A Note on the Origins of Hali's Musaddas-E Madd-O Jazr-E Islām

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

61 in This Book, the Author Has Given the Hfe Sketch of the Distinguish Personahties, Who Supported the Augarh Movement and Made

61 In this book, the author has given the Hfe sketch of the distinguish personahties, who supported the AUgarh Movement and made efforts for the betterment of the MusHm Community. The author highlighting the importance of the Aligarh Muslim University said that "it is the most prestigious intellectual and cultural centre of Indian Muslims". He also explained in this book that Hindus easily adopted the western education. As for Hindus, the advent of the Britishers and their emergence as the rulers were just a matter of change from one master to another. For them, the Britishers and Muslims were both conquerors. But for the Muslims it was a matter of becoming ruled instead of the ruler. Naqvi, Noorul Hasan (2001) wrote a book in Urdu entitled "Mohammadan College Se Muslim University Tak (From Mohammadan College to Muslim University)".^^ In this book he wrote in brief about the life and works of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, He gave a brief description about the supporters of Sir Syed and Aligarh Movement such as Mohsin-ul-Mulk, Viqar-ul-Mulk, Altaf Husain Hali, Maulana Shibli Nomani, Moulvi Samiullah Khan, Jutice Mahmud, Raja Jai Kishan Das and Maulvi ZakauUah Khan, etc. The author also wrote about the Aligarh Movement, the Freedom Movement and the educational planning of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. A historical development of AMU has also been made. The author has also given in brief about the life of some of the important benefactors of the university such as His Highness Sir Agha Khan, Her Majestry Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum, His Holiness Maharaja Mohammad Ali Khan of . -

The Musaddas of Hali

Al-Ayyam-10 The Musaddas of Hali The Musaddas of Hali A Reinterpretation Syed Munir Wasti * Abstract: Hali’s Musaddas has long been treated as an elegy on Muslim greatness. This approach is narrow and restricts the poem’s great revolutionary character. In this essay, the Musaddas is seen as a poetic charter for the liberation of Muslims from foreign yoke and their assertion as a separate religious entity. The Musaddas has to be seen as the herald of national movement to assert Muslim identity thereby leading logically to the demand for a separate Muslim state. The opinions of various critics are cited in support of this thesis. * Prof. (R), Dr. Syed Munir Wasti, Dept. of English, University of Karachi 6 PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Al-Ayyam-10 The Musaddas of Hali Whereas there has been a revival of interest in Hali’s famous poem titled Musaddas-i-madd-u jazr-i-Islam, commonly called the Musaddas – as evidenced by two [1] recent translations, i.e., that by Christopher Shackle and Jawed Majeed 1997 [called ‘Shackle-Majeed’ henceforth] and the one by Syeda Saiyidain Hameed [2003], this has not been accompanied by a concomitant trend to hail Hali as a precursor of Islamic renaissance or revival in South Asia. There appears to be a sinister attempt to tone down his revolutionary or revivalist role and even to show him as a docile acceptor of the imperial status quo. The two translations have been reviewed by the present writer in Pakistan Perspectives [vol. 9, no.2, July-December 2004; vol. -

In Quest of Jinnah

Contents Acknowledgements xiii Preface xv SHARIF AL MUJAHID Introduction xvii LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT, SHARIF AL MUJAHID Publisher's Note xxi AMEENA SAIYID SECTION 1: ORIGINAL ESSAYS ON JINNAH 1 1. Mohammad Ali Jinnah: One of the Greatest Statesmen of the Twentieth Century 2 STANLEY WOLPERT 2. Partition and the Birth of Pakistan 4 JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH 3. World of His Fathers 7 FOUAD AJAMI 4. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 12 LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT 5. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: A Historian s Perspective 17 S.M. BURKE 6. Jinnah: A Portrait 19 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 7. Quaid-i-Azam's Personality and its Role and Relevance in the Achievement of Pakistan 32 SIKANDAR HAYAT 8. Mohammad Ali Jinnah 39 KULDIP NAYAR 9. M.A. Jinnah: The Official Biography 43 M.R. KAZIMI 10. The Official Biography: An Evaluation 49 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 11. Inheriting the Raj: Jinnah and the Governor-Generalship Issue 59 AYESHA JALAL 12. Constitutional Set-up of Pakistan as Visualised by Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 76 S. SHARIFUDDIN PIRZADA 13. Jinnah—Two Perspectives: Secular or Islamic and Protector General ot Minorities 84 LIAQUAT H. MERCHANT 14. Jinnah on Civil Liberties 92 A.G. NOORANl 15. Jinnah and Women s Emancipation 96 SHARIF AL MUJAHID 16. Jinnah s 'Gettysburg Address' 106 AKBAR S. AHMED 17. The Two Saviours: Ataturk and Jinnah 110 MUHAMMAD ALI SIDDIQUI 18. The Quaid and the Princely States of India 115 SHAHARYAR M. KHAN 19. Reminiscences 121 JAVID IQBAL 20. Jinnah as seen by Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah,Aga Khan III 127 LIAQUAT H. -

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares Unclaimed Unclaimed S.No FOLIO NAME CNIC / NTN Address Shares Dividend 22, BAHADURABADROAD NO.2, BLOCK-3KARACHI-5 1 38 MR. MOHAMMAD ASLAM 00000-0000000-0 5,063 558/5, MOORE STREETOUTRAM ROADKARACHI 2 39 MR. MOHAMMAD USMAN 00000-0000000-0 5,063 FLAT NO. 201, SAMAR CLASSIC,KANJI TULSI DAS 3 43 MR. ROSHAN ALI 42301-1105360-7 STREET,PAKISTAN CHOWK, KARACHI-74200.PH: 021- 870 35401984MOB: 0334-3997270 34, AMIL COLONY NO.1SHADHU HIRANAND 4 47 MR. AKBAR ALI BHIMJEE 00000-0000000-0 ROADKARACHI-5. 5,063 PAKISTAN PETROLEUM LIMITED3RD FLOOR, PIDC 5 48 MR. GHULAM FAREED 00000-0000000-0 HOUSEDR. ZIAUDDIN AHMED ROADKARACHI. 756 C-3, BLOCK TNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 6 63 MR. FAZLUR RAHMAN 00000-0000000-0 7,823 C/O. MUMTAZ SONS11, SIRAJ CLOTH 7 68 MR. AIJAZUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 MARKETBOMBAY BAZARKARACHI. 5,063 517-B, BLOCK 13FEDERAL 'B' AREAKARACHI. 8 72 MR. S. MASOOD RAZA 00000-0000000-0 802 93/10-B, DRIGH ROADCANTT BAZARKARACHI-8. 9 81 MR. TAYMUR ALI KHAN 00000-0000000-0 955 BANK SQUARE BRANCHLAHORE. 10 84 THE BANK OF PUNJAB 00000-0000000-0 17,616 A-125, BLOCK-LNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI-33. 11 127 MR. SAMIULLAHH 00000-0000000-0 5,063 3, LEILA BUILDING, ABOVE UBLARAMBAGH ROAD, 12 150 MR. MUQIMUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 PAKISTAN CHOWKKARACHI-74200. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT. COLLEGE FOR 13 152 MRS. KARIMA ABDUL RAHIM 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT COLLEGE FOR 14 153 DR. ABDUL RAHIM GANDHI 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Picture of Muslim Politics in India Before Wavell's

Muhammad Iqbal Chawala PICTURE OF MUSLIM POLITICS IN INDIA BEFORE WAVELL’S VICEROYALTY The Hindu-Muslim conflict in India had entered its final phase in the 1940’s. The Muslim League, on the basis of the Two-Nation Theory, had been demanding a separate homeland for the Muslims of India. The movement for Pakistan was getting into full steam at the time of Wavell’s arrival to India in October 1943 although it was opposed by an influential section of the Muslims. This paper examines the Muslim politics in India and also highlights the background of their demand for a separate homeland. It analyzes the nature, programme and leadership of the leading Muslim political parties in India. It also highlights their aims and objectives for gaining an understanding of their future behaviour. Additionally, it discusses the origin and evolution of the British policy in India, with special reference to the Muslim problem. Moreover, it tries to understand whether Wavell’s experiences in India, first as a soldier and then as the Commander-in-Chief, proved helpful to him in understanding the mood of the Muslim political scene in India. British Policy in India Wavell was appointed as the Viceroy of India upon the retirement of Lord Linlithgow in October 1943. He was no stranger to India having served here on two previous occasions. His first-ever posting in India was at Ambala in 1903 and his unit moved to the NWFP in 1904 as fears mounted of a war with 75 76 [J.R.S.P., Vol. 45, No. 1, 2008] Russia.1 His stay in the Frontier province left deep and lasting impressions on him. -

The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ) https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/1.1.2 Vol. 1, No. 1, (January-June) 2017, 71-82 https://www.ideapublishers.org/lassij __________________________________________________________________ The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan Syed Mukarram Shah Gilani1*, Asif Salim1-2 and Noor Ullah Khan1-3 1. Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar Pakistan. 2. Department of Political Science, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia USA. 3. Department of Civics-cum-History, FG College Nowshera Cantt., Pakistan. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract The partition of Indian sub-continent in 1947 was a historic event surrounded by many controversies and issues. Some of those ended up with the passage of time while others were kept alive and orchestrated. Besides numerous problems for the newly born state of Pakistan, one such controversy was about the Muhajirs (immigrants) who were settled in Karachi. The paper analyses the factors that brought the relation between the native Sindhis and Muhajirs to such an impasse which resulted in the growth of conspiracy theories, division among Sindhis; subsequently to the demand of Muhajir Suba (Province); target killings, extortion; and eventually to military clean-up operation in Karachi. The paper also throws light on the twin simmering problems of native Sindhis and Muhajirs. Besides, the paper attempts to answer the question as to why the immigrants could not merge in the native Sindhis despite living together for so long and why the native Sindhis remained backward and deprived. Finally, the paper aims at bringing to limelight the role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). -

Gulshan Zubair Under the Supervision of Dr. Parwez Nazir

ROLE OF MUHAMMADAN EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCE IN THE EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL UPLIFTMENT OF INDIAN MUSLIMS ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History by Gulshan Zubair Under the Supervision of Dr. Parwez Nazir Center of Advanced Study Department of History ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2015 ABSTARACT Since the beginning of the 19th century the East India Company had acquired some provinces and had laid down a well planned system of education which was unacceptable to the Muslims. For its being modern and progressive Dr. W.W. Hunter in his book ‘Indian Musalmans’ accepted that the newly introduced system of education opposed the conditions and patterns prevalent in the Muslim Community. It did not suit to the general Muslim masses and there was a hatred among its members. The Muslims did not cooperate with the British and kept them aloof from the Western Education. Muslim community also felt that the education of the Christian which was taught in the Government school would convert them to Christianity. This was also a period of transition from medievalism to modernism in the history of the Indian Muslims. Sir Syed was quick to realize the Muslims degeneration and initiated a movement for the intellectual and cultural regeneration of the Muslim society. The Aligarh Movement marked a beginning of the new era, the era of renaissance. It was not merely an educational movement but an all pervading movement covering the entire extent of social and cultural life. The All India Muslim Educational conference (AIMEC) is a mile stone in the journey of Aligarh Movement and the Indian Muslims towards their educational and cultural development. -

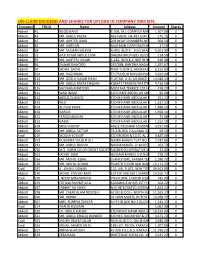

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy, Pakistan

QBAL EVIEW I R Journal of the Iqbal Academy, Pakistan October 2004 Editor Muhammad Suheyl Umar IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN Title : Iqbal Review (October 2004) Editor : Muhammad Suheyl Umar Publisher : Iqbal Academy Pakistan City : Lahore Year : 2004 Classification (DDC) : 105 Classification (IAP) : 8U1.66V12 Pages : 165 Size : 14.5 x 24.5 cm ISSN : 0021-0773 Subjects : Iqbal Studies : Philosophy : Research IQBAL CYBER LIBRARY (www.iqbalcyberlibrary.net) Iqbal Academy Pakistan (www.iap.gov.pk) 6th Floor Aiwan-e-Iqbal Complex, Egerton Road, Lahore. Table of Contents Volume: 45 Iqbal Review: October 2004 Number: 4 1. TIME, SPACE, AND THE OBJECTIVITY OF ETHICAL NORMS: THE TEACHINGS OF IBN AL-‘ARABI ........................................................................................ 6 2. THE IDEA OF CREATION IN IQBAL’S PHLOSOPHY OF RELIGION .............. 24 3. FREEDOM AND LAW ........................................................................................................... 34 4. THE UNIVERSAL APPEAL OF IQBAL’S VERSE ......................................................... 49 5. ISLAMIC MODERNITY AND THE DESIRING SELF: MUHAMMAD IQBAL AND THE POETICS OF NARCISSISM* ........................................................................... 66 6. …ÁIKMAT I MARA BA MADRASAH KEH BURD?: THE INFLUENCE OF SHIRAZ SCHOOL ON THE INDIAN SCHOLARS ....................................................... 98 7. IQBAL STUDIES IN BENGALI LITERATURE ........................................................... 115 8. THE BUYID DOMINATION AS THE HISTORICAL -

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES and MONUMENTS in SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED by the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND MONUMENTS IN SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1. Runs of old city at Badin, Badin Dadu District 2. Tomb of Yar Muhammad Khan kalhora and its adjoining Masjid near khudabad, Dadu. 3. Jami Masjid, Khudabad, Dadu. 4. Rani Fort Kot, Dadu. 5. Amri, Mounds, Dadu. 6. Lakhomir-ji-Mari, Deh Nang opposite Police outpost, Sehwan, Dadu. 7. Damb Buthi, Deh Narpirar at the source of the pirari (spring), south of Jhangara, Sehwan, Dadu. 8. Piyaroli Mari, Deh Shouk near pir Gaji Shah, Johi, Dadu. 9. Ali Murad village mounds, Deh Bahlil Shah, Johi, Dadu. 10. Nasumji Buthi, Deh Karchat Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 11. Kohtrass Buthi, Deh Karchat about 8 miles south-west of village of Karchat on road from Thana Bula Khan to Taung, Dadu. 12. Othamjo Buthi Deh Karchat or river Baran on the way from the Arabjo Thano to Wahi village north-west of Bachani sandhi, Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 13. Lohamjodaro, Deh Palha at a distance of 30 chains from Railway Station but not within railway limits, Dadu. 14. Pandhi Wahi village mounds, Deh Wahi, Johi, Dadu. 15. Sehwan Fort, Sehwan, Dadu. 16. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. 17. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. Hyderabad District 18. Tomb of Ghulam Shah Kalhora, Hyderabad. 19. Boundary Wall of Pucca Fort, Hyderabad. 20. Old office of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 21. Tajar (Treasury) of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 22. Tomb of Ghulam Nabi Khan Kalhora, Hyderabad. 23. Buddhist Stupa, (Guja) a few miles from Tando Muhammad Khan, Hyderabad. 24. -

1 Mohajir Qaumi Movement (Mqm) (A Linguistic And

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 1 No. 1 January 2013 MOHAJIR QAUMI MOVEMENT (MQM) (A LINGUISTIC AND RACIAL POLITICAL PARTY1979-1988) ABDUL QADIR MUSHTAQ Faisalabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT MQM is a political party which plays an important role in the politics of Pakistan. It is trying to increase its influence in all provinces of Pakistan and for this purpose branches are being established in the various cities if Pakistan. It claims to be the representative of the deprive people of all Pakistan. This paper presents the study of MQM with special reference to its creation and what were the factors behind its creation. This study will also disclose the relation of MQM and military dictator Zia. What is the main dispute between the religious sections and MQM, Punjabi and MQM, Pushtoon and MQM? How the agencies played role in strengthening the unity and harmony among the Mahajirs? Is MQM politics based on regionalism and racialism? KEYWORDS: MQM, Pakistan Politics, Mahajirs, INTRODUCTION With the partition of India and Pakistan, a large number of Muslims migrated from India to Pakistan with great difficulties and losses. The Muslims were murdered and killed by the Hindus on their travel to Pakistan. These people had the different languages and cultures. They settled in the various cities of Pakistan but most of them settled in Sindh. The settlement of the Mahajirs in various districts of Sindh can be seen: 1 Abdul Qadir Mushtaq District Refugee Urban Rural Urdu M. Tongue Population Dadu 20720 9194 11526 16589 Hyderabad 205641