Between Holiness and Propaganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

State of Conservation of Properties Inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger

World Heritage 39 COM WHC-15/39.COM/7A.Add Paris, 29 May 2015 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-ninth session Bonn, Germany 28 June – 8 July 2015 Item 7A of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of the properties inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger SUMMARY In accordance with Section IV B, paragraphs 190-191 of the Operational Guidelines, the Committee shall review annually the state of conservation of properties inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger. This review shall include such monitoring procedures and expert missions as might be determined necessary by the Committee. This document contains information on the state of conservation of properties inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The World Heritage Committee is requested to review the reports on the state of conservation of properties contained in this document. The full reports of Reactive Monitoring missions requested by the World Heritage Committee are available at the following Web address in their original language: http://whc.unesco.org/en/sessions/39COM/documents All state of conservation reports are also available through the World Heritage State of conservation Information System at the following Web address: http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc Decision required: The Committee is requested to review the following state of conservation reports. The Committee may wish to adopt the draft Decision presented at the end of each state of conservation report. TABLE OF CONTENT NATURAL PROPERTIES ...................................................................................................................... -

Archaeological Activities in Politically Sensitive Areas in Jerusalem's Historic Basin

Archaeological Activities in Politically Sensitive Areas in Jerusalem's Historic Basin 2015 >> Preface >> Excavations in the Old City >> The Old City Walls >> The Nea Church >> Herod’s Gate/Burj al-Laklak >> Ha-Gai/Al-Wad Street >> Damascus Gate >> Jaffa Gate >> Hezekiah’s Pool >> Ophel Excavations - Davidson Center >> Bab al-Rahma Cemetery >> Beit ha-Liba >> The Mughrabi Bridge >> The Western Wall Plaza >> The Little Western Wall >> Other Projects in the Western Wall Plaza >> Excavations in Silwan >> The Givati Parking Lot >> Jeremiah’s Well >> The Spring House >> The Tel Aviv University Excavations in Silwan >> Summary Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. November 2014 Preface Excavations in the Old City Jerusalem's Old City and the Historic Basic (also called the Holy Basin) contain some of the most The Old City Walls important sites to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. On account of its religious and historical In 2004 a number of stones fell from the walls of the Old City into the courtyard of the College significance, the city has attracted the attention of many scholars: already in the 19th century des Frères school in the Christian Quarter. This incident led the authorities responsible for the various scholars were conducting scientific excavations in the Old City. The scope of archaeolog- Old City and its antiquities to preserve and reinforce the walls. -

ISRAEL NEWS in Northern Gaza

בס״ד Hamas' military wing עש״ק פרשת דברים 8 Av 5776 ISRAEL NEWS in northern Gaza. He August 12, 2016 prioritized Issue number 1113 A collection of the week’s news from Israel rehabilitation efforts in areas where From the Bet El Twinning / Israel Action Committee of members of Hamas reside. When Jerusalem 6:46 tunnel openings were detected in Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto Congregation Toronto 8:07 homes that were renovated by the UNDP, Hamas would take control of the site, and contrary to U.N. regulations, the UNDP would refrain Commentary… from reporting the incidents to the United Nations Mine Action Service. In his interrogation, Burash revealed a list of Hamas operatives Israel’s Bloodthirsty ‘Partner’ embedded in other aid organizations in Gaza. By NY Post Post Editorial Board Anyone who thought Hamas would honor its agreements rather than Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’ party Fatah had an important exploit these humanitarian aid groups, whose aim is to help the suffering boast to share on its Facebook page last week: It has “killed 11,000 civilian population in Gaza, was mistaken. This is because Hamas does Israelis.” not care for the population it governs, as those who sought to help the Mind you, these are the Palestinian “moderates” who the world expects needy expected. Quite the opposite: Hamas sees the civilian population Israel to treat as a “partner for peace.” under its boot as just another resource to use in its war against Israel, and Translated from Arabic, the post reads: “For the argumentative . the does not bat an eyelash when over half a humanitarian organization's ignorant . -

Hoffman V. Director General of the Prime Minister's Office

HCJ 3358/95 Petitioners: 1. Anat Hoffman 2. Chaya Beckerman 3. International Committee for Women of the Wall, Inc. by Miriam Benson v. Respondents: 1. Director General of the Prime Minister’s Office 2. Director General of the Ministry of Religion 3. Director General of the Ministry of the Interior 4. Director General of the Ministry of Police 5. Legal Advisor to the Prime Minister’s Office 6. Prime Minister’s Advisor on the Status of Women 7. Government of Israel Attorneys for the Petitioners: Jonathan Misheiker, Adv., Francis Raday, Adv. Attorney for the Respondents: Uzi Fogelman, Adv. The Supreme Court as High Court of Justice [17 Iyar 5760 (May 22, 2000)] Before Justice E. Mazza, Justice T. Strasberg-Cohen, Justice D. Beinisch Objection to an Order Nisi This petition concerns the Petitioners’ request to establish arrangements that would enable them to pray in the prayer area adjacent to the Western Wall in “women’s prayer groups, together with other Jewish women, while they are wearing tallitot [prayer shawls] and reading aloud from the Torah”, as required by the judgment of the Supreme Court in HCJ 257/89 Hoffman v. Director of the Western Wall (hereinafter: the First Judgment). Pursuant to the First Judgment, the Government decided, in 1994, to appoint a Directors General Committee, headed by the Director General of the Prime Minister’s Office, to present a proposal for a possible solution that would ensure the Petitioners’ right of access and worship in the Western Wall Plaza, while limiting the affront to the feelings of other worshippers at the site. -

PDF (Volume 1)

Durham E-Theses The old city of Jerusalem: aspects op the development op a religious centre Hopkins, W. J. How to cite: Hopkins, W. J. (1969) The old city of Jerusalem: aspects op the development op a religious centre, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8763/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Summary It is generally recognised that the Old City of Jerusalem is first and foremost a religious centre of great importance in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Yet the exact nature of the impact of roHgi nn on± the geography of the city is not so clearly known. The way in which religion through the pilgrim trade has over the centuries permeated into the general economy of the city would suggest that the influence of this factor is large. -

Jerusalem Israeli Settlement Activities & Related Policies

October 2011 3rd revised, updated edition revised, 3rd JERUSALEM Israeli Settlement Activities & Related Policies INTRODUCTION While the focus of this bulletin is on settlement-related topics, it should be noted that Israel’s ongoing efforts at circumventing Since the start of the occupation in 1967, all Israeli governments diplomacy are further aided by its discriminatory system of resi- have zealously pursued a policy to transform the city’s Arab char- dency rights and housing policies, its closure and permit regime, acter and ‘Judaize’ East Jerusalem to create a new geopolitical re- as well as ongoing house demolitions and the construction of the ality that guarantees Israeli territorial, demographic, and religious separation barrier. control over the entire city. In violation of international law (espe- cially regarding the transfer of civilians in occupied territory), Is- rael has expropriated huge areas of occupied East Jerusalem land FACTS AT A GLANCE and built numerous settlements, while simultaneously depriving Palestinian residents of building, housing, and infrastructure re- • Only 13% (or 9.18 km2) of the annexed municipal area is cur- quirements. rently zoned for Palestinian construction. • In contrast, 35% (24.5 km2) are expropriated for settlements, Although the issue of Jerusalem has always been at the heart of 22% (15.48 km2) are zoned for “green areas” and public infra- the Arab-Israeli conflict, negotiations over its status were post- structure, and 20% (21.35 km2) as “unplanned areas” (B’Tselem, poned during the Oslo -

Tightening the Ring of Israeli Settlement Around the Old City of Jerusalem Map Notes

Tightening the Ring of Israeli Settlement around the Old City of Jerusalem Map Notes December 2018* Numbers below are pegged to numbers on accompanying map. Sheikh Jarrah 1 & 2 Plans for the Ohr Somayach Yeshiva (also, “Glassman Yeshiva”) and a privately promoted office building – Two Israeli plans for buildings to be constructed on a lot of roughly 5 dunams on the southwest edge of the neighborhood, next to the Green Line, on the Palestinian side. The plan for the Ohr Somayach Yeshiva (Plan No. 68858) calls for construction of an eleven-story building with eight levels above ground and three below, including a dormitory for hundreds of students and housing for faculty. The plan was submitted by the Ohr Somayach Institutions, to which the Israel Land Authority has already allotted land without a transparent tender process, and approved for deposit by the District Planning and Building Committee in July 2017. In the master plan for the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood, the lot is designated for public buildings to serve neighborhood residents. The plan for the six-story office building (Plan No. 499699), submitted by private Israeli entrepreneurs, was deposited in April 2018, and in August 2018, the Local Planning and Building Committee recommended it for approval by the District Committee. The plan was approved in December 2018. 3 & 5 Plans for new construction in Um Haroun (Sheikh Jarrah) necessitating the eviction of Palestinian families – Two plans for new residential buildings that will necessitate the demolition of existing Palestinian homes: Plan No. 14151 for construction of a three-story building with three residential units and Plan No. -

Weeping Walls Free

FREE WEEPING WALLS PDF Gerri Hill | 264 pages | 22 Jan 2014 | BELLA BOOKS | 9781594933868 | English | Ferndale, MI, United States Weeping Walls - A Popular Water Feature | Platinum Pools Log in to get trip updates and message other travelers. Weeping Wall 2 Reviews. Geologic Formations. Sorry, there are no tours or activities available to book online for the date s you selected. Please choose a different date. Quick View. Scenic Snow Cat Experience. More Info. Abraham Lake Ice Walk. Horseback Riding in Lacombe, Alberta. Full view. Banff National Park, Alberta Canada. Best nearby. Get Weeping Walls know the area. Exploring Jasper National Park on your own can mean lots of driving, but you are free to enjoy the view on this scenic tour of Maligne Valley, Medicine Lake, and Maligne Lake. Frequent stops for short Weeping Walls ensure plenty of time Weeping Walls stretch your legs, and you have the choice between a guided hike at Maligne Lake or Weeping Walls boat cruise to Spirit Island. More info. Weeping Walls a review. Traveler rating. Selected filters. All reviews falls. Toronto, Canada contributions 24 helpful votes. Cool to see. Simple roadside stop to see the water falls come down sheer cliffs in multiple spots. Great for a Weeping Walls. Read more. Date of experience: June Begonia33 wrote a review Oct Fountain Hills contributions 77 helpful votes. Wall of waterfalls. This is a long cliff with numerous waterfalls. The cliff height is higher that feet. This is beautiful display of falls. Worth a stop. Date of experience: Weeping Walls Helpful Share. Share your best travel photo. -

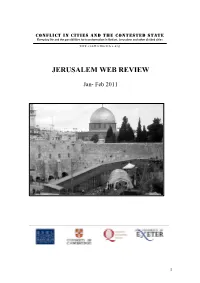

Jerusalem Web Review

CONFLICT IN CITIES AND THE CONTESTED STATE Everyday life and the possibilities for transformation in Belfast, Jerusalem and other divided cities www.conflictincities.org JERUSALEM WEB REVIEW Jan- Feb 2011 1 Jerusalem Web Review (Jan –Feb 2011) Contents The Palestinian Papers (Al-Jazeera files) 1. The Palestine Papers: "The biggest Yerushalayim" 2. Netanyahu secretly promised not to link Jerusalem and nearby settlement, Palestine papers show 3. Sparking Outrage, Political Storm 4. Al-Jazeera angers Palestinians 5. The Palestine Papers: Al-Jazeera Has an Agenda International responses to Jerusalem and the peace-process 6. EU Heads Recommendations on Jerusalem 7. US veto underscores failure of US-sponsored 'peace process' Deconstructing and reconstructing East Jerusalem 8. Toward a point of no return: Lifting the political restraints in East Jerusalem 9. The 10 plagues of east Jerusalem 10. Applied Research Institute Jerusalem (ARIJ) Report on Israeli Colonization activities in Jerusalem, Vol. 150, January 2011 11. Court orders government to accommodate East Jerusalem school children 12. Netanyahu commits to promoting Arab construction in East Jerusalem 13. Army colleges to move to east Jerusalem 14. Over 100 Participants Mark Two Year Anniversary to Solidarity Tent in East Jerusalem’s Silwan 15. Families forced out as army occupies Jerusalem rooftop Jerusalem’s Grey zones 16. No man's land in east Jerusalem: Chaos reigns supreme 17. Shin Bet warns of increased PA security involvement in East Jerusalem 18. Jerusalem MPs hold Palestinian Authority complicit in the Judaization of the Holy City Excavating and disputing sacred space 19. Digging completed on tunnel under Old City walls in East Jerusalem 20. -

Possessing History

2016 Possessing History: Contextualizing the Use of Narrative History in Moroccan-Jewish Studies A DIVISION THREE BY: THEODORE SAUL MILLER Under the Advisory Guidance of: Figure 1: A photograph hanging on the wall of the Office Aaron Berman (Co-Chair) Rachel Ama Asaa Engmann (Member) Rachel Rubinstein (Co-Chair) Cover Images, left to right: A photograph from Edmond Gabai’s collection of items left behind by Moroccan Jews leaving in Fes in between 1948-76 (taken by Author, 2016); and a photograph from a Mimouna Celebration in Casablanca in the 1950s (Dafina Archives) Table of Contents: Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Introducing Jewish Moroccan Heritage Section 1.1: Introduction Pages 9-7 Section 1.2: Understanding History and Heritage Pages 10-17 Section 1.3: Framing the Dispute over Moroccan Jewish Heritage Pages 17-27 Section 1.4: Positionality and Methodology Pages 27-35 Chapter 2: Disputed Narratives of the “Historic” Maghreb Section 2.1: Pre-Islamic Morocco (Before 750 CE) Pages 36-43 Section 2:2: The Early Islamic Monarchs (750-1000 CE) Pages 43-51 Section 2.3: The First “Moroccan” Empires (1000-1250 CE) Pages 51-59 Section 2.4: The Marinids and the Mellah (1250-1500 CE) Pages 59-67 Section 2.5: Sharifian Morocco (1500-1800 CE) Pages 67-73 Chapter 3: Narratives of Colonialism, Nationalism, and Oppression Section 3.1: The Nineteenth Century Pages 93-79 Section 3.2: The French Protectorate Era (1912-1925) Pages 79-85 1 |Possessing History Table of Contents (cont.) Section 3.3: Moroccan Nationalism and Judaism (1925-1948) Pages 85-91 Section 3.4: Independence, Zionism, and Emigration. -

Topography of Jerusalem.'

444 Topography of Jerwaiem. [APRIL, ARTICLE IX. TOPOGRAPHY OF JERUSALEM.' BY JOBBPH P. TROKPSON, D. D., NEW YORK.. WHEN Josephus wrote the fifth book of his Jewish War, he intended to give so accurate a description of the site and the structure of Jerusalem, that one familiar with the city should be able to reconstruct it in imagination; and, that the stranger should also be able to construct it upon a map, and to trace the siege of Titus, from wall to wall and tower to tower, as a spectator might have done from the summit of the mount of Olives. But in sketching the battle-ground of the Roman general, the Jewish historian only projected a battle-ground for futwe topographers; and squadrons of Rabbinists, traditionists, archmologists, geographers, explo rers, engineers, and draughtsmen, sciolists and scholars, English, German, American, have deployed about the city, from Hippicus to Antonia, assaulting chiefly the second wall of their antagonists, and waging the fiercest contlict over the Tyropreon valley. Within the last twenty years, espe cially, the topography of Jerusalem has become a subject not only of renewed investigation, but of elaborate and even acrimonious controversy •• Travellers, by no means versed in archmology, and with no previous thought of historical investigations, are incited by the view of unquestionable remains of the Jewish and the Roman periods of the city, to put forth descriptions and theories of its ancient structure with all the assurance and profundity of antiquarian re search; and thus the public mind is perplexed and divided according to the seeming competence and authority of the witnesses.