El Oído Pensante, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Ulrich Buch Engl. Ulrich Buch Englisch

Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik First edition 2012 Published by Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax +49-[0] 2268-1813) www.stockhausen-verlag.com All rights reserved. Copying prohibited by law. O c Copyright Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 Translation: Jayne Obst Layout: Kathinka Pasveer ISBN: 978-3-9815317-0-1 STOCKHAUSEN A THEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION BY THOMAS ULRICH Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remark .................................................................................................. VII Preface: Music and Religion ................................................................................. VII I. Metaphysical Theology of Order ................................................................. 3 1. Historical Situation ....................................................................................... 3 2. What is Music? ............................................................................................. 5 3. The Order of Tones and its Theological Roots ............................................ 7 4. The Artistic Application of Stockhausen’s Metaphysical Theology in Early Serialism .................................................. 14 5. Effects of Metaphysical Theology on the Young Stockhausen ................... 22 a. A Non-Historical Concept of Time ........................................................... 22 b. Domination Thinking ................................................................................ 23 c. Progressive Thinking -

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music Selected, with Introduction, Commentary, and Notes by Richard Leppert. Translations by Susan H. Gillespie and others Contents Preface and Acknowledgments Translator's Note Abbreviations Introduction by Richard Leppert 1. LOCATING MUSIC: SOCIETY, MODERNITY, AND THE NEW Commentary by Richard Leppert Music, Language, and Composition (1956) Why Is the New Art So Hard to Understand? (1931) On the Contemporary Relationship of Philosophy and Music (1953) On the Problem of Musical Analysis The Aging of the New Music (1955) The Dialectical Composer (1934) 2. CULTURE, TECHNOLOGY, AND LISTENING Commentary by Richard Leppert The Radio Symphony (1941) The Curves of the Neddle (1927/1965) The Form of the Phonograph Record Opera and the Long-Playing Record (1969) On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening (1938) Little Heresy (1965) 3. MUSIC AND MASS CULTURE Commentary by Richard Leppert What National Socialism Has Done to the Arts (1945) On the Social Situation of Music (1932) On Popular Music [With the assistance of George Simpson] (1941) On Jazz (1936) Farewell to Jazz (1933) Kitsch (c. 1932) Music in the Background (c. 1934) 4. COMPOSITION, COMPOSERS, AND WORKS Commentary by Richard Leppert Late Style in Beethoven (1937) Alienated Masterpiece: The Missa Solemnis (1959) Wagner's Relevance for Today (1963) Mahler Today (1930) Marginalia on Mahler (1936) The Opera Wozzeck (1929) Toward an Understanding of Schoenberg (1955/1967) Difficulties (1964, 1966) Bibliography Introduction Richard Leppert Life and Works Adorno was a genius; I say that without reservation. [He] had a presence of mind, a spontaneity of thought, a power of formulation that I have never seen before or since. -

Musik Gibt Es Nicht. Musik Soll Entstehen Im Kopf Des Zuschauers / Zuhörers

Musik gibt es nicht. Musik soll entstehen im Kopf des Zuschauers / Zuhörers. Dieter Schnebels Instrumentales Theater von Volker Straebel1 Als der Komponist Dieter Schnebel 1966 bei den Darmstädter Ferienkursen für Neue Musik einen Vortrag über Sichtbare Musik2 hielt, konnte er sich eines Publikums gewiss sein, dessen Begriff davon, was Musik eigentlich sei, sich nicht auf das Akustische beschränkte. Die Diskussionen auf diesen jährlichen Treffen der europäischen Nachkriegsavantgarde waren lange geprägt gewesen von den mathematischen und physikalischen Entwürfen, die die serielle und Elektronische Musik hervorgebracht hatten. Diesen lag die Idee zugrunde, alle klanglichen und zeitlichen Aspekte eines Musikwerkes in parametrisierbaren Größen zu beschreiben und sie in Anlehnung an die Zwölftonkomposition mittels Zahlenreihen kompositorisch zu bestimmen. Pierre Boulez und Karlheinz Stockhausen wurden zu Protagonisten einer Komponistengeneration, die neben Tonhöhe, Dauer und Lautstärke bald auch komplexere musikalische Zusammenhänge wie Klangfarbe, Ereignisdichte oder Raumdisposition seriell organisierte. Aus der Rückschau wirken – anders als in ihrer Entstehungszeit – die frühen seriellen Kompositionen wie beispielsweise Karlheinz Stockhausens Zeitmaße für Blasquintett von 1956 weniger skandalös und kaum ausschließlich mathematisch determiniert. Die musikalische Erfahrung dürfte heute die kompositionstechnische Würdigung der hier bis zu fünf gleichzeitig ablaufenden Zeitschichten überwiegen. Dennoch ist offensichtlich, dass sich die ästhetische -

Luigi Nono Prometeo, Tragedia Dell'ascolto LUIGI NONO (1924–1990)

contemporary Luigi Nono Prometeo, Tragedia dell'ascolto LUIGI NONO (1924–1990) PROMETEO, TRAGEDIA DELL’ascOLTO (1981/1985) for singers, speakers, chorus, solo strings, solo winds, glasses, orchestral groups, and live electronics Arrangement of texts by Massimo Cacciari SACD 1 1 I. PROLOGO 20:07 2 II. ISOLA 1° 23:06 3 III. ISOLA 2° a) IO–PROMETEO 18:03 4 b) HÖLDERLIN 08:10 total time 69:38 SACD 2 1 c) STASIMO 1° 07:48 2 IV. INTERLUDIO 1° 06:41 3 V. TRE VOCI a 12:05 4 VI. ISOLA 3°– 4°– 5° 17:10 5 VII. TRE VOCI b 06:48 6 VIII. INTERLUDIO 2° 05:01 7 IX. STASIMO 2° 08:56 Peter Hirsch, Luigi Nono (May 1986, Köln) total time 64:54 3 Petra Hoffmann, Monika Bair-Ivenz, soprano Solistenensemble des Philharmonischen Orchesters Freiburg Susanne Otto, Noa Frenkel, alto Hubert Mayer, tenor Sigrun Schell, Gregor Dalal, speakers Solistenensemble des SWR Sinfonieorchesters Baden-Baden und Freiburg Solistenchor Freiburg electronic realization: EXPERIMENTALSTUDIO für akustische Kunst e. V., Monika Wiech, Elisabeth Rave, Svea Schildknecht, soprano former EXPERIMENTALSTUDIO der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung Birgitta Schork, Evelyn Lang, Judith Ritter, alto des Südwestrundfunks e. V. Thomas Gremmelspacher, Klaus Michael von Bibra, Martin Ohm, tenor Uli Rausch, Matthias Schadock, Philipp Heizmann, bass André Richard, director, chorus master, artistic coordination, spatial sound conception, sound director ensemble recherche Reinhold Braig, Joachim Haas, Michael Acker, sound directors Bernd Noll, sound technician Martin Fahlenbock, flutes Shizuyo Oka, clarinets Barbara Maurer, viola Peter Hirsch, 1st conductor Lucas Fels, violoncello Kwamé Ryan, 2nd conductor Mike Svoboda, alto trombone, euphonium, tuba Ulrich Schneider, contrabass Christian Dierstein, Klaus Motzet, Jochen Schorer, glasses 4 5 PRÄAMBEL ANSPRUCH (UND) BESCHEIDENHEIT Luigi Nonos »Prometeo« im Aufbruch zu neuen Verhältnissen D Luigi Nono hat fast sein gesamtes Spätwerk in Zusammenarbeit mit dem EXPERI- MENTALSTUDio des SWR realisiert. -

Lexikon Neue Musik Inhalt

Jörn Peter Hiekel ∙ Christian Utz (Hrsg.) Lexikon Neue Musik Inhalt Artikelverzeichnis VII Einleitung IX (Jörn Peter Hiekel / Christian Utz) I. Themen 1 Die Avantgarde der 1950er Jahre und ihre zentralen Diskussionen (Ulrich Mosch) 3 2 Ein Sonderweg? Aspekte der amerikanischen Musikgeschichte im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert (Wolfgang Rathert) 17 3 Auf der Suche nach einer befreiten Wahrnehmung. Neue Musik als Klangorganisation (Christian Utz) 35 4 Angekommen im Hier und Jetzt? Aspekte des Weltbezogenen in der Neuen Musik (Jörn Peter Hiekel) 54 5 Ästhetische Pragmatiken analoger und digitaler Musikgestaltung im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert (Elena Ungeheuer) 77 6 Raumkomposition und Grenzüberschreitungen zu anderen Kunstbereichen (Christa Brüstle) 88 7 Zwischenklänge, Teiltöne, Innenwelten: Mikrotonales und spektrales Komponieren (Lukas Haselböck) 103 8 Geistliche, spirituelle und religiöse Perspektiven in der Musik seit 1945 (Jörn Peter Hiekel) 116 9 Verflechtungen und Reflexionen. Transnationale Tendenzen neuer Musik seit 1945 (Christian Utz) 135 II. Lexikon Artikel von A bis Z 157 Anhang Siglenverzeichnis 636 Autorinnen und Autoren 637 Personen- und Werkregister 638 Sachregister 670 IX ten zuvor herunterzuspielen und einseitig das Bild eines »Avantgarde-Hauptstroms« vorauszusetzen. Angesichts solcher und ähnlicher Erwägungen geht es im vorliegenden Lexikon Neue Musik um den in unter schiedliche Darstellungsformate und Teilthemen aufgefächerten Versuch, Simplifizierungen, Klischees, Einseitigkeiten und »blinde Flecken« in bisherigen Be- Einleitung schreibungsansätzen in Frage zu stellen bzw. zu korrigie- ren. Das Ziel dieses Handbuchs liegt somit nicht zuletzt darin, sich der Musik des 20. und 21. Jh.s in ihrer erheb- Verallgemeinerungen erweisen sich nicht selten als kunst- lichen Pluralität von Tendenzen, Kriterien, Phänomenen fremd. Auch der Umgang mit Entwicklungen und Ideen und Intentionen zu nähern, aber auch in ihren Widersprü- in der Musik hat dies oft genug gezeigt. -

Johannes Picht Laudatio Für Dieter Schnebel Zur Verleihung Des

Johannes Picht Laudatio für Dieter Schnebel Zur Verleihung des Sigmund- Freud- Kultur- Preises 2011 der DPV und der DPG Dieter Schnebel und die Psychoanalyse (für „Musik & Ästhetik“) Im Juni 2011 wurde Dieter Schnebel der Sigmund-Freud-Kulturpreis verliehen.1 Die Auszeich- nung macht darauf aufmerksam, dass Schnebel sich über weite Strecken seines Lebens von der Psychoanalyse hat begleiten lassen und dass hiervon wichtige Impulse für sein Werk und seine theoretischen Konzeptionen ausgegangen sind. Anlass genug, diese Einflüsse nachzu- zeichnen und aus Sicht eines Psychoanalytikers darauf zu antworten. Der 70-jährige Schnebel hat im Jahr 2000, als ihm der Tod in Gestalt eines Herzinfarkts schon begegnet war, seine eigene Vita als Kunstwerk gestaltet. Entstanden ist nicht eine Selbststili- sierung, sondern das Protokoll eines Eingebrachtseins in die Zeit und Geformtwerdens aus ihr, eine Spurenschrift des Sichereignens und Zusammentreffens. Unter dem Titel Signatur finden sich hier sogenannte Lebensblätter: eine Collagenfolge aus bunten, sich verflechten- den Linien, Namen, Bildern, Textausschnitten und Partiturschnipseln, ein – wie er dazu schreibt - Versuch, die Unterschrift des Lebens zeichnerisch bildhaft zu symbolisieren.2 Blättert man in diesem Lebenslaub, dann entsteht im Kopf eine Polyphonie, nicht hörbar, aber doch Musik. Dass Musik nicht nur das Hörbare oder gar nur das zu Gehör Gebrachte umfasst, sondern alles Bewegte und in Bewegung Bringende in und aus der Welt, in und aus den Köpfen und Leibern der an ihr, der Musik wie der Welt, Beteiligten, und dass Musik die an ihr Beteiligten zu Teilen und einander Zu-Teilenden werden lässt – diesen Horizont hatte 1 Der Sigmund-Freud-Kulturpreis wird gemeinsam von den beiden großen deutschen psychoanalytischen Fachgesellschaften (Deutsche Psychoanalytische Gesellschaft und Deutsche Psychoanalytische Vereinigung) alle zwei Jahre an Nichtpsychoanalytiker verliehen, die die Psychoanalyse in kreativ-kritischer Weise aufnehmen und verwenden. -

Aalborg Universitet Experimental Improvisation

Aalborg Universitet Experimental improvisation practise and notation. Addenda 2000- Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Bergstrøm-Nielsen, C. (2015). Experimental improvisation practise and notation. Addenda 2000-: Pdf edition. Intuitive Music Homepage. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: juni 19, 2017 EXPERIMENTAL IMPROVISATION PRACTISE AND NOTATION. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY. by Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen. This is a pdf version. Please note that there is both the "old" department, 1945-1999 – and addenda for since then. Two separate volumes. The html editions may be slightly more updated. They can be found at http:/www.intuitivemusic.dk/iima/cbn.htm Please note that the hyperlinks in this version may not work because the document is converted from html. -

Free Improvisation As a Performance Technique: Group Creativity and Interpreting Graphic Scores

Free Improvisation as a Performance Technique: Group Creativity and Interpreting Graphic Scores Edward NEEMAN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree, The Juilliard School May 2014 2014 Edward Neeman This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. ABSTRACT The late 1950s and 1960s saw the formation of groups of musicians devoted to free improvisation. These groups deliberately excluded pre-existing musical idioms and focused on the nature of improvisation and the processes involved in spontaneously inventing music and interacting as a group. The history, recordings, and writings of this free improvisation movement is a valuable source for prospective improvisers and demonstrates that free improvisation can be a serious discipline capable of developing meaningful and powerful musical discourse. The techniques that its practitioners developed to stimulate innovation and to explore the interactive possibilities of group creativity can be used in many musical and interdisciplinary applications. The interpretation of indeterminate graphic scores is one such application. Classical musicians are particularly suited to meeting the interpretational challenges of these works, and an openness to improvisational approaches has the potential to reap great rewards in the realization of these neglected works. The work of Roman Haubenstock- Ramati, and particularly his Decisions (1959–1961) for unspecified sound sources, serves as an example through analysis of its structure and a critical evaluation of performative possibilities. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE The Australian-American pianist Edward Neeman has won first prizes in the Rodrigo and Carlet international piano competitions and has performed with orchestras including the Prague Philharmonic, the Madrid Philharmonic, the Sydney Symphony, Melbourne Symphony, West Australia Symphony, Canberra Symphony, and The Queensland Orchestra. -

Weltmusik and the Globalization of New Music. In: the Modernist Legacy: Essays on New Music

Heile, B. (2009) Weltmusik and the globalization of new music. In: The Modernist Legacy: Essays on New Music. Ashgate, Farnham, UK, pp. 101- 121. ISBN 9780754662600 Copyright © 2009 Ashgate A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge The content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/55054/ Deposited on: 03 April 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 152 CHAPTER SIX Weltmusik and the Globalization of New Music Björn Heile In the Introduction to The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music the editors Nicholas Cook and the late Anthony Pople make the following claim: [The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music ] charts a transition between two quite different conceptions of ‘our’ music: on the one hand, the Western ‘art’ tradition that was accorded hegemonic status within an overly, or at least overtly, confident imperial culture centred on Europe at the turn of the twentieth century (a culture now distant enough to have become ‘their’ music rather than ‘ours’), and on the other hand, a global, post-colonial culture at the turn of the twenty-first, in which ‘world’ music from Africa, Asia, or South America is as much ‘our’ music as Beethoven, and in which Beethoven occupies as prominent a place in Japanese culture as in German, British, or American. -

Other Minds 13 Program

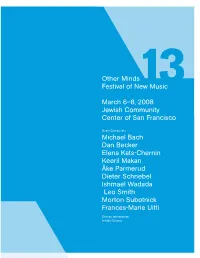

Other Minds Festival of New Music March 6–8, 2008 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Guest Composers Michael Bach Dan Becker Elena Kats-Chernin Keeril Makan Åke Parmerud Dieter Schnebel Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith Morton Subotnick Frances-Marie Uitti Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director 34 12 16 B 7 19 15 A 2 36 1 Other Minds, in association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the Eugene and Elinor Friend Center for the Arts at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, presents Other Minds 13 Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director Jewish Community Center of San Francisco March 6-7-8, 2008 Table of Contents 3 Message from the Artistic Director 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction 6 Concert 1 7 Concert 1 Program Notes 10 Concert 2 11 Concert 2 Program Notes 14 Concert 3 15 Concert 3 Program Notes 20 Other Minds 13 Composers 24 About Other Minds Other Minds 13 Festival Staff 25 Other Minds 13 Performers 28 Festival Supporters A Gathering of Other Minds Program Design by Leigh Okies. Layout and editing by Adam Fong. © 2008 Other Minds. All Rights Reserved. The Djerassi Resident Artists Program is a proud co-sponsor of Other Minds Festival XIII The mission of the Djerassi Resident Artists Program is to support and enhance the creativity of artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection, and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty, and to preserve the land upon which the Program is situated. The Djerassi Program annually welcomes the Other Minds Festival composers for a five-day residency for collegial interaction and preparation prior to their concert performances in San Francisco. -

Not Just a Pretty Voice: Cathy Berberian As Collaborator, Composer and Creator Kate Meehan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Not Just a Pretty Voice: Cathy Berberian as Collaborator, Composer and Creator Kate Meehan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Meehan, Kate, "Not Just a Pretty Voice: Cathy Berberian as Collaborator, Composer and Creator" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 239. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/239 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Bruce Durazzi Craig Monson Anca Parvulescu Dolores Pesce Julia Walker NOT JUST A PRETTY VOICE: CATHY BERBERIAN AS COLLABORATOR, COMPOSER AND CREATOR by Kate Meehan A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri copyright by Kate Meehan 2011 Abstract During her relatively brief career, Cathy Berberian (1925-83) became arguably the best- known singer of avant-garde vocal music in Europe and the United States. After 1950, when she married Italian composer Luciano Berio, Berberian premiered almost thirty new works by seventeen different composers and received the dedications of several more. Composers connected to her include: John Cage, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, Sylvano Bussotti, Henri Pousseur, Bruno Maderna, Bernard Rands, Roman Haubenstock- Ramati, and of course, Berio.