Local Board of Health Guide to On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Septic Tanks, Are a Contributing Factor to Phosphorus As Well As Site Specific Conditions

Scotland’s centre of expertise for waters Practical measures for reducing phosphorus and faecal microbial loads from onsite wastewater treatment system discharges to the environment A review i Scotland’s centre of expertise for waters This document was produced by: Juliette O’Keeffe and Joseph Akunna Abertay University Bell Street, Dundee DD1 1HG and Justyna Olszewska, Alannah Bruce and Linda May Centre for Ecology & Hydrology Bush Estate Penicuik Midlothian EH26 0QB and Richard Allan Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW) The James Hutton Institute Invergowrie Dundee DD2 5DA Research Summary Key Findings Onsite wastewater treatment systems (OWTS), the majority of local flow and load characteristics of the effluents streams, which are septic tanks, are a contributing factor to phosphorus as well as site specific conditions. With that in mind, measures and faecal microbial loads. OWTS contribute to waterbodies such as awareness raising, site planning, and maintenance failing to meet Water Framework Directive (WFD) objectives are likely to contribute to reduction of impact of OWTS on and as such, measures to improve the quality of OWTS the environment. The level of load reduction possible from discharges are required. Literature has been reviewed for measures such as awareness raising is difficult to quantify, a range of measures designed to reduce phosphorus and but it is low-cost and relatively easy to implement. Those most pathogen concentrations in effluent from OWTS. A feasibility effective for phosphorus and pathogen removal are post-tank assessment focussed on their application, effectiveness, measures that maximise physical removal, through adsorption efficiency, cost and ease of adaptation. A wide range of and filtering, and maintain good conditions for biological measures have been identified that could potentially improve breakdown of solids and predation of pathogens. -

INVESTIGATION of ANAEROBIC PROCESSES in SEPTIC TANK AS a WASTEWATER TREATMENT OPTION Odenigbo C

International Journal of Civil Engineering, Construction and Estate Management Vol.6, No.1, pp.22-25, May 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) INVESTIGATION OF ANAEROBIC PROCESSES IN SEPTIC TANK AS A WASTEWATER TREATMENT OPTION Odenigbo C. Department of Civil Engineering, Enugu State University of Science and Technology ABSTRACT: This study aims to find out the anaerobic processes in septic tank as a wastewater treatment plant. Samples were collected from both a septic tank and soakaway pit. Thus, after the collection of samples from the location, waste water analysis was conducted on the two water samples A and B respectively. The results obtained on the water samples showed that sample A under physical analysis using thermometer, pH meter, conductivity meter etc, has a higher physical characteristics value according to table 4.1, than that of sample B. more also from the chemical analysis seen in table 4.1 sample A has a higher BOD, COD and DO values more than that of sample B. Therefore this suggests that biological treatment processes was efficient in that septic tank and as such waste water discharged to the environment, will be harmless to the inhabitants in that environment. KEYWORDS: Anaerobic, Septic Tank, Sewage, Treatment. INTRODUCTION Human waste or more technically referred to as Excrets, which is made up of a solid matter, faeces and liquid matter, urine and is essentially an organic compound. The constituents making up the compound are carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and hydrogen. Also present are fats, carbohydrates, enzymes, proteins, trace elements, pathogens and many different bacteria. -

Properly Managing Your Septic Tank System

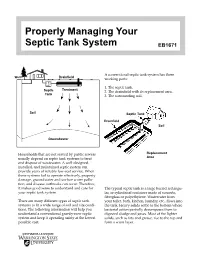

Properly Managing Your Septic Tank System EB1671 A conventional septic tank system has three Well Drainfield working parts: 1. The septic tank. Treatment Septic 2. The drainfield with its replacement area. Tank 3. The surrounding soil. Soil Septic Tank Drainfield Soil Groundwater Households that are not served by public sewers Replacement Area usually depend on septic tank systems to treat and dispose of wastewater. A well-designed, installed, and maintained septic system can provide years of reliable low-cost service. When these systems fail to operate effectively, property damage, groundwater and surface water pollu- tion, and disease outbreaks can occur. Therefore, it makes good sense to understand and care for The typical septic tank is a large buried rectangu- your septic tank system. lar, or cylindrical container made of concrete, fiberglass or polyethylene. Wastewater from There are many different types of septic tank your toilet, bath, kitchen, laundry, etc., flows into systems to fit a wide range of soil and site condi- the tank. Heavy solids settle to the bottom where tions. The following information will help you bacterial action partially decomposes them to understand a conventional gravity-now septic digested sludge and gases. Most of the lighter system and keep it operating safely at the lowest solids, such as fats and grease, rise to the top and possible cost. form a scum layer. COOPERATIVE EXTENSION Tank Covers Many products on the market, such as solvents, yeast, bacteria, and enzymes claim to improve septic tank performance, or reduce the need for Liquid Level routine pumping. None of them have been found Inlet Scum Layer Outlet To to work. -

Microbiology of Septic Systems Microbiology of Septic Systems

Microbiology of Septic Systems Microbiology of Septic Systems The purpose of this discussion is to provide a fundamental background on the relationship between microbes, wastewater, and septic systems. • What microbes are present in septic systems? • What role do they play in the treatment process? • What concerns are associated with them? Microbiology of Septic Systems The Microbes The microbes associated with septic systems are bacteria, fungi, algae, protozoa, rotifers, and nematodes. Bacteria are by a wide margin the most numerous microbes in septic systems. Microbiology of Septic Systems Bacteria constitute a large domain of prokaryotic (single cell, no nucleus) micro- organisms. They are present in most habitats on the planet and the live bodies of plants and animals. Escherichia coli Microbiology of Septic Systems Fungi are a large group of eukaryotic (having a nucleus and organelles) organisms that includes yeasts and molds as well as mushrooms. They are classified as a kingdom separate from plants, animals, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae bacteria. Microbiology of Septic Systems Protozoa are a diverse group of unicellular eukaryotic organisms, many of which exhibit animal-like behavior, e.g., movement. Examples include ciliates, amoebae, sporozoa, and flagellates. Assorted protozoa Microbiology of Septic Systems Rotifers are a phylum of microscopic and near- microscopic pseudo- coelomate animals, common in freshwater environments throughout the world. They eat particulate organic detritus, dead bacteria, algae, and protozoans. Typical rotifer. Microbiology of Septic Systems Nematodes , or roundworms, are one of the most diverse of all animal phyla. Over 28,000 species have been described, of which over 16,000 are parasitic. The total number of species has been estimated to be about 1,000,000. -

National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas (November 2005, EPA-841-B-05-004)

This PDF file is an excerpt from the EPA guidance document entitled National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas (November 2005, EPA-841-B-05-004). The full guidance can be downloaded from http://www.epa.gov/owow/nps/urbanmm/index.html. National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas Management Measure 6: New and Existing On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems November 2005 Management Measure 6: New and Existing On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems MANAGEMENT MEASURE 6 NEW AND EXISTING ON-SITE WASTEWATER TREATMENT SYSTEMS 6.1 Management Measure Develop or maintain on-site wastewater treatment system (OWTS) permitting and installation programs that adequately protect surface water and ground water quality. Programs should include: — A process to identify and protect sensitive areas (e.g., wellhead protection zones, nitrogen/phosphorus limited waters, shellfish habitat) and ensure that cumulative hydraulic discharges and mass pollutant loads from on-site systems do not impair surface or ground water; — System selection, siting, design, and installation based on performance requirements, prescriptive technologies, protective setbacks, and separation distances that protect surface water and ground water resources; — Education, training, licensing, and/or certification programs for system designers, site evaluators, permit writers, installers, inspectors, and other service providers; and — Inspections of new on-site systems during and immediately following construction/installation to ensure that design and siting criteria are applied appropriately in the field. Establish and implement management programs to ensure that newly permitted and existing on- site wastewater treatment systems are operated and maintained properly to prevent the impairment or degradation of surface and/or ground waters. -

Septic System Is Your Responsibility

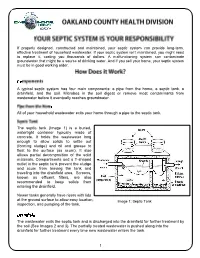

If properly designed, constructed and maintained, your septic system can provide long-term, effective treatment of household wastewater. If your septic system isn’t maintained, you might need to replace it, costing you thousands of dollars. A malfunctioning system can contaminate groundwater that might be a source of drinking water. And if you sell your home, your septic system must be in good working order. A typical septic system has four main components: a pipe from the home, a septic tank, a drainfield, and the soil. Microbes in the soil digest or remove most contaminants from wastewater before it eventually reaches groundwater. All of your household wastewater exits your home through a pipe to the septic tank. The septic tank (Image 1) is a buried, watertight container typically made of concrete. It holds the wastewater long enough to allow solids to settle out (forming sludge) and oil and grease to float to the surface (as scum). It also allows partial decomposition of the solid materials. Compartments and a T-shaped outlet in the septic tank prevent the sludge and scum from leaving the tank and traveling into the drainfield area. Screens, known as effluent filters, are also recommended to keep solids from entering the drainfield. Newer tanks generally have risers with lids at the ground surface to allow easy location, Image 1: Septic Tank inspection, and pumping of the tank. The wastewater exits the septic tank and is discharged into the drainfield for further treatment by the soil (See Images 2 and 3). The partially treated wastewater is pushed along into the drainfield for further treatment every time new wastewater enters the tank. -

(UV Leds) for Treating Wastewater and Septic Tank Effluent

water Article Woven-Fiber Microfiltration (WFMF) and Ultraviolet Light Emitting Diodes (UV LEDs) for Treating Wastewater and Septic Tank Effluent Sara E. Beck 1,2,* , Poonyanooch Suwan 1, Thusitha Rathnayeke 1, Thi Minh Hong Nguyen 1,3 , Victor A. Huanambal-Sovero 4 , Boonmee Boonyapalanant 1, Natalie M. Hull 5,6 and Thammarat Koottatep 1 1 School of Environment, Resources, and Development, Asian Institute of Technology, 58 Moo 9, Km. 42, Paholyothin Highway, Khlong Luang, Pathum Thani 12120, Thailand; [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (T.M.H.N.); [email protected] (B.B.); [email protected] (T.K.) 2 Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3 QAEHS—Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4102, Australia 4 Departamento de Ingeniería, Facultad de Ciencias y Filosofía, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima 15102, Peru; [email protected] 5 Department of Civil, Environmental, and Geodetic Engineering, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; [email protected] 6 Sustainability Institute, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Beck, S.E.; Suwan, P.; Rathnayeke, T.; Nguyen, T.M.H.; Abstract: Decentralized wastewater treatment systems enable wastewater to be treated at the source Huanambal-Sovero, V.A.; Boonyapalanant, B.; Hull, N.M.; for cleaner discharge into the environment, protecting public health while allowing for reuse for Koottatep, T. Woven-Fiber agricultural and other purposes. This study, conducted in Thailand, investigated a decentralized Microfiltration (WFMF) and wastewater treatment system incorporating a physical and photochemical process. -

A Homeowner's Guide to Septic Tank Effluent Pumping (STEP) Systems

A Homeowner’s Guide to Septic Tank Effluent Pumping (STEP) Systems Clark Regional Wastewater District is providing this manual to help you become more familiar with your STEP sewer system. Your STEP System is our responsibility Top four ways to protect STEP stands for Septic Tank Effluent Pumping. The STEP system on your property is actually owned by your STEP system: Clark Regional Wastewater District. An easement 1. DO call the District at (360) is in place that allows the District access to perform 750-5876 if you hear or maintenance and repairs of the STEP system. The see the alarm go off. District will always try to notify property owners 2. DO let CRWWD before conducting any work. personnel repair and maintain the system. How does a STEP System work? Don’t try to do it yourself. The STEP System includes a septic tank and a 3. DON’T use your system pump. Sewage is conveyed by gravity to the tank for garbage. through your building plumbing line. Liquid waste is 4. DON’T dispose of toxic or pumped under pressure to the public sewer system. flammable material into Solid waste will remain in the STEP tank where your system. it naturally degrades and is eventually pumped out. STEP system pumps typically turn on every one or two days with normal water use. Clark Regional Wastewater District Service Panel & Sewer Line maintenance personnel will inspect your Alarm Light tank at least every 5 years and will pump out the solids every 10 years if needed. Pump / Access Cover If you suspect that your tank may need maintenance, please give us a call. -

Septic System Impacts on Groundwater Quality William Robertson

Title Author(s) 1 Septic System Impacts on Groundwater Quality William Robertson i The GROUNDWATER PROJECT ©The Author Free download from gw-project.org Anyone may use and share gw-project.org links. Direct distribution of the book is strictly prohibited. Septic System Impacts on Groundwater Quality William Robertson ii The GROUNDWATER PROJECT ©The Author Free download from gw-project.org Anyone may use and share gw-project.org links. Direct distribution of the book is strictly prohibited. Septic System Impacts on Groundwater Quality William Robertson All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the authors (to request permission contact: [email protected]). Commercial distribution and reproduction are strictly prohibited. GW-Project works can be downloaded for free from gw-project.org. Anyone may use and share gw-project.org links to download GW-Project’s work. It is not permissible to make GW-Project documents available on other websites nor to send copies of the documents directly to others. Copyright © 2021 William Robertson (The Author) Published by the Groundwater Project, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 2020. Robertson, William Septic System Impacts on Groundwater Quality / William Robertson - Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 2021. 38 p. ISBN: 978-1-77470-004-4 Please consider signing up to the GW-Project mailing list and stay informed about new book releases, events and ways to participate in the GW-Project. When you sign up to our email list it helps us build a global groundwater community. -

Septic Management – Part of Your HAB Prevention Tool Box Thanks To

Septic Management – Part of Your HAB Prevention Tool Box Thanks To CWC No, Not Another HAB Alert!!! Harmful algal blooms are back in N.J. - HABs have sprung up in waterbodies across New Jersey, compelling state officials to issue warnings to visitors to exercise caution at certain recreational areas… Excerpt from - Caroline Fassett | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, 9 June 2021. CWC What Triggers A HAB? Typical conditions that favor onset of a bloom: • Warm water temperatures. • Plenty of sunlight for photosynthesis. • Relatively stable water column. • Quick influx of phosphorus...may originate from internal and/or external sources. CWC The Phosphorus Connection Phosphorus (P) is key nutrient driving aquatic productivity and HABs. More phosphorus = More cyanobacteria = HAB HAB management starts with knowing phosphorus sources and how much phosphorus associated with each source (internal and external). CWC If Phosphorus Is The Problem... What Can I Do About It? CWC Phosphorus Sources External Internal Atmospheric CWC Vary in Magnitude, Importance and Seasonality • Internal (In-lake) • Sediment release and recycling • Decomposition of organic material (algae, weeds, fish, etc.) • External (watershed) • Stormwater runoff (direct and indirect) • Septic systems • Point sources • Atmospheric • Waterfowl CWC Phosphorus, Eutrophication and HABs Lakes need to be on a phosphorus diet to avoid or mitigate a HAB Septic systems are phosphorus sources 9 CWC HAB Management Options • Root Cause Management Measures… Actions to decrease phosphorus loading, alter lake environment to prevent a HAB. • Proactive Mitigation Measures… Actions to lessen the severity of a developing HAB. • Reactive Measures…Actions to lessen the severity or duration of an existing HAB. CWC Root Cause Management Source Control Actions … • Septic care and management • Non-phosphorus fertilizers • Green infrastructure…decrease runoff • Waterfowl control • Soil erosion control CWC Septic Systems and Lake Communities • As per USEPA…> 20% of homes in US depend on septic systems to treat wastewater. -

Domestic Wells Have High Probability of Pumping Septic Tank Leachate

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 2453–2467, 2012 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/16/2453/2012/ Hydrology and doi:10.5194/hess-16-2453-2012 Earth System © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Sciences Domestic wells have high probability of pumping septic tank leachate J. E. Bremer1,* and T. Harter1 1Department of Land, Air, and Water Resources, University of California, Davis, CA 95616-8629, USA *now at: Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Kaiserstr. 12, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany Correspondence to: T. Harter ([email protected]) Received: 16 May 2011 – Published in Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 15 June 2011 Revised: 14 June 2012 – Accepted: 28 June 2012 – Published: 3 August 2012 Abstract. Onsite wastewater treatment systems are common 1 Introduction in rural and semi-rural areas around the world; in the US, about 25–30 % of households are served by a septic (onsite) wastewater treatment system, and many property owners also In rural, semi-rural, and many suburban areas, septic systems operate their own domestic well nearby. Site-specific con- (onsite wastewater treatment systems, OWTS) are the pri- ditions and local groundwater flow are often ignored when mary method for wastewater disposal. In the US, about one installing septic systems and wells. In areas with small lots in four households operates a septic system and almost one- (thus high spatial septic system densities), shallow domestic third of new homes are constructed with an OWTS as their wells are prone to contamination by septic system leachate. wastewater disposal system (US EPA, 2003a; US DC, 2008). -

Sediment Stress, Water Turbidity, and Sewage Impacts on Threatened Elkhorn Coral (Acropora Palmata) Stands at Vega Baja, Puerto Rico

Sediment stress, water turbidity and sewage impacts on threatened Elkhorn Coral (Acropora palmata) Stands at Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. Item Type conference_item Authors Hernandez-Delgado, E.; Hutchinson-Delgado, Y.M.; Laureano, R.; Hernández-Pacheco, R.; Ruiz-Maldonado, T.M.; Ohms, J.; Díaz, P.L. Download date 26/09/2021 22:44:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31337 Sediment Stress, Water Turbidity, and Sewage Impacts on Threatened Elkhorn Coral (Acropora palmata) Stands at Vega Baja, Puerto Rico EDWIN A. HERNÁNDEZ-DELGADO1*, YAHAIRA M. HUTCHINSON-DELGADO2, RICARDO LAUREANO3, RAISA HERNÁNDEZ-PACHECO1, TAGRID M. RUIZ-MALDONADO1, JULIO OMS4, and PEDRO L. DÍAZ4 1University of Puerto Rico, Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation, Coral Reef Research Group, PO Box 23360, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931-3360. 2University of Puerto Rico, Department of Marine Sciences, Call Box 9000, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico 00681-9000. 3Vegabajeños Impulsando Desarrollo Ambiental Sustentable (VIDAS), Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, 4U.S. Geological Survey, GSA Center, 651 Federal Drive, Suite 400-15, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico 00965-5703. *[email protected]. ABSTRACT Poorly implemented beach renourishment activities and increasing raw sewage pollution from local storm sewers and other non-point sources have significantly impacted coral reef communities at the candidate Vega Baja Submarine Gardens Natural Reserve, Puerto Rico. There have been recurrent violations to legal water turbidity and microbiological water quality standards. Percent living cover of threatened Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) across six reefs declined by 29% within 1997 and 2008, for an annual mean loss of 2.65%. But mortality rocketed to 52% between December 2008 and June 2009 across the zone following beach renourishment and recurrent raw sewage spills.