“Go Off and Do Something Wonderful” F O U R Stories F Rom the Li F E O F R Obert N Oyce // B Y L Eslie B Erlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Is a Microprocessor Not a Microprocessor? the Industrial Construction of Semiconductor Innovation I

Ross Bassett When is a Microprocessor not a Microprocessor? The Industrial Construction of Semiconductor Innovation I In the early 1990s an integrated circuit first made in 1969 and thus ante dating by two years the chip typically seen as the first microprocessor (Intel's 4004), became a microprocessor for the first time. The stimulus for this piece ofindustrial alchemy was a patent fight. A microprocessor patent had been issued to Texas Instruments, and companies faced with patent infringement lawsuits were looking for prior art with which to challenge it. 2 This old integrated circuit, but new microprocessor, was the ALl, designed by Lee Boysel and used in computers built by his start-up, Four-Phase Systems, established in 1968. In its 1990s reincarnation a demonstration system was built showing that the ALI could have oper ated according to the classic microprocessor model, with ROM (Read Only Memory), RAM (Random Access Memory), and I/O (Input/ Output) forming a basic computer. The operative words here are could have, for it was never used in that configuration during its normal life time. Instead it was used as one-third of a 24-bit CPU (Central Processing Unit) for a series ofcomputers built by Four-Phase.3 Examining the ALl through the lenses of the history of technology and business history puts Intel's microprocessor work into a different per spective. The differences between Four-Phase's and Intel's work were industrially constructed; they owed much to the different industries each saw itselfin.4 While putting a substantial part ofa central processing unit on a chip was not a discrete invention for Four-Phase or the computer industry, it was in the semiconductor industry. -

Semiconductor Industry Social Media Review

Revealed SOCIAL SUCCESS White Paper Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2, September 3, 2014 The contents of this White Paper are protected by copyright and must not be reproduced without permission © 2014 Publitek Ltd. All rights reserved Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 SOCIAL SUCCESS Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Report title OVERVIEW This time, in the interest of We’ve combined quantitative balance, we have decided to and qualitative measures to This report is an update to our include these companies - Intel, reach a ranking for each original white paper from channel. Cross-channel ranking Samsung, Sony, Toshiba, Nvidia led us to the overall index. September 2013. - as well as others, to again analyse the following channels: As before, we took a company’s Last time, we took the top individual “number semiconductor companies 1. Blogs score” (quantitative measure) (according to gross turnover - 2. Facebook for a channel, and multiplied main source: Wikipedia), of this by its “good practice score” 3. Google+ which five were ruled out due (qualitative measure). 4. LinkedIn to the diversity of their offering 5. Twitter The companies were ranked by and the difficulty of segmenting performance in each channel. 6. YouTube activity relating to An average was then taken of semiconductors. ! their positions in each to create the final table. !2 Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 Due to the instantaneous nature of social media, this time we decided to analyse a narrower time frame, and picked a single month - August 2014. -

Outline ECE473 Computer Architecture and Organization • Technology Trends • Introduction to Computer Technology Trends Architecture

Outline ECE473 Computer Architecture and Organization • Technology Trends • Introduction to Computer Technology Trends Architecture Lecturer: Prof. Yifeng Zhu Fall, 2009 Portions of these slides are derived from: ECE473 Lec 1.1 ECE473 Lec 1.2 Dave Patterson © UCB Birth of the Revolution -- What If Your Salary? The Intel 4004 • Parameters – $16 base First Microprocessor in 1971 – 59% growth/year – 40 years • Intel 4004 • 2300 transistors • Initially $16 Æ buy book • Barely a processor • 3rd year’s $64 Æ buy computer game • Could access 300 bytes • 16th year’s $27 ,000 Æ buy cacar of memory • 22nd year’s $430,000 Æ buy house th @intel • 40 year’s > billion dollars Æ buy a lot Introduced November 15, 1971 You have to find fundamental new ways to spend money! 108 KHz, 50 KIPs, 2300 10μ transistors ECE473 Lec 1.3 ECE473 Lec 1.4 2002 - Intel Itanium 2 Processor for Servers 2002 – Pentium® 4 Processor • 64-bit processors Branch Unit Floating Point Unit • .18μm bulk, 6 layer Al process IA32 Pipeline Control November 14, 2002 L1I • 8 stage, fully stalled in- cache ALAT Integer Multi- Int order pipeline L1D Medi Datapath RF @3.06 GHz, 533 MT/s bus cache a • Symmetric six integer- CLK unit issue design HPW DTLB 1099 SPECint_base2000* • IA32 execution engine 1077 SPECfp_base2000* integrated 21.6 mm L2D Array and Control L3 Tag • 3 levels of cache on-die totaling 3.3MB 55 Million 130 nm process • 221 Million transistors Bus Logic • 130W @1GHz, 1.5V • 421 mm2 die @intel • 142 mm2 CPU core L3 Cache ECE473 Lec 1.5 ECE473 19.5mm Lec 1.6 Source: http://www.specbench.org/cpu2000/results/ @intel 2006 - Intel Core Duo Processors for Desktop 2008 - Intel Core i7 64-bit x86-64 PERFORMANCE • Successor to the Intel Core 2 family 40% • Max CPU clock: 2.66 GHz to 3.33 GHz • Cores :4(: 4 (physical)8(), 8 (logical) • 45 nm CMOS process • Adding GPU into the processor POWER 40% …relative to Intel® Pentium® D 960 When compared to the Intel® Pentium® D processor 960. -

1. Definition of Computers Technically, a Computer Is a Programmable Machine

1. Definition of computers Technically, a computer is a programmable machine. This means it can execute a programmed list of instructions and respond to new instructions that it is given. 2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of using computer? Advantages are : communication is improved, pay bill's online, people have access to things they would not have had before (for instance old people who cannot leave the house they can buy groceries online) Computers make life easier. The disadvantages are: scams, fraud, people not going out as much, we do not yet know the effects of computers and pregnancy or the emissions that computers make,. bad posture from sitting too long at a desk, repetitive strain injuries and the fact that most organizations expect everyone to own a computer. Year 1901 The first radio message is sent across the Atlantic Ocean in Morse code. 1902 3M is founded. 1906 The IEC is founded in London England. 1906 Grace Hopper is born December 9, 1906. 1911 Company now known as IBM on is incorporated June 15, 1911 in the state of New York as the Computing - Tabulating - Recording Company (C-T-R), a consolidation of the Computing Scale Company, and The International Time Recording Company. 1912 Alan Turing is born June 23, 1912. 1912 G. N. Lewis begins work on the lithium battery. 1915 The first telephone call is made across the continent. 1919 Olympus is established on October 12, 1919 by Takeshi Yamashita. 1920 First radio broadcasting begins in United States, Pittsburgh, PA. 1921 Czech playwright Karel Capek coins the term "robot" in the 1921 play RUR (Rossum's Universal Robots). -

Class-Action Lawsuit

Case 3:20-cv-00863-SI Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 1 of 279 Steve D. Larson, OSB No. 863540 Email: [email protected] Jennifer S. Wagner, OSB No. 024470 Email: [email protected] STOLL STOLL BERNE LOKTING & SHLACHTER P.C. 209 SW Oak Street, Suite 500 Portland, Oregon 97204 Telephone: (503) 227-1600 Attorneys for Plaintiffs [Additional Counsel Listed on Signature Page.] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF OREGON PORTLAND DIVISION BLUE PEAK HOSTING, LLC, PAMELA Case No. GREEN, TITI RICAFORT, MARGARITE SIMPSON, and MICHAEL NELSON, on behalf of CLASS ACTION ALLEGATION themselves and all others similarly situated, COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL v. INTEL CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation, Defendant. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATION COMPLAINT Case 3:20-cv-00863-SI Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 2 of 279 Plaintiffs Blue Peak Hosting, LLC, Pamela Green, Titi Ricafort, Margarite Sampson, and Michael Nelson, individually and on behalf of the members of the Class defined below, allege the following against Defendant Intel Corporation (“Intel” or “the Company”), based upon personal knowledge with respect to themselves and on information and belief derived from, among other things, the investigation of counsel and review of public documents as to all other matters. INTRODUCTION 1. Despite Intel’s intentional concealment of specific design choices that it long knew rendered its central processing units (“CPUs” or “processors”) unsecure, it was only in January 2018 that it was first revealed to the public that Intel’s CPUs have significant security vulnerabilities that gave unauthorized program instructions access to protected data. 2. A CPU is the “brain” in every computer and mobile device and processes all of the essential applications, including the handling of confidential information such as passwords and encryption keys. -

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland Note: Thank you to Kathy DiPhilippo, Executive Director/Curator of the South Portland Historical Society and Judith Borelli, Governmental Relations of Texas Inc. for providing some of the information for this timeline below. Fairchild Semiconductor 1962 Fairchild Semiconductor (a subsidiary of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp.) opened in the former Boland's auto building (present day Back in Motion) at 185 Ocean Street in June of 1962. They were there only temporarily, as the Western Avenue building was still being constructed. 1963 Fairchild Semiconductor moves to Western Avenue in February 1963. 1979 Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp. is acquired/merged with Schlumberger, Ltd. (New York) for $363 million. 1987 Schlumberger, Ltd. sells its Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. subsidiary to National Semiconductor Corp. for $122 million. 1997 National Semiconductor sells the majority ownership interest in Fairchild Semiconductor to an investment group (made up of Fairchild managers, including Kirk Pond, and Citcorp Venture Capital Ltd.) for $550 million. Added Corporate Campus on Running Hill Road. 1999 In an initial public offering in August 1999, Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. becomes a publicly traded corporation on the New York Stock Exchange. 2016 Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. is acquired by ON Semiconductor for $2.4 billion. National Semiconductor 1987 National Semiconductor acquires Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. from Schlumberger, Ltd. for $122 million. 1995 National Semiconductor breaks ground on new 200mm factory in December 1995. 1996 National Semiconductor announces plans for a $600 million expansion of its facilities in South Portland; construction of a new wafer fabrication plant begins. 1997 Plant construction for 200mm factory completed and production starts. -

Readingsample

Springer Series in Materials Science 106 Into The Nano Era Moore's Law Beyond Planar Silicon CMOS Bearbeitet von Howard Huff 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. xxviii, 348 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 540 74558 7 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 725 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Technik > Elektronik > Mikroprozessoren Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. 2 The Economic Implications of Moore’s Law G.D. Hutcheson 2.1 Introduction One hundred nanometers is a fundamental technology landmark. It is the demarca- tion point between microtechnology and nanotechnology. The semiconductor indus- try crossed it just after the second millennium had finished. In less than 50 years, it had come from transistors made in mils (one-thousandth of an inch or 25.4 mi- crons); to integrated circuits which were popularized as microchips; and then as the third millennium dawned, nanochips. At this writing, nanochips are the largest single sector of nanotechnology. This, in spite of many a nanotechnology expert’s predic- tion that semiconductors would be dispatched to the dustbin of science – where tubes and core memory lie long dead. Classical nanotechnologists should not feel any dis- grace, as pundits making bad predictions about the end of technology progression go back to the 1960s. Indeed, even Gordon Moore wondered as he wrote his clas- sic paper in 1965 if his observation would hold into the 1970s. -

Nanoscale Transistors Fall 2006 Mark Lundstrom Electrical

SURF Research Talk, June 16, 2015 Along for the Ride – reflections on the past, present, and future of nanoelectronics Mark Lundstrom [email protected] Electrical and Computer Engineering Birck Nanotechnology Center Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana USA Lundstrom June 2015 what nanotransistors have enabled “If someone from the 1950’s suddenly appeared today, what would be the most difficult thing to explain to them about today?” “I possess a device in my pocket that is capable of assessing the entirety of information known to humankind.” “I use it to look at pictures of cats and get into arguments with strangers.” Curious, by Ian Leslie, 2014. transistors The basic components of electronic systems. >100 billion transistors Lundstrom June 2015 transistors "The transistor was probably the most important invention of the 20th Century, and the story behind the invention is one of clashing egos and top secret research.” -- Ira Flatow, Transistorized! http://www.pbs.org/transistor/ Lundstrom June 2015 “The most important moment since mankind emerged as a life form.” Isaac Asimov (speaking about the “planar process” used to manufacture ICs - - invented by Jean Hoerni, Fairchild Semiconductor, 1959). IEEE Spectrum Dec. 2007 Lundstrom June 2015 Integrated circuits "In 1957, decades before Steve Jobs dreamed up Apple or Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook, a group of eight brilliant young men defected from the Shockley Semiconductor Company in order to start their own transistor business…” Silicon Valley: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/silicon/ -

UW EE Professional Masters Program To

Electrical Engineering Fall 2007 The ntegrator In this issue UW EE Professional Masters Program To Dean’s Message 2 Chair’s Message 2 Commence In 2008 New Faculty 3 UW EE is pleased to announce the availability of an evening professional master’s degree Damborg Retires 3 in electrical engineering. The Professional Masters Program (PMP) is designed primarily Parviz Wins TR35 4 for the working professional employed locally in the Puget Sound to allow students the flexibility of working while pursuing an MSEE. Classes will be offered in the evening on In Memory 4 the Seattle campus and are scheduled to begin winter quarter 2008. “For the first time, Student Awards 5 the UW MSEE degree will be available in an evening format,” says Professor and Associ- New Scholarship 5 ate Chair for Education, Jim Ritcey. “The addition of an MS degree on your resume can be critical when seeking new opportunities.” Alumni Profile 6 Class Notes 7 Based on a comprehensive marketing survey carried out by UW Office of Educational Outreach, the PMP will initially focus on four curriculum areas. These include Controls, Electromagnetics, Signal and Image Process- Earn a MSEE In the Evening ing, and Wireless Communications. As the program matures, additional topic areas will Considered getting a MSEE but can’t quit your job? UW be available to PMP students. The program EE’s Professional Master’s Program allows you to keep your will meet the same high standard as the full- knowledge up-to-date in this fast moving field by working time degree, although the course content will vary. -

Intuitive Analog Circuit Design

Chapter 1 Introduction MTThMarc T. Thompson, PhDPh.D. Thompson Consulting, Inc. 9 Jacob Gates Road Harvard, MA 01451 Phone: (978) 456-7722 Fax: (240) 414-2655 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.thompsonrd.com Slides to accomppyany Intuitive Analoggg Circuit Design byyp Marc T. Thompson © 2006-2008, M. Thompson Analog Design is Not Dead • The world is analog •…(well, until we talk about Schrodinger) Introduction 2 Partial Shopping List of Analog Design • Analogg,,p filters: Discrete or ladder filters, active filters, switched capacitor filters. • Audio amplifiers: Power op-amps, output (speaker driver) stages • Oscillators: Oscillators, phase-locked loops, video demodulation • Device fabrication and device physics: MOSFETS, bipolar transistors, diodes, IGBTs,,,, SCRs, MCTs, etc. • IC fabrication: Operational amplifiers, comparators, voltage references, PLLs, etc • Analog to digital interface: A/D and D/A, voltage references • Radio frequency circuits: RF amplifiers, filters, mixers and transmission lines; cable TV • Controls: Control system design and compensation, servomechanisms, speed controls • Power electronics: This field requires knowledge of MOSFET drivers, control syyg,y,stem design, PC board layout, and thermal and magg;netic issues; motor drivers; device fabrication of transistors, MOSFETs (metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors), IGBTs (insulated gate bipolar transistors), SCRs (silicon- controlled rectifiers) • Medical electronics: instrumentation (EKG, NMR), defibrillators, implanted medical devices • Simulation: SPICE and other circuit simulators • PC board layout: This requires knowledge of inductance and capacitive effects, grounding, shielding and PC board design rules. Introduction 3 Lilienfeld Patent (c. 1930) 4 Introduction 1st Bipolar Transistor (c. 1948) • Point contact transistor , demonstrated December 23, 1947 at Bell Labs (Shockley, Bardeen and Brattain) Reference: Probir K. -

Transistors to Integrated Circuits

resistanc collectod ean r capacit foune yar o t d commercial silicon controlled rectifier, today's necessarye b relative .Th e advantage lineaf so r thyristor. This later wor alss kowa r baseou n do and circular structures are considered both for 1956 research [19]. base resistanc r collectofo d an er capacity. Parameters, which are expected to affect the In the process of diffusing the p-type substrate frequency behavior considerede ar , , including wafer into an n-p-n configuration for the first emitter depletion layer capacity, collector stage of p-n-p-n construction, particularly in the depletion layer capacit diffusiod yan n transit redistribution "drive-in" e donophasth f ro e time. Finall parametere yth s which mighe b t diffusion at higher temperature in a dry gas obtainabl comparee ear d with those needer dfo ambient (typically > 1100°C in H2), Frosch a few typical switching applications." would seriously damag r waferseou wafee Th . r surface woul e erodedb pittedd an d r eveo , n The Planar Process totally destroyed. Every time this happenee dth s e apparenlosexpressiowa th s y b tn o n The development of oxide masking by Frosch Frosch' smentiono t face t no , ourn o , s (N.H.). and Derick [9,10] on silicon deserves special We would make some adjustments, get more attention inasmuch as they anticipated planar, oxide- silicon wafers ready, and try again. protected device processing. Silicon is the key ingredien oxids MOSFEr it fo d ey an tpave wa Te dth In the early Spring of 1955, Frosch commented integrated electronics [22]. -

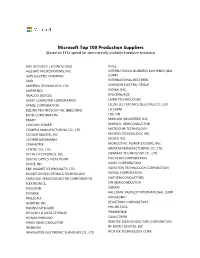

Microsoft Top 100 Production Suppliers (Based on FY14 Spend for Commercially Available Hardware Products)

Microsoft Top 100 Production Suppliers (Based on FY14 spend for commercially available hardware products) AAC ACOUSTIC TECHNOLOGIES INTEL ALLEGRO MICROSYSTEMS, INC. INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES (IBM ALPS ELECTRIC COMPANY CORP.) AMD INTERNATIONAL RECTIFIER AMPEREX TECHNOLOGY, LTD. JOHNSON ELECTRIC GROUP AMPHENOL KIONIX, INC. ANALOG DEVICES KYOCERA/AVX ASKEY COMPUTER CORPORATION LAIRD TECHNOLOGIES ATMEL CORPORATION LELON ELECTRONICS (SUZHOU) CO., LTD BIZLINK TECHNOLOGY INC (BIZCONN) LG CHEM BOYD CORPORATION LITE-ON BRADY MARLOW INDUSTRIES, INC. CHICONY POWER MARVELL SEMICONDUCTOR COMPEQ MANUFACTURING CO., LTD. MICROCHIP TECHNOLOGY COOLER MASTER, INC. MICRON TECHNOLOGY, INC. COOPER BUSSMANN MOLEX, INC. CYMMETRIK MONOLITHIC POWER SYSTEMS, INC. CYNTEC CO., LTD. MURATA MANUFACTURING CO., LTD. DELTA ELECTRONICS, INC. NEWMAX TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. DIGITAL OPTICS VISTA POINT NICHICON CORPORATION DIODE, INC. NIDEC CORPORATION E&E MAGNETICS PRODUCTS, LTD. NUVOTON TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION ELLINGTON ELECTRONICS TECHNOLOGY NVIDIA CORPORATION FAIRCHILD SEMICONDUCTOR CORPORATION NXP SEMICONDUCTORS FLEXTRONICS ON SEMICONDUCTOR FOXCONN OSRAM FOXLINK PALCONN, PALPILOT INTERNATIONAL CORP. FREESCALE PANASONIC GOERTEK, INC. PEGATRON CORPORATION HANNSTAR BOARD PHILIPS PLDS HITACHI-LG DATA STORAGE PRIMESENSE HONDA PRINTING QUALCOMM HYNIX SEMICONDUCTOR REALTEK SEMICONDUCTOR CORPORATION INFINEON RF MICRO DEVICES, INC. INNOVATOR ELECTRONIC SHENZHEN CO., LTD RICHTEK TECHNOLOGY CORP. ROHM CORPORATION SAMSUNG DISPLAY SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS SAMSUNG SDI SAMSUNG SEMICONDUCTOR SEAGATE SHEN ZHEN JIA AI MOTOR CO., LTD. SHENZHEN HORN AUDIO CO., LTD. SHINKO ELECTRIC INDUSTRIES CO., LTD. STARLITE PRINTER, LTD. STMICROELECTRONICS SUNG WEI SUNUNION ENVIRONMENTAL PACKAGING CO., LTD TDK TE CONNECTIVITY TEXAS INSTRUMENTS TOSHIBA TPK TOUCH SOLUTIONS, INC. UNIMICRON TECHNOLOGY CORP. UNIPLAS (SHANGHAI) CO., LTD. UNISTEEL UNIVERSAL ELECTRONICS INCORPORATED VOLEX WACOM CO., LTD. WELL SHIN TECHNOLOGY WINBOND WOLFSON MICROELECTRONICS, LTD. X-CON ELECTRONICS, LTD. YUE WAH CIRCUITS CO., LTD.