carbon -the carbon thus adopts an sp2 hybridization Ethene (common name ethylene) has a molecular formula of CH2CH2 Each carbon is sp2 hybridized with a σ bond to two hydrogens and the other carbon Hybridized orbital allows stronger bonds due to more overlap H H C C H H Structure of Ethylene In addition to the σ framework of ethylene, each carbon has an atomic p orbital not used in hybridization The two p orbitals (each with one electron) overlap to form a π bond (p bonds are not symmetric about the internuclear axis) π bonds are not as strong as σ bonds (in ethylene, the σ bond is ~90 Kcal/mol and the π bond is ~66 Kcal/mol) Thus while σ bonds are stable and very few reactions occur with C-C bonds, π bonds are much more reactive and many reactions occur with C=C π bonds Nomenclature of Alkenes August Wilhelm Hofmann’s attempt for systematic hydrocarbon nomenclature (1866) Attempted to use a systematic name by naming all possible structures with 4 carbons Quartane a alkane C4H10 Quartyl C4H9 Quartene e alkene C4H8 Quartenyl C4H7 Quartine i alkine → alkyne C4H6 Quartinyl C4H5 Quartone o C4H4 Quartonyl C4H3 Quartune u C4H2 Quartunyl C4H1 Wanted to use Quart from the Latin for 4 – this method was not embraced and BUT has remained Used English order of vowels, however, to name the groups -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

Synthesis and Application of Chiral Carbocations

DEGREE PROJECT, INORGANIC CHEMISTRY , SECOND LEVEL STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2015 Synthesis and Application of Chiral Carbocations ANA ALICIA PALES GRAU KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CHE Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my research mentor Prof. Johan Franzén for accepting me in his group and his mentorship during the whole project. His valuable suggestions were very fruitful for the completion of the project. I would also like to thank my research group for their continuous support and valuable inputs. I am grateful to Organic Chemistry department in KTH for providing me the necessary facilities and a great laboratory environment. I must mention my gratitude to my home university Universitat Politècnica de València and my host university KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Erasmus Plus exchange programme of EU. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their continuous encouragements during this whole period. 1 Abstract Asymmetric synthesis is most significant method to generate chiral compounds from prochiral substrates. It usually involves a chiral catalysis, which can be either metal based or organo-catalysis. Both of these systems have their own advantages and disadvantages. In recent times, organocatalysts are gathering widespread attention due to their low toxicity and inexpensive nature. Organocatalysts can replace traditional metal based Lewis acid catalysts in several useful organic transformations like the Diels-Alder reactions. Carbocations are compounds with positively charged carbon atoms and they can activate the substrate by pulling its electrons thus making it more electrophilic. Though carbocations are well-known in literature, they are not well explored in catalysis despite their tremendous potential. -

Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes

05 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes Polyethylene is the most widely used plastic, making up items such as packing foam, plastic bottles, and plastic utensils (top: © Jon Larson/iStockphoto; middle: GNL Media/Digital Vision/Getty Images, Inc.; bottom: © Lakhesis/iStockphoto). Inset: A model of ethylene. KEY QUESTIONS 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? 5.8 How Can Alkynes Be Reduced to Alkenes and 5.2 What Is a Reaction Mechanism? Alkanes? 5.3 What Are the Mechanisms of Electrophilic Additions HOW TO to Alkenes? 5.1 How to Draw Mechanisms 5.4 What Are Carbocation Rearrangements? 5.5 What Is Hydroboration–Oxidation of an Alkene? CHEMICAL CONNECTIONS 5.6 How Can an Alkene Be Reduced to an Alkane? 5A Catalytic Cracking and the Importance of Alkenes 5.7 How Can an Acetylide Anion Be Used to Create a New Carbon–Carbon Bond? IN THIS CHAPTER, we begin our systematic study of organic reactions and their mecha- nisms. Reaction mechanisms are step-by-step descriptions of how reactions proceed and are one of the most important unifying concepts in organic chemistry. We use the reactions of alkenes as the vehicle to introduce this concept. 129 130 CHAPTER 5 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? The most characteristic reaction of alkenes is addition to the carbon–carbon double bond in such a way that the pi bond is broken and, in its place, sigma bonds are formed to two new atoms or groups of atoms. Several examples of reactions at the carbon–carbon double bond are shown in Table 5.1, along with the descriptive name(s) associated with each. -

Determination of Lifetimes of Carbocations in Aqueous Solution

CLASSROOM V Jagannadham Determination of Lifetimes of Carbocations in Aqueous Solution Department of Chemistry Osmania University by azide clock: A Simple Physical-Organic Chemistry Experiment Hyderababd 500 007, India Email: [email protected] A simple and relatively new protocol is described in this article [email protected] for the determination of the lifetimes of carbocations in aqueous solution. A very important intermediate in many organic reactions is the carbocation. As the name implies, carbocation is an organic cation containing a positively charged carbon. It has only a sextet of electrons surrounding the charged carbon and is therefore quite reactive. Originally they were called carbonium ions. The parent + member is the methyl cation (CH3 ). On the strength of kinetic studies, Meerwein and Van Emster [1] suggested the intermediacy of carbocations in solution as earlyas the 1920s. Since then numerous Carbocations new organic compounds were discovered and synthesized. This usually have requires knowledge of the stability and reactivity and the lifetime of lifetimes of the these cations. The history of the field is well documented in the form order of a few of reviews with titles of ‘carbonium ions’ and ‘reactive intermediates’ nanoseconds. [2]. The lifetime of a carbocation is nothing but the reciprocal of the rate coefficient (ks) for its disappearance in a given solvent. If water is the solvent, then we will denote the rate constant by k .Asthe H2O lifetime of the reactive intermediates would normally be in the range of a few nanoseconds, its experimental determination usually needs relatively expensive fast reaction techniques like flow methods, pulse radiolysis or laser flash photolysis methods.