Domestic Wells Have High Probability of Pumping Septic Tank Leachate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Septic Tanks, Are a Contributing Factor to Phosphorus As Well As Site Specific Conditions

Scotland’s centre of expertise for waters Practical measures for reducing phosphorus and faecal microbial loads from onsite wastewater treatment system discharges to the environment A review i Scotland’s centre of expertise for waters This document was produced by: Juliette O’Keeffe and Joseph Akunna Abertay University Bell Street, Dundee DD1 1HG and Justyna Olszewska, Alannah Bruce and Linda May Centre for Ecology & Hydrology Bush Estate Penicuik Midlothian EH26 0QB and Richard Allan Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW) The James Hutton Institute Invergowrie Dundee DD2 5DA Research Summary Key Findings Onsite wastewater treatment systems (OWTS), the majority of local flow and load characteristics of the effluents streams, which are septic tanks, are a contributing factor to phosphorus as well as site specific conditions. With that in mind, measures and faecal microbial loads. OWTS contribute to waterbodies such as awareness raising, site planning, and maintenance failing to meet Water Framework Directive (WFD) objectives are likely to contribute to reduction of impact of OWTS on and as such, measures to improve the quality of OWTS the environment. The level of load reduction possible from discharges are required. Literature has been reviewed for measures such as awareness raising is difficult to quantify, a range of measures designed to reduce phosphorus and but it is low-cost and relatively easy to implement. Those most pathogen concentrations in effluent from OWTS. A feasibility effective for phosphorus and pathogen removal are post-tank assessment focussed on their application, effectiveness, measures that maximise physical removal, through adsorption efficiency, cost and ease of adaptation. A wide range of and filtering, and maintain good conditions for biological measures have been identified that could potentially improve breakdown of solids and predation of pathogens. -

Leachate Quantities After Closure of a Landfill

Leachate Quantities after Closure of a Landfill Ali Khatami, Ph.D., P.E., The leachate quantities for SCS Engineers the period of 2010 through 2014 were obtained and Criteria for the solid waste analyzed. The data clearly landfills (40 CFR Part 258 shows a downward trend of or the Subtitle D Federal) leachate quantities following have been around for over 30 closure, as would be years and many municipal expected. Leachate collected solid waste (MSW) landfills from the landfill during have been constructed 2010 was reported on a with lining systems in monthly basis when leachate accordance with the Subtitle quantities after closure were D requirements. However, still high and needed to be very few Subtitle D landfills removed from the facility have been entirely closed for disposal every month. with final covers that include However, leachate quantities a geomembrane barrier layer. rapidly decreased and The significance of the final Glades County Landfill after closing. monthly shipment of leachate covers with geomembrane was no longer necessary; is that percolation of rain Since the landfill was closed in one single construction event, rain water instead, leachate was removed when water into the landfill essentially the storage tank reached a point that stops following completion of the percolation was essentially eliminated almost instantaneously considering the leachate had to be removed and final cover. Assuming the final cover quantities reported. Therefore, the the 20-year time frame the landfill was system remains intact, leachate that data did not have monthly values, but continues to be generated after closure open. It is important to note that the maximum thickness of waste in the clusters of several-months data. -

INVESTIGATION of ANAEROBIC PROCESSES in SEPTIC TANK AS a WASTEWATER TREATMENT OPTION Odenigbo C

International Journal of Civil Engineering, Construction and Estate Management Vol.6, No.1, pp.22-25, May 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) INVESTIGATION OF ANAEROBIC PROCESSES IN SEPTIC TANK AS A WASTEWATER TREATMENT OPTION Odenigbo C. Department of Civil Engineering, Enugu State University of Science and Technology ABSTRACT: This study aims to find out the anaerobic processes in septic tank as a wastewater treatment plant. Samples were collected from both a septic tank and soakaway pit. Thus, after the collection of samples from the location, waste water analysis was conducted on the two water samples A and B respectively. The results obtained on the water samples showed that sample A under physical analysis using thermometer, pH meter, conductivity meter etc, has a higher physical characteristics value according to table 4.1, than that of sample B. more also from the chemical analysis seen in table 4.1 sample A has a higher BOD, COD and DO values more than that of sample B. Therefore this suggests that biological treatment processes was efficient in that septic tank and as such waste water discharged to the environment, will be harmless to the inhabitants in that environment. KEYWORDS: Anaerobic, Septic Tank, Sewage, Treatment. INTRODUCTION Human waste or more technically referred to as Excrets, which is made up of a solid matter, faeces and liquid matter, urine and is essentially an organic compound. The constituents making up the compound are carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and hydrogen. Also present are fats, carbohydrates, enzymes, proteins, trace elements, pathogens and many different bacteria. -

Properly Managing Your Septic Tank System

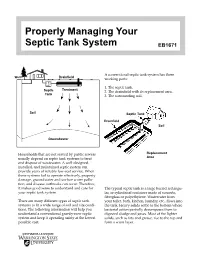

Properly Managing Your Septic Tank System EB1671 A conventional septic tank system has three Well Drainfield working parts: 1. The septic tank. Treatment Septic 2. The drainfield with its replacement area. Tank 3. The surrounding soil. Soil Septic Tank Drainfield Soil Groundwater Households that are not served by public sewers Replacement Area usually depend on septic tank systems to treat and dispose of wastewater. A well-designed, installed, and maintained septic system can provide years of reliable low-cost service. When these systems fail to operate effectively, property damage, groundwater and surface water pollu- tion, and disease outbreaks can occur. Therefore, it makes good sense to understand and care for The typical septic tank is a large buried rectangu- your septic tank system. lar, or cylindrical container made of concrete, fiberglass or polyethylene. Wastewater from There are many different types of septic tank your toilet, bath, kitchen, laundry, etc., flows into systems to fit a wide range of soil and site condi- the tank. Heavy solids settle to the bottom where tions. The following information will help you bacterial action partially decomposes them to understand a conventional gravity-now septic digested sludge and gases. Most of the lighter system and keep it operating safely at the lowest solids, such as fats and grease, rise to the top and possible cost. form a scum layer. COOPERATIVE EXTENSION Tank Covers Many products on the market, such as solvents, yeast, bacteria, and enzymes claim to improve septic tank performance, or reduce the need for Liquid Level routine pumping. None of them have been found Inlet Scum Layer Outlet To to work. -

Guidance for Leachate Recirculation at Municipal Solid Waste Landfills

Guidance for Leachate Recirculation at Municipal Solid Waste Landfills Waste/Solid Waste #5.08 • June 2009 Introduction leachate generation, and thus, potential groundwater quality impacts. This Guidance has been developed to meet three goals: Of the waste in landfills at Minnesota Contents MSWLFs in 2006, approximately 77 1. Provide municipal solid waste percent went to facilities that currently Introduction ............... 1 landfill (MSWLF) owners with the have active gas collection systems History ....................... 1 minimum standards to implement Benefits ..................... 2 (Burnsville, Clay, Crow Wing, East Goals......................... 2 leachate recirculation as a tool in Central, Elk River, Pine Bend, and Spruce Design ....................... 3 managing leachate on-site and Ridge). Also in 2006, 43 percent of the Operation .................. 4 minimizing the long-term impact of waste stream went to facilities that Landfill gas the disposed waste to human health recirculate their leachate (Crow Wing, East management ............. 5 and the environment. Monitoring ................. 5 Central, Elk River, Lyon, Morrison, and Physical monitoring 2. Encourage the control of greenhouse Spruce Ridge). parameters ................ 6 Leachate monitoring gas (GHG) emissions at MSWLFs. parameters ................ 6 3. Encourage the production of energy Gas monitoring parameters ................ 7 from landfill gas as an alternative Reporting................... 8 renewable energy source. Closure...................... 9 Long-term care.......... 9 It is the intention of the Minnesota Contact information ... 9 Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) to approve leachate recirculation through permit reissuance or major permit modification at MSWLFs that meet the minimum guidelines outlined herein. This guidance supersedes any previous policy or guidance on leachate recirculation. Current MSWLF design and operation does not promote the degradation of History disposed organic wastes within a In 2006, almost 1.5 million tons of waste reasonable timeframe. -

Pesticide Waste Leachate Toxicity Evaluation and Hazard Quotient Derivation by Allium Assay

Current World Enviroment Vol. 2(2), 221-224 (2007) Pesticide waste leachate toxicity evaluation and hazard quotient derivation by Allium assay SARVESH and PRABHAKAR P. SINGH Department of Environmental Sciences, Dr. R.M.L. Avadh University, Faizabad - 2244 001 (India) (Received: November 12, 2007; Accepted: December 23, 2007) ABSTRACT This study was envisaged to explore the impact of pesticide solid waste leachate to Allium cepa (common onion) bulbs. Bulbs exposed to the leachate showed hampered root growth and morphological deformities. At 15% and higher concentrations of leachate after 5 days, gall like swellings were noticed around the mitotic zone (zone of root growth). From the dose response th th th th curve, the EC50 values for the 5 , 10 , 15 and 20 day were calculated and the highest EC50 value, th th 24.9%, was for the 5 day while the lowest EC50 value, 20%, was for the 20 day. The EC50 decreases th th th from 5 to the 20 day successively. The 5 day EC50 was used to determine the hazard quotient (HQ) of the pesticide waste leachate from the dumping site. A value of 4.49 as HQ suggests that that there is considerable risk, as any value of HQ above one (>1) is environmentally unacceptable. The response in root growth pattern, residue analysis and the HQ indicates that the leachate is toxic to rot growth of onion and steps for proper management of hazardous waste and leachate are urgently required. Keywords: Allium cepa; bioassay; pesticide waste; leachate; EC50; hazard quotient INTRODUCTION studies6,7 and risk characterization is the estimation of the incidence and severity of the effects likelihood According to a 1997 market estimate, to occur in an environmental compartment due to approximately 5684 million pounds of pesticide actual or predicted exposure to a chemical. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Science of the Total Environment. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Arp, H P., Morin, N A., Andersson, P L., Hale, S E., Wania, F. et al. (2020) The presence, emission and partitioning behavior of polychlorinated biphenyls in waste, leachate and aerosols from Norwegian waste-handling facilities Science of the Total Environment, 715: 1-12 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136824 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-169377 Science of the Total Environment 715 (2020) 136824 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv The presence, emission and partitioning behavior of polychlorinated biphenyls in waste, leachate and aerosols from Norwegian waste- handling facilities Hans Peter H. Arp a,b,⁎, Nicolas A.O. Morin a,c,PatrikL.Anderssond, Sarah E. Hale a, Frank Wania e, Knut Breivik f,g, Gijs D. Breedveld a,h a Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI), P.O. Box 3930, Ullevål Stadion, N-0806 Oslo, Norway b Department of Chemistry, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), N-7491 Trondheim, Norway c Environmental and Food Laboratory of Vendée (LEAV), Department of Chemistry, Rond-point Georges Duval CS 80802, 85021 La Roche-sur-Yon, France d Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, SE-90187 Umeå, Sweden e Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences, University of Toronto Scarborough, 1265 Military Trail, Toronto, Ontario M1C 1A4, Canada f Norwegian Institute for Air Research, P.O. -

Effectively Managing Landfill Leachate Odor Control With

Leachate Management As Seen In Effectively Managing Landfill Leachate Odor Control with Permanganate Oxidizing agents can be introduced to landfill leachate during wastewater treatment to kill the offending bacteria and reduce odor emissions to zero. Permanganate application successfully controls obnoxious odors that are released when storing and transferring landfill leachate. n By John Boll Leachate is formed when liquid passes through a landfill and odor emissions to zero. In the cases described in this article, mixes with degraded waste, picking up dissolved and suspended oxidizers such as hydrogen peroxide and chlorine were tested material. This nasty liquid contains organic and inorganic but not suitable for elimination of the offending odor. However, contaminants as well as heavy metals and pathogens. permanganate application successfully controlled obnoxious odors High levels of odor causing compounds are also found in leachate. that were released when storing and transferring landfill leachate. The primary odorant is volatile hydrogen sulfide (H2S) which When sodium permanganate is injected into leachate, in accumulates to very high levels in closed wet wells, junction boxes minutes, it reacts with dissolved hydrogen sulfide, reducing odor and pipes of collection systems. Hydrogen sulfide is generated by emissions to zero. the conversion of dissolved sulfate by anaerobic bacteria. It has an easily recognizable unpleasant, rotten egg characteristic. It Site #1 Background is detected by the human nose at very low threshold levels, but A landfill in the Northeastern U.S. operates one open cell and can also desensitize the nose after short-term exposure. Hydrogen accepts construction and demolition waste, including wall board. sulfide is a dense, heavier-than-air gas and it accumulates in Numerous neighbor complaints about odors associated with the confined spaces. -

Potential for Using Constructed Wetlands to Treat Landfill Leachate: Literature Review and Pilot Study Design

Potential for Using Constructed Wetlands to Treat Landfill Leachate: Literature Review and Pilot Study Design Sarah K. Liehr and G. Michael Sloop Department of Civil Engineering North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC 27695 Special Report Series No. 17 January 1996 The research on which this report is based was financed by the Water Resources Research Institute of The University of North Carolina. Contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Water Resources Research Institute nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute their endorsement or recommendation for use by the Institute or the State of North Carolina. WRRI Project No. 70125 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank Ray Church, Dennis Burks, Sam Hawes, Tim Heistand, and Glenn Walker of New Hanover County Environmental Management for compiling data and assisting in all aspects of construction and operation of the pilot wetland study at the New Hanover County Landfill near Wilmington, North Carolina. We would also like to thank Barbara Doll, Halford House, and Dr. Bob Rubin for their participation in planning the design for the pilot wetland study. We appreciate valuable input from Robert Mackey of Post, Buckley, Schuh & Jernigan, Inc. during the design of the pilot study. Finally, we would like to thank Jeff Masters for his input in compiling this report. ii ABSTRACf All municipal landfills are susceptible to infiltration by precipitation and runoff. As this water infiltrates the landfill, many substances leach from the fill including oxygen demanding organic compounds, suspended solids, nitrogen compounds, phosphorus, metals, and toxic organics. The composition of the leachate varies tremendously among landfills, but concentrations of several of these components may be quite high. -

Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Palm Oil Mill Effluent

processes Article Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Palm Oil Mill Effluent Tawfiq J. H. Banch 1, Marlia M. Hanafiah 1,2,*, Salem S. Abu Amr 3, Abbas F. M. Alkarkhi 3 and Mohammed Hasan 1 1 Department of Earth Sciences and Environment, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (T.J.H.B.); [email protected] (M.H.) 2 Centre for Tropical Climate Change System, Institute of Climate Change, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia 3 Universiti Kuala Lumpur Business School (Unikl bis), Kuala Lumpur 50250, Malaysia; [email protected] (S.S.A.A.); [email protected] (A.F.M.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 14 May 2020; Published: 18 May 2020 Abstract: Sanitary landfilling is the most common method of removing urban solid waste in developing countries. Landfills contain high levels of organic materials, ammonia, and heavy metals, thereby producing leachate which causes a possible future pollution of ground and surface water. Recently, agricultural waste was considered a co-substratum to promote the biodegradation of organics in industrial wastewater. The use of low-cost and natural materials for wastewater treatment is now being considered by many researchers. In this study, palm oil mill effluent (POME) was used for treating stabilized leachate from old landfill. A set of preliminary experiments using different POME/leachate ratios and aeration times was performed to identify the setting of experimental design and optimize the effect of employing POME on four responses: chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), color, and ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N). -

Microbiology of Septic Systems Microbiology of Septic Systems

Microbiology of Septic Systems Microbiology of Septic Systems The purpose of this discussion is to provide a fundamental background on the relationship between microbes, wastewater, and septic systems. • What microbes are present in septic systems? • What role do they play in the treatment process? • What concerns are associated with them? Microbiology of Septic Systems The Microbes The microbes associated with septic systems are bacteria, fungi, algae, protozoa, rotifers, and nematodes. Bacteria are by a wide margin the most numerous microbes in septic systems. Microbiology of Septic Systems Bacteria constitute a large domain of prokaryotic (single cell, no nucleus) micro- organisms. They are present in most habitats on the planet and the live bodies of plants and animals. Escherichia coli Microbiology of Septic Systems Fungi are a large group of eukaryotic (having a nucleus and organelles) organisms that includes yeasts and molds as well as mushrooms. They are classified as a kingdom separate from plants, animals, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae bacteria. Microbiology of Septic Systems Protozoa are a diverse group of unicellular eukaryotic organisms, many of which exhibit animal-like behavior, e.g., movement. Examples include ciliates, amoebae, sporozoa, and flagellates. Assorted protozoa Microbiology of Septic Systems Rotifers are a phylum of microscopic and near- microscopic pseudo- coelomate animals, common in freshwater environments throughout the world. They eat particulate organic detritus, dead bacteria, algae, and protozoans. Typical rotifer. Microbiology of Septic Systems Nematodes , or roundworms, are one of the most diverse of all animal phyla. Over 28,000 species have been described, of which over 16,000 are parasitic. The total number of species has been estimated to be about 1,000,000. -

Local Board of Health Guide to On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems

Local Board of Health Guide to On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems ©2006 National Association of Local Boards of Health 1840 East Gypsy Lane Road Bowling Green, Ohio 43402 www.nalboh.org Back Side of Cover and is Blank Local Board of Health Guide to On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems Author: Judith Simms, MS Utah State University Editors: L. Fleming Fallon Jr., MD, DrPH Director of NW Ohio Consortium for Public Health Director, Professor of Public Health Programs – Bowling Green State University Jeff Neistadt, MS, RS National Association of Local Boards of Health National Association of Local Boards of Health 1840 East Gypsy Lane Road Bowling Green, Ohio 43402 Phone: (419) 353-7714; Fax: (419) 352-6278 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.nalboh.org Additional NALBOH Materials Videotapes/Digital Media • Assurance, Policy Development, and Assessment: The Role of the Local Board of Health • The Changing Roles of Local Boards of Health: From Service Provision to Assurance – Dr. Susan Scrimshaw, 3rd Annual Ned E. Baker Lecturer • Communicating Under Fire: Focus on Public Health Situations – Dr. Vincent Covello, 4th Annual Ned E. Baker Lecturer • Local Responsibilities Related to National Environmental Health Priorities – Dr. Richard Jackson, 5th Annual Ned E. Baker Lecturer • Multiple Partnerships: Endless Opportunities – Dr. William Keck, 1st Annual Ned E. Baker Lecturer • The Role of Local Boards of Health in Promoting Food Safety • Working with Local Elected Officials to Improve Public Health - Dr. Vaughn Mamlin Upshaw, 6th Annual