Homage to Iowa: the Inside Story of Ignacio V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barcelona and the Paradox of the Baroque by Jorge Luis Marzo1

Barcelona and the Paradox of the Baroque By Jorge Luis Marzo1 Translation by Mara Goldwyn Catalan historiography constructed, even from its very beginnings, the idea that Catalunya was not Baroque; that is, Baroque is something not very "proper" to Catalunya. The 17th and 18th centuries represent the dark Baroque age, in contrast with a magnificent Medieval and Renaissance era, during which the kingdom of Catalunya and Aragón played an important international role in a large part of the Mediterranean. The interpretation suggests that Catalunya was Baroque despite itself; a reading that, from the 19th century on - when it is decided that all negative content about Baroque should be struck from the record in order to transform it into a consciously commercial and urban logo - makes implicit that any reflection on such content or Baroque itself will be schizophrenic and paradoxical. Right up to this day. Though the (always Late-) Baroque style was present in buildings, embellishments and paintings, it however did not have an official environment in which to expand and legitimate itself, nor urban spaces in which to extend its setup (although in Tortosa, Girona, and other cities there were important Baroque features). The Baroque style was especially evident in rural churches, but as a result of the occupation of principle Catalan plazas - particularly by the Bourbon crown of Castile - principal architectonic realizations were castles and military forts, like the castle of Montjuic or the military Citadel in Barcelona. Public Baroque buildings hardly existed: The Gothic ones were already present and there was little necessity for new ones. At the same time, there was more money in the private sphere than in the public for building, so Baroque programs were more subject to family representation than to the strictly political. -

Catalonia 1400 the International Gothic Style

Lluís Borrassà: the Vocation of Saint Peter, a panel from the Retable of Saint Peter in Terrassa Catalonia 1400 The International Gothic Style Organised by: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya. From 29 March to 15 July 2012 (Temporary Exhibitions Room 1) Curator: Rafael Cornudella (head of the MNAC's Department of Gothic Art), with the collaboration of Guadaira Macías and Cèsar Favà Catalonia 1400. The International Gothic Style looks at one of the most creative cycles in the history of Catalan art, which coincided with the period in western art known as the 'International Gothic Style'. This period, which began at the end of the 14th century and went on until the mid-15th century, gave us artists who played a central role in the history of European art, as in the case of Lluís Borrassà, Rafael Destorrents, Pere Joan and Bernat Martorell. During the course of the 14th century a process of dialogue and synthesis took place between the two great poles of modernity in art: on one hand Paris, the north of France and the old Netherlands, and on the other central Italy, mainly Tuscany. Around 1400 this process crystallised in a new aesthetic code which, despite having been formulated first and foremost in a French and 'Franco- Flemish' ambit, was also fed by other international contributions and immediately spread across Europe. The artistic dynamism of the Franco- Flemish area, along with the policies of patronage and prestige of the French ruling House of Valois, explain the success of a cultural model that was to captivate many other European princes and lords. -

Art History of Spain in the History of Western Art, Spain

Art History of Spain In the history of Western Art, Spain occupies a very significant and distinct position; after the French and the Italians, the Spanish are probably the most important contributors to the development and evolution of art in the Western Hemisphere. Over the centuries, numerous Spanish artists have contributed heavily to the development of European art in almost all the “major” fields like painting, sculpture and architecture. While Spanish art has had deep linkages with its French and Italian counterparts, Spain’s unique geographic location has allowed it to evolve its own distinct characteristics that set it quite apart from other European artistic traditions. Spain’s fascinating history of conquest and trade is inextricably linked to the evolution of its art. Cave Paintings of Altamira, Spain The earliest inhabitants of what is now modern-day Spain were known for their rich art traditions, especially with respect to cave-paintings from the Stone Age. The Iberian Mediterranean Basin in the regions of Aragon and Castile-La Mancha in eastern Spain, and the world famous Altamira Cave paintings in Cantabria are both UNESCO World Heritage sites that showcase vivid cave paintings from the Stone Age. Pre-Romanesque Period Over the course of history, Spain has been deeply influenced by the culture art of its neighbors, who were more often than not its conquerors. The Roman control over Hispania, from 2nd century BC to 5th century AD, had a deep influence on Spain, especially in its architecture dating from that period. The Aqueduct of Segovia, Alcantara Bridge and the Tower of Hercules Lighthouse are some of the important monuments from that period that still survive to-date. -

Catalonian Architectural Identity

Catalan Identity as Expressed Through Architecture Devon G. Shifflett HIST 348-01: The History of Spain November 18, 2020 1 Catalonia (Catalunya) is an autonomous community in Spain with a unique culture and language developed over hundreds of years. This unique culture and language led to Catalans developing a concept of Catalan identity which encapsulates Catalonia’s history, cuisine, architecture, culture, and language. Catalan architects have developed distinctly Catalan styles of architecture to display Catalan identity in a public and physical setting; the resulting buildings serve as a physical embodiment of Catalan identity and signify spaces within Catalan cities as distinctly Catalonian. The major architectural movements that accomplish this are Modernisme, Noucentisme, and Postmodernism. These architectural movements have produced unique and beautiful buildings in Catalonia that serve as symbols for Catalan national unity. Catalonia’s long history, which spans thousands of years, contributes heavily to the development of Catalan identity and nationalism. Various Celtiberian tribes initially inhabited the region of Iberia that later became Catalonia.1 During the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), Rome began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, which was occupied by the Carthaginians and Celtiberians, and established significant colonies around the Pyrennees mountain range that eventually become Barcelona and Tarragona; it was during Roman rule that Christianity began to spread throughout Catalonia, which is an important facet of Catalan identity.2 Throughout the centuries following Roman rule, the Visigoths, Frankish, and Moorish peoples ruled Catalonia, with Moorish rule beginning to flounder in the tenth-century.3 Approximately the year 1060 marked the beginning of Catalan independence; throughout this period of independence, Catalonia was very prosperous and contributed heavily to the Reconquista.4 This period of independence did not last long, though, with Catalonia and Aragon's union beginning in 1 Thomas N. -

Uvic-Ucc | Universitat De Vic - Universitat Central De Catalunya

CONTENTS WHAT WE’RE LIKE BARCELONA AND BEYOND Pere Virgili Ruth Marigot WELCOME to our city, to our country and to our home! Working together with the newspaper ARA, at BCU we’ve prepared this guide to help you to enjoy Barcelona and Catalonia like Barcelona in 10 concepts ................................................................. 4-5 On foot, running and by bike ...................................... 18-19 a native. Our universities in figures ................................................................. 6-7 From Barcelona to the world ................................... 20-21 We aim to help you feel Secret Barcelona ................................................................................................... 8-9 Why did I decide to stay here? ........................................... 22 welcome and make things easier Instagram-worthy spots ......................................................................... 10 Where can I live? ........................................................................................................ 24 for you. So, in the following pages, Don’t miss out ......................................................................................................... 12-16 Catalonia: more than just a club ....................................... 26-27 you’ll find plenty of information TALENT CITY ROSES, FIRE AND... about what to do and see, and where and when to do and see it. Pere Tordera Francesc Melcion Because historically we’ve always been a land of welcome and we’re very happy that you’ve -

Repoblica Espanola

REPOBLICA ESPANOLA Sight of Giiell Park Photo. Mas ARCELONA, the weahhy capital of the four Catalan provinces, enjoys a splendid situation opposite the Mediterranean, in a rich undulating plain, between two rivers, tile BesSs and the Llobregat, and the two natural watch-towers of the Tibidabo and Montjuich mountains. Its favourable climate, with a mean annual temperature of between 16 and 17 degrees, and sky of rare clearness and beauty make the city an exceptionally agreeable place of residence in all the seasons of the year. Without any very exact historic data it is more or less certain that Barcelona was the capital of the Layetanos. In the first centuries of our era, under the name of Favencia Julia Augusta Pia Barcino, it enjoyed a position of great importance, later serving as the court of the Visigothie kings. Suffering the fate of the rest of the peninsula, it was dominated Sight of Catalufia Square A Public Swimming-Pool Photo. Roisin by the Arabs, and passed through all the vicissitudes of the struggle varied requirements of metropolitan life: hotels, banks, big stores, etc.; between Franks and Saracens, until in the year 874 Count Wilfred, its numerous workshops and factories which bring the bustle and mo- known as the Hairy, obtained the privilege of declaring hereditary the vement of city life to every part of the great town. The centre of Barce. fiefs and benefices of the counties of the Spanish Mark. With this was lona's activity is the Plaza de Catahifia; the largest square in Spain, initiated the Catalan dynasty, and Barcelona rose to great importance recently embellished with great gardens and fine groups of sculpture. -

Toledo Cathedral on the International Stage

Breaking the Myth: Toledo Cathedral on the International Stage Review of: Toledo Cathedral: Building Histories in Medieval Castile by Tom Nickson, University Park, Pensylvannia: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2015, 304 pp., 55 col. illus., 86 b.&w. illus., $89.95 Hardcover, ISBN: 978-0-271-06645-5; $39.95 Paperback, ISBN: 978-0-271-06646-2 Matilde Mateo In 1865, the British historian of architecture George Edmund Street (1824-1881) confessed in his Some Account of Gothic Architecture in Spain that he was not expecting to see any example of the great Gothic architecture of the thirteenth century in his first trip to that country until his way back home, when he could set his eyes again on the cathedrals of Chartres, Notre-Dame of Paris, or Amiens. This assumption, however, was shattered when he visited Toledo Cathedral for the first time because this church, to his surprise and in his own words, was ‘an example of the pure vigorous Gothic of the thirteenth century’, and ‘the equal in some respects of any of the great French churches.’ As he admitted, Toledo Cathedral was a startling and pleasant discovery that led him to declare: ‘I hardly know how to express my astonishment that such a building should be so little known [among my compatriots].’1 One has to wonder what would have been Street´s reaction should he have learned that, despite his account and praise of Toledo Cathedral, it would take the astounding length of time of one hundred and fifty years for that gap in knowledge to be filled? Indeed, it has only been recently, in 2015, that a comprehensive monograph in English of Toledo Cathedral has been published. -

Arquitectura Modernista: What Was/Is It? Judith C Rohrer

Permanent Secretariat Av. Drassanes, 6-8, planta 21 08001 Barcelona Tel. + 34 93 256 25 09 Fax. + 34 93 412 34 92 Strand 2: The Historiography of Art Nouveau (looking back on the past) Arquitectura Modernista: What Was/Is It? Judith C Rohrer The publication of Oriol Bohigas’ Arquitectura Modernista in 1968 marked a key moment in the historiography of Catalan “Modernisme”1. Here for the first time was a monographic study of the architecture of the turn of the century period along with extensive, indeed seductive, photographic documentation by Leopold Pomés, a detailed chronology of the period setting the architecture in both local and international context, and a biographical section which served as a preliminary catalog of the known works of modernista architects and their dates of execution. That this monograph launched a spate of serious research into the relatively unknown architects of the modernista era can be seen in the second, totally revised, edition of the book (1973), now retitled Reseña y Catálogo de la Arquitectura Modernista, as well as in the third (1983) where the list of modernista practitioners grew exponentially from 44 to 80 to 175 thanks to a flurry of archival inventories and individual monographs spurred on by Bohigas’ example.2 It was the beginning of a sustained and rigurous investigation of the subject that continues unabated to this day. Arquitectura Modernista provided a needed focus on a broad range of Catalan architectural practice and production. It was written, the author explained, to counter the tendency, in a time of burgeoning international interest in the history of the modern movement and its sources, to think of 1Oriol BOHIGAS, Arquitectura Modernista, Barcelona, Lumen, 1968 2Oriol BOHIGAS, Reseña y Catálogo de la Arquitectura Modernista, Barcelona, Lumen, 1973; Second edition, with ampliación y revisión del apéndice biografico y la lista de obras by Antoni Gonzalez and Raquel Lacuesta, Barcelona, Lumen, 2 vols., 1983. -

The Influences of Gothic and Renaissance Textiles on Sgraffito in Catalan Modernisme1

38 OPEN SOURCE LANGUAGE VERSION > CATALÀ The Influences of Gothic and Renaissance Textiles on Sgraffito in Catalan Modernisme1 by Daniel Pifarré Yañez PhD in History of Art, University of Barcelona - GRACMON 1 This article is the fruit of Some of the most renowned names in Catalan culture and artistic creation have extended research deriving emerged from the Modernista period, with Catalan architecture becoming one from a previous study for the catalogue MALLART, of the most recognisable and most admired forms of the discipline at home Lucila (ed.), Josep Puig i and abroad. The role of the architect in Catalonia in 1900 is crucial to the story. Cadafalch: visió, identitats, The architect exerted creative control over the entire decorative programmes cosmopolitisme, Museu de Mataró, Mataró, 2018. It also of his buildings, either designing them himself or delegating the work to forms part of the research specialists in different disciplines. Out of the wide range of decorative arts project Entre ciutats: paisatges available to professionals for the embellishment of façades and interiors, the culturals, escenes i identitats technique of sgraffito became one of the most commonly utilised to cover the (1888-1929), funded by the Ministry of Economy and surfaces of walls, with the world of nature providing the most typical source Competitiveness (HAR2016- for ornamental compositions. The aim of this paper is to show clearly that the 78745-P). artists and craftsmen of the Modernista period, when they created sgraffito, very 2 This is the central theme frequently found an extremely rich field of decorative solutions in early textiles, of the author’s doctoral thesis. -

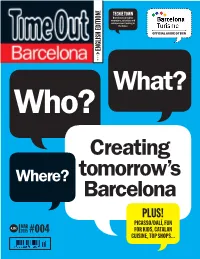

Creating Tomorrow's Barcelona

TECHIE TOWN Barcelona is a hub for innovators, scientists and entrepreneurs looking to the future OFFICIAL GUIDE OF BCN ENGLISH EDITION! ENGLISH What? Who? Creating Where? tomorrow’s Barcelona PLUS! PICASSO/DALÍ, FUN MAR 4,95€ 2015 #004 FOR KIDS, CATALAN CUISINE, TOP SHOPS... 2 Buy tickets & book restaurants at www.timeout.com/barcelona & www.visitbarcelona.com Time Out Barcelona in English The Best March 2015 If you’re in Barcelona on a family trip, we show you of BCN some of the best places to take your children p. 26 Features 14. Looking into the future Meet the people, projects and places at the heart of the city’s technological advances. 20. Fisticuffs! BCN saw a boxing boom in the Ɓrst half of the 20th century – Julià Guillamon gloves up. 24. Fried to perfection Laura Conde introduces us to the churro, Spanish cousin of the doughnut. 26. Young visitors Barcelona is full of places to keep kids happy – Jan Fleischer suggests a few of the best. 28. Compare and contrast Alx Phillips previews a new show exploring the parallel lives of Picasso and Dalí. CHASSEROT SCOTT Regulars 30. Shopping & Style 34. Things to Do 42. The Arts 54. Food & Drink 62. Clubs 64. LGBT IVAN GIMÉNEZ IVAN 65. Getaways PUKAS SURF BARCELONA Barcelona is a fantastic place for Ɓtness fans to Welcome to the wondrous world of the churro, 66. BCN Top Ten get out and about p. 34 the local version of the doughnut p. 24 Via Laietana, 20, 1a planta | 08003 Barcelona | T. 93 310 73 43 ([email protected]) Impressió LitograƁa Rosés Publisher Eduard Voltas | Finance manager Judit Sans | Business manager Mabel Mas | Editor-in-chief Andreu Gomila | Deputy editor Hannah Pennell | Features & web Distribució S.A.D.E.U. -

Civil Gothic Architecture in Catalonia, Mallorca and Valencia (13Th-15Th Centuries)

CATALAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 13: 27-42 (2020) Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona DOI: 10.2436/20.1000.01.164 · ISSN (print): 2013-407X · e-ISSN: 2013-4088 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/CHR Civil Gothic architecture in Catalonia, Mallorca and Valencia (13th-15th centuries) Eduard Riu-Barrera* Archaeologist and historian Received 21 February 2019 · Accepted 25 September 2019 Abstract This article is an introduction to the civil or secular Gothic architecture in the Catalan Lands (Catalonia, Mallorca and the region of Valencia) from the 13th to 15th centuries and its spread to Italy under the influence or dominion of the royal house of Barcelona. A general introduction to its formal and constructive features is followed by a sketch of the genesis and morphological diversity of some of the main building typologies, along with a presentation of the most important castles, palaces, urban homes, town halls and govern- ment buildings, mercantile exchanges and baths. Keywords: Catalan civil Gothic architecture, bath, urban house, town hall, castle, Generalitat, mercantil exchange (Llotja), palace General considerations Both religious and secular architecture developed on con- tinental Catalonia and in the region of Valencia, as well as Just like most old architectures, Gothic architecture is on the Balearic Islands, specifically the island of Mallorca, primarily defined and known through religious works, following quite similar formulations. that is, through churches and their associated sacred Even though this architectural corpus is a subset within spaces. There is no question that among all the buildings what is known as the southern Gothic, it has a very dis- that stylistically fall within the Gothic, churches repre- tinct personality which was spread to or influenced other sent the peak and boast the most art, but they actually di- lands to differing degrees by the royal house of Barcelona verge little from civil or secular Gothic architecture. -

Veronia 2010 Maquetación 1 11/04/11 10:25 Página 17

veronia 2010_Maquetación 1 11/04/11 10:25 Página 17 MODERNISM IN CATALONIA With the industrialization of Catalonia in the 19th century, Barcelona was quick to assess its urban needs. City walls were torn down and the city itself widened, resulting in an urban landscape still in evidence today. By means of exhibits and direct communication with Europe, the most recent artistic tendencies were applied. Around 1900 three great Catalan creators, Gaudí, Domenech, and Puig, expanded “modernism” far beyond a mere import of an artistic style or translation of an artistic term. Their style extended to other city centers of Catalonia. Day 1 Arrival in Barcelona and overnight. Day 4 Today we will concentrate on the most famous son of Figueres, the great, controversial surrealist painter Day 2 Our point of entry to Barcelona is the historical Salvador Dalí. The Theater-Museum was created and district. We will see one of the most beautiful examples designed by the artist to accommodate a large part of of the Catalan Gothic style with the imposing Santa his works, and to serve as his burial site. María del Mar church. From there we will head A stroll through the small city will take us to some of towards the Gothic quarter where we will see the Figuere’s modernist works such as the Casa Cusí i Cathedral, the Palau de la Generalitat, the Town Hall, Salleras or the former slaughterhouse which today serves the small streets that lead to the Plaza Real. as a cultural center. La Rambla, an area joining the statue of Columbus Possibility of organizing lunch in Figueres.