Possessing History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Catherine Manhardt BA: International Studies Honors Capstone: General University Honors Spring 2011 Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus

1 Catherine Manhardt BA: International Studies Honors Capstone: General University Honors Spring 2011 Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Powerful Beliefs: the role religion in constructing political legitimacy in Morocco Introduction: Enter any store, step into any cafe, or turn on any state-sponsored television channel in Morocco and chances are one will be greeted by the visage of Morocco's young monarch, King Muhammed VI. In some of these photos, the King will cut a dapper figure in an impeccably tailored western suit and clean-shaven face. In others, he will be sporting a serious five o'clock shadow and dressed in a traditional white djellaba, yellow slippers, and a red fez. Superficial as it may seem, in this case the clothes really do say a great deal about the man, and on a more fundamental level, the nature Morocco's political system. "The King, "Amir Al-Muminin"(Commander of the Faithful), shall be the Supreme Representative of the Nation and the Symbol of the unity thereof. He shall be the guarantor of the perpetuation and the continuity of the State 1." These two sentences mark the beginning of Article 19 in Morocco's 1996 Constitution and serve as the introduction to sixteen articles outlining the place of the monarchy in Morocco's political system. This important article, with its dual declaration of the monarch as both King and Commander of the Faithful, makes the clear point that legitimacy in the Moroccan context contains both religious and political dimensions even in this 21st century. This paper seeks to explore the deep link between religious and political legitimacy within the Moroccan monarchy. -

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco 2018 Final

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco March 15-28, 2018 (arriving from Spain and Portugal) PT 1 Charles Landelle-“Juive de Tanger” Unlike our astronauts who travel to "outer space," going to Morocco is a journey into "inner space." For Morocco reveals under every tree and shrub a spiritual reality that is unlike anything we have experienced before, particularly as Jewish travelers. We enter an Islamic world that we have been conditioned to expect as hostile. Instead we find a warmth and welcome that both captivates and inspires. We immediately feel at home and respected as we enter a unique multi-cultural society whose own 2011 constitution states: "Its unity...is built on the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Amazigh and Saharan-Hassani components, is nurtured and enriched by African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean constituents." A journey with KIVUNIM through Morocco is to glimpse the possibilities of the future, of a different future. At our alumni conference in December, 2015, King Mohammed VI of Morocco honored us with the following historic and challenge-containing words: “…these (KIVUNIM) students, who are members of the American Jewish community, will be different people in their community tomorrow. Not just different, but also valuable, because they have made the effort to see the world in a different light, to better understand our intertwined and unified traditions, paving the way for a different future, for a new, shared destiny full of the promises of history, which, as they have realized in Morocco, is far from being relegated to the past.” The following words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel remind us of the purpose of our travels this year. -

Ne-Yo Au Festival Mawazine

Communiqué de presse Rabat, 23 avril 2014 La dernière découverte du rap US à Mawazine Ne-Yo se produira en concert à Rabat le 04 juin 2014 L’Association Maroc Cultures a le plaisir de vous annoncer la venue du chanteur américain Ne-Yo à l’occasion de la 13ème édition du Festival - Mawazine Rythmes du Monde. Ne-Yo se produira mercredi 04 juin 2014 sur la scène de l’OLM-Souissi à Rabat. Dernière découverte du prestigieux label Def Jam, dont l’histoire se confond en grande partie avec celle du rap américain, Ne-Yo (né Shaffer Smith) a hérité d’une voix unique en son genre, inspirée de Stevie Wonder et des plus grands noms de la soul. L’artiste a obtenu en 2008 le Grammy Award du meilleur album contemporain R&B et composé des tubes pour Beyoncé, Rihanna et Britney Spears. Né en 1979 à Los Angeles, Ne-Yo est élevé par une famille de musiciens et se passionne très tôt pour la musique. Ses idoles de l'époque s’appellent Whitney Houston et Michael Jackson. Au cours de cette période, le garçon développe une culture musicale importante, s’essaie au chant, à la composition et à l'écriture. Après plusieurs prestations réussies, Ne-Yo retient l'attention de Def Jam, le label le plus actif de la scène R&B. Avec lui, le chanteur enregistre les singles So Sick , Sexy Love et When You're Mad , qui reçoivent un accueil très favorable dans les clubs de la côte ouest. Ne-Yo sort en 2006 son premier album, In My Own Words , qui se vend à 1 million d’exemplaires. -

Sherith Israel

the Jewish bserver www.jewishobservernashville.org Vol. 82 No. 10 • October 2017 11 Tishrei-11 Cheshvan 5778 Holocaust With ‘Violins of Hope,’ community Memorial, examines Holocaust, social issues art events By KATHY CARLSON intage musical instru- ments that were lovingly on Oct. 8 restored after surviving or more than 10 years, the Holocaust will give Nashville has had a site ded- all of Nashville a focus for icated to remembering those better understanding how who lost their lives through Vpeople confront injustice and hatred. the institutionalized evil The instruments – collectively called of the Holocaust. On Oct. the Violins of Hope – will be played F8, the Jewish community will gather by Nashville Symphony musicians and at the Nashville Holocaust memorial exhibited at the Nashville Library next on the grounds of the Gordon Jewish spring as the city’s Jewish, arts and com- Community Center to remember those munity organizations come together with who were killed as well as Holocaust a host of related programs. survivors, including those who made the Mark Freedman, executive director Nashville memorial possible. of the Jewish Federation and Foundation “So much has changed over the of Nashville and Middle Tennessee, years since the Memorial was complet- spoke at a news conference detailing ed,” said Felicia Anchor, who helped upcoming programs. He thanked the organize the memorial. The community many partner organizations and individu- has lost several survivors who were als who have worked to bring the Violins instrumental in establishing the memo- of Hope to Nashville. rial, including Elizabeth Limor and He recalled how he visited Yad At a news conference at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center, Mark Freedman, Esther Loeb. -

Timeline / 500 to 1300 / MOROCCO

Timeline / 500 to 1300 / MOROCCO Date Country | Description 533 A.D. Morocco The Vandals take refuge in Mauritania Tingitana (Northern Morocco in Antiquity). 544 A.D. Morocco The Goths attempt to occupy the town of Sebta. 578 A.D. Morocco Byzantium puts down the Berber revolt that flared up after local chieftains are murdered by Sergius, Byzantine Governor of Tripoli. 681 A.D. Morocco ‘Uqba (Okba) ibn Nafi reaches Sebta, Tangiers then Walili (Ancient Volubilis) before going on to the town of Nfis in the Haouz and Igli in the Souss. 711 A.D. Morocco Tarik ibn Ziyad crosses the Straits of Gibraltar, defeats King Roderick of Spain and takes Córdoba and Toledo. 740 A.D. Morocco Northern Morocco is shaken by the Kharijite revolt lead by Maysara al-Matghari. 757 A.D. Morocco Issa ibn Yazid al-Assouad founds the town of Sijilmassa at Tafilalet, the great desert port on the gold route. 788 A.D. Morocco Idris ibn ‘Abdallah (Idris I) takes up residence at Walili, then in the Andalusian Quarter (Adwat al-Andalousiyyin) in Fez, which he founded on the right bank of the Wadi Fez. 808 A.D. Morocco Idris II (son of Idris I) founds the town of al-Aliya in the Kairouan Quarter (Adwat al- Qayrawaniyyin) on the left bank of the Wadi Fez. 836 A.D. Morocco A moribund Idrisid Morocco vacillates between the Umayyads of al-Andalus and the Fatimids of Ifriqiya for 27 years. 857 A.D. Morocco Date Country | Description Fatima al-Fihriya, daughter of a Kairouanese man living in Morocco, founds the Qarawiyin Mosque in Fez. -

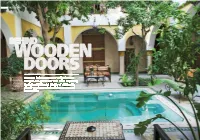

The Art of Decadence Dar Doukkala

The Art of Decadence Dar Doukkala he arched wooden doorway that leads you into Dar Doukkala from Tthe busy street of the same name is pleasing, but no-more so than many of the houses in Marrakech Medina, although the stately sweep of the stairway just inside is pretty spiffy, with its white and red tiled treads and vaguely sensual hooping rise of the chrome banister. The internal garden is delightful, with pathways separating the quadrants of palm trees and lush floribunda, but other than the size and the pretty alcoves set in the walls to sit and mull the day away in, it’s akin to what you would expect to find as the centerpiece of many of the best riads. But it’s when you get to the bedrooms that the ‘Oh my giddy aunt!’ effect kicks in, backed up later when you take yourself down to dinner in the long, chi-chi dining room that’s just made for romantic evenings and whispered conversations. It doesn’t take long to realise that this is no ordinary riad, and certainly no ordinary restoration. Many of even the best riads in the ancient quarter have the reputation for bedrooms being a bit pokey, but Dar Doukkala was obviously designed as the riad keeping the hubbub of the Medina streets a grand residence of someone of substance in the at bay. early 19th century because the six bedrooms and It’s been my habit over many years of travelling to two suites are expansive by anyone’s standard. And dress for dinner. -

MARRAKECH Di N Guide

Maria Wittendorff Din guide til MARRAKECH muusmann FORLAG Maria Wittendorff Din guide til MARRAKECH muusmann FORLAG INDHOLD 57 Musée Tiskiwin 97 Dar Bellarj 7 Forord 138 Restauranter & cafeer – Museum Bert Flint 98 Dar Moulay Ali 59 Heritage Museum 99 Comptoir des Mines 140 Det marokkanske køkken 62 Maison de la Photographie 100 Festivaler 8 En lang historie kort 64 Musée de Mouassine 102 David Bloch Gallery 143 Gueliz 65 Musée Boucharouite 102 Galerie 127 143 Grand Café de la Poste 12 Historiske 67 Musée de la Femme 103 Musée Mathaf Farid Belkahia 144 La Trattoria seværdigheder 68 Musée des Parfums 104 Maison Denise Masson 145 +61 70 Aman – Musée Mohammed VI 105 La Qoubba Galerie d’Art 146 Gaïa 14 El Koutoubia 71 Observatoire Astronomie 106 Street art 146 Amandine 16 Almoravide-kuplen – Atlas Golf 147 Le Loft 17 Bymur & byporte 147 Le 68 Bar à Vin 19 Jamaa el-Fna 148 Barometre 108 Riads & hoteller 22 Gnawa 149 L’Annexe 72 Haver & parker 24 De saadiske grave 110 Riad Z 150 Le Petit Cornichon 26 Arkitektur 74 Jardin Majorelle 111 Zwin Zwin Boutique Hotel & Spa 150 L’Ibzar 32 El Badi 77 Jardin Secret 112 Riad Palais des Princesses 151 Amal 35 Medersa Ben Youssef 79 Den islamiske have 113 Riad El Walaa 152 Café Les Négociants 37 El Bahia 80 Jardin Menara 113 Dar Annika 153 Al Fassia 39 Dar El Bacha 82 Jardin Agdal 114 Riad Houma 153 Patron de la Mer – Musée des Confluences 83 Anima Garden 114 Palais Riad Lamrani 154 Moncho’s House Café 41 Garverierne 84 Cyber Park 115 Riad Spa Azzouz 154 Le Warner 42 Mellah 85 Jardin des Arts 116 La Maison -

Livret Voyage Maroc 2013

Stage collectif au Maroc Livret de voyage (du 15 au 22 avril 2013) Table des matières I. Carte..................................................................................................................................................3 II. Présentation du Maroc.....................................................................................................................4 1. Géographie...................................................................................................................................4 2. Géographie physique...................................................................................................................4 a) Montagnes...............................................................................................................................4 b) Plaines.....................................................................................................................................5 c) Littoral.....................................................................................................................................5 d) Climat.....................................................................................................................................5 3. Politique.......................................................................................................................................5 4. Économie.....................................................................................................................................6 a) Atouts et points -

Morocco Hides Its Secrets Well; Who Can Riad in Marrakesh, Morocco

INTERIORS TexT KALPANA SUNDER A patio with a pool at the centre of a Morocco hides its secrets well; who can riad in Marrakesh, Morocco. A riad imagine the splendour of a riad? Slip away is known for the lush greenery that from the hustle and bustle of aggressive is intrinsic to its open-air courtyard, street vendors and step into a cocoon of making it an oasis of peace. tranquillity. Frank Waldecker/Look/Dinodia Frank 74•JetWings•December 2014 JetWings•December 2014•75 Interiors AM IN THE lovely rose-pink Moroccan Above: View from the of terracotta roofs and legions of satellite dishes. town of Marrakesh, on the fringes of the rooftop of a riad that The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, the tallest lets you see all the Sahara, and in true Moroccan spirit, I’m way to the medina building in the city, is silhouetted against a crimson staying at a riad. Riads are traditional (the old walled part) sky; in the distance, the evocative sound of the Moroccan homes with a central courtyard of Marrakesh. muezzin called the faithful to prayer. With arched garden; in fact, the word riad is derived Below: A traditional cloisters, pots of lush tangerine bougainvillea and fountain in the inner from the Arabic word for garden. They offer courtyard of a riad in tiled courtyards, this is indeed a visual feast. refuge from the clamour and sensory overload of Fez, Morocco’s third the streets, as well as protection from the intense largest city, brings WHAT LIES WITHIN a sense of coolness cold of the winter and fiery warmth of the summer. -

The Berber Identity: a Double Helix of Islam and War by Alvin Okoreeh

The Berber Identity: A Double Helix of Islam and War By Alvin Okoreeh Mezquita de Córdoba, Interior. Muslim Spain is characterized by a myriad of sophisticated and complex dynamics that invariably draw from a foundation rooted in an ethnically diverse populace made up of Arabs, Berbers, muwalladun, Mozarebs, Jews, and Christians. According to most scholars, the overriding theme for this period in the Iberian Peninsula is an unprecedented level of tolerance. The actual level of tolerance experienced by its inhabitants is debatable and relative to time, however, commensurate with the idea of tolerance is the premise that each of the aforementioned groups was able to leave a distinct mark on the era of Muslim dominance in Spain. The Arabs, with longstanding ties to supremacy in Damascus and Baghdad exercised authority as the conqueror and imbued al-Andalus with culture and learning until the fall of the caliphate in 1031. The Berbers were at times allies with the Arabs and Christians, were often enemies with everyone on the Iberian Peninsula, and in the times of the taifas, Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, were the rulers of al-Andalus. The muwalladun, subjugated by Arab perceptions of a dubious conversion to Islam, were mired in compulsory ineptitude under the pretense that their conversion to Islam would yield a more prosperous life. The Mozarebs and Jews, referred to as “people of the book,” experienced a wide spectrum of societal conditions ranging from prosperity to withering persecution. This paper will argue that the Berbers, by virtue of cultural assimilation and an identity forged by militant aggressiveness and religious zealotry, were the most influential ethno-religious group in Muslim Spain from the time of the initial Muslim conquest of Spain by Berber-led Umayyad forces to the last vestige of Muslim dominance in Spain during the time of the Almohads. -

Expat Guide to Casablanca

EXPAT GUIDE TO CASABLANCA SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO 7 ENTRY, STAY AND RESIDENCE IN MOROCCO 13 LIVING IN CASABLANCA 19 CASABLANCA NEIGHBOURHOODS 20 RENTING YOUR PLACE 24 GENERAL SERVICES 25 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 26 STUDYING IN CASABLANCA 28 EXPAT COMMUNITIES 30 GROCERIES AND FOOD SUPPLIES 31 SHOPPING IN CASABLANCA 32 LEISURE AND WELL-BEING 34 AMUSEMENT PARKS 36 SPORT IN CASABLANCA 37 BEAUTY SALONS AND SPA 38 NIGHT LIFE, RESTAURANTS AND CAFÉS 39 ART, CINEMAS AND THATERS 40 MEDICAL TREATMENT 45 GENERAL MEDICAL NEEDS 46 MEDICAL EMERGENCY 46 PHARMACIES 46 DRIVING IN CASABLANCA 48 DRIVING LICENSE 48 CAR YOU BROUGHT FROM ABROAD 50 DRIVING LAW HIGHLIGHTS 51 CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY 53 WORKING IN CASABLANCA 59 LOCAL BANK ACCOUNTS 65 MOVING TO/WITHIN CASABLANCA 69 TRAVEL WITHIN MOROCCO 75 6 7 INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO TO INTRODUCTION 8 9 THE KINGDOM MOROCCO Morocco is one of the oldest states in the world, dating back to the 8th RELIGION AND LANGUAGE century; The Arabs called Morocco Al-Maghreb because of its location in the Islam is the religion of the State with more than far west of the Arab world, in Africa; Al-Maghreb Al-Akssa means the Farthest 99% being Muslims. There are also Christian and west. Jewish minorities who are well integrated. Under The word “Morocco” derives from the Berber “Amerruk/Amurakuc” which is its constitution, Morocco guarantees freedom of the original name of “Marrakech”. Amerruk or Amurakuc means the land of relegion. God or sacred land in Berber. -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr.