Northern Ireland Case Study 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

A Democratic Design? the Political Style of the Northern Ireland Assembly

A Democratic Design? The political style of the Northern Ireland Assembly Rick Wilford Robin Wilson May 2001 FOREWORD....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................4 Background.........................................................................................................................................7 Representing the People.....................................................................................................................9 Table 1 Parties Elected to the Assembly ........................................................................................10 Public communication......................................................................................................................15 Table 2 Written and Oral Questions 7 February 2000-12 March 2001*........................................17 Assembly committees .......................................................................................................................20 Table 3 Statutory Committee Meetings..........................................................................................21 Table 4 Standing Committee Meetings ..........................................................................................22 Access to information.......................................................................................................................26 Table 5 Assembly Staffing -

Record Sdlp Annual Conference Ps

l!.I 'tvhf 'I~ , , ,:. (" ® PO L. ~1 i 1( i ( \. li'1. ,:;0 Tk-1\>. , \ cc : PS/Secretary of State (B and L) PAB/1861/DE PS/r1inisters (B) PS/PUS (B an9-L) PS/l'lr ,Bel 1 t./' l"lr Blelloch Mr Marshall (L) l'1r Wyatt I'lr Angel (L) Mr Blatherwick Mr Chesterton (L) Miss MacGlashan Mr .Harringt on (L) l'1r I Orr (Dublin) NOTE FOR Th~ RECORD SDLP ANNUAL CONFERENCE 1. The SDLP held their eleventh Annual Conference in Newcastle on 13-15 November; I attended as an observer. Although the proceedings ,,,,ere overshadowed by the shock of Robert, Bradford t s murder (""hich John. Hume, summing up .the feelings of delegates, described as !tan outright attack on the democratic process ••• &nsfl an overt attempt to provoke this community into civil conflict"), the underlying mood of the Conference was optimisti,c. There were clearly some solid grounds for this confidence: under "very unpromising circumstances the party held its ground in the Nay local elections and maintained its cohesiveness despite the severe pressures of the hunger strik~. Hembership figures were 16% up on the 1980 total (itself a record), and with one or tvlO exceptions delegates showed little inclination to pursue divisive post-mortems on the Fermanagh and South Tyrone by-elections, although some scars remain from thi s episode e (A resolution condemning the failure to field a candidate vIas rejected in private session.) Nonetheless it was evident that the part y has paid a price for survival: preoccupied with copper-fastening its support in the Catholic, community in the face of the extreme republican challenge, the SDLP now shows less sign th&~ ever of understanding the reality of the unionist uosition or in North~rn Irel~~d~ ~ the tru.e scope of the, politically POSSl.Dle; Apart lrom some cautionary words from John Hume, the party leadership did little to lessen many delegates'unrealistic expectations about the imminence of major change in the North's constitutional position iSE,3uing from the Anglo-Irish process. -

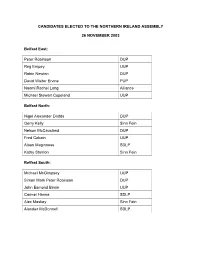

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

What Went Right in Northern Ireland?: an Analysis of Mediation Effectiveness and the Role of the Mediator in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998

What Went Right in Northern Ireland?: An Analysis of Mediation Effectiveness and the Role of the Mediator in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 by Michelle Danielle Everson Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Undergraduate Faculty of the University Honors College and the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy in International and Area Studies University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE This thesis was presented by Michelle D. Everson It was defended on May 29, 2012 and approved by Tony Novosel, Lecturer, Department of History Frank Kerber, Adjunct Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Daniel Lieberfeld, Associate Professor, Graduate Center for Social and Public Policy, Duquesne University Thesis Director: Burcu Savun, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science ii Copyright © by Michelle D. Everson 2012 iii WHAT WENT RIGHT IN NORTHERN IRELAND?: AN ANALYSIS OF MEDIATION EFFECTIVENESS AND THE ROLE OF THE MEDIATOR IN THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT OF 1998 Michelle D. Everson, B.Phil. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 George Mitchell, largely considered the key architect of the Northern Ireland peace process, has been lauded for his ability to find areas of compromise in a conflict that many deemed intractable and few expected to find lasting resolution until the Good Friday Agreement was signed in Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 1998. His success, where -

THE WAY Lt IS Ulster Faces a Crisis Never Before Encountered in Her History

THE WAY lT IS Ulster faces a crisis never before encountered in her history. The British and Dublin Governments have agreed a joint plan to force a united Ireland upon the unionists of Ulster. Their strategy is set out in their joint position paper known as the Framework Document. In its Manifesto “New Labour” have endorsed this betrayal paper. That Document has only one end - the annexation of Northern Ireland by Dublin. HMG and the Dublin Government have made it clear at the Talks that they will not depart from their agreed programme. This Agenda is developed from the Anglo-Irish Agreement, and in particular, the Downing Street Declaration. That Declaration, altered the basis of the principle of consent on the future of Ulster. Before the Joint Declaration Ulster’s future depended on the consent of the people of Northern Ireland alone but the Declaration sets out a new basis for effecting constitutional change in Northern Ireland - the consent of all the people of Ireland. David Trimble, who approves of the Declaration, claimed that - The Orange was safe beneath the Green, while Ken Maginnis affirmed:- Unionists would accept a settlement based on the Downing Street Declaration. At the Talks the Official Unionists have helped to forward the joint agenda of the two Governments - (1) by supporting the forcing of Clinton’s peace envoy, Senator Mitchell, into the Chair. Unbelievably this cave-in came after the Official Unionist Deputy Leader announced that having Senator Mitchell chair the Stormont Talks would be - like having an American Serb chair talks on Bosnia. He could not be considered impartial. -

Civil Rights for All Citizens’ Today

Heritage, History & Memory Project (Workshop 6) The influence, relevance and lessons of the ‘Long 60s’, and the issues of ‘Civil Rights for all Citizens’ today A panel presentation followed by a general discussion compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 125 PAMPHLETS 1 Published February 2020 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2020 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the support they have received from the Heritage Lottery Fund for their Heritage, History & Memory Project and the associated publications Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and Trade Union backgrounds, united in their realisation of the need to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means to realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. In 2018 the Association initiated its ‘Heritage, History & Memory Project’. For the inaugural launch of this project it was decided to focus on the period of the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement, and the early stages of ‘Troubles’. To accomplish this, it was agreed to host a series of six workshops, looking at different aspects of that period, with each workshop developing on from the previous one. This pamphlet details the sixth of those workshops. It took the form of a panel presentation, which was then followed by a general discussion involving people from diverse political backgrounds, who were encouraged to share not only their thoughts on the panel presentation, but their own experiences and memories of the period under discussion. -

Critical Engagement: Irish Republicanism, Memory Politics

Critical Engagement Critical Engagement Irish republicanism, memory politics and policing Kevin Hearty LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Kevin Hearty The right of Kevin Hearty to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78694-047-6 epdf ISBN 978-1-78694-828-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Figures and Tables x List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Understanding a Fraught Historical Relationship 25 2 Irish Republican Memory as Counter-Memory 55 3 Ideology and Policing 87 4 The Patriot Dead 121 5 Transition, ‘Never Again’ and ‘Moving On’ 149 6 The PSNI and ‘Community Policing’ 183 7 The PSNI and ‘Political Policing’ 217 Conclusion 249 References 263 Index 303 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This book has evolved from my PhD thesis that was undertaken at the Transitional Justice Institute, University of Ulster (TJI). When I moved to the University of Warwick in early 2015 as a post-doc, my plans to develop the book came with me too. It represents the culmination of approximately five years of research, reading and (re)writing, during which I often found the mere thought of re-reading some of my work again nauseating; yet, with the encour- agement of many others, I persevered. -

The Peace Process in Northern Ireland

MODULE 3. PATHWAYS TO PEACE 3: THE PEACE PROCESS IN NORTHERN IRELAND LESSON LESSON DESCRIPTION 3. The lesson will detail the difficult path to the Good Friday Agreement through the ceasefires and various political talks that took place. The lesson highlights important talks and ceasefires starting from the Downing Street Declaration up until the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. LESSON INTENTIONS LESSON OUTCOMES 1. Summarise the various attempts • Be able to exhibit an to bring peace to Northern Ireland understanding of the attempts through peace talks made at this time to bring about 2. Consider how paramilitary violence a peace agreement in Northern threatened to halt peace talks Ireland. 3. Demonstrate objectives 1 &2 • Students will be able to recognise through digital media why ceasefires played a key role in the peace process. • Employ ICT skills to express an understanding of the topic. HANDOUTS DIGITAL SOFTWARE HARDWARE AND GUIDES • Lesson 3 Key • Suggested • Audio • Whiteboard Information Additional Editing • PCs / Laptops • M3L3Research Resources Software e.g. • Headphones / Task Audacity Microphones • M3L3Tasksheet • Video • Audio Editing Editing Storyboard Software e.g. Movie Maker • Video Editing Storyboard www.nervecentre.org/teachingdividedhistories MODULE 3: LESSON 3: LESSON PLAN 35 MODULE 3. PATHWAYS TO PEACE 3: THE PEACE PROCESS IN NORTHERN IRELAND ACTIVITY LEARNING OUTCOMES Starter – Students will watch The video will give the students an Suggested Additional Resources 3 opportunity to see the outcome of which describes the beginning of the the political talks that took place in new Northern Ireland government Northern Ireland. The video serves as after the Good Friday Agreement. an introduction to the topic. -

The Road to Sunningdale and the Ulster Workers' Strike of May 1974

Heritage, History & Memory Project (Workshop 4) The Road to Sunningdale and the Ulster Workers’ Strike of May 1974 A presentation by Dr. Aaron Edwards followed by a general discussion compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 116 PAMPHLETS 1 Published July 2019 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2019 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of the Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the support they have received from the Heritage Lottery Fund for their Heritage, History & Memory Project and the associated publications Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of the Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and Trade Union backgrounds, united in their realisation of the necessity to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means of realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. In 2018 the Association initiated its Heritage, History & Memory Project. For the inaugural launch of this project it was decided to focus on the period of the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement, and the early stages of the ‘Troubles’. To accomplish this, it was decided to host a series of six workshops, looking at different aspects of that period. The format for each workshop would comprise a presentation by a respected commentator/historian, which would then be followed by a general discussion involving people from diverse political backgrounds, who would be encouraged to share not only their thoughts on the presentation, but their own experiences and memories of the period under discussion. -

Party Politics in Ireland In

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Huddersfield Repository REDEFINING LOYALISM —A POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE David Ervine, MLA —AN ACADEMIC PERSPECTIVE James W McAuley IBIS working paper no. 4 REDEFINING LOYALISM —A POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE David Ervine, MLA —AN ACADEMIC PERSPECTIVE James W McAuley No. 4 in the lecture series “Redefining the union and the nation: new perspectives on political progress in Ireland” organised in association with the Conference of University Rectors in Ireland Working Papers in British-Irish Studies No. 4, 2001 Institute for British-Irish Studies University College Dublin IBIS working papers No. 4, 2001 © the authors, 2001 ISSN 1649-0304 ABSTRACTS REDEFINING LOYALISM— A POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE Although loyalism in its modern sense has been around since the 1920s, it ac- quired its present shape only at the beginning of the 1970s. Then it was reborn in paramilitary form, and was used by other, more privileged, unionists to serve their own interests. Yet the sectarianism within which loyalism developed disguised the fact that less privileged members of the two communities had much in common. Separation bred hatred, and led to an unfounded sense of advantage on the part of many Protestants who in reality enjoyed few material benefits. The pursuit of ac- commodation between the two communities can best be advanced by attempts to understand each other and to identify important shared interests, and the peace process can best be consolidated by steady, orchestrated movement on the two sides, and by ignoring the protests of those who reject compromise. REDEFINING LOYALISM— AN ACADEMIC PERSPECTIVE In recent years a division has emerged within unionism between two sharply con- trasting perspectives. -

"NORTHERN IRELAND CONFLICT" By: Tariq Al-Ansari

INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESOLUTION Paper on "NORTHERN IRELAND CONFLICT" By: Tariq Al-Ansari I. Introduction 1. Throughout history, the island of Ireland has been regarded as a single national unit. Prior to the Norman invasions from England In 1169, the Irish people were distinct from other nations, cultivating their own system of law, culture, language, and political and social structures. Until 1921, the island of Ireland was governed as a single political unit as a colony of Britain. A combined political/military campaign by Irish nationalists between the years 1916 to 1921 forced the British government to consider its position. Partition was imposed on the Irish people by an Act of Parliament, the Government of Ireland Act (1920), passed in the British legislature. The consent of the Irish people was never sought and was never freely given. 2. With the objective of “protecting English interests with an economy of English lives” (Lord Birkenhead), the partition of Ireland was conceived. Proffered as a solution under the threat of ''immediate and terrible war'' (Lloyd George, the then British Prime Minister). The Act made provision for the creation of two states in Ireland: the ''Irish Free State'' (later to become known as the Republic of Ireland), containing 26 of Ireland's 32 counties; and ''Northern Ireland'' containing the remaining six counties. 3. Northern Ireland (the Six Counties) represented the greatest land area in which Irish unionists could maintain a majority. The partition line first proposed had encompassed the whole province of Ulster (nine counties). Unionists rejected this because they could not maintain a majority in such an enlarged area.