The Importance of Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture and Architecture in Distress – Sarajevo Experiment Doi

Emina Zejnilovic, Erna Husukic Archnet-IJAR, Volume 12 - Issue 1 - March 2018 - (11-35) – Regular Section Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research www.archnet-ijar.net/ -- https://archnet.org/collections/34 CULTURE AND ARCHITECTURE IN DISTRESS – SARAJEVO EXPERIMENT DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v12i1.1289 Emina Zejnilovic, Erna Husukic Keywords Abstract culture; residential This paper attempts to discuss the reciprocal connection architecture; Sarajevo; between culture and architecture as a social product. In doing memory; post-war so, the paper intends to critically engage with the theme of architecture; post-socialist ‘culture’, its impact on residential developments, and its architecture character in the process of recuperation of post-war society in Sarajevo. The development of residential architecture is followed through the four historical periods that had the greatest impact on its formation. Setting the scene to better understand the current built design challenges, post-war, post-socialist culture and architecture are analysed through the lens of T.S. Elliot's (1948) theory on culture. Specifically, the paper refers to the criteria Elliot defined as essential for a culture to survive; Organic Structure, Regional Context and Balance & Unity in Religion. Finally, the paper identifies the main obstacles in the process of cultural transformation of Sarajevo, indicating an urgent need for addressing the issues of cultural and architectural vitality. ArchNet -IJAR is indexed and listed in several databases, including: • Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals • EBSCO-Current Abstracts-Art and Architecture • CNKI: China National Knowledge Infrastructure • DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals • Pro-Quest Scopus-Elsevier • • Web of Science E. -

Partners H E E a T Big See Platform

A C H I T E C T U R E A R C ARCHITECTURE & INTERIOR EVENTS - 3 PRINT - 14 DIGITAL - 18 VENUE - 22 H PACKAGES - 24 T E C T U R E A R C H I T E A R C H I APARTNERSR C H T E BIG SEE PLATFORM 350 MILLION PEOPLE In South-East Europe life is good. It is sometimes really hard, too. There are more nations and languages and religions than in any similarly sized region. People here don’t have much in common. Everything happens too fast. These complexities are as frustrating now as they were life threatening throughout history. With countless rulers and artists and philosophers being born across the region, being creative often meant just managing to stay alive. So when people here talk about disruption, it’s something that happens every day. Outstanding creativity is as normal as the air we breathe, and being native means actually knowing where you belong: to millennia of mind blowing milestones. 19 COUNTRIES Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Hungary, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Serbia, Turkey WHY BIG SEE? BigSEE systematically explores, evaluates, BRANDS exposes promotes and develops business and creative excellence from South-East Volvo / Geberit / Hansgrohe Group / Zumtobel Group / Intra Lighting / Tem / Pirc International / Bauta / Norica / Bauder / Oben- Europe. Auf / Kip / Elementare / Pilon AEC / Helios / Zavarovalnica Triglav / Kalcer / Promat / Doorsolutions / Mizarstvo Košak / KSL Studio / Kult Interier / Maramo / Menerga / -

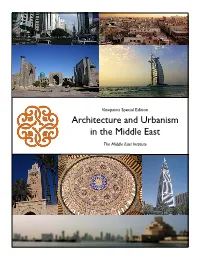

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Arhitektura Slovenije. 4, Vernakularna Arhitektura, Južna Hribovja = Architecture of Slovenia

Naslovnica monografije ARHITEKTURA SLOVENIJE 4 Grafika:Domen Zupančič Oblikovanje :Domen Zupančič,fotografija:Domen Zupančič Datum:25.oktober 2010 Info:[email protected] // 041 795 267 218 mm 218 mm 19 mm hrbet 9 mm zgib 9 mm zgib 25 mm zgib 25 mm zgib 25 mm zgib arhitektura slovenije vernakularna arhitektura,južna hribovja architecture of slovenia borut juvanec 4 vernacular architecture,s houthernills Pregled borut juvanec / Overview 245 mm 245 mm ARHITEKTURA SLOVENIJE * ARCHITECTURE OF SLOVENIA * ARCHITECTURE SLOVENIJE ARHITEKTURA * arhitektura slovenije 4 architecture of slovenia 4 borut juvanec ISBN 978-961-6348-67-6 36,50 € AS4 25 mm zgib 25 mm zgib 25 mm zgib Pregled 27.10.2011 20:29:49 / Overview AS4_1del_rezerva.indd 3 Borut Juvanec ARHITEKTURA SLOVENIJE 4 Vernakularna arhitektura, Južna hribovja ARCHITECTURE OF SLOVENIA 4 Vernacular Architecture, Southern Hills oprema, oblikovanje in prelom Domen Zupančič lektoriranje Karmen Sluga prevajanje Martin Cregeen, angleški teksti Mark Wollrab, nemški izvleček Hélène Erjavec, francoski izvleček Pregled fotografije Borut Juvanec Domen Zupančič predgovor prof. dr. Peter Fister naslovnica spredaj Dolenjska, Dobrava, 2011 naslovnica zadaj Izdelava trniča, Kamnik, 2011 izdala i2 Družba za založništvo, izobraževanje in raziskovanje d.o.o., Ljubljana Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za arhitekturo za založbo Iztok Hafner / tisk Grafika Soča d.o.o. Overview Knjigo je kot znanstveno monografijo podprla Javna agencija za knjigo RS. Natisnjeno 700 izvodov. Prvi natis. Prva izdaja. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 72.031.4(497.4) JUVANEC, Borut Arhitektura Slovenije. 4, Vernakularna arhitektura, južna hribovja = Architecture of Slovenia. [4], Vernacular architecture, Southern hills / Borut Juvanec ; [prevajanje Martin Cregeen, Mark Wollrab, Hélene Erjavec ; fotografije Borut Juvanec, Domen Zupančič; predgovor Peter Fister]. -

Women's Creativity Since the Modern Movement

WOMEN’S CREATIVITY SINCE THE MODERN MOVEMENT (1918-2018): TOWARD A NEW PERCEPTION AND RECEPTION MoMoWo Symposium 2018 Programme and Abstracts of the International Conference Edited by CATERINA FRANCHINI and EMILIA GARDA MoMoWo Symposium 2018. Women’s Creativity since the Modern Movement (1918-2018): Toward a New Perception and Reception. Programme and Abstracts of the International Conference Politecnico di Torino, Campus Lingotto | 13th–16th June 2018, Torino, Italy EDITED BY GRAPHIC DESIGN CONCEPT Caterina Franchini and Emilia Garda Caterina Franchini Emilia Garda MOMOWO SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE POLITO (Turin | Italy) LAYOUT Emilia Garda, Caterina Franchini Pre-press La Terra Promessa ENSILIS IADE (Lisbon | Portugal) TEXTS REVISION Maria Helena Souto Cristiana Chiorino UNIOVI (Oviedo | Spain) ComunicArch Ana Mária Fernández García Caterina Franchini VU (Amsterdam | The Netherlands) MoMoWo Politecnico di Torino - DIST Marjan Groot ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana | Slovenia) PROOFREADING Helena Seražin Cristina Cassavia STUBA (Bratislava | Slovakia) MoMoWo Politecnico di Torino - DISEG Henrieta Moravčíková Caterina Franchini MoMoWo Politecnico di Torino - DIST COORDINATION | SCIENTIFIC SECRETARIAT Caterina Franchini, Politecnico di Torino - DIST PRINTING La Terra Promessa Società Coop. Sociale ONLUS ORGANISING SECRETARIAT Beinasco (Turin, Italy) Cristiana Chiorino, ComunicArch Cristina Cassavia (Assistant), POLITO PUBLISHER Publication of the project MoMoWo - Women’s Politecnico di Torino Creativity since the Modern Movement. This project has been co-funded -

1St Mediterranean Earth Architecture Meeting

EXPERTS WORKSHOP ON THE STUDY AND CONSERVATION OF EARTHEN ARCHITECTURE AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION FINAL REPORT August 20, 2009 Villanovaforru, Sardegna, ITALY, 17-18 March 2009 EXPERTS WORKSHOP ON THE STUDY AND CONSERVATION OF EARTHEN ARCHITECTURE AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION FINAL REPORT Edited by Maddalena Achenza, Claudia Cancino, Mariana Correia, Amila Ferron and Hubert Guillaud Villanovaforru, Sardegna, ITALY, 17-18 March 2009 This work is dedicated to Alejandro Alva Balderrama who for many years has been committed to promoting greater cooperation in the study and conservation of earthen architecture within the Mediterranean region. CREDITS Organizing Institutions: Provincia del Medio Campidano, Sardegna Tourismo, Diparch-Università di Cagliari (UNICA), The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), Escola Superior Gallaecia (ESGallaecia), CRATerre- École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble (CRATerre-ENSAG) Participants: Mauro Bertagnin (Italy), Mohamed Boussalh (Morocco), Claire-Anne de Chazelles (France), Valentina Cristini (for Fernando Vegas and Camilla Mileto, Spain), Maria Fernandes (Portugal), Juana Font (Spain), Bilge Isik (Turkey), Borut Juvanec (Slovenia), Said Kamel (Morocco), Georgia Poursoulis (Greece/France), Ahmed Rashed (Egypt), Vjekoslava Sankovic (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Antonia Theodosiou (Cyprus), Humberto Varum (Portugal) and Leïla el-Wakil (Egypt) Organizing Committee: Maddalena Achenza, Claudia Cancino, Amila -

Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research

Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research SYNCHRONY-CITY: Sarajevo in 5 acts and few intervals Journal: Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Manuscript ID ARCH-05-2019-0125.R1 Manuscript Type: Research Paper Sarajevo, modernist heritage, East-West binary, urban heritage Keywords: destruction, post-conflict society, cross-disciplinary discourse Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Page 1 of 31 Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Fig.1. Photographic record of Neidhardt’s sketch “Urban-architectonic analysis”, exhibited at MoMA New 32 York, 2018 (Photo credits: Vildana Kurtović/Zlata Filipović). 33 34 35 254x191mm (72 x 72 DPI) 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Page 2 of 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Fig.2. The western expansion of the Oriental City, annotated by Lead Author on the “Historijska karta/ “Plan 31 von Sarajevo und Umgebung” (part), Sarajevo: Verlag der Buchhandlung B. Buchwald & Comp., 1900 32 (Source: Program razvoja gradskog jezgra Sarajeva. Sarajevo: Zavod za Planiranje razvoja kantona 33 Sarajevo, 2000, p. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop.Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October Original Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop.Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana / Franchini, Caterina; Garda, EMILIA MARIA; Seražin, Helena. - ELETTRONICO. - (2018), pp. 1-259. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2746292 since: 2020-01-31T10:11:46Z Publisher: ZRC SAZU, France Stele Institute of Art History, Založba ZRC Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference- Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Ljubljana 2018 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Collected by Helena Seražin, Caterina Franchini and Emilia Garda MoMoWo Scientific Committee: POLITO (Turin/Italy) Emilia GARDA, Caterina FRANCHINI IADE-U (Lisbon/Portugal) Maria Helena SOUTO UNIOVI (Oviedo/Spain) Ana María FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA VU (Amsterdam/Netherlands) -

FREISTEHENDE HOLZGLOCKENTÜRME Freestanding Wooden Belfries

Andreja Benko, Borut Juvanec FREISTEHENDE HOLZGLOCKENTÜRME Freestanding Wooden Belfries Regional geprägte Architektur stellt Regional architecture establishes an Wechselwirkungen zwischen Landschaft, interaction between the landscape, Umwelt und Menschen her. Die erhaltenen the environment and the people. freistehenden Holzglockentürme in Ungarn, The preserved freestanding wooden Slowenien und Österreich zeigen das belfries in Hungary, Slovenia and Austria gemeinsame Erbe. document the common heritage. Freilichtmuseum Bad Tatzmannsdorf, Burgenland, Holzglockenturm aus Allersgraben Open-air museum Bad Tatzmannsdorf, Burgenland, wooden belfry from Allersgraben © Benko/Juvanec © Benko/Juvanec In traditionell geprägten ländlichen FREISTEHENDE In traditional rural areas we can see the consistency Gebieten ist die Übereinstimmung HOLZGLOCKENTÜRME between the landscape and the built environment. zwischen der Landschaft und der Borut Juvanec2 behauptet, dass re- This environment shows us heritage objects which gebauten Umwelt sichtbar. Sie zeigt gionale traditionelle Architektur were built as homes, animal shelters, storage objects uns Baukultur in Form von Häusern, einfach, in den Dimensionen relativ and structures meant for the community. These ob- Stallungen, Lagern und Gebäuden, klein, aber auch zweckmäßig ist – jects are vernacular architecture and it is typical that die für die Allgemeinheit gedacht und von Personen errichtet wurde, they were always built by local master craftsmen. They waren. Diese regionale traditionelle die keine „geschulten“ Baumeister were created from the needs of the local inhabitants, Architektur wurde meist von örtlichen waren. Auch der Bauherr war nicht their life and work, built of local materials and with the Handwerksmeistern errichtet. Form ausgebildet, hat die großartigsten thoughtful logic based upon experience, weather con- und Funktion der Bauten sind aus den Architekturwerke der Welt nie gese- ditions, landscape and materials. -

Why Preserve Vernacular Architecture, and How?

Why preserve Vernacular Architecture, and how? he Vemacular Architecture of Slovenia is a.basic specialist and popu lar work on monuments of this kind by specialists in ethnology and con T servation. Publications by architects, art historians and ethnologists have hither to concentrated on the development ofVemacular Architecture and on typological reviews, but there ha s been no systematic review of properly maintained and renovated publicly accessible monuments ofVernac ular Architecture, compiled from the point of view of the preservation of the natural and cultural heritage. The introduction aims to present preservation activities, their main tasks and the specific nature of the preservation ofVernacular Architecture. The bulk of the publication consists of a presenta ti on of selected buildings and area s ofVernacular Architecture with an emphasis on reviewing their significance and the preservation works undertaken. Sin ce surveys of the most important aspects of the ethnological heritage and protected ethnological monu ments are published exclusively according to professional criteria, we have insisted on the existing basic criterion of selection with the primary aim of promotion in the broader sense. Criteria of the degree of pres ervation and historic importance have also been observed. The immovable ethnological heritage of the countryside, or simply "Vernacular Architecture", consists of professionally selected and de fined rural settlements, market towns, homesteads, residential and farm buildings and also alllandscape planning rela ted to the buildings. This includes the culturallandscape, embracing all human activity in nature, ranging from construction to the cultivation and exploitation ofland. The value of our Vernacular Architecture cannot be judged according to selected buildings from other parts of the world, which do not exist in Slovenia. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

The Iranian Embassy in Washington, DC

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Architecture of Poetry: The Iranian Embassy in Washington, D.C. A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Architecture, 2007 In the School of Architecture and Interior Design College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning Mercedeh Namei B.S.Arch., University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Jay Chatterjee Committee Members: Aarati Kanekar Vincent Sansalone Abstract 3 An embassy is a symbol of unique cultural, social and political aspects of a specific country. Historically it becomes a place for a country’s representative(s) to communicate in a civilized and acceptable manner. Communications among embassies have traditionally been a great resource for international diplomacy that promotes peace and friendship. An embassy is an office building that specializes in diplomatic relationships and a great representative for one culture. Presenting a culture requires multifaceted revelation of its aspects. In the project Architecture of Poetry was derived from Persian poetry. In order to understand Persian culture and its classical poetry, the methodology includes discussion of Ferdosi’s Shähnmeh (The Epic of Kings). Persian poetry is deeply rooted in its history and culture. It was developed through centuries of repetition and practice. Understanding Persian poetry reveals layers of history, culture and traditions. It requires understanding structure, order and the metaphorical foundation of poetry as well as the reasons behind lyrics, meanings and characters.