Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Revisited – a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circadian Disruption: What Do We Actually Mean?

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Eur J Neurosci Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2020 May 07. Circadian disruption: What do we actually mean? Céline Vetter Department of Integrative Physiology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA Abstract The circadian system regulates physiology and behavior. Acute challenges to the system, such as those experienced when traveling across time zones, will eventually result in re-synchronization to the local environmental time cues, but this re-synchronization is oftentimes accompanied by adverse short-term consequences. When such challenges are experienced chronically, adaptation may not be achieved, as for example in the case of rotating night shift workers. The transient and chronic disturbance of the circadian system is most frequently referred to as “circadian disruption”, but many other terms have been proposed and used to refer to similar situations. It is now beyond doubt that the circadian system contributes to health and disease, emphasizing the need for clear terminology when describing challenges to the circadian system and their consequences. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the terms used to describe disruption of the circadian system, discuss proposed quantifications of disruption in experimental and observational settings with a focus on human research, and highlight limitations and challenges of currently available tools. For circadian research to advance as a translational science, clear, operationalizable, and scalable quantifications of circadian disruption are key, as they will enable improved assessment and reproducibility of results, ideally ranging from mechanistic settings, including animal research, to large-scale randomized clinical trials. -

Participant Guide

Participant Guide Get Enough Sleep Session Focus Getting enough sleep can help you prevent or delay type 2 diabetes. This session we will talk about: z Why sleep matters z Some challenges of getting enough sleep and ways to cope with them You will also make a new action plan! Tips: ✓ Go to bed and get up at the same time each day. This helps your body get on a schedule. ✓ Follow a bedtime routine that helps you wind down. Participant Guide: Get Enough Sleep 2 Jenny’s Story Jenny is at risk for type 2 diabetes. Her doctor asks her if she gets at least 7 hours of sleep each night. Jenny laughs. “Are you serious?” she asks. “I’m lucky if I get 5 hours.” Jenny usually doesn’t have much trouble falling asleep. But she often has to use the bathroom in the early morning. This gets her thinking about all the things she needs to do the next day. Plus, her husband’s breathing is loud. Both of these things make it hard for Jenny to fall back to sleep. She often lies awake for hours. These days, Jenny drinks less water and avoids caffeine in the evening. She makes a list of things to do the next day. Then she sets it aside. Jenny rarely needs to get up to use the bathroom during the night. If she does, she breathes deeply to help her get back to sleep. She also runs a fan to cover up the sound of her husband’s breathing. Jenny is closer to getting 7 hours of sleep a night. -

Circadian Rhythms Fact Sheet

Circadian Rhythms Circadian rhythms are physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. What are circadian rhythms? Circadian rhythms are physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. These natural processes respond primarily to light and dark and affect most living things, including animals, plants, and microbes. Chronobiology is the study of circadian rhythms. One example of a light-related circadian rhythm is sleeping at night and being awake during the day. The image to the right shows the circadian rhythm cycle of a typical teen. What are biological clocks? Biological clocks are organisms’ natural timing devices, regulating the cycle of circadian rhythms. They’re composed of specific molecules (proteins) Circadian rhythm cycle of a typical teenager. that interact with cells throughout the body. Credit: NIGMS Nearly every tissue and organ contains biological clocks. Researchers have identified similar genes in people, fruit flies, mice, plants, fungi, and several What is the master clock? other organisms that make the clocks’ molecular A master clock in the brain coordinates all the components. biological clocks in a living thing, keeping the clocks in sync. In vertebrate animals, including humans, the master clock is a group of about 20,000 nerve cells (neurons) that form a structure called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN. The SCN is in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus and Light receives direct input from the eyes. Your brain’s “master clock” Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) Hypothalamus (or SCN) receives (Soop-ra-kias-MA-tic NU-klee-us) (Hype-o-THAL-a-mus) light cues from the environment. -

Slow-Wave Sleep, Diabetes, and the Sympathetic Nervous System

COMMENTARY Slow-wave sleep, diabetes, and the sympathetic nervous system Derk-Jan Dijk* Surrey Sleep Research Centre, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey GU2 7XP, United Kingdom leep oscillates between two dif- of SWS that has accumulated. The latter less provides supportive evidence for the ferent states: non-rapid eye conclusion was derived from SWS depri- notion that SWS is restorative also for movement (NREM) sleep and vation experiments in which stimuli, usu- the body and that negative effects asso- rapid-eye movement (REM) ally acoustic stimuli [although early on ciated with disruption of this state may Ssleep. Slow-wave sleep (SWS) is a sub- in the history of SWS deprivation, mild extend to the body. state of NREM sleep, and its identifica- electric shocks were used (5)], are deliv- Many other physiological variables are tion is based primarily on the presence ered in response to the ongoing EEG. affected by the behavioral-state sleep, of slow waves, i.e., low-frequency, high- The drive to enter SWS is strong and is the NREM–REM cycle, and SWS. amplitude oscillations in the EEG. Upon the transition from wakefulness to Quantification of SWS is accomplished sleep, heart rate slows down. During by visual inspection of EEG records or Short habitual sleep sleep, the balance of sympathetic and computerized methods such as spectral parasympathetic tone oscillates in syn- analysis based on the fast Fourier trans- has been associated chrony with the NREM–REM cycle. form (FFT). Slow-wave activity (SWA; Analysis of autonomic control of the also referred to as delta power) is a with increased risk variability of heart rate demonstrates quantitative measure of the contribution that, within each NREM episode, as of both the amplitude and prevalence of for diabetes. -

No Evidence for a Phase Delay in Human Circadian Rhythms After a Single Morning Melatonin Administration

J. Pineal Res. 2002; 32:1±5 Copyright ã Munksgaard, 2002 Journal of Pineal Research ISSN 0742-3098 No evidence for a phase delay in human circadian rhythms after a single morning melatonin administration Wirz-Justice A, Werth E, Renz C, MuÈ ller S, KraÈ uchi K. No evidence for a Anna Wirz-Justice, Esther Werth, phase delay in human circadian rhythms after a single morning melatonin Claudia Renz, Simon MuÈ ller and administration. J. Pineal Res. 2002; 32: 1±5. ã Munksgaard, 2002 Kurt KraÈuchi Abstract: Although there is good consensus that a single administration of Centre for Chronobiology, Psychiatric University Clinic, Basel, Switzerland melatonin in the early evening can phase advance human circadian rhythms, the evidence for phase delay shifts to a single melatonin stimulus given in the early morning is sparse. We therefore carried out a double-blind randomized- order placebo-controlled study under modi®ed constant routine (CR) conditions (58 hr bedrest under 8 lux with sleep 23:00±07:00 hr) in nine healthy young men. A single (pharmacological) dose of melatonin (5 mg p.o.) or a placebo was administered at 07:00 hr on the ®rst morning. Core body temperature (CBT) and heart rate (HR) were continuously recorded, and saliva was collected half-hourly for assay of melatonin. Neither the timing of the mid-range crossing times of temperature (MRCT) and HR rhythms, nor dim light melatonin onset (DLMOn) or oset (DLMO) were phase shifted the day after melatonin administration compared with placebo. Key words: human circadian rhythms, morning The only change was an altered wave form of the CBT rhythm: longer melatonin, phase delay duration of higher-than-average temperature after melatonin administration. -

Sleep Apnea Sleep Apnea

Health and Safety Guidelines 1 Sleep Apnea Sleep Apnea Normally while sleeping, air is moved at a regular rhythm through the throat and in and out the lungs. When someone has sleep apnea, air movement becomes decreased or stops altogether. Sleep apnea can affect long term health. Types of sleep apnea: 1. Obstructive sleep apnea (narrowing or closure of the throat during sleep) which is seen most commonly, and, 2. Central sleep apnea (the brain is causing a change in breathing control and rhythm) Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) About 25% of all adults are at risk for sleep apnea of some degree. Men are more commonly affected than women. Other risk factors include: 1. Middle and older age 2. Being overweight 3. Having a small mouth and throat Down syndrome Because of soft tissue and skeletal alterations that lead to upper airway obstruction, people with Down syndrome have an increased risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Statistics show that obstructive sleep apnea occurs in at least 30 to 75% of people with Down syndrome, including those who are not obese. In over half of person’s with Down syndrome whose parents reported no sleep problems, sleep studies showed abnormal results. Sleep apnea causing lowered oxygen levels often contributes to mental impairment. How does obstructive sleep apnea occur? The throat is surrounded by muscles that are active controlling the airway during talking, swallowing and breathing. During sleep, these muscles are much less active. They can fall back into the throat, causing narrowing. In most people this doesn’t affect breathing. However in some the narrowing can cause snoring. -

Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Australia

Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Australia A REPORT TO THE SLEEP HEALTH FOUNDATION 1,2 1. Appleton Institute, CQUniversity Australia 44 Greenhill Amy C Reynolds Road, Wayville SA 5034 3,4 Sarah L Appleton 2. School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity Australia 4,5 Tiffany K Gill 3. Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health: A Flinders Centre of Robert J Adams 3,4 Research Excellence, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA. 4. The Health Observatory, Adelaide Medical School, The University of Adelaide, SA. 5. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, Australia Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Australia A Report to the Sleep Health Foundation Amy C Reynolds1,2, Sarah L Appleton3,4, Tiffany K Gill4,5 & Robert J Adams3,4 1. Appleton Institute, CQUniversity Australia 44 Greenhill Road, Wayville SA 5034 2. School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity Australia 3. Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health: A Flinders Centre of Research Excellence, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA. 4. The Health Observatory, Adelaide Medical School, The University of Adelaide, SA. 5. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, Australia This work was supported by the Sleep Health Foundation, an Australian not‑for‑profit organisation devoted to improving sleep health, and an unrestricted grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Limited which had no part in conception, planning, execution or write‑up of it. Publication and graphic design by Flux Visual Communication www.designbyflux.com.au July 2019 2 Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Australia EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sleep problems are common and costly to the Australian community. One common sleep condition is insomnia. -

Towards a Passive BCI to Induce Lucid Dream Morgane Hamon, Emma Chabani, Philippe Giraudeau

Towards a Passive BCI to Induce Lucid Dream Morgane Hamon, Emma Chabani, Philippe Giraudeau To cite this version: Morgane Hamon, Emma Chabani, Philippe Giraudeau. Towards a Passive BCI to Induce Lucid Dream. Journée Jeunes Chercheurs en Interfaces Cerveau-Ordinateur et Neurofeedback 2019 (JJC- ICON ’19), Mar 2019, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France. hal-02108903 HAL Id: hal-02108903 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02108903 Submitted on 29 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TOWARDS A PASSIVE BCI TO INDUCE LUCID DREAM JJC-ICON ’19 Morgane Hamon Emma Chabani Philippe Giraudeau Ullo Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle épinière Inria La Rochelle, France Paris, France Bordeaux, France [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] April 29, 2019 ABSTRACT Lucid dreaming (LD) is a phenomenon during which the person is aware that he/she dreaming and is able to control the dream content. Studies have shown that only 20% of people can experience lucid dreams on a regular basis. However, LD frequency can be increased through induction techniques. External stimulation technique relies on the ability to integrate external information into the dream content. -

Sleep & Dreams & Dsm-5

PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 SLEEP & DREAMS & DSM-5: ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC INSOMNIA James Peacey, MD PAL Conference Green River, WY Disclosure Statement No relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider of commercial services discussed in this CME activity. I will reference off-label or investigational use of medications in this presentation. PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Goals and Objectives Learn how to identify and categorize pediatric insomnia. Increase knowledge of common behavioral and pharmacologic sleep treatments. Increase understanding of sleep issues in particular patient populations (Autism, ADHD, depression and anxiety) and appropriate strategies to optimize treatment. PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Sleep Stage Development PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Homeostatic and Circadian Processes D. J. Dijk and D. M. Edgar, Regulation of Sleep and Wakefulness, 1999 PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Homeostatic and Circadian Processes PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Alerting Systems PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Normal Sleep Requirements Babcock, Pediatr Clin N Am 58 (2011) 543–554PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 Percentiles for total sleep duration per 24 hours from infancy to adolescence. Iglowstein I et al. Pediatrics 2003;111:302-307 PAL Conference - Green River, WY - May 2015 ©2003 by American Academy of Pediatrics Insomnia “significant difficulty initiating -

Sleep Disorders and Deprivation Causes and Effects on College Students Reham Karana Biology, Bachelors of Science to the Honors

Sleep Disorders and Deprivation Causes and Effects on College Students Reham Karana Biology, Bachelors of Science To The Honors College Oakland University In partial fulfillment of the requirement to graduate from The Honors College Mentor: Jessica Koppen, Professor of Chemistry Department of Chemistry Oakland University (February 15, 2018) Introduction When told to picture a college student, a picture of a student in a library frantically studying for their next exam will most likely come to mind. Others might picture college students in a social environment among their peers, participating in a sorority, or even at a raucous party. What most will not picture a college student doing is simply sleeping. A growing and unattended problem among college students is their common day-time sleepiness and increased sleep disorders. A student’s sleep is no longer driven by the light and dark cycle but rather but their school schedule, academic load, and socialization. To maximize success in college, an obstacle most students have now endured is a lack of sleep and potential sleep disorders. What most do not know is this could actually do the opposite and hurt academic performance (Allan, 2015). Current research has shown that fifty percent of college students report daytime sleepiness and seventy percent experience insufficient sleep (Hershner, 2014). This can adversely affect one’s academic performance due to sleep having vital biological effects on the human body (Gaultney, 2010). According to The American Academy of Sleep Medicine, students that maintain a sufficient amount of sleep per night performed better on memory and motor tasks than students deprived of sleep (“College Students”, 2015). -

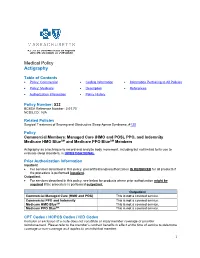

533 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.01.73 NCD/LCD: N/A

Medical Policy Actigraphy Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History Policy Number: 533 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.01.73 NCD/LCD: N/A Related Policies Surgical Treatment of Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, #130 Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Medicare HMO BlueSM and Medicare PPO BlueSM Members Actigraphy as a technique to record and analyze body movement, including but not limited to its use to evaluate sleep disorders, is INVESTIGATIONAL. Prior Authorization Information Inpatient • For services described in this policy, precertification/preauthorization IS REQUIRED for all products if the procedure is performed inpatient. Outpatient • For services described in this policy, see below for products where prior authorization might be required if the procedure is performed outpatient. Outpatient Commercial Managed Care (HMO and POS) This is not a covered service. Commercial PPO and Indemnity This is not a covered service. Medicare HMO BlueSM This is not a covered service. Medicare PPO BlueSM This is not a covered service. CPT Codes / HCPCS Codes / ICD Codes Inclusion or exclusion of a code does not constitute or imply member coverage or provider reimbursement. Please refer to the member’s contract benefits in effect at the time of service to determine coverage or non-coverage as it applies to an individual member. 1 Providers should report all services using the most up-to-date industry-standard procedure, revenue, and diagnosis codes, including modifiers where applicable. CPT Codes CPT codes: Code Description 95803 Actigraphy testing, recording, analysis, interpretation and report (minimum of 72 hours to 14 consecutive days of recording) ICD Diagnosis Codes Investigational for all diagnoses. -

ACTIGRAPHY Wactisleep-BT Monitor Micro Motionlogger Watch Motionlogger Watch Motionwatch 8 Actiwatch Spectrum Somnowatch

Company ActiGraph Ambulatory Monitoring Inc CamNtech Philips Respironics SOMNOmedics America Inc Product Name ACTIGRAPHY wActiSleep-BT Monitor Micro Motionlogger Watch Motionlogger Watch MotionWatch 8 Actiwatch Spectrum SOMNOwatch www.ambulatory-monitoring. www.ambulatory-monitoring. www.somnomedics- Website www.actigraphcorp.com www.camntech.com www.philips.com/actigraphy com com diagnostics.com 1-year standard warranty; Cost/Warranty $299/1 year 1 year 1 year $750/2 years 2 years extended warranty available 3-axis solid state Miniaturized poly-silicone-surface Accelerometer accelerometer with digital Solid state triaxial Solid state triaxial MEMS – 3 axis Solid-state “piezoelectric” micromachined Technology filtering sensor (MEMS) 3.81 cm x 2.54 cm x 1.016 Product Dimensions 4.6 cm x 3.3 cm x 1.9 cm 3.6 cm x 3.6 cm x 1.2 cm 5.5 cm x 4.5 cm x 1.8 cm H 4.8 cm x 3.7 cm x 1.4 cm 4.5 cm x 4.5 cm x 1.6 cm cm Weight, Including 22 grams 30 grams 65 grams 16.8 grams 30 grams 30 grams Batteries and Wrist Band Rechargeable lithium Li-Ion-Accu, inbuilt, Batteries 1 DL2430 disposable coin cell 1 DL2450 disposable coin cell Common watch R2032 Lithium coin cell CR 2430 polymer rechargeable 1-year battery life (with continuous Battery Life 31 days 30+ days 30+ days 1 year 26+ days use at 1-minute epoch) Type of Memory Storage 2 GB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 4 MB nonvolatile 2 MB nonvolatile 8 MB internal storage card Recording Time at 1- 36 days—Activity plus 120 days 30+ days 30+ days 182 days 45 days Minute Sample Interval 4 channels