History Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa

Safrica Page 1 of 42 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map May 1995 Vol. 7, No.3 SOUTH AFRICA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Continuing Violence in KwaZulu-Natal INTRODUCTION For the last decade South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal region has been troubled by political violence. This conflict escalated during the four years of negotiations for a transition to democratic rule, and reached the status of a virtual civil war in the last months before the national elections of April 1994, significantly disrupting the election process. Although the first year of democratic government in South Africa has led to a decrease in the monthly death toll, the figures remain high enough to threaten the process of national reconstruction. In particular, violence may prevent the establishment of democratic local government structures in KwaZulu-Natal following further elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1995. The basis of this violence remains the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC), now the leading party in the Government of National Unity, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the majority party within the new region of KwaZulu-Natal that replaced the former white province of Natal and the black homeland of KwaZulu. Although the IFP abandoned a boycott of the negotiations process and election campaign in order to participate in the April 1994 poll, following last minute concessions to its position, neither this decision nor the election itself finally resolved the points at issue. While the ANC has argued during the year since the election that the final constitutional arrangements for South Africa should include a relatively centralized government and the introduction of elected government structures at all levels, the IFP has maintained instead that South Africa's regions should form a federal system, and that the colonial tribal government structures should remain in place in the former homelands. -

REFERENCES to COLONIALISM, COLONIAL, and IMPERIALISM South Africa Truth Commission

REFERENCES TO COLONIALISM, COLONIAL, AND IMPERIALISM South Africa Truth Commission Abstract A list of references to colonialism, colonial, and imperialism in the South Africa Truth Commission. Chelsea Barranger Links to Data Visualization This section contains links to all data visualization for the South Africa report. Comparison Charts • References to Colonialism, Colonial, and Imperialism chart • References to Colonialism, Colonial, and Imperialism excel list Word Trees • Colonial • Colonialism • Imperialism References to Colonialism, Colonial, and Imperialism This section contains all references to colonialism, colonial, and imperialism from the South Africa report. <Files\\Truth Commission Reports\\Africa\\SouthAfrica.TRC_.Report-FULL> - § 64 references coded [0.13% Coverage] Reference 1 - 0.01% Coverage 1834 (when slavery was abolished). b The many wars of dispossession and colonial conquest dating from the first war against the Khoisan in 1659, through several so-called frontier conflicts as white settlers penetrated northwards, to the Bambatha uprising of 1906, the last attempt at armed defence by an indigenous grouping. c The systematic hunting and Reference 2 - 0.01% Coverage violation of shocking proportions.2 f The genocidal war in the early years of this century directed by the German colonial administration in South West Africa at the Herero people, which took them to the brink of extinction. 8 It is also important Reference 3 - 0.01% Coverage trees are stripped and leafless. 16 But if this was an act of wholesale dispossession and discrimination, so too was the 1909 South Africa Act which was passed, not by a South African legislature, but by the British Parliament. In terms of the South Africa Act, Britain’s four South African colonies were merged into one nation and granted juridical independence under a constitutional arrangement that transferred power in perpetuity to a minority of white voters. -

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

Race Relations

file:///G|/ProjWip/Products/Omalley/Tim/04%20Transition/T_SAIRR%201990-1994/SAIRR%20Survey%201992-93.HTM RACE RELATIONS SURVEY 1992/93 CAROLE COOPER ROBIN HAMILTON HARRY MASHABELA SHAUN MACKAY ELIZABETH SIDIROPOLOUS CLAIRE GORDON-BROWN STUART MURPHY COLETANE MARHKAM Research staff South African Institute of Race relations SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS JOHANNESBURG 1993 Published by the South African Institute of Race Relations Auden House, 68 De Korte Street file:///G|/ProjWip/Products/Omalley/Tim/04%20Tra...T_SAIRR%201990-1994/SAIRR%20Survey%201992-93.HTM (1 of 914)25/11/2004 15:17:41 PM file:///G|/ProjWip/Products/Omalley/Tim/04%20Transition/T_SAIRR%201990-1994/SAIRR%20Survey%201992-93.HTM Braamfontein, Johannesburg. 2001 South Africa Copyright South African Institute of Race Relations 1993 ISSN 0258-7246 PD4/93 ISBN 0-86982-427-9 Members of the media are free to reprint or report information either in whole or in part, contained in this publication on the strict understanding that the South African Institute of Race Relations is acknowledged. Otherwise, no part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writers of this Survey wish to thank all those who assisted in producing this volume. We are indebted to all those who provided information, among them various organisations, trade unions, companies, government officials, officials of political parties, members of Parliament, academics and other researchers. We wish to thank the Institute’s production co-ordinator, Mrs Carol McCutcheon, for her work in style editing, liaising with the printers and production. -

Background of the Study Area

Chapter 4 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY AREA 4.1 INTRODUCTION In order to understand the factors and circumstances that determine the decision to adopt a new technology, it is important to get a general and integrated overview of the area in which the dependent and the explanatory variables are tested. Both Old and New Qwaqwa are mainly livestock producing areas. To ensure a sustainable livestock production system, the use of veterinary surgeon services and a correct use of medication technologies are essential to the small ruminant farmer (Naude, 1998). The non-adoption of medication technologies usually results in poor reproduction levels and high mortality rates (Schwalbach, 1998). It is therefore important to take a look at the natural resources available to the small ruminant farmers and to evaluate the effect of the quality of these resources on herd health. The intention with this chapter is to give a short historical as well as a geographical background on Qwaqwa. This will be followed by a brief discussion of the land tenure systems, as well as an overview of the agricultural potential, infrastructure and level of institutions in Qwaqwa. In the forth section the diffusion programmes used in the past with regard to the transfer of small ruminant veterinary and medication technologies will be discussed. Background of the study area 70 4.2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF QWAQWA According to the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA, 1985) Old Qwaqwa was previously known as Witsieshoek and Basuto-Barborwa and was occupied by two tribes, namely the Bakwena Tribe (1867) and the Batlokwa Tribe (1873). -

Being Inclusive to Survive in an Ethnic Conflict : the Meaning of ‘Basotho’ for Illegal Squatters in Thaba Nchu, 1970S

Being Inclusive to Survive in an Ethnic Conflict : The Meaning of ‘Basotho’ for Illegal Squatters in Thaba Nchu, 1970s Sayaka Kono University of the Free State, South Africa Tsuda College, Japan Abstract The apartheid regime’s attempt at ‘ethnic division’ practiced through its Bantustan policy caused conflicts in South Africa. A squatter area called Kromdraai became the center of such a conflict between ‘Basotho’ and ‘Batswana’. This paper studies why and how those ex-Kromdraai residents started to claim that they were ‘Basotho’. Firstly, it will discuss the political and economic situation in which the conflict occurred. Secondly, it will argue how politicians of Qwaqwa, a Bantustan for ‘Basotho’, attempted to mobilize people in forming their identity, and why Kromdraai residents got involved in its politics as ‘Basotho’. Thirdly, using oral testimonies, it will reveal the meaning of identifying oneself as ‘Basotho’ for Kromdraai residents. Finally, it will conclude that Kromdraai residents interpreted the word Basotho as being inclusive, not to be ‘ethnically’ exclusive as ‘Batswana’, but at the same time to secure help from Sotho Bantustan, Qwaqwa. Introduction Nation-building has been one of the significant challenges in post-apartheid South Africa. Under the slogan ‘One Nation, Many Cultures’, it places ethnicity as signifying simply cultural difference, and praises the diversity of the ‘Rainbow Nation’. This tendency regarding ethnicity in South Africa today is an attempt to overcome the history of divide and rule. Yet, looking back at how ethnicity was fostered under the apartheid system, it might also mean dismissing the history of the people who had struggled subjectively to solve the problems under the layered structure of the oppression. -

Adoption of Veterinary Surgeon Services by Sheep and Goat Farmers in Qwaqwa

Agrekon, Vol 37, No 4 (December 1999) Nell, Van Schalkwyk, Sanders, Schwalbach & Beser ADOPTION OF VETERINARY SURGEON SERVICES BY SHEEP AND GOAT FARMERS IN QWAQWA W.T.Nell1, H.D. van Schalkwyk2, J.H. Sanders3, L. Schwalbach4 and C.J. Bester5 A number of technology transfer (diffusion) programmes involving amongst others veterinary surgeon services subsidised by the government, were launched in the former homelands of South Africa between 1980 and 1993. Many of these programmes were discontinued after the general election of 1994. In order to evaluate the adoption of technology in Qwaqwa, a former Sotho speaking homeland, two Logit models were fit using the conventional definition of an adopter and an adapted definition, which included potential adopters with the adopters. Where the conventional definition of adoption was estimated, livestock income per LSU, ram technology, roads and suppliers of livestock inputs are significant variables contributing to adoption. The results of the adapted model reveal that farming efficiency (weaning percentage), type of farmer (sheep as percentage of the total small ruminant herd) and ram technology, prove to be significant variables predicting adoption. It was also found that the characteristics of potential adopters gravitate more to adopters than to non-adopters. These results indicated that the adapted definition presented a more accurate prediction than the conventional definition. The results of this study indicate the policy necessary to further accelerate the diffusion of veterinary surgeon services by means of the development of a better infrastructure, the reintroduction of subsidised veterinary surgeon services at the sheering sheds as well as a better flow of information to farmers in Qwaqwa. -

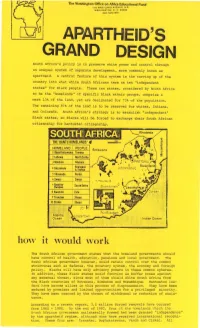

Apartheid's Grand Design

The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund 110 MARYLAND AVENUE. N .E. WASHINGTON. 0. C. 20002 (202) 546-7961 APARTHEID'S GRAND DESIGN South Africa's policy is to preserve white power and control through an unequal system of separate development, more commonly known as apartheid. A central feature of this system is the carving up of the country into what white South Africans term as ten "independent states" for Black people. These ten states, considered by South Africa to be the "homelands" of specific Black ethnic groups, comprise a mere 13% of the land, yet are designated for 73% of the population. The remaining 87% of the land is to be reserved for whites, Indians, and Coloreds. South Africa's strategy is to establish "independent" Black states, so Blacks will be forced to exchange their South African citizenship for bantustan citizenship. THE 'BANTU HOMELANDS' 4 HOMELAND I PEOPLE I Boputhatswanai Tswana 2 lebowa I North Sotho -~ Hdebete Ndebe!e 0 Shangaan Joh<tnnesourg ~ Gazankulu & Tsonga 5 Vhavenda Venda --~------l _ ______6 Swazi 1 1 ___Swazi_ _ _ '7 Basotho . Qwaqwa South Sotho 8 Kwazulu 9 Transkei 10 Ciskei It• vvould w-ork The South African government states that the homeland governments should have control of health, education, pensions and local government. The South African government however, would retain control over t h e common structures such as defense, the monetary s y stem, the economy and foreign policy . Blacks wi ll have only advisory powers in these common spheres. In addition, these Black states would function as buffer zones against any external threat, since most of them shield white South Africa from the Black countries of Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. -

Committed to Unity

Committed to Unity: South Africa’s Adherence to Its 1994 Political Settlement Paul Graham IPS Paper 6 Abstract This paper reviews the commitment of the remaining power contenders and other political actors to the settlement which was reached between 1993 and 1996. Based on interviews with three key actors now in opposing political parties represented in the National Assembly, the paper makes the case for a continued commitment to, and consensus on, the ideals and principles of the 1996 Constitution. It provides evidence of schisms in the dominant power contender (the African National Congress) which have not led to a return in political violence post-settlement. The paper makes the point that, while some of this was the result of President Nelson Mandela’s presence, more must be ascribed to the constitutional arrangements and commitments of the primary political actors and the citizens of South Africa. © Berghof Foundation Operations GmbH – CINEP/PPP 2014. All rights reserved. About the Publication This paper is one of four case study reports on South Africa produced in the course of the collaborative research project ‘Avoiding Conflict Relapse through Inclusive Political Settlements and State-building after Intra-State War’, running from February 2013 to February 2015. This project aims to examine the conditions for inclusive political settlements following protracted armed conflicts, with a specific focus on former armed power contenders turned state actors. It also aims to inform national and international practitioners and policy-makers on effective practices for enhancing participation, representation, and responsiveness in post-war state-building and governance. It is carried out in cooperation with the partner institutions CINEP/PPP (Colombia, Project Coordinators), Berghof Foundation (Germany, Project Research Coordinators), FLACSO (El Salvador), In Transformation Initiative (South Africa), Sudd Institute (South Sudan), Aceh Policy Institute (Aceh/Indonesia), and Friends for Peace (Nepal). -

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa. INSTITUTION South African Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 982 UD 014 924 AUTHOR Horrell, Muriel, Comp.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa. INSTITUTION South African Inst. of Race Relations, Johannesburg. PUB DATE Jan 75 NOTE 449p.; All of the footnotes to the subject matter of the document may not be legible on reproduction due to the print size of the original document AVAILABLE FROM South African Institute of Race Relations, P.O. Box 97, Johannesburg, South Africa (Rand 6.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$22.21 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Activism; Educational Development; Educational Policy; Employment Trends; Federa1 Legislation; Government Role; Law Enforcement; *National Surveys; *Politics; *Public Policl,; *Race Eelations; Racial Discrimination; Racial St!gregation; Racism IDENTIFIERS *Union of South Africa ABSTRACT Sections of this annual report deal with the following topics: political and constitutional developments--the white population group, the colored population group, the Indian group; political affairs of Africans; commissionof inquiry into certain organizations and related matters; organizations concerned with race relations; the population of South Africa; measuresfor security and the control of persons; control of media of communication; justice; liberation movements; foreign affairs; services and amenities for black people in urban areas; group areas and housing: colored, Asian, and whitd population groups; urban African administration; the Pass laws; the African hoL_lands; employment; education: comparative statistics, Bantu school