Power Play: Why NHL's Prohibition on Player Participation in Future Olympics Would Violate Sherman Antitrust Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penguins Their Fourth-Straight Win on Sunday Vs

PITTSBURGH AT BOSTON JANUARY 26, 2021 | 7:00 PM ET | TD GARDEN 100 GUENTZ-GOALS Jake Guentzel secured the Penguins their fourth-straight win on Sunday vs. NYR when he scored with 1:31 minutes left in the game. His goal marked his 100th in the NHL, in just his 249th career game. PIT n Guentzel is the 17th player, and 10th-fastest, to record his first 100 goals with Pittsburgh. AT n He also became the sixth member of the 2013 draft class, and only one outside of the top-10, to score 100 goals. BOS Fastest to 100 Goals 100-Goal Scorers Among 2013 NHL Draftees Penguins History Player Games Played Goals Draft Position ‘20-21 OVERALL 1. Mario Lemieux 159 Sean Monahan 545 196 #6 4-2-0 RECORD 3-1-1 2. Rob Brown 186 Nathan MacKinnon 531 192 #1 3. Pierre Larouche 187 Aleksander Barkov 481 155 #2 4-2-0 LAST 10 GAMES 3-1-1 4. Mike Bullard 206 Bo Horvat 453 125 #9 27.8% POWER-PLAY 35.3% 5. Evgeni Malkin 210 Elias Lindholm 529 122 #5 6. Kevin Stevens 216 Jake Guentzel 249 100 #77 76.2% PENALTY KILL 90.0% 7. Mark Recchi 218 n Guentzel’s 0.40 career goals-per-game ranks second among players from his 3.17 GF/GP 2.60 8. Sidney Crosby 219 2013 draft class, behind only Dominik Kubalik’s 0.43 G/GP. 3.83 GA/GP 2.00 9. Jaromir Jagr 245 n Since his NHL debut on Nov. 23, 2016, Guentzel’s 100 goals rank third on the Penguins and his 10 game-winning goals rank fifth (tied). -

Carolina Hurricanes

CAROLINA HURRICANES NEWS CLIPPINGS • April 7, 2021 With Petr Mrazek back, Hurricanes have goaltending decisions to make at trade deadline By Chip Alexander The goaltending question might be easier to answer if Mrazek had struggled a bit Sunday but he made 28 saves. For the Carolina Hurricanes, the sprint to the finish line of the He was strong when things were tight, in the final minutes of regular season has begun. regulation as the Stars pulled their goalie for a sixth attacker The Canes host the Florida Panthers on Tuesday and and attacked, hunting a tying goal. Thursday in what‘s presumably a preview of what should be “He didn’t have a lot of work for two (periods) and then when a Central Division first- or second-round playoff series. The we needed him, he was there in the last five minutes,” top four teams in each division qualify and the Panthers (26- Brind’Amour said. “He made three or more spectacular, 9-4) go into Tuesday’s game first in the division with 56 especially weird ones that got in that he couldn’t see. They points and the Canes (25-9-3) third with 53, one point behind weren’t Grade-A’s but they were coming from angles and Tampa Bay. screens. He fought through it. He was good, obviously.” The Panthers have played 39 games and the Canes 37, so If the Canes, with an eye to the playoffs, determine Mrazek the Canes’ two games-in-hand on Florida won’t change until will be their No. -

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 9 Craig Adams, Philippe Boucher, Matt Cooke, Sidney Crosby CAPTAIN, Pascal Dupuis, Mark Eaton, Ruslan Fedotenko, Marc-Andre Fleury, Mathieu Garon, Hal Gill, Eric Godard, Alex Goligoski, Sergei Gonchar, Bill Guerin, Tyler Kennedy, Chris Kunitz, Kris Letang, Evgeni Malkin, Brooks Orpik, Miroslav Satan, Rob Scuderi, Jordan Staal, Petr Sykora, Maxime Talbot, Mike Zigomanis Mario Lemieux CO-OWNER/CHAIRMAN Ray Shero GENERAL MANAGER, Dan Bylsma HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2009 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 116 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 93 GM PETER CHIARELLI, HC CLAUDE JULIEN v. GM/HC BOB GAINEY BRUINS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 16 1900 h et on CBC Saturday, April 18 2000 h et on CBC MONTREAL 2 @ BOSTON 4 MONTREAL 1 @ BOSTON 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BOSTON, Phil Kessel 1 (David Krejci, Chuck Kobasew) 13:11 1. BOSTON, Marc Savard 1 (Steve Montador, Phil Kessel) 9:59 PPG 2. BOSTON, David Krejci 1 (Michael Ryder, Milan Lucic) 14:41 2. BOSTON, Chuck Kobasew 1 (Mark Recchi, Patrice Bergeron) 15:12 3. -

Playing for Our Planet How Sports Win from Being Sustainable How Sports Sustainable from Being Win

with the support of PLaying for our planet for PLaying PLaying for our planet How sports win from being sustainable How sports win from being sustainable win being from sustainable sports How with contributions from: with the support of ABOUT THIS REPORT Environmental leadership is an increasingly important the development of a report which is designed to bring issue for all sport stakeholders and major sport events. together good practices by key stakeholders of the sport Environmentally conscious operations are no longer movement: from federations, teams, fans, sporting goods solely a focus of visionary thinking, but have become manufacturers and venue operators, to sponsoring partners, a vital operational and economic requirement for environmental organisations and policymakers. Its main federations, teams, rights holders, host cities, leisure objective is to highlight innovative solutions which enhance activities and partners linked to the sport movement. the environmental and sustainable performance of sports. UEFA, WWF and the Green Sports Alliance have led FOReWORD For quite some time sustainability was a foreign concept in the world of sport and just a decade ago it was still considered rather exotic by many in the industry. That is thankfully no longer the case today. This good practice report highlights the commitment made by many sports to environment and local communities. That means limiting our use of natural raise awareness of healthy and sustainable lifestyles and to take action against resources such as water, keeping the air clean, consuming less and more climate change. The activities showcased from around Europe show a great renewable energy, and recycling everything that can be given a new life. -

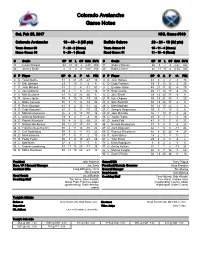

Colorado Avalanche Game Notes

Colorado Avalanche Game Notes Sat, Feb 25, 2017 NHL Game #910 Colorado Avalanche 16 - 40 - 3 (35 pts) Buffalo Sabres 26 - 24 - 10 (62 pts) Team Game: 60 7 - 20 - 2 (Home) Team Game: 61 15 - 11 - 4 (Home) Home Game: 30 9 - 20 - 1 (Road) Road Game: 31 11 - 13 - 6 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 31 Calvin Pickard 33 10 19 2 2.88 .909 31 Anders Nilsson 20 9 7 4 2.67 .922 40 Jeremy Smith 2 0 2 0 3.08 .912 40 Robin Lehner 42 17 17 6 2.54 .925 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 4 D Tyson Barrie 51 4 21 25 -27 14 4 D Josh Gorges 44 0 2 2 -3 33 6 D Erik Johnson 23 1 10 11 -2 4 6 D Cody Franson 53 3 13 16 -2 26 7 C John Mitchell 51 2 2 4 -11 41 9 L Evander Kane 48 21 11 32 -8 79 8 C Joe Colborne 49 4 1 5 -18 24 12 R Brian Gionta 60 12 15 27 -6 20 9 C Matt Duchene 54 16 20 36 -20 6 15 C Jack Eichel 39 13 20 33 -6 6 12 R Jarome Iginla 59 8 10 18 -19 54 21 R Kyle Okposo 59 18 21 39 -1 20 14 L Blake Comeau 55 7 5 12 -19 46 23 C Sam Reinhart 58 13 24 37 -2 8 17 R Rene Bourque 43 9 4 13 -13 42 26 L Matt Moulson 60 12 10 22 1 8 18 D Cody Goloubef 28 0 3 3 -10 25 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 53 6 7 13 -2 6 25 C Mikhail Grigorenko 56 6 12 18 -10 16 29 D Jake McCabe 55 1 10 11 4 24 27 L Andreas Martinsen 53 3 4 7 -8 32 38 D Taylor Fedun 25 0 7 7 3 16 28 D Patrick Wiercioch 50 4 8 12 -16 21 41 D Justin Falk 41 0 7 7 0 21 29 C Nathan MacKinnon 59 12 27 39 -18 10 44 L Nicolas Deslauriers 31 0 0 0 -6 23 32 D Francois Beauchemin 58 2 11 13 -10 22 47 D Zach Bogosian 34 1 5 6 -11 23 34 C Carl Soderberg 59 5 6 11 -13 20 55 D Rasmus Ristolainen 60 4 32 36 -4 25 45 D Mark Barberio 37 1 6 7 -2 10 56 R Justin Bailey 19 2 1 3 5 2 51 D Fedor Tyutin 50 1 9 10 -23 26 63 L Tyler Ennis 29 4 4 8 -4 2 83 L Matt Nieto 37 4 3 7 -7 6 71 L Evan Rodrigues 8 0 2 2 -1 0 92 L Gabriel Landeskog 49 11 12 23 -17 46 77 D Dmitry Kulikov 34 1 1 2 -13 24 96 R Mikko Rantanen 54 14 15 29 -23 12 82 L Marcus Foligno 60 9 7 16 -1 60 90 C Ryan O'Reilly 50 13 25 38 5 10 President Josh Kroenke Owner/CEO Terry Pegula Exec. -

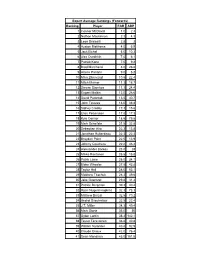

FHN 2021 Draft Guide

Expert Average Rankings (Forwards) Ranking Player EAR ADP 1 Connor McDavid 1.0 2.3 2 Nathan Mackinnon 2.3 4.3 3 Leon Draisaitl 2.8 3 4 Auston Matthews 4.0 6.9 5 Jack Eichel 5.0 10.3 6 Alex Ovechkin 7.0 6.1 7 Patrick Kane 7.0 9.8 8 Brad Marchand 8.0 26.6 9 Artemi Panarin 9.0 5.8 10 Mika Zibanejad 10.8 22.4 11 Mitch Marner 11.3 18.7 12 Steven Stamkos 11.3 24.4 13 Evgeni Malkin 13.0 28.6 14 David Pastrnak 13.5 40.7 15 John Tavares 16.0 33.8 16 Sidney Crosby 17.3 15.6 17 Elias Pettersson 17.8 17.3 18 Kyle Connor 18.5 75.6 19 Mark Scheifele 21.5 32.8 20 Sebastian Aho 22.3 13.8 21 Jonathan Huberdeau 22.3 22.3 22 Brayden Point 22.5 13.9 23 Johnny Gaudreau 22.8 48.2 24 Aleksander Barkov 23.8 28 25 Mikko Rantanen 25.5 15.8 26 Patrik Laine 26.0 34.1 27 Blake Wheeler 27.8 43.8 28 Taylor Hall 28.0 53.1 29 Matthew Tkachuk 28.3 39.6 30 Jake Guentzel 29.8 31.4 31 Patrice Bergeron 30.3 40.4 32 Ryan Nugent-Hopkins 32.3 73.3 33 Mathew Barzal 32.5 70.2 34 Andrei Svechnikov 33.5 22.4 35 J.T. Miller 34.3 49.4 36 Mark Stone 35.0 30 37 Dylan Larkin 38.3 142.1 38 Teuvo Teravainen 38.8 40.8 39 William Nylander 40.8 92.9 40 Claude Giroux 42.0 76.4 41 Sean Monahan 43.0 151.5 42 Max Pacioretty 43.3 46 43 Elias Lindholm 43.8 81.8 44 Filip Forsberg 46.0 77.1 45 Brock Boeser 47.0 51.7 46 Anze Kopitar 48.8 137 47 Travis Konecny 49.3 96.8 48 Sean Couturier 49.5 69.4 49 Kevin Fiala 51.8 82.5 50 Bo Horvat 52.3 141.4 51 Gabriel Landeskog 53.3 38.6 52 Brendan Gallagher 53.5 87.7 53 Evander Kane 54.8 90 54 Ryan O'Reilly 56.0 69.8 55 Anthony Mantha 56.3 153.7 56 Evgeny Dadonov -

Vancouver Canucks 2009 Playoff Guide

VANCOUVER CANUCKS 2009 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS VANCOUVER CANUCKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory . .3 Vancouver Canucks Playoff Schedule. 4 General Motors Place Media Information. 5 800 Griffiths Way CANUCKS EXECUTIVE Vancouver, British Columbia Chris Zimmerman, Victor de Bonis. 6 Canada V6B 6G1 Mike Gillis, Laurence Gilman, Tel: (604) 899-4600 Lorne Henning . .7 Stan Smyl, Dave Gagner, Ron Delorme. .8 Fax: (604) 899-4640 Website: www.canucks.com COACHING STAFF Media Relations Secured Site: Canucks.com/mediarelations Alain Vigneault, Rick Bowness. 9 Rink Dimensions. 200 Feet by 85 Feet Ryan Walter, Darryl Williams, Club Colours. Blue, White, and Green Ian Clark, Roger Takahashi. 10 Seating Capacity. 18,630 THE PLAYERS Minor League Affiliation. Manitoba Moose (AHL), Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL) Canucks Playoff Roster . 11 Radio Affiliation. .Team 1040 Steve Bernier. .12 Television Affiliation. .Rogers Sportsnet (channel 22) Kevin Bieksa. 14 Media Relations Hotline. (604) 899-4995 Alex Burrows . .16 Rob Davison. 18 Media Relations Fax. .(604) 899-4640 Pavol Demitra. .20 Ticket Info & Customer Service. .(604) 899-4625 Alexander Edler . .22 Automated Information Line . .(604) 899-4600 Jannik Hansen. .24 Darcy Hordichuk. 26 Ryan Johnson. .28 Ryan Kesler . .30 Jason LaBarbera . .32 Roberto Luongo . 34 Willie Mitchell. 36 Shane O’Brien. .38 Mattias Ohlund. .40 Taylor Pyatt. .42 Mason Raymond. 44 Rick Rypien . .46 Sami Salo. .48 Daniel Sedin. 50 Henrik Sedin. 52 Mats Sundin. 54 Ossi Vaananen. 56 Kyle Wellwood. .58 PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM. .60 CANUCKS SEASON IN REVIEW 2008.09 Final Team Scoring. .64 2008.09 Injury/Transactions. .65 2008.09 Game Notes. 66 2008.09 Schedule & Results. -

Storm May Bring Snow to Valley Floor

Mendo women Rotarians plan ON THE MARKET fall to Solano Super Bowl bash Guide to local real estate .............Page A-6 ............Page A-3 ......................................Inside INSIDE Mendocino County’s Obituaries The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Rain High 45º Low 41º 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY Jan. 25, 2008 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 38 pages, Volume 149 Number 251 email: [email protected] Storm may bring snow to valley floor By ZACK SAMPSEL but with low pressure systems from and BEN BROWN Local agriculture not expected to sustain damage the Gulf of Alaska moving in one The Daily Journal after another the cycle remains the A second round of winter storms the valley floor, but the weather is not the county will experience scattered ing routine for some Mendocino same each day. lining up to hit Mendocino County expected to be a threat to agriculture. showers today with more mountain County residents. The previous low pressure system today is expected to bring more rain, According to reports from the snow to the north in higher eleva- Slight afternoon warmups have cold temperatures and snow as low as National Weather Service, most of tions, which has been the early-morn- helped to make midday travel easier, See STORM, Page A-12 GRACE HUDSON MUSEUM READIES NEW EXHIBIT Kucinich’s wife cancels planned stop in Hopland By ROB BURGESS The Daily Journal Hey, guess what? Kucinich quits Elizabeth Kucinich is coming to Mendocino campaign for County. Wait. Hold on. No, White House actually she isn’t. Associated In what should be a Press familiar tale to perennial- Democrat ly disappointed support- Dennis Kuci- ers of Democratic presi- nich is aban- dential aspirant Rep. -

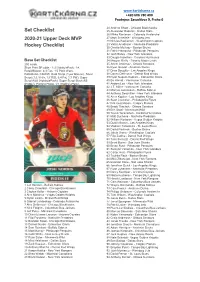

Set Checklist 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP Hockey Checklist

www.kartickarna.cz +420 606 780 400 Prodejna: Zavadilova 9, Praha 6 24 Andrew Shaw - Chicago Blackhawks Set Checklist 25 Alexander Radulov - Dallas Stars 26 Mikko Rantanen - Colorado Avalanche 27 Mark Scheifele - Winnipeg Jets 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP 28 Nicklas Backstrom - Washington Capitals Hockey Checklist 29 Viktor Arvidsson - Nashville Predators 30 Charlie McAvoy - Boston Bruins 31 Patric Hornqvist - Pittsburgh Penguins 32 Josh Bailey - New York Islanders 33 Dougie Hamilton - Carolina Hurricanes Base Set Checklist 34 Morgan Rielly - Toronto Maple Leafs 250 cards. 35 Artem Anisimov - Ottawa Senators Short Print SP odds - 1:2 Hobby/ePack; 1:4 36 Ryan Getzlaf - Anaheim Ducks Retail/Blaster; 4:3 Fat;, 1:5 Pack Wars. 37 Drew Doughty - Los Angeles Kings PARALLEL CARDS: Gold Script (1 per Blaster), Silver 38 Danny DeKeyser - Detroit Red Wings Script (1:3.3 H/e, 1:7 R/B, 3:4 Fat, 1:7 PW), Super 39 Ryan Nugent-Hopkins - Edmonton Oilers Script #/25 (Hobby/ePack), Super Script Black #/5 40 Bo Horvat - Vancouver Canucks (Hobby), Printing Plates 1/1 (Hobby/ePack). 41 Anders Lee - New York Islanders 42 J.T. Miller - Vancouver Canucks 43 Marcus Johansson - Buffalo Sabres 44 Anthony Beauvillier - New York Islanders 45 Anze Kopitar - Los Angeles Kings 46 Sean Couturier - Philadelphia Flyers 47 Erik Gustafsson - Calgary Flames 48 Brady Tkachuk - Ottawa Senators 49 Eric Staal - Minnesota Wild 50 Teuvo Teravainen - Carolina Hurricanes 51 Matt Duchene - Nashville Predators 52 William Karlsson - Vegas Golden Knights 53 Dustin Brown - Los Angeles Kings -

Dobber's 2010-11 Fantasy Guide

DOBBER’S 2010-11 FANTASY GUIDE DOBBERHOCKEY.COM – HOME OF THE TOP 300 FANTASY PLAYERS I think we’re at the point in the fantasy hockey universe where DobberHockey.com is either known in a fantasy league, or the GM’s are sleeping. Besides my column in The Hockey News’ Ultimate Pool Guide, and my contributions to this year’s Score Forecaster (fifth year doing each), I put an ad in McKeen’s. That covers the big three hockey pool magazines and you should have at least one of them as part of your draft prep. The other thing you need, of course, is this Guide right here. It is not only updated throughout the summer, but I also make sure that the features/tidbits found in here are unique. I know what’s in the print mags and I have always tried to set this Guide apart from them. Once again, this is an automatic download – just pick it up in your downloads section. Look for one or two updates in August, then one or two updates between September 1st and 14th. After that, when training camp is in full swing, I will be updating every two or three days right into October. Make sure you download the latest prior to heading into your draft (and don’t ask me on one day if I’ll be updating the next day – I get so many of those that I am unable to answer them all, just download as late as you can). Any updates beyond this original release will be in bold blue. -

Florida Panthers Game Notes

Florida Panthers Game Notes Sat, Oct 5, 2019 NHL Game #21 Florida Panthers 0 - 1 - 0 (0 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 1 - 0 - 0 (2 pts) Team Game: 2 0 - 0 - 0 (Home) Team Game: 2 1 - 0 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 1 0 - 1 - 0 (Road) Road Game: 1 0 - 0 - 0 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 33 Sam Montembeault - - - - - - 35 Curtis McElhinney - - - - - - 72 Sergei Bobrovsky 1 0 1 0 4.07 .862 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 1 1 0 0 2.03 .946 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Josh Brown 1 0 0 0 0 0 7 R Mathieu Joseph 1 0 1 1 0 0 3 D Keith Yandle 1 0 0 0 -1 0 9 C Tyler Johnson 1 0 0 0 0 0 5 D Aaron Ekblad 1 0 1 1 -2 0 14 L Pat Maroon 1 1 0 1 0 0 6 D Anton Stralman 1 0 0 0 1 0 17 L Alex Killorn 1 0 2 2 2 0 7 C Colton Sceviour 1 0 0 0 -1 0 18 L Ondrej Palat 1 1 0 1 2 0 8 C Jayce Hawryluk - - - - - - 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 1 1 0 1 0 0 10 R Brett Connolly 1 0 1 1 0 0 23 C Carter Verhaeghe 1 0 0 0 1 0 11 L Jonathan Huberdeau 1 0 0 0 -2 2 27 D Ryan McDonagh 1 0 0 0 1 0 13 D Mark Pysyk - - - - - - 28 R Luke Witkowski 1 0 0 0 0 0 16 C Aleksander Barkov 1 0 0 0 0 0 37 C Yanni Gourde 1 0 0 0 0 0 19 D Mike Matheson 1 0 0 0 -1 0 44 D Jan Rutta - - - - - - 21 C Vincent Trocheck 1 1 1 2 0 0 46 C Gemel Smith 1 0 0 0 0 2 52 D MacKenzie Weegar 1 0 0 0 0 0 55 D Braydon Coburn 1 0 0 0 1 0 55 C Noel Acciari 1 0 0 0 -1 0 71 C Anthony Cirelli 1 0 1 1 1 0 62 C Denis Malgin 1 0 0 0 0 0 77 D Victor Hedman 1 0 1 1 -1 2 63 R Evgenii Dadonov 1 0 0 0 -1 0 81 D Erik Cernak 1 1 0 1 1 0 68 L Mike Hoffman 1 1 0 1 -1 2 86 R Nikita Kucherov 1 1 1 2 1 0 73 L Dryden Hunt 1 0 0 0 0 0 91 C Steven Stamkos 1 0 0 0 0 0 77 C Frank Vatrano 1 0 0 0 -2 2 98 D Mikhail Sergachev 1 0 3 3 2 4 95 C Henrik Borgstrom 1 0 0 0 -1 0 President of Hockey Operations & Dale Tallon Vice President & General Manager, Julien BriseBois General Manager Alternate Governor Sr. -

Backstrom1,000 Nhl Games

NICKLAS BACKSTROM1,000 NHL GAMES ND 2 PLAYER IN FRANCHISE HISTORY TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH THE CAPITALS TH 14 ACTIVE PLAYER TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH ONE FRANCHISE TH 69 PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH ONE FRANCHISE TH 36 ACTIVE PLAYER TO REACH 1,000 GAMES PLAYERS WHO HAD 700+ CAREER ASSISTS BY THEIR MILESTONE GAMES 1,000TH GAME RD PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY 353 OCT. 5, 2007 @ WAYNE GRETZKY 1516 TO REACH 1,000 GAMES 1 PHILIPS ARENA PAUL COFFEY 910 TH NOV. 19, 2008 ADAM OATES 860 @ 14 SWEDISH-BORN PLAYER HONDA CENTER IN NHL HISTORY TO REACH 100 BRYAN TROTTIER 817 1,000 GAMES SIDNEY CROSBY 810 DEC. 19, 2009 @ 200 REXALL PLACE DALE HAWERCHUK 795 RD 23 PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY WITH 700+ MARCEL DIONNE 794 ASSISTS BY THEIR 1,000TH GAME FEB. 6, 2011 VS. 21 of the 23 players to accomplish VERIZON CENTER STEVE YZERMAN 790 this feat are in the Hockey Hall of 300 Fame, while two are not yet eligible DENIS SAVARD 789 (Sidney Crosby, Jaromir Jagr) MARCH 31, 2013 @ RON FRANCIS 780 400 WELLS FARGO CENTER ND RAY BOURQUE 778 2 ACTIVE PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY WITH 700+ ASSISTS BY THEIR MARK MESSIER 778 OCT. 18, 2014 1,000TH GAME (SIDNEY CROSBY) 500 VS. VERIZON CENTER JOE SAKIC 765 BERNIE FEDERKO 761 DEC. 8, 2015 592-296-111 600 VS. VERIZON CENTER JAROMIR JAGR 760 1,295 POINTS WITH BACKSTROM IN THE LINEUP BOBBY CLARKE 754 JAN. 24, 2017 @ 700 CANADIAN TIRE CENTRE GUY LAFLEUR 747 11TH 4TH PHIL ESPOSITO 737 PLAYER IN FRANCHISE PLAYER FROM THE MARCH 8, 2018 HISTORY TO PLAY THEIR 2006 NHL DRAFT @ STAPLES CENTER JARI KURRI 721 1,000TH CAREER GAME CLASS TO REACH THE 800 WITH THE CAPITALS 1,000-GAME MARK DENIS POTVIN 718 OCT.