Complaint No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G-Sportbrochure Provincie West-Vlaanderen 2021.Pdf

GlSPORT in West-Vlaanderen SPORTAANBOD VOOR PERSONEN MET EEN BEPERKING 2021 Ook G-sporters beleven meer! Sport en beweging maakt gelukkig, verrijkt je vriendenkring en draagt bij aan je algemene gezondheid. Daarom willen wij zo veel mogelijk mensen in Vlaanderen en Brussel aanzetten tot regelmatig sporten en bewegen. Ben je op zoek naar een G-sportaanbod? In elke provincie en in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest is er een consulent Sporten zonder Drempels die het G-sportlandschap van de regio kent en je kan bijstaan in je zoektocht. Wil je graag zelf op zoek naar een sportclub die een G-sportaanbod heeft? Dan kan deze brochure jou hiermee helpen. In deze brochure kan je opzoeken welke (G-)sporten je in jouw buurt kan uitoefenen. Om een aanbod op maat te kunnen vinden, maakten we een onderscheid tussen verschillende doelgroepen en duidden we aan op welke manier G-sport zich situeert in de club. Naast het doelgroepspecifiek sportaanbod kan je ook een inclusief sportaanbod terugvinden. Want inclusie betekent dat sporters met en zonder beperking samen sporten. G-sport in de provincie West-Vlaanderen 3 Legende Leeftijd Alle leeftijden Ouder dan Sportclub G-sportclub: een sportclub die enkel een aanbod heeft voor personen met een beperking Sportclub met G-afdeling: een sportclub die G-sport aanbiedt naast het gewone sportaanbod Inclusieve sportclub: sporters met en zonder beperking sporten samen Sportaanbod R Sportaanbod in rolstoel Doelgroepen Autismespectrumstoornis Doven en slechthorenden Fysieke beperking Psychische kwetsbaarheid Verstandelijke -

Uw Gemeente in Cijfers: Wingene

Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene Inleiding Wingene : Wingene is een gemeente in de provincie West-Vlaanderen en maakt deel uit van het Vlaams Gewest. Buurgemeentes zijn Ardooie, Beernem, Lichtervelde, Oostkamp, Pittem, Ruiselede en Tielt (Tielt). Wingene heeft een oppervlakte van 68,4 km2 en telt 13.892 ∗ inwoners, goed voor een bevolkingsdichtheid van 203,0 inwoners per km2. 60% ∗ van de bevolking van Wingene is tussen de 18 en 64 jaar oud. De gemeente staat op de 433ste plaats y van de 589 Belgische gemeentes in de lijst van het hoogste gemiddelde netto-inkomen per inwoner en op de 117ste plaats z in de lijst van de duurste bouwgronden. ∗. Situatie op 1/1/2011 y. Inkomstenjaar : 2009 - Aanslagjaar : 2010 z. Referentiejaar : 2011 FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene Uw gemeente in cijfers: Wingene Inhoudstafel 1 Inhoudstafel 2 Bevolking Structuur van de bevolking Leeftijdspiramide voor Wingene 3 Grondgebied Bevolkingsdichtheid van Wingene en de buurgemeentes Bodembezetting 4 Vastgoed Prijs van bouwgrond in Belgi¨e Prijs van bouwgrond in Wingene en omgeving Prijs van bouwgrond : rangschikking 5 Inkomen Jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen per inwoner Jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen per inwoner voor Wingene en de buurgemeentes Evolutie van het jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen per inwoner FOD -

Lijst Erkende Inrichtingen Afdeling 0

Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF1 Amnimeat B.V.B.A. Rue Ropsy Chaudron 24 b 5 CS CP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF10 Eurofrost NV Izegemsestraat(Heu) 412 CS 8501 Heule KF100 BARIAS Ter Biest 15 CS FFPP, PP 8800 Roeselare KF1001 Calibra Moorseelsesteenweg 228 CS CP, MP, MSM 8800 Roeselare KF100104 LA MAREE HAUTE Quai de Mariemont 38 CS 1080 Molenbeek-Saint-Jean KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 CS RW 1840 Londerzeel KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 RW CS 1840 Londerzeel KF100159 LA BOUCHERIE SA Rue Bollinckx 45 CS CP, MP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF100210 H.G.C.-HANOS Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CC, PP, CP, FFPP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100210 Van der Zee België BVBA Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100227 CARDON LOGISTIQUE Rue du Mont des Carliers(BL) S/N CS 7522 Tournai KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 CS FFPP, RW 3210 Lubbeek KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 RW CS, FFPP 3210 Lubbeek KF100378 Lineage Ieper BVBA Bargiestraat 5 CS 8900 Ieper KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B CS CP, MP, RW 9040 Gent KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B RW CP, CS, MP 9040 Gent KF1004 PLUKON MOUSCRON Avenue de l'Eau Vive(L) 5 CS CP, SH 7700 Mouscron/Moeskroen 1 / 196 Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF100590 D.S. PRODUKTEN Hoeikensstraat 5 b 107 -

Michigan's ITA E R I T a G E Jouma{ of Tfie !French-Canaiian 1Feritage Society of !Micfzigan

Michigan's ITA E R I T A G E Jouma{ of tfie !French-Canaiian 1feritage Society of !Micfzigan Vol. 32 #3 Jul. 2011 Michigan's Habitant Heritage, Vol. 32, #3, July 2011 The Dudzeele and Straten Ancestry of Catherine de Baillon, Part 1 John P. DuLong, 1 FCHSM member ([email protected]) Nothing quite haunts a genealogist like an unsolved mystery. The Dudzeele family in the ancestry of Catherine de Baillon is one such mystery. The Dudzeele arms appear on a commemorative enameled plaque of Marguerite de Gavre d'Escomaix, the abbess of Ste-Gertrude at Nivelles, commissioned in 1461. She was the youngest daughter of Arnauld VI de Gavre d'Escomaix and Isabelle de Ghistelles, verified ancestors of Catherine de Baillon. 2 Many Americans and Canadians can claim descent from Catherine de Baillon and thus from the Dudzeeles. Figure I: Commemorative Plaque for Marguerite de Gavre d'Escornaix, the Abbess of Ste-Gertrude, Nivelles, displaying her ancestral arms and the images of the Madonna and child, Ste-Marguerite, a crouching dragon, and a kneeling abbess Marguerite in the middle, 1461. Heraldic evidence is often used to illustrate family history but is seldom useful in solving genealogical problems. However, in the ancestry of Catherine de Baillon, this plaque with five family arms displayed upon it was of particular genealogical value. The impaled Gavre d'Escornaix and Ghistellcs arms are for the parents of Marguerite. To the left these anns arc repeated individually. The franc quarter of the Ghistelles arms displays the Luxembourg arms and was thus an important piece of evidence proving a 1 The author would like to thank Barbara Lc Tarte and Kcshawn Mitchell, Document Service, Sladen Library, Henry Ford Health System. -

Plans Popp Aux Archives Générales Du Royaume / L

BE-A0510_002397_003492_FRE Plans Popp aux Archives générales du Royaume / L. Janssens Het Rijksarchief in België Archives de l'État en Belgique Das Staatsarchiv in Belgien State Archives in Belgium This finding aid is written in French. 2 Plans Popp aux Archives générales du Royaume DESCRIPTION DU FONDS D'ARCHIVES:................................................................3 Histoire du producteur et des archives............................................................4 Producteur d'archives..................................................................................4 Histoire institutionelle/Biographie/Histoire de la famille...........................4 Contenu et structure........................................................................................5 Mode de classement....................................................................................5 DESCRIPTION DES SÉRIES ET DES ÉLÉMENTS.........................................................7 POPP-KAARTEN.................................................................................................7 PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN, ARRONDISSEMENT ANTWERPEN.....................................7 PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN, ARRONDISSEMENT MECHELEN.......................................7 BRUSSEL-HOOFDSTAD............................................................................................7 PROVINCIE VLAAMS-BRABANT, ARRONDISSEMENT HALLE-VILVOORDE..................8 PROVINCIE WAALS-BRABANT, ARRONDISSEMENT NIJVEL.....................................19 PROVINCIE WEST-VLAANDEREN, -

Uittreksel Uit Het Notulenboek College Van Burgemeester En Schepen 8750 Wingene Zitting Van Maandag 26 Augustus 2019

Uittreksel uit het notulenboek College van burgemeester en schepen 8750 Wingene Zitting van maandag 26 augustus 2019 Hendrik Verkest, Burgemeester Lieven Huys, Hedwig Kerckhove, Brecht Warnez, Ann Mesure, Aanwezig: Schepenen Tom Braet, Voorzitter Bijzonder Comité Sociale Dienst Jurgen Mestdagh, Algemeen directeur Verontschuldigd: / Afwezig: / Het college, In besloten zitting, Tijdelijk verkeersreglement - wielerwedstrijd “Internationale Interclub” voor Elite met/zonder contract/Beloften - woensdag 4 september 2019 - Vaststelling Aanleiding en voorgeschiedenis De Stoempers organiseren op woensdag 4 september 2019 hun jaarlijkse wielerwedstrijd “Internationale Interclub” voor Elite met/zonder contract/Beloften. Op manifestaties zijn bijzondere verkeersmaatregelen vereist voor de verkeerscirculatie en voor de veiligheid van de weggebruikers én bezoekers. De wijkpolitie stelt een tijdelijke verkeersregeling voor. Bevoegdheid en juridische grond - het decreet lokaal bestuur van 22 december 2017, artikel 56, betreffende de bevoegdheden van het college van Burgemeester en Schepenen - de nieuwe Gemeentewet inzonderheid op artikelen 130 bis en 135 par 2 - de wet betreffende de politie over het wegverkeer gecoördineerd bij het KB van 16 maart 1968, inzonderheid op art 12 gewijzigd bij het KB van 30 december 1982 - het KB van 1 december 1975 houdende algemeen reglement op de politie van het wegverkeer, inzonderheid op titel III gewijzigd bij de KB’s van 23 juni 1978 en van 17 september 1988 laatst - het MB van 11 oktober 1976, waarbij de minimum -

Grensverleggend... INHOUDSTAFEL: Overzichtskaart 11

Stad Menen Grensverleggend... INHOUDSTAFEL: Overzichtskaart 11 Kennismaking 2 Natuur en platteland 13 Militair erfgoed 3 Leute en plezier 15 Architectuur en kunst 5 Eten en drinken 17 Musea 7 Shoppen 18 Stadsplan 8 Overnachten 19 Natuur en recreatie 9 In de omgeving... 21 1 Walcheren N256 Roosendaal 14 25 N283 Helmond 10 Neukirchen Bergen-op-Zoom 26 Nuenen Goes A270 Deurne Horst Straelen 8 Middelburg 28 Hilvarenbeek E 25 Vluyn E312 N277 11 s 37 ij 7 r 29 N271 A256 Zundert e N279 35 29 Wouwse e 9 A 58 t N258 Mierle r W 30 Peelland N265 A 73 38 Plantage aa f v o Schelde f 6 r a 35 Tu A 39 Oosterschelde Baarle-Nassau 31 5 34 33 Essen 1 Geldrop E 34 35 40 36 12 4 • N263 Veldhoven A 2 A 67 30 32 40 3 LONDON KINGSTON- 32 39 41 2 Hüls N 60 EINDHOVEN34 Sloehaven 33 13 E 34 M25 upon-HULL Vlissingen Asten 37 R R Someren Venlo 509 i e A 40 31 j 38 n E 34 E312 u Heeze 509 v s e e l CANTERBURY r N 12 b A 67 Kempen Zuid Beveland A 58 i 221 n 2 15 M 2 d Wuustwezel Waalre E 25 i N289 Ramsgate n KREFELD g A 4 32 Grefrath Maidstone ling A 2 M20 Wie E 19 Tegelen 509 Tönisvorst N 60 N119 Reusel Eersel 2 Ashford Dover Westerschelde A 1 34 Panningen THALYS Kalmthout Merksplas De Groote Peel NOORDZEE 11 E 34 N266 Folkestone Brecht Valkenswaart 35 Z N277 Nettetal U.K. -

1E Stratenloop Wingene

1e Stratenloop Wingene - 1 september 2007 10 KM PL Naam Woonplaats GBJ CAT P/CAT 1 Caby Dimitri Avelgem 76 M 1 2 De Blander Guy Meerbeke 67 M 2 3 Verkaemer Bart Waregem 76 M 3 4 Luttun Evert Wingene 75 M 4 5 Sierens Dirk Beernem 65 M 5 6 Hoste Franky Wingene 61 M 6 7 Decraemer Marnic Beernem 62 M 7 8 Lannoo Dirk Oostrozebeke 63 M 8 9 Royaert Geert Tielt 70 M 9 10 Cool Andy Roeselare 76 M 10 11 Taelman Lucien Waregem 57 M 11 12 Van Bruwaene Rudy Tielt 52 M 12 13 Vromman Jan Pittem 86 M 13 14 Chanterie Marc Wingene 60 M 14 15 Ballegeer Kurt Beernem 69 M 15 16 Van Cauwenberghe Filip Wingene 68 M 16 17 Vandenbogaerde Yves Menen 63 M 17 18 Viaene Mayko Waregem 77 M 18 19 De Craemer Stefaan n/a 68 M 19 20 De Vogelaere Joris Waregem 62 M 20 21 Lefevere Rik Tielt 70 M 21 22 Algoedt Dany Wingene 62 M 22 23 Vanwalleghem Alexander Veldegem 80 M 23 24 Callens Rob Waregem 91 M 24 25 Beunens Xavier Kortrijk 72 M 25 26 Rysman Johan Waregem 54 M 26 27 Delodder Bart Waregem 79 M 27 28 Devilder Patrick n/a 62 M 28 29 Brandt Francky Beernem 62 M 29 30 Verhaeghe Eddy Wingene 62 M 30 31 Frickelo Geert Oostkamp 64 M 31 32 Van Overbeke Ruben Pittem 80 M 32 33 De Laere Peter n/a 68 M 33 34 Maes Luc Meulebeke 52 M 34 35 Dombrecht Francis n/a 79 M 35 36 Van Doorn Winny Wingene 69 M 36 37 Verbauweede Marianne Dentergem 58 V 1 38 Vandevoorde Ruben Pittem 81 M 37 39 De Laere Annick Anzegem 74 V 2 40 Ally Geert Oostkamp 64 M 38 41 Clincke Ray Ruiselede 58 M 39 42 Baele Carl Beernem 68 M 40 43 Vanderplaetse Paul Beernem 55 M 41 44 Van Hiel Paul n/a 70 M 42 45 Luynckx -

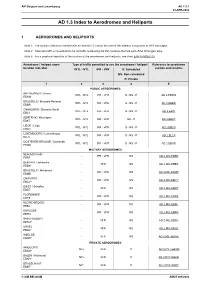

AD 1.3 Index to Aerodromes and Heliports

23-APR-2020 AIP Belgium and Luxembourg AD 1.3-1 23-APR-2020 AD 1.3 Index to Aerodromes and Heliports 1 AERODROMES AND HELIPORTS Note 1: The location indicators marked with an asterisk (*) cannot be used in the address component of AFS messages. Note 2: National traffic is considered to be all traffic not leaving the EU countries that are part of the Schengen area. Note 3: For a graphical depiction of the location of the aerodromes and heliports, see chart ENR 6-INDEX.09. Aerodrome / heliport name Type of traffic permitted to use the aerodrome / heliport Reference to aerodrome location indicator INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S: Scheduled section and remarks NS: Non-scheduled P: Private 1 2 3 4 5 PUBLIC AERODROMES ANTWERPEN / Deurne INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBAW EBAW BRUSSELS / Brussels-National INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBBR EBBR CHARLEROI / Brussels South INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBCI EBCI KORTRIJK / Wevelgem INTL - NTL IFR - VFR NS - P AD 2.EBKT EBKT LIÈGE / Liège INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBLG EBLG LUXEMBOURG / Luxembourg INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.ELLX ELLX OOSTENDE-BRUGGE / Oostende INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBOS EBOS MILITARY AERODROMES BEAUVECHAIN - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBE EBBE BERTRIX / Jehonville - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBX EBBX* BRUSSELS / Melsbroek - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBMB EBMB CHIÈVRES - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBCV EBCV* DIEST / Schaffen - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBDT EBDT FLORENNES - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBFS EBFS KLEINE-BROGEL - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBL EBBL KOKSIJDE - -

Ecological Restoration in Flanders

Ecological Restoration in Flanders Kris Decleer (editor) Mededelingen van het Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek INBO.M.2008.04 1 Acknowledgements This publication was made possible by the contributions and support of the following people and organisations. Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO) Peter Adriaens, Niko Boone, Geert De Blust, Piet De Becker, Nicole De Groof, Kris Decleer, Luc Denys, Myriam Dumortier, Robin Guelinckx, Maurice Hoffmann, Lon Lommaert, Tanja Milotic, Sam Provoost, Geert Spanoghe, Erika Van den Bergh, Kris Van Looy, Tessa Van Santen, Jan Van Uytvanck, Kris Vandekerkhove, Bart Vandevoorde. Agency for Nature and Forests (ANB) Mario De Block, Evy Dewulf, Jeroen Geukens, Valérie Goethals, Lily Gora, Jean-Louis Herrier, Elvira Jacques, Hans Jochems, Marc Leten, Els Martens, Lieven Nachtergale, Hannah Van Nieuwenhuyse, Laurent Vanden Abeele, Eddy Vercammen, Tom Verschraegen, LIFE project team ‘DANAH’ Flemish Land Agency (VLM) Carole Ampe, Ingrid Beerens, Griet Celen, Hilde Heyrman, Joy Laquière, Daniël Sanders, Hilde Stulens, Toon Van Coillie, Inge Vermeulen Natuurpunt (NP) Tom Andries, Dirk Bogaert, Gaby Bollen, Tom De Beelde, Joost Dewyspelaere, Gert Ducheyne, Frederik Hendrickx, Guido Tack, Steven Vangompel, Christine Verscheure, Stefan Versweyveld University of Ghent Eckhart Kuijken University of Antwerp Tom Maris City of Ghent Bart De Muynck 2 Content page Foreword 5 I. Policy framework for ecological restoration in Flanders 7 I.1. Legal obligations 7 ● Spatial planning and zoning maps 7 ● The Flemish Ecological Network 7 ● Natura 2000 7 I.2. Main instruments for ecological restoration in Flanders 9 ● Acquisition of land for the creation of nature reserves 9 ● Management of nature reserves 9 ● Ecological restoration as a side effect of large public works 9 ● Compensation obligation 9 ● Schemes for land development and land development for nature 9 ● EU (LIFE) 10 ● Private-public cooperation agreements for management and restoration 10 ● Regional Landscapes 10 II. -

Lijst Effectieve Leden Wbe Houtland 28.06.2019

1 LIJST EFFECTIEVE LEDEN WBE HOUTLAND 28.06.2019 Nr. Jachtveldnummer Voornaam Naam Straat Hnr. Postco Gemeente Tel.nr Email WBE de 1 60 / 69 Patrick G. Daenens Warandestraat 1 8820 Torhout 050 212229 [email protected] 2 43 J.-Jacques Matthieu de Oostendestraat 390 8820 Torhout 0477 37 76 40 [email protected] 3 47/20/62/71/75/76 Bart ForéWWwynen Wynendael Zeeweg Zuid 21 8211 Aartrijke 0479 21 93 15 [email protected] 4 23/33/37/90/91/92/93 Roger Denooe Demaerestraat 17 8211 Aartrijke 050 211211 [email protected] 5 120 Christophe Maertens Wijngaard 36 9831 Deurle 09 2337445 [email protected] 6 9 / 85 Kamiel Buffel Brugsesteenweg 30 8433 Middelkerke 0498 12 86 68 philiptimmerm [email protected] 7 39 Luc Bolle A Coussestraat 78 8480 Ichtegem 051 58 18 19 [email protected] [email protected] 8 7 Astrid de Busschere Woudweg naar 2 8490 Snellegem 0475 943499 [email protected] Loppem 9 21 Sylvie Meuris F. Sanderlaan 7 8200 Brugge 0475 780957 [email protected] 10 64 / 81 Francois Blontrock Joe Englischstraat 15 8000 Brugge 0478 244159 [email protected] 11 18 / 16 Luc Rogiers Bergenstraat 94 8020 Ruddervoorde 0499 334274 [email protected] 12 66 Rik Bolle Keibergstraat 32 8480 Ichtegem 0472 43 84 95 [email protected] 13 11 Thierry Van Caloen Rolleweg 7 8210 Loppem 050 383520 [email protected] 14 113 Benny Willaert Aartrijksesteenweg 112 8490 Jabbeke 0472 57 88 98 [email protected] 15 56 Luc Vansevenant Roesdammestraat 13 8630 Veurne 0477 222144 [email protected] -

Business Centres in the Province of West-Flanders

KNO(!KKE-HEIST BLANKENBERGE Business Centre 't Walletje Baudouin Canal Business Centre Ostend (OC) E34 BEVEREN Bluebridge - Ostend Science Park (! (! OSTEND (! Business Centre Ostend - Zandvoordestraat (! (! (!(! (!BRUGES A10 E4(!03(!(!(!(! (! E34 (! EE(!KLO Vaartdijk Business Centre Business Centre Veurne - Acasus (! E40 Business Centre Ostend - Kuipweg Canal Ghent-Ostend (! (! (!TEMSE Business Centre TVELT E40 Office 407 (! BLACKBOXX (! ! (! Business Centre 3koningen ((! (! IC Grote Beer Business Centre Bruges (! LOKCEORERNE BRUGES (! (! Business Centre Veurne (! (! Bus(!iness Centre Bruges (OC) (! (! E17 TORHOUT E40 (! (! (! (!(!(!(! (!(! Business Centre Diksmuide E403 (!(!(! (! (! Business Centre Wingene (!(!(!(!(! BRUGGE.INC VEURNE DIKSMUIDE Business Centre Wingene (Driebeck) (!W(!ork-Around (! (!(! (! (! (! (! DENDERMONDE DEINZE (! (!(!(!(! (! (! IJzer T(!IELT (!(! WETTERE(!N Business Centre Roeselare REGUS Bruges Express (! Katelijnepoort Business Centre (! Vlaemynck Business Cen(!tre (! Vaartdijk Business Centre (! ROESELARE (! The Vibe Business Centre Izegem (! Business Centre Roeselare (OC) E17 (! (!(! Atelier12 (! REGUS Roeselare West Wing Park ! (! Leie (!((! Business Centre Poperinge d'Office Business Centre Ieper E40 ASSE Business Centre Waregem (! ZOTTEGEM (! (! WA(!REG(!EM (! Stede 51 (! POPERIN(!GE IEPER (! OUDENAARDE (! A19 (! E17 Stede 51 ! (!(!(! (! CORE KORTRIJK (! (!(!((! (! ABC-Waregem (! (! Business Centre Waregem (Region) Studio Ko - Coworking Kortrijk MENEN Leie KORTRIJK Hangar K Business Centre Kortrijk (! Start