2.01.73 Actigraphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

533 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.01.73 NCD/LCD: N/A

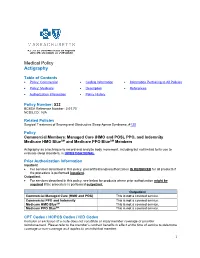

Medical Policy Actigraphy Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History Policy Number: 533 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.01.73 NCD/LCD: N/A Related Policies Surgical Treatment of Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, #130 Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Medicare HMO BlueSM and Medicare PPO BlueSM Members Actigraphy as a technique to record and analyze body movement, including but not limited to its use to evaluate sleep disorders, is INVESTIGATIONAL. Prior Authorization Information Inpatient • For services described in this policy, precertification/preauthorization IS REQUIRED for all products if the procedure is performed inpatient. Outpatient • For services described in this policy, see below for products where prior authorization might be required if the procedure is performed outpatient. Outpatient Commercial Managed Care (HMO and POS) This is not a covered service. Commercial PPO and Indemnity This is not a covered service. Medicare HMO BlueSM This is not a covered service. Medicare PPO BlueSM This is not a covered service. CPT Codes / HCPCS Codes / ICD Codes Inclusion or exclusion of a code does not constitute or imply member coverage or provider reimbursement. Please refer to the member’s contract benefits in effect at the time of service to determine coverage or non-coverage as it applies to an individual member. 1 Providers should report all services using the most up-to-date industry-standard procedure, revenue, and diagnosis codes, including modifiers where applicable. CPT Codes CPT codes: Code Description 95803 Actigraphy testing, recording, analysis, interpretation and report (minimum of 72 hours to 14 consecutive days of recording) ICD Diagnosis Codes Investigational for all diagnoses. -

ACTIGRAPHY Wactisleep-BT Monitor Micro Motionlogger Watch Motionlogger Watch Motionwatch 8 Actiwatch Spectrum Somnowatch

Company ActiGraph Ambulatory Monitoring Inc CamNtech Philips Respironics SOMNOmedics America Inc Product Name ACTIGRAPHY wActiSleep-BT Monitor Micro Motionlogger Watch Motionlogger Watch MotionWatch 8 Actiwatch Spectrum SOMNOwatch www.ambulatory-monitoring. www.ambulatory-monitoring. www.somnomedics- Website www.actigraphcorp.com www.camntech.com www.philips.com/actigraphy com com diagnostics.com 1-year standard warranty; Cost/Warranty $299/1 year 1 year 1 year $750/2 years 2 years extended warranty available 3-axis solid state Miniaturized poly-silicone-surface Accelerometer accelerometer with digital Solid state triaxial Solid state triaxial MEMS – 3 axis Solid-state “piezoelectric” micromachined Technology filtering sensor (MEMS) 3.81 cm x 2.54 cm x 1.016 Product Dimensions 4.6 cm x 3.3 cm x 1.9 cm 3.6 cm x 3.6 cm x 1.2 cm 5.5 cm x 4.5 cm x 1.8 cm H 4.8 cm x 3.7 cm x 1.4 cm 4.5 cm x 4.5 cm x 1.6 cm cm Weight, Including 22 grams 30 grams 65 grams 16.8 grams 30 grams 30 grams Batteries and Wrist Band Rechargeable lithium Li-Ion-Accu, inbuilt, Batteries 1 DL2430 disposable coin cell 1 DL2450 disposable coin cell Common watch R2032 Lithium coin cell CR 2430 polymer rechargeable 1-year battery life (with continuous Battery Life 31 days 30+ days 30+ days 1 year 26+ days use at 1-minute epoch) Type of Memory Storage 2 GB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 4 MB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 8 MB internal storage card Recording Time at 1- 36 days—Activity plus 120 days 30+ days 30+ days 182 days 45 days Minute Sample Interval 4 channels -

And Irregular Sleep-Wake-Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD): How Many Days Are Needed for Reliable Measures?

Activity Monitoring in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Irregular Sleep-Wake-Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD): How Many Days are needed for reliable measures? Manuel Kemethofer1, Georg Gruber1, Georg Dorffner1,2, Silvia Parapatics1, Erna Loretz1, Marco Hirner1, Mohammad Bsharat3, Gleb Filppov3, Naoki Kubota4, Margaret Moline3 Affiliations: 1: The Siesta Group; 2: Medical University of Vienna, Section for Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support, Vienna, Austria; 3: Eisai, Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA; 4: Eisai Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Methodological Question How many days of actigraphy data are needed for reliable measures of sleep-wake patterns in patients with AD and ISWRD? Introduction When sleep is not consolidated at night but rather distributed in irregular sleep bouts across the 24- hour period, this condition is referred to as Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm Disorder (ISWRD) and often appears early in the course of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). To obtain reliable information about a patient’s sleep-wake rhythm, multiple 24-hour periods must be investigated. With actigraphy this is possible. For children and adolescents, it is recommended1 to record at least one week of actigraphy data to provide an adequate information. However, it is still unclear how many days of actigraphy data are needed for determining reliable measures of sleep-wake patterns in patients with AD and ISWRD. Methods A retrospective analysis of data from 121 subjects (aged 60 – 90 years) with a diagnosis of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s Disease, a Mini–Mental State Examination score between 10-26 and complaints of difficulties with both staying asleep during night and staying awake during day occurring at least 3 times per week for at least 3 months was performed. -

Actigraphy As a Diagnostic Aid for REM Sleep Behavior Disorder In

Louter et al. BMC Neurology 2014, 14:76 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/14/76 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Actigraphy as a diagnostic aid for REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease Maartje Louter1,2, Johan BAM Arends3,4, Bastiaan R Bloem1 and Sebastiaan Overeem1,2* Abstract Background: Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a common parasomnia in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients. The current International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-II) requires a clinical interview combined with video polysomnography (video-PSG) to diagnose. The latter is time consuming and expensive and not always feasible in clinical practice. Here we studied the use of actigraphy as a diagnostic tool for RBD in PD patients. Methods: We studied 45 consecutive PD patients (66.7% men) with and without complaints of RBD. All patients underwent one night of video-PSG and eight consecutive nights of actigraphy. Based on previous studies, the main outcome measure was the total number of bouts classified as “wake”, compared between patients with (PD + RBD) and without RBD (PD- RBD). Results: 23 (51.1%) patients had RBD according to the ICSD-II criteria. The total number of wake bouts was significantly higher in RBD patients (PD + RBD 73.2 ± 40.2 vs. PD-RBD 48.4 ± 23.3, p = .016). A cut off of 95 wake bouts per night resulted in a specificity of 95.5%, a sensitivity of 20.1% and a positive predictive value of 85.7%. Seven patients were suspected of RBD based on the interview alone, but not confirmed on PSG; six of whom scored below 95 wake bouts per night on actigraphy. -

Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Revisited – a Case Study

CASE REPORT published: 29 February 2016 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00017 Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Revisited – a Case study Corrado Garbazza1,2† , Vivien Bromundt3† , Anne Eckert2,4 , Daniel P. Brunner5 , Fides Meier2,4 , Sandra Hackethal6 and Christian Cajochen1,2* 1 Centre for Chronobiology, Psychiatric Hospital of the University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 2 Transfaculty Research Platform Molecular and Cognitive Neurosciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 3 Sleep-Wake-Epilepsy-Centre, Department of Neurology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland, 4 Neurobiology Laboratory for Brain Aging and Mental Health, Psychiatric Hospital of the University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 5 Center for Sleep Medicine, Hirslanden Clinic Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 6 Charité – Universitaetsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany The human sleep-wake cycle is governed by two major factors: a homeostatic hourglass process (process S), which rises linearly during the day, and a circadian process C, which determines the timing of sleep in a ~24-h rhythm in accordance to the external Edited by: Ahmed S. BaHammam, light–dark (LD) cycle. While both individual processes are fairly well characterized, the King Saud University, Saudi Arabia exact nature of their interaction remains unclear. The circadian rhythm is generated by Reviewed by: the suprachiasmatic nucleus (“master clock”) of the anterior hypothalamus, through Axel Steiger, cell-autonomous feedback loops of DNA transcription and translation. While the phase Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Germany length (tau) of the cycle is relatively stable and genetically determined, the phase of Timo Partonen, the clock is reset by external stimuli (“zeitgebers”), the most important being the LD National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland cycle. -

The Feasibility of Sleep Assessment by Actigraph in Patients with Tetraplegia

Spinal Cord (2007) 45, 765–770 & 2007 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/sc Original Article The feasibility of sleep assessment by actigraph in patients with tetraplegia E Spivak1, A Oksenberg2 and A Catz*,1,3 1Department of Spinal Rehabilitation, Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital, Raanana, Israel; 2Sleep Disorders Unit at Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital, Raanana, Israel; 3Tel Aviv University, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv, Israel Background: Sleep disturbances are frequent in patients with high spinal cord lesions, and are difficult to diagnose by means of polysomnography (PSG). Design: Retrospective cohort study. Objective: Examine the feasibility of sleep assessment by actigraph in patients with tetraplegia. Setting: A rehabilitation center in Israel. Subjects: Twenty-one patients with tetraplegia and 20 healthy persons. Interventions: Sleep assessment by actigraphs attached tothe head and the wrist. Main outcome measures: The actigraphic movement index (MI), total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE), wake after sleep onset (WASO), sleep latency (SL), and number of awakenings (NOA). Results: In the control group actigraphy showed that during sleep the hand moves more than the head but that the movements were highly correlated. In patients with tetraplegia below C5–C7 the hand also moved more than the head, but in patients with tetraplegia below C4, the head moved more (Po0.05). Nosignificant differences were found between patients with C 5–C7 tetraplegia and healthy controls in the sleep indices obtained by hand movements, or between patients with C4 tetraplegia and healthy controls in the indices obtained by head movements. Control subjects and patients showed similar subjective assessment of sleep quality. -

Trauma Associated Sleep Disorder: a Parasomnia Induced by Trauma

Sleep Medicine Reviews 37 (2018) 94e104 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Sleep Medicine Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/smrv THEORETICAL REVIEW Trauma associated sleep disorder: A parasomnia induced by trauma * Vincent Mysliwiec a, , Matthew S. Brock a, Jennifer L. Creamer b, Brian M. O'Reilly b, Anne Germain c, d, Bernard J. Roth b a San Antonio Military Medical Center, Department of Sleep Medicine, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, JBSA Lackland, TX 78236, USA b Madigan Army Medical Center, Department of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Tacoma, WA, USA c University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Pittsburgh, PA, USA d University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychology, Pittsburgh, PA, USA article info summary Article history: Nightmares and disruptive nocturnal behaviors that develop after traumatic experiences have long been Received 15 May 2016 recognized as having different clinical characteristics that overlap with other established parasomnia Received in revised form diagnoses. The inciting experience is typically in the setting of extreme traumatic stress coupled with 12 January 2017 periods of sleep disruption and/or deprivation. The limited number of laboratory documented cases and Accepted 20 January 2017 symptomatic overlap with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) and posttraumatic stress Available online 30 January 2017 disorder (PTSD) have contributed to difficulties in identifying what is a unique parasomnia. Trauma associated -

Actigraphy Original Effective Date: 9/16/20

Subject: Actigraphy Original Effective Date: 9/16/20 Policy Number: MCP-374 Revision Date(s): Review Date: 11/18/20 MCPC Approval Date: 9/16/20 DISCLAIMER This Molina Clinical Policy (MCP) is intended to facilitate the Utilization Management process. It expresses Molina's determination as to whether certain services or supplies are medically necessary, experimental, investigational, or cosmetic for purposes of determining appropriateness of payment. The conclusion that a particular service or supply is medically necessary does not constitute a representation or warranty that this service or supply is covered (i.e., will be paid for by Molina) for a particular member. The member's benefit plan determines coverage. Each benefit plan defines which services are covered, which are excluded, and which are subject to dollar caps or other limits. Members and their providers will need to consult the member's benefit plan to determine if there are any exclusion(s) or other benefit limitations applicable to this service or supply. If there is a discrepancy between this policy and a member's plan of benefits, the benefits plan will govern. In addition, coverage may be mandated by applicable legal requirements of a State, the Federal government or CMS for Medicare and Medicaid members. CMS's Coverage Database can be found on the CMS website. The coverage directive(s) and criteria from an existing National Coverage Determination (NCD) or Local Coverage Determination (LCD) will supersede the contents of this Molina Clinical Policy (MCP) document and -

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

alt y He hca ar re : im O r p P e f n o A l c a Wells and Overton, Primary Health Care 2014, 4:2 c n e r s u Primary Health Care: Open Access s o DOI: 10.4172/2167-1079.1000158 J ISSN: 2167-1079 Review Article Open Access Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders Mary Ellen Wells1* and Auburne Overton1 1University of North Carolina, USA *Corresponding author: Mary Ellen Wells, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Allied Health Sciences, 301 A South Columbia StreetCB # 7120 Chapel Hill, NC27516, USA, Tel: 919-843-4673; Email: [email protected] Rec date: Mar 26, 2014, Acc date: May 20, 2014; Pub date: May 28, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Wells ME, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Though the theories on the reasons why humans need to sleep vary, there is no disagreement that sleep is essential to our wellbeing and survival. External and internal physiological parameters dictate our own individual body “clocks,” or circadian rhythms. Typically, this clock runs very close to a 24-hour cycle of sleep and wakefulness. However, for some individuals, this clock can be slightly “off.” This article will discuss what creates internal circadian rhythms and the major types of circadian rhythm disorders, with an overview of diagnosis and treatment options. Keywords: Sleep medicine; Circadian rhythms; Sleep physiology; deprived of sleep will die within two to three weeks, a time frame Delayed phase sleep disorder; Advanced phase sleep disorder; Jet lag; similar to death due to starvation [5].” Non-entrained type; Free-running type; Irregular sleep-wake rhythm; A recent and widely accepted definition of sleep, according to the Shift work type American Academy of Sleep Medicine is: “Sleep is much more than a gentle ‘pause’ from your daily activities. -

A Review of Sleep Diary Accuracy

183 Original Article Assessing the sleeping habits of patients in a sleep disorder centre: a review of sleep diary accuracy Geoffrey Lawrence1, Rexford Muza2 1GKT School of Medical Education, King’s College London, London, UK; 2Sleep Disorders Centre, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: R Muza; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: R Muza; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: G Lawrence; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: G Lawrence; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Rexford Muza. Sleep Disorders Centre, St Thomas’ Hospital, Guy’s Hospital Sleep Disorders Centre 3rd floor, Nuffield House Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, UK. Email: [email protected]. Background: Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is a complaint common to many aspects of medicine. There are primary and secondary causes for EDS, with secondary causes including a large number of common conditions. Primary causes, such as narcolepsy, are much rarer. When assessing for primary hypersomnia, restricted or fragmented sleep must be ruled out. This process involves assessment of sleeping habits using a sleep diary and/or actigraphy. Clinicians are suspicious of the accuracy with which patients use the former. This review aims to evaluate the accuracy of a sleep diary study against the ‘objective gold standard’ actigraphy report. Methods: Data from 35 patients at a Sleep Disorder Centre who underwent both a sleep diary and actigraphy study for suspected primary hypersomnia in 2016 was collected. Mean values of four variables were calculated: ‘time of lights out’, ‘time to fall asleep’, ‘time of waking’ and ‘sleep time’. -

IH Summary: Characteristics & Diagnostic Criteria

Idiopathic Hypersomnia (IH) Characteristics STANDARD CHARACTERISTICS: • Neurological disorder1, 3 • Chronic, usually lifelong after onset1, 2, 3, 4 • A central disorder of hypersomnolence (CDH), in the same category as narcolepsy1, 3 • Hallmark symptom: excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), an uncontrollable need to sleep or daytime sleepiness that persists for at least 3 months even with adequate or prolonged nighttime sleep1, 2, 3, 4 POSSIBLE CHARACTERISTICS: • Debilitating, often significantly affecting social, school, and occupational functioning1, 2, 3, 4 • Onset usually in adolescence or early adulthood (but may be earlier or later)1, 2, 3, 4 • Seems to affect more females than males2, 3 • Fluctuating severity, with some time periods worse than others2, 4 • Daytime naps, which are generally long (over 1 hour) and usually not refreshing [frequent]1, 2, 3, 4 • Long sleep: sleeping 9 hours4 or more3 in 24 hours, which is usually un-refreshing [frequent]1, 2, 3, 4 • Sleep drunkenness (i.e., severe sleep inertia): extreme and prolonged difficulty fully awakening, associated with an uncontrollable desire to go back to sleep [frequent], which can be accompanied by automatic behavior (performing tasks without conscious self-control and with partial or total loss of memory), disorientation, confusion, irritability, and poor coordination1,2,3,4 • Motor hyperactivity ”e.g., “never stopping,” “speaking a lot”), serving as a countermeasure to boost alertness [frequent]2, 3, 4 • Cognitive dysfunction: deficits in memory, attention, and concentration (sometimes referred to informally as “brain fog”)2, 4 • Sleep hallucinations: hallucinations at sleep onset and/or offset occasional[ ]1, 3 • Sleep paralysis: a transitional state between wakefulness and sleep, in which one is aware but cannot move, speak, or react [occasional]1, 3 • Additional potential symptoms: headaches, automatic behaviors, problems with balance, and difficulties with temperature regulationoccasional [ ]2, 3, 4 • Unique anesthesia needs: see hypersomniafoundation.org/anesthesia-and-ih Sources: 1. -

International Classification of Sleep Disorders

[ Contemporary Reviews in Sleep Medicine ] I n t e r n a t i o n a l C l a s s i fi cation of Sleep Disorders-Th ird Edition Highlights and Modifi cations Michael J. Sateia , MD The recently released third edition of the International Classifi cation of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) is a fully revised version of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s manual of sleep disorders nosology, published in cooperation with international sleep societies. It is the key reference work for the diagnosis of sleep disorders. The ICSD-3 is built on the same basic outline as the ICSD-2, identifying seven major categories that include insomnia disorders, sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence, circadian rhythm sleep-wake dis- orders, sleep-related movement disorders, parasomnias, and other sleep disorders. Signifi cant modifi cations have been made to the nosology of insomnia, narcolepsy, and parasomnias. Major features and changes of the manual are reviewed in this article. The rationales for these changes are also discussed. CHEST 2014; 146 ( 5 ): 1387- 1394 ABBREVIATIONS : A A S M 5 American Academy of Sleep Medicine ; CRSWD 5 circadian rhythm sleep- wake disorder ; CSA 5 central sleep apnea ; CSB 5 Cheyne-Stokes breathing ; ICD 5 International Classification of Diseases ; I C S D 5 International Classification of Sleep Disorders ; I H 5 idiopathic hypersomnia ; MSLT 5 multiple sleep latency test ; NREM 5 non-rapid eye movement ; OCST 5 out-of- center sleep testing ; PAP 5 p o s i t i v e a i r w a y p r e s s u r e ; P L M 5 periodic limb movement ; PLMD 5 p e r i o d i c limb movement disorder ; PSG 5 polysomnogram ; RBD 5 rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder ; REM 5 rapid eye movement ; RLS 5 restless legs syndrome ; SOREMP 5 sleep-onset rapid eye movement p e r i o d Th e recent publication of the third edition recommendations were added.