Native People Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buffy Sainte-Marie Best of the Vanguard Years Mp3, Flac, Wma

Buffy Sainte-Marie Best Of The Vanguard Years mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Best Of The Vanguard Years Country: UK Released: 2004 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1110 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1297 mb WMA version RAR size: 1397 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 787 Other Formats: AIFF WAV VQF MP3 AAC TTA AHX Tracklist 1 A Soulful Shade Of Blue 2:15 2 Summer Boy 2:38 3 The Universal Soldier 2:16 4 Better Found Out For Yourself 2:12 5 Cod'dine 5:03 6 He's A Keeper Of The Fire 2:58 7 Take My Hand For A While 2:30 8 Groundhog 2:15 9 The Circle Game 2:52 10 My Country 'Tis Of Thy People You're Dying 6:45 11 Many A Mile 2:42 12 Until It's Time For You To Go 2:28 13 Rolling Log Blues 3:27 14 God Is Alive,Magic Is Afoot 4:49 15 Gues Who I Saw In Paris 2:23 16 The Piney Wood Hills 3:04 17 Now That The Buffalo's Gone 2:47 18 Cripple Creek 1:45 19 I'm Gonna Be A Country Girl Again 2:55 20 The Vampire 2:06 21 Little Wheel Spin And Spin 2:26 22 Winter Boy 3:28 23 Los Pescadores (The Fisherman) 2:03 24 Sometimes When I Get To Thinkin' 2:57 25 Bird On A Whire 3:28 26 God Bless The Child 3:35 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Vanguard Records Copyright (c) – Vanguard Records Copyright (c) – Ace Records Ltd. -

Buffy Sainte-Marie Soldier Blue Mp3, Flac, Wma

Buffy Sainte-Marie Soldier Blue mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Stage & Screen Album: Soldier Blue Country: UK Released: 1971 Style: Soundtrack, Theme MP3 version RAR size: 1978 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1233 mb WMA version RAR size: 1722 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 423 Other Formats: MP2 RA MP1 AIFF XM AU VOX Tracklist A Soldier Blue 3:26 B Moratorium (Bring Our Brothers Home) 4:00 Companies, etc. Distributed By – RCA Records Manufactured By – RCA Limited Published By – Cyril Shane Music – A-Side Published By – Caleb Music – B-Side Credits Producer – Jack Nietzsche* Written-By, Producer – Buffy Sainte-Marie Notes This version has a solid centre. A similar version exists with a push-out centre. This version has 'Brothers' printed in the title for track B instead of 'Brother'. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Label A-side): AGBKS 0531 Matrix / Runout (Label B-side): AGBKS 0532 Matrix / Runout (A: Machine stamped): AGBKS-0531-1 Matrix / Runout (B: Machine stamped): AGBKS-0532-1 Rights Society (B-Side): MCPS Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Soldier Blue (7", RCA RCA 2081 Buffy Sainte-Marie RCA 2081 UK 1971 Promo) Victor Soldier Blue (7", RCA RCA 2081 Buffy Sainte-Marie RCA 2081 UK 1971 Single, Sol) Victor Soldier Blue (7", SRCA-88509 Buffy Sainte-Marie Jugoton SRCA-88509 Yugoslavia 1971 Single) Soldier Blue (This FBS 17 Buffy Sainte-Marie Is My Country) (7", PRT FBS 17 UK Unknown Single) Soldier Blue (7", RCA RCA 2081 Buffy Sainte-Marie RCA 2081 UK 1971 Single, Sol) Victor -

Buffy Sainte-Marie It's My Way! Mp3, Flac, Wma

Buffy Sainte-Marie It's My Way! mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: It's My Way! Country: US Released: 1964 Style: Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1363 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1222 mb WMA version RAR size: 1510 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 977 Other Formats: RA ADX AU AUD TTA XM APE Tracklist Hide Credits Now That The Buffalo's Gone A1 2:45 Bass – Art Davis A2 The Old Man's Lament 3:55 Ananias A3 2:35 Adapted By – Buffy Sainte-Marie A4 Mayoo Sto Hoon 1:19 A5 Cod'ine 5:01 A6 Cripple Creek 1:45 A7 The Universal Soldier 2:15 B1 Babe In Arms 2:30 He Lived Alone In Town B2 4:35 Guitar [2nd] – Patrick Sky B3 You're Gonna Need Somebody On Your Bond 2:45 B4 The Incest Song 4:11 B5 Eyes Of Amber 2:16 B6 It's My Way 3:29 Credits Guitar, Vocals – Buffy Sainte-Marie Written-By – Buffy Sainte-Marie (tracks: A1, A5, A7 to B2, B4 to B6) Notes Slightly different label variation. This copy says " "Stereolab" on Gold label Sleeve with upper band slightly different too in colours and contrasts Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Matrix Label side One): XSV 06416 Matrix / Runout (Matrix Label Side Two): XSV 06417 Matrix / Runout (Runout stamped side one): VSD-79142A XSV-06416-1E Barcode (Runout stamped side two): VSD-79142B XSV-06417-1C Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year It's My Way! (LP, VSD-79142 Buffy Sainte-Marie Vanguard VSD-79142 US 1964 Album) It's My Way! (LP, VSD-79142 Buffy Sainte-Marie Vanguard VSD-79142 US Unknown Album) It's My Way! (LP, VSD-79142 Buffy Sainte-Marie -

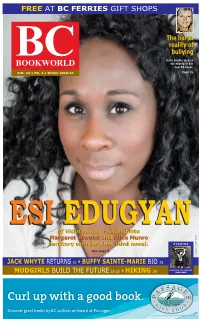

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Catalogue of Canadian Women Empowered by Music 1

Catalogue of Canadian Women Empowered by Music Who is in this catalogue? ...women empowered by music, women who empowered others through music, and women who were trailblazers in music. You will find composers, singers, educators, songwriters and activists, from every era and every style of music...but the catalogue is not complete! Here’s where YOU come in! See an entry for your favourite artist which needs a longer entry? Send us an expanded version! (limit: 200 words). Know a musician who is not even in the catalogue yet? Write an entry send it to: [email protected] Name Dates Category Career Highlights Listening Links Active Norma Abernethy 1930’s Performer Norma Abernathy was a pianist from Vancouver, British http://www.thecanadianencycl (1914-1973) - Columbia. She is best known as an accompanist and opedia.ca/en/article/norma- 1940’s soloist on radio stations such as CNRV and CBR, and as abernethy-emc/ a pianist with the Vancouver Chamber Orchestra and the Victoria Symphony Orchestra. Lydia Adams 1980s- Conductor Lydia Adams was born in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia and “Sing all ye https://www.thecanadianencycl (1953- ) Accompan completed her training at Mount Allison University in New joyful: the opedia.ca/en/article/lydia- ist Brunswick and the Royal College of Music in London, works of Ruth adams-emc/ Arranger England. She worked as an accompanist for the Elmer Watson Iseler Singers in the 1980s and early 1990s, and in 1997 Henderson” http://www.elmeriselersingers. she became the choir’s conductor and music director. Dr. com/lydia_adams.htm Adams was also the conductor and artistic director of the Amadeus Choir, and commissioned and premiered many works by Canadian composers. -

Buffy Sainte-Marie Tansi, Boozhoo, Hello. Welcome to the National

Buffy Sainte-Marie Tansi, Boozhoo, Hello. Welcome to the National Music Centre’s Speak Up exhibition, celebrating the voices of InDigenous trailblazers who’ve brought about social change through their music. Buffy Sainte-Marie is a living legenD anD a tireless aDvocate for InDigenous rights and freedoms. She is an innovative artist, educator and disruptor of the status quo who is always moving herself and society forwarD. Thought to be born in 1941 to Cree parents on the Piapot Cree First Nation reserve in Saskatchewan, Buffy was adopted as a child by a Massachusetts family of Mi’gmaw descent. She has since spent her whole life creating while trailblazing. She playeD piano as a chilD anD as a teenager took up guitar anD started composing songs. After completing high school she attended the University of Massachusetts, where she stuDieD philosophy with an Asian focus, anD eDucation. She receiveD a Bachelor’s Degree in 1962. Buffy began performing her songs in coffeehouses During her college years anD after graduation, she moveD to New York City anD became part of the Bohemian art scene. Much praise within the New York scene led to a contract with Vanguard Records, and to the release of her first album, It’s My Way, in 1964. Many of her lyrics from her first two albums, incluDing Many a Mile from 1965, aDDresseD the plight of Indigenous people. Particularly “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” and “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People, You’re Dying.” Her writing gained mainstream attention for her themes of war anD justice. -

78Periodico Di Hunkapi · · · · · · · · · · · · · · Associazione Culturale Per La Divulgazione Delle Tradizioni De

Tariffa Regime Libero: “Poste Italiane S.p.A. - Spedizione in Abbonamento postale - 70% - DCB Genova” - Anno XXI - Numero 2 78 P P E E R R I L O A D I D C I O V U D L I G H A U Z N I O K N A E P I D · E · L · L · E · · T · R · A · D · · I Z · I · O · N A I D S S E O G C L I I A I N Z I D O I N A E N I C D U ’ L A T M U E R R A I L C A E 2 “Le donne donano la vita, attraverso di loro avviene lo sviluppo, hanno una re - e sponsabilità speciale per proteggere l l’acqua”. Sono le prime parole dell’av - vocato Michelle Cook, quando si è se - Periodico di Hunkapi Associazione culturale per la a duta al tavolo della conferenza “Water divulgazione delle tradizioni i is Life”, organizzata da Hunkapi, in col - degli Indiani d’America. laborazione con l’Associazione Il Cer - Aut. Trib. Genova n° 16/97 del 21.5.97 r chio, una sera di ottobre a Genova. Hunkapi Editore Raccontiamo di loro e di quello che Direzione: Via dei Partigiani, 15/2 stanno facendo, in un tour che ha por - 16021 Bargagli (GE) o tato la parola dei Nativi in giro per l’Eu - Redazione ropa. E anche se la costruzione Via Ravasco, 1/5A - 16123 Genova t dell’oleodotto è terminata, ora come Telefono 3883752946 www.hunkapi.it i mai è necessario continuare a lottare. -

Artist / Bandnavn Album Tittel Utg.År Label/ Katal.Nr

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP KOMMENTAR A 80-talls synthpop/new wave. Fikk flere hitsingler fra denne skiva, bl.a The look of ABC THE LEXICON OF LOVE 1983 VERTIGO 6359 099 GER LP love, Tears are not enough, All of my heart. Mick fra den første utgaven av Jethro Tull og Blodwyn Pig med sitt soloalbum fra ABRAHAMS, MICK MICK ABRAHAMS 1971 A&M RECORDS SP 4312 USA LP 1971. Drivende god blues / prog rock. Min første og eneste skive med det tyske heavy metal bandet. Et absolutt godt ACCEPT RESTLESS AND WILD 1982 BRAIN 0060.513 GER LP album, med Udo Dirkschneider på hylende vokal. Fikk opplevd Udo og sitt band live på Byscenen i Trondheim november 2017. Meget overraskende og positiv opplevelse, med knallsterke gitarister, og sønnen til Udo på trommer. AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 GER LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. HEADLINES AND DEADLINES – THE HITS WARNER BROS. A-HA 1991 EUR LP OF A-HA RECORDS 7599-26773-1 Samlealbum fra de norske gutta, med låter fra perioden 1985-1991 AKKERMAN, JAN PROFILE 1972 HARVEST SHSP 4026 UK LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske progbandet Focus. Akkermann med klassisk gitar, lutt og et stor orkester til hjelp. I tillegg rockere som AKKERMAN, JAN TABERNAKEL 1973 ATCO SD 7032 USA LP Tim Bogert bass og Carmine Appice trommer. -

Ace Catalogue 2014

ace catalogue 2014 ACE • BIG BEAT • BGP • CHISWICK • GLOBESTYLE • KENT • KICKING MULE • SOUTHBOUND • TAKOMA • VANGUARD • WESTBOUND A alphabetic listing by artist 2013’s CDs and LPs are presented here with full details. See www.acerecords.com for complete information on every item. Artist Title Cat No Label Nathan Abshire With His Pine Master Of The Cajun Accordion: CDCHD 1348 Ace Grove Boys & The Balfa Brothers The Classic Swallow Recordings Top accordionist Nathan Abshire at his very best in the Cajun honky-tonk and revival eras of the 1960s and 1970s. Pine Grove Blues • Sur Le Courtableau • Tramp Sur La Rue • Lemonade Song • A Musician’s Life • Offshore Blues • Phil’s Waltz • I Don’t Hurt Anymore • Shamrock • If You Don’t Love Me • Service Blues • Partie A Grand Basile • Nathan’s Lafayette Two Step • Let Me Hold Your Hand • French Blues • La Noce A Josephine • Tracks Of My Buggy • J’etais Au Bal • Valse De Kaplan • Choupique Two Step • Dying In Misery • La Valse De Bayou Teche • Games People Play • Valse De Holly Beach • Fee-Fee Pon-Cho Academy Of St Martin-in-the-Fields Amadeus - Special Edition: FCD2 16002 (2CD) Ace Cond By Sir Neville Marriner The Director’s Cut Academy Of St Martin-in-the-Fields The English Patient FCD 16001 Ace Cond By Harry Rabinowitz Ace Of Cups It’s Bad For You But Buy It! CDWIKD 236 Big Beat Act I Act I CDSEWM 145 Southbound Roy Acuff Once More It’s Roy Acuff/ CDCHD 988 Ace King Of Country Music Roy Acuff & His Smokey Sings American Folk Songs/ CDCHD 999 Ace Mountain Boys Hand-Clapping Gospel Songs Cannonball -

2011 Catalog 5/14 Pm

Welcome to our 2011 Spring Music Catalog! To get started, click on the Bookmark Tab in the upper left corner of this document. If you don’t see this option go to View>Navigation Tabs>Bookmarks on your PC or Windows >Bookmarks on a MAC. Once your bookmark tab is functioning you will see the headings of the catalog. A plus sign means there are titles within that main heading. Click on any word to get to that location in the catalog as shown in the example below. Please familiarize yourself with Adobe Reader’s toolbox. Pages + Flute Music can be re-sized for easier viewing by using the zoom tool or per- Bryan Akipa centage field. You can move each page manually with the hand Scott August tool. Arrows at the top of the document advance pages forward Jeff Ball or backward. Adobe Reader has a HELP menu that will open in a + Contemporary Music separate pane right next to this document that will show you how Susan Aglukark to customize your tools and answer questions. Having trouble Ah Nee Mah viewing our catalog? Please call us at 1-800-688-0187. We are Airo always glad to help! Or email us at the address below. + Pow Wow Glen Ahhaitty Please be aware that our wholesale catalog can never be up to Walter Ahhaitty Bad Moon date because of the quantity and frequency of new releases. Our website has a New Release section on it that is always up to date with sounds clips so be sure to check it before you place an order. -

Eric Carmen/2Nd Career Happiness

.,... MAP, 15 197e ERIC CARMEN/2ND CAREER HAPPINESS Rack's Share Of Business Cut To 40% - Shift To Retail NEC's 16th Confab: Virtual `Smorgasbord' Brunswick Trial Ends With Four Convicted CBS, WCI Record Divisions Analyzed New Carly Simon LP May Lead To Some Gigs Harvey Cooper Named e.+111 Senior VP, Mkt. At 20th Breaking New Acts: Key To The Future (Ed) www.americanradiohistory.com "Disco Lady"is just -shy Crossover stations are of that mark right r_ovl less literally pouring in; Johnnie Also available on ape than a month after its Taylor easily has Johnnie Taylor Eargasm release. That makes it one t_ze biggest including: Disco Lady Don't Touch Her Body (If Can't you buch Her Mu ) y s Getön tt/You're The Mooning Best In The World of the fastest-se_incq singles hit cf _pis Out Of Lies in Columbia Recorc.s' _-1istory. career. It's in the top ten in almost "Disco Lady" every major market, arid from Johnnie hitting the number Taylor's debut Columbia one spot on many album, R&R stations. :',. ,. MANAGEMENT: TAG ENTERPRISES, 731 R.L. SOUTH THORNTON FREEWAY, DALLAS, TEXAS 7E203, 214-941-3333 COLOMBIO.,' Q MARLAS REG. ©19)6 CBS INC www.americanradiohistory.com THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY BQX6, CASHVOLUME XXXVII - NUMBER 42 - March 1976 VCVr7t7C 1 President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Executive Vice President cath box editorial Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief Key To The Future IAN DOVE Breaking New Acts -- East Coast Editorial Director One record executive recently responded to the question of "How's New York GARY COHEN business?" by saying, "we had our best quarter ever, our best year in history, BOB KAUS PHIL DIMAURO gold records galore, but we didn't break any new artists." It is that 'but' that RUDOLPH ERIC might come back to haunt the house of hits if action isn't taken now.