Swanage and Portland: Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swanage Area Forum Including Surrounding Villages

SWANAGE AREA FORUM INCLUDING SURROUNDING VILLAGES NEWSLETTER MARCH 2021 - No. 10 Welcome to the Swanage Area Forum and Swanage & Purbeck Development Trust March Newsletter. In these dark times, we can see the green shoots of Spring all around us, as the days lengthen and the increasing warmth and sunshine remind us that summer is not that far away. In this issue, you can see this reflected in the many uplifting contributions from our organisations and clubs throughout our communities, and the determination that this invisible Covid foe will not break us. I would also like to draw your attention to two particular items; firstly, as there is a ray of hope and cautious optimism appearing at the end of the very long Covid-19 tunnel, please read the important article on pages 2,3 and 4 from Dr Jason Clark of The Swanage Medical Practice with the latest Covid-19 update and the changes and possibilities for the near future. Secondly, you will see that The Swanage Area Forum will co-host a special Zoom People’s Assembly next Friday March 12th regarding The Dorset Local Plan Consultation. This public consultation comes to an end on March 15th, so If you would like to know more about the Dorset Plan and participate in the consultation process, even at this late stage, you can find details on Pages 16 and 17. Mel Norris, Chair Swanage Area Forum and Swanage & Purbeck Development Trustee [email protected] Photograph by Robert Field Photograph by Gwenda Yeomans Swanage Ambulance Car at the end of the road? The paramedic car which serves Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck villages, is in danger of being withdrawn by the end of March, according to a local reliable source. -

The Spinneys Studland • Dorset the Spinneys Swanage Road • Studland • Swanage • Dorset • BH19 3AE

The Spinneys Studland • Dorset The Spinneys Swanage Road • Studland • Swanage • Dorset • BH19 3AE Beautifully presented split level house in this sought after coastal location Accommodation Reception Hall • Sitting Room • Dining Room • Kitchen • Second Sitting Room Master Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom • Three further Bedrooms • Family Bathroom Integral Double Garage SaviIls Wimborne Wessex House, Wimborne Dorset, BH21 1PB [email protected] 01202 856800 Situation There is also a railway station at nearby Wareham with a a shower room with WC and an additional sitting room also The Spinneys is located on the outskirts of the immensely service between Weymouth and London as well as the with access to the rear garden. On the first floor are four popular seaside village of Studland with amenities including Heritage Railway link to the coastal resort of Swanage. bedrooms, the master bedroom and bedroom two having a post office, shop, public house, the well regarded Pig on lovely views out over the delightful front gardens and Ballard the Beach and of course easy access to sandy beaches and Description Down beyond. the sea offering excellent water sport opportunities. Nearby The Spinneys is a beautifully presented detached split level Accommodation towns include Swanage and Wareham, both of which offer village house with part rendered and stone elevations under a Please see floor plans. a good variety of shopping, educational and recreational tiled roof. The property was constructed about 30 years ago facilities. Sporting facilities include nearby golf courses at the for the present owners and has been maintained to a high Outside Isle of Purbeck Golf Club and the Dorset Golf & Country Club standard and is set within a large plot with both front and rear The property is approached from the village road via a tarmac and walking along the Dorset Jurassic Coastline a UNESCO gardens. -

Ompras Dorset

www.visit-dorset.com #visitdorset Bienvenido Nuestro pasado más antiguo vendrá a tu encuentro en Dorset, desde los acantilados jurásicos plagados de fósiles en los alrededores de Presentación de Dorset la romántica Lyme Regis hasta el imponente arco en piedra caliza Más información sobre cómo llegar hasta Dorset: ver p. 23. conocido como la Puerta de Durdle en la espectacular costa que ha sido declarada Patrimonio de la Humanidad. En el interior, Dorset Más lugares para visitar en Dorset: cuenta con acogedoras poblaciones conocidas tradicionalmente www.visit-dorset.com por sus mercados, ondulantes colinas de creta blanca en la parte Síguenos en: norte y el misterioso Gigante de Cerne Abbas. Vayas donde vayas tendrás consciencia del profundo sentido histórico de este condado, VisitDorset enmarcado por una fascinante belleza escénica. Descubre la colorida historia del Castillo de Highcliffe en Christchurch, visita el Puerto de #visitdorset Portland, donde tuvieron lugar las competiciones de vela de los Juegos Olímpicos y Paralímpicos de Londres en 2012, recorre los caminos OfficialVisitDorset de los acantilados en la Isla de Purbeck para disfrutar de magníficas VisitDorsetOfficial vistas de Old Harry Rocks o relájate en las interminables playas de la Bahía de Studland. Sal de picnic con la familia para pasar un día inolvidable en las resguardadas playas de Weymouth o Swanage, deja que el viento acaricie tu rostro en la rocosa playa de Chesil, o trepa por la empedrada Gold Hill en Shaftesbury para ver las privilegiadas vistas panorámicas del valle de Blackmore. Dorset te depara todo esto y más, incluyendo las brillantes luces de las cercanas Bournemouth y Poole y las rutas de senderismo del Parque Nacional de New Forest. -

Hydrogeological Field Guide to the Wessex Basin

Hydrogeological Field Guide to the Wessex Basin Technical Report IR/00/77 R Tyler-Whittle, P Shand, K J Griffiths and W M Edmunds This page is blank BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Natural Environment Research Council TECHNICAL REPORT IR/00/77 Hydrogeology Series Technical Report IR/00/77 Hydrogeological Field Guide to the Wessex Basin R Tyler-Whittle, P Shand, K J Griffiths and W M Edmunds This report was prepared for an EU BASELINE fieldtrip. Bibliographic Reference Tyler-Whittle R, Shand P, Griffiths K J and Edmunds W M, 2000 Hydrogeological Field Guide to the Wessex Basin British Geological Survey Report IR/00/77 NERC copyright 2000 British Geological Survey Keyworth, Nottinghamshire BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY KEYWORTH NOTTINGHAM NG12 5GG UNITED KINGDOM TEL (0115) 9363100 FAX (0115) 9363200 DOCUMENT TITLE AND AUTHOR LIST Hydrogeological Field Guide to the Wessex Basin R Tyler-Whittle, P Shand, K J Griffiths and W M Edmunds CLIENT CLIENT REPORT # BGS REPORT# IR/00/77 CLIENT CONTRACT REF BGS PROJECT CODE CLASSIFICATION Restricted SIGNATURE DATE SIGNATURE DATE PREPARED BY CO-AUTHOR (Lead Author) CO-AUTHOR CO-AUTHOR PEER REVIEWED BY CO-AUTHOR CHECKED BY CO-AUTHOR (Project Manager or deputy) CO-AUTHOR APPROVED BY CO-AUTHOR (Project Director or senior staff) CO-AUTHOR APPROVED BY OS Copyright (Hydrogeology acknowledged Group Manager) Assistant Director Layout checked by clearance (if reqd) BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG the BGS Sales Desk at the Survey headquarters, ☎ 0115-936 3100 Telex 378173 BGSKEY G Keyworth, Nottingham. The more popular maps and Fax 0115-936 3200 books may be purchased from BGS-approved stockists Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3LA and agents and over the counter at the Bookshop, Gallery ☎ 37, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, (Earth 0131-667 1000 Telex 727343 SEISED G Fax 0131-668 2683 Galleries), London. -

Portland Neighbourhood Plan: 1St Consultation Version Nov 2017

Neighbourhood Plan for Portland 2017-2031 1st Consultation Version Portland Town Council November 2017 Date of versions: 1st consultation draft November 2017 Pre-submission version Submission version Approved version (made) Cover photograph © Kabel Photography 1 Portland Neighbourhood Plan 1st Consultation Version Contents: Topic: page: Foreword 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Portland Now 5 3 The Strategic Planning Context 7 4 Purpose of the Neighbourhood Plan 12 5 The Structure of Our Plan 14 6 Vision, Aims and Objectives 15 7 Environment 18 8 Business and Employment 36 9 Housing 43 10 Transport 49 11 Shopping and Services 54 12 Community Recreation 58 13 Sustainable Tourism 67 14 Monitoring the Neighbourhood Plan 77 Glossary 78 Maps in this report are reproduced under the Public Sector Mapping Agreement © Crown copyright [and database rights] (2014) OS license 100054902 2 Foreword The Portland Neighbourhood Plan has been some time in preparation. Portland presents a complex and unique set of circumstances that needs very careful consideration and planning. We are grateful that the Localism Act 2012 has provided the community with the opportunity to get involved in that planning and to put in place a Neighbourhood Plan that must be acknowledged by developers. We must adhere to national planning policy and conform to the strategic policies of the West Dorset, Weymouth and Portland Local Plan. Beyond that, we are free to set the land use policies that we feel are necessary. Over the past three years much research, several surveys, lots of consultation and considerable discussion has been carried out by a working group of local people. -

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHXFW-5 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Dorset Coast is beautiful all year round but there are some even more spectacular sights around winter. Spend the festive season on the Dorset Coast, socialising and walking in this beautiful place. There’s something magical about walking in winter. Whether it’s the frosty footsteps, the clear crisp air, or the breathtaking views, it’s a wonderful time to go walking. Join our festive breaks and choose from a guided walking holiday in the company of one of our knowledgeable leaders. We pull out all the stops on our festive holidays, with fabulous food, lots of seasonal entertainment and great walks and activities. The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions. Each day three grades of walk will be offered. So wrap up warm, lace up your boots and go for an invigorating walk. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Wonderful meals – full selection at breakfast, your choice of picnic lunch, an excellent evening meal and plenty of festive treats • A programme of organised walks and activities www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • The services of experienced HF Holidays’ guides • A packed programme of evening activities offering something festive for everyone, including some old HF favourites • Any transport to and from the walks HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Enjoy Christmas or New Year at our new Country House at Lulworth Cove • Plenty of exercise to walk off the festive excesses • A choice of guided walks along the spectacular Dorset Coast • Just relax, soak up the party atmosphere, enjoy wonderful festive fare and leave all the organising to us • Evening activities include dancing, quizzes and carol evenings TRIP SUITABILITY The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions. -

Purbeck Ride ‘Out of Car Experience - Cycling in Purbeck’ Circular Route Around Purbeck - 47 Miles

Route 6 Purbeck Ride ‘Out of Car Experience - Cycling in Purbeck’ Circular route around Purbeck - 47 miles Durdle Door Corfe Castle Bluebell Woods Time needed: All day / weekend for entire route Can be ridden in smaller sections Grading: Difficult Several very steep hills. Purbeck Ride Section 2: Corfe Castle to Swanage Distance: 47 miles Climb this steep hill and turn left for East and Continue on the A351, past the National Trust West Lulworth enjoying the views from the top Visitor Centre, and the road to Studland. Take across Tyneham (from Whiteways viewpoint) A long distance route for the dedicated cyclist, 4 and to the sea 9 . encompassing stunning coastal views, beautiful rural the next left into Sandy Hill Lane . Pass under landscapes and interesting historic landmarks. the railway bridge, look right after going under Begin the long winding descent toward the village. the bridge and you will catch a glimpse of Corfe Look out for great views of the Castle on your right. Starting point: Wareham Quay Castle railway station, part of the steam line As you leave the army ranges, turn left towards Alternative starting points: Corfe Castle, Swanage, from Norden to Swanage. West Lulworth, Moreton and Bere Regis Lulworth Castle and villages. Time needed: All day/weekend for entire route or can Follow this winding lane for quite some time, Turn left at the next junction towards West Lulworth. be ridden in small sections. passing Sandyhills Farm, Woolgarston, Aitwood Farm (Note Lulworth Castle on the right which serves and ignoring all turnings off this road. 10 Degree of difficulty: Mainly on road, some very steep refreshments. -

Natural Hydraulic Fractures in the Wessex Basin, SW England: Widespread Distribution, Composition and History Alain Zanella, Peter Robert Cobbold, Tony Boassen

Natural hydraulic fractures in the Wessex Basin, SW England: widespread distribution, composition and history Alain Zanella, Peter Robert Cobbold, Tony Boassen To cite this version: Alain Zanella, Peter Robert Cobbold, Tony Boassen. Natural hydraulic fractures in the Wessex Basin, SW England: widespread distribution, composition and history. Marine and Petroleum Geology, Elsevier, 2015, 68 (Part A), pp.438-448. 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.09.005. insu-01200780 HAL Id: insu-01200780 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-01200780 Submitted on 18 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Natural hydraulic fractures in the Wessex Basin, SW England: widespread distribution, composition and history A. Zanella 1, 2 *, P.R. Cobbold 1 and T. Boassen 4 1Géosciences-Rennes (UMR-6118), CNRS et Université de Rennes 1, Campus de Beaulieu, 35042 Rennes Cedex, France 2L.P.G., CNRS UMR 6112, Université du Maine, Faculté des Sciences, 72085 Le Mans Cedex 9, France 4 Statoil ASA Research Centre, NO-7005 Trondheim, Norway *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Bedding-parallel veins of fibrous calcite ('beef') are historical in the Wessex Basin. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Notes to Accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018

Notes to accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018 SUMMARY Travel to Lyme Regis; lunch ad hoc; 3:00 pm visit Lyme Regis Museum for Monday 01-Oct Museum tour with Chris Andrew, the Museum education officer and fossil walk guide; Arrive at our Weymouth hotel at approx. 5-5.30 pm Tuesday 02 -Oct No access to beaches in morning due to tides. Several stops on Portland and Fleet which are independent of tides Visit Lulworth Cove and Stair Hole; Poss ible visit to Durdle Door; Lunch at Wednesday 03-Oct Clavell’s Café, Kimmeridge; Visit to Etches Collection, Kimmeridge (with guided tour by Steve Etches). Return to Weymouth hotel. Thur sday 04 -Oct Burton Bradstock; Charmouth ; Bowleaze Cove Beaches are accessible in the morning. Fri day 05 -Oct Drive to Lyme Regis; g uided beach tour by Lyme Regis museum staff; Lunch ad hoc in Lyme Regis; Arrive Ledbury/Malvern in the late afternoon PICK-UP POINTS ( as per letter from Easytravel) Monday 1 Oct. Activity To Do Worcester pick-up Depart Croft Rd at 08.15 Barnards Green pick-up 08.45 Malvern Splash pick-up 08.50 Colwall Stone pick-up 09.10 Pick-ups and travel Ledbury Market House pick-up 09.30 to Lyme Regis Arrive Lyme Regis for Lunch - ad hoc 13.00 – 14.00 Visit Lyme Regis Museum where Chris Andrew from the Museum staff will take us for a tour of 15.00 to 16.30 the Geology Gallery. Depart Lyme Regis for Weymouth 16.30 Check in at Best Western Rembrandt Hotel, 17.30 Weymouth At 6.15pm , we will meet Alan Holiday , our guide for the coming week, in the Garden Lounge of the hotel prior to dinner. -

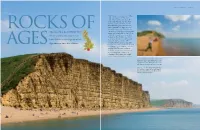

Agesalmost As Old As Time Itself, the West Dorset Coastline Tells Many

EXPLORING BRITAIN’ S COASTLINE H ERE MAY BE DAYS when, standing on the beach at TCharmouth, in the shadow of the cliffs behind, with the spray crashing against the shore and the wind whistling past your ears, it is ROCKS OF hard to imagine the place as it was 195 million years ago.The area was Almost as old as time itself, the west a tropical sea back then, teeming with strange and wonderful creatures. It is Dorset coastline tells many stories. a difficult concept to get your head around but the evidence lies around Robert Yarham and photographer Kim your feet and in the crumbling soft mud and clay face of the cliffs. AGES Disturbed by the erosion caused by Sayer uncover just a few of them. the spray and wind, hundreds of small – and very occasionally, large – fossils turn up here.The most common fossils that passers-by can encounter are ammonites (the curly ones), belemnites (the pointy ones); and, rarely, a few rarities surface, such as ABOVE Locals and tourists alike head for the beaches by Charmouth, where today’s catch is a good deal less intimidating than the creatures that swam the local seas millions of years ago. MAIN PICTURE The layers of sand deposited by the ancient oceans can be clearly seen in the great cliffs of Thorncombe Beacon (left) and West Cliff, near Bridport. A37 A35 A352 Bridport A35 Dorchester Charmouth A354 Lyme Regis Golden Cap Abbotsbury Osmington Mills Swannery Ringstead Bay The Fleet Weymouth Chesil Beach Portland Harbour Portland Castle orth S N I L 10 Miles L Isle of Portland O H D I V A The Bill D icthyosaurs or plesiosaurs – huge, cottages attract hordes of summer predatory, fish-like reptiles that swam visitors.They are drawn by the the ancient seas about 200 million picturesque setting and the famous years ago during the Jurassic period. -

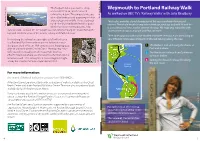

Weymouth to Portland Railway Walk Uneven Descent to Join the Disused Railway Line Below

This footpath takes you down a steep, Weymouth to Portland Railway Walk uneven descent to join the disused railway line below. This unique landscape As walked on BBC TV’s ‘Railway Walks’ with Julia Bradbury altered by landslips and quarrying is rich in line along dotted fold archaeology and wildlife. Keep a look out This leaflet provides a brief description of the route and main features of for the herd of feral British Primitive goats interest. The whole length is very rich in heritage, geology and wildlife and this View from the Coast Path the Coast from View which have been reintroduced to help is just a flavour of what can be seen on the way. We hope you enjoy the walk control scrub. To avoid the steep path you can continue along the Coast Path at the and that it leads you to explore and find out more. top with excellent views of the weares, railway and Purbeck coast. The 6 mile (approx.) walk can be divided into three sections, each one taking in On reaching the railway line turn right as left will take you very different landscapes and parts of disused railways along the way. to a Portland Port fence with no access. Follow the route along past Durdle Pier, an 18th century stone shipping quay START WEYMOUTH 1 The Rodwell Trail and along the shores of with an old hand winch Derrick Crane. Passing impressive Portland Harbour cliffs you will eventually join the Coast Path down to 2 The Merchants’ railway from Castletown Church Ope Cove where you can return to the main road or to Yeates Incline continue south.