Annabel Scheme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

Feeling Black & Blue

DEBORAH KASS: FEELING BLACK & BLUE Deborah Kass and I were assembling a small mountain of discarded pistachio shells while sipping a stiff pour-over and peering at new works for her upcoming show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, which opens at the end of this year. They were works in progress, a cluster of leaning blue and black mixed-medium canvases that were nearly the height of the ceiling and dominated the space. I asked her if a sleek black multipaneled piece commandeering the better part of the back wall in her studio was intended to be reflective. “Oh, yeah,” she said. Her new series feels invariably necessary to the larger body of her work, perhaps inevitable. Why black and blue? “It’s how I feel,” she sighed. And Kass was making similar pieces even before she began the series. Miniature prototypes from years before littered random crannies of her studio—small blueprints of the evolution of these works. They’re a natural continuation of “Feel Good Paintings for Feel Bad Times” (2007–10), an extension of both her identity as an artist and her exceptional command of art history. Following a conversation with Whitewall late last year, we talked briefly about her May show at Sargent’s Daughters in New York, her Warholian “America’s Most Wanted” series (1998–99). The amount of work she erected in the month between our visits was astonishing, which she chalked up to part realized aesthetic trajectory, part prolonged absence from her studio while her building was being remodeled. Sitting down with Whitewall for the first unveiling of her new series, Kass spoke with us about multiculturalism, feminism, and as always, her love of pop culture. -

Linn Lounge Presents... the Rolling Stones

Linn Lounge Presents... The Rolling Stones Welcome to Linn Lounge presents… ‘The Rolling Stones’ Tonight’s album, ‘Grr’ tells the fascinating ongoing story of the Greatest Rock'n'Roll Band In The World. It features re-masters of some of the ‘Stones’ iconic recordings. It also contains 2 brand new tracks which constitute the first time Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood have all been together in the recording studio since 2005. This album will be played in Studio Master - the highest quality download available anywhere, letting you hear the recording exactly as it left the studio. So sit back, relax and enjoy as you embark on a voyage through tonight’s musical journey. MUSIC – Muddy Waters, Rollin’ Stone via Spotify (Play 30secs then turn down) It all started with Muddy Waters. A chance meeting between 2 old friends at Dartford railway station marked the beginning of 50 years of rock and roll. In the early 1950s, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger were childhood friends and classmates at Wentworth Primary School in Kent until their families moved apart.[8] In 1960, the pair met again on their way to college at Dartford railway station. The Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters records that Jagger carried revealed a mutual interest. They began forming a band with Dick Taylor and Brian Jones from Blues Incorporated. This band also contained two other future members of the Rolling Stones: Ian Stewart and Charlie Watts.[11] So how did the name come about? Well according to Richards, Jones christened the band during a phone call to Jazz News. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

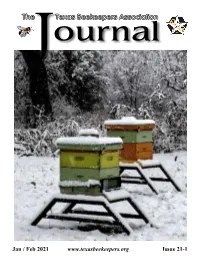

Jan / Feb 2021 Issue 21-1

The Texas Beekeepers Association Journal Jan / Feb 2021 www.texasbeekeepers.org Issue 21-1 2 THE JOURNAL OF THE TEXAS BEEKEEPERS ASSOCIATION Issue 21-1 President’s Report from Ashley Ralph Wow, it’s 2021! This may be a short article for me as we work Stillman, Charlie Agar, Chris Moore, Dennis Herbert and Leesa to finish preparing our bees for their annual trip to California. It’s Hyder) has been diligently covering the 87th Texas Legislature a busy and exciting time of year. Our bees are bringing in a ton since opening day on January 12. Consistent with Resolutions of pollen which means queen rearing and splits season is right passed by the TBA membership at our last annual meeting around the corner. in November 2019, we will be closely watching for proposed Our TBA Board has a new member! Roger Farr stepped down legislation that may affect Chapter 131 of the Texas Agriculture after his second productive term and we’re so grateful for his Code and apiary regulations, the beekeeping qualification for contributions to building systems for TBA and THBEA. Rebecca agricultural valuation, the management of roadside and public Vaughan has graciously agreed to accept an appointment to this land for valuable bee forage, the honest and ethical marketing of position, she has done an amazing job working on our events real Texas honey and the general interests of all scales of Texas for the past 2 years and we’re so excited she has joined our TBA beekeepers. Board. We’re prepared to take appropriate action consistent with We also have some exciting new members to the Texas Honey the membership resolutions and TBA’s mission. -

Emotional Rescue This Was Not an Album Cover That People Loved. Fan

Emotional Rescue This was not an album cover that people loved. Fan reaction was typified by comments like, “this messy cover,” “It may have the single ugliest cover artwork of any record ever released by a major rock artist,” “I still hate the album cover,” “It's butt-ugly,” “I hate the cover,” “The cover is a big part of its poor reception.” “The sleeve was a big let-down after Some Girls, also the waste of time poster included,” “Yeah, I hated the cover…I like covers that show the band...like Black and Blue,” “I can't defend the thermal photography, or whatever it is, that adorns the cover of Emotional Rescue - was Mick on heroin when he signed off on this concept?” "Everyone to his own taste," the old woman said when she kissed her cow. It seems the Stones may have kissed a cow on this album cover. The Title You can always name it after a song on the album. That worked for Let It Bleed, It’s Only Rock and Roll and Some Girls. There were a lot of songs left over from the Some Girls sessions so this album began life with cynical working titles like Certain Women a clear play on the Some Girls title and More Fast Ones an obvious allusion to the pace of the contents. As the album began to take shape it took on the working title of Saturday Where The Boys Meet, a bit of a theme from the song “Where the Boys Go,” which appeared on the album. -

Albums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts the Rolling Stones

Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling Stones 1 2 3 4 04/1964 3 1 12 11 11/1964 3 12/1964 4 01/1965 1 3101 The Rolling Stones (England's 12 X 5 Around And Around Rolling Stones No. 2 Newest Hit Makers) 5 6 7 8 04/1965 5 08/1965 2 2 1 3 11/1965 1 4 12/1965 4 The Rolling Stones, Now! Out Of Our Heads Bravo Rolling Stones December's Children (And Everybody's) 9 10 11 12 04/1966 1 881 2 04/1966 4 3 01/1967 6 01/1967 2 Aftermath Big Hits (High Tide And Green Got Live If You Want It The Rolling Stones Live Grass) 13 14 15 16 01/1967 2 3 2 08/1967 7 3 12/1967 4 3 2 12/1968 8 3 5 Between The Buttons Flowers Their Satanic Majesties Request Beggars Banquet Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling Stones 17 18 19 20 09/1969 13 2 2 12/1969 3 1 1 3 09/1970 6 1 2 6 04/1971 30 4 Through The Past Darkly (Big Let It Bleed Get Yer Ya‐Ya's Out! Stone Age Hits Vol. 2) 21 22 23 24 04/1971 1 351 1 409/1971 19 01/1972 3 4 03/1972 14 Sticky Fingers Gimme Shelter Hot Rocks 1964 ‐ 1971 Milestones 25 26 27 28 05/1972 2 1 241 11/1972 41 01/1973 9 09/1973 2 1 241 Exile On Main Street Rock'n'Rolling Stones More Hot Rocks (Big Hits & Goat's Head Soup Fazed Cookies) 29 30 31 32 10/1974 12 2 1 1 06/1975 45 8 06/1975 14 6 12/1975 7 It's Only Rock'n'roll Metamorphosis Made In The Shade Rolled Gold ‐ The Very Best Of The Rolling Stones Month of 1st Entry Peak+wks # 1: DE GB USAlbums‐ Chart‐History Regarding Albums Top 50 ‐ Charts The Rolling -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Berköz, Levent Donat (2012). A gendered musicological study of the work of four leading female singer-songwriters: Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush, and Tori Amos. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1235/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Gendered Musicological Study of the Work of Four Leading Female Singer-Songwriters: Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush, and Tori Amos Levent Donat Berköz Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy City University London Centre for Music Studies June 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ………………………………………………………… 2 LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………… 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………… 7 DECLARATION ………………………………………………………………… 9 ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………… 10 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….. 11 Aim of the thesis…………………………………………………………………. -

Made in the Shade the Begats Andrew Loog Oldham Begat Necrophilia

Metamorphosis and Made In The Shade The Begats Andrew Loog Oldham begat Necrophilia. Allen Klein begat More Hot Rocks (Big Hits and Fazed Cookies) which vanquished Necrophilia. Bill Wyman begat Black Box. Allen Klein begat Metamorphosis, which vanquished Black Box. The Rolling Stones begat Made In The Shade. Necrophilia Metamorphosis is the album the Rolling Stones had nothing to do with and did not want to see released, it was also the culmination of a 3-year effort by the Stones to produce just such a compilation that began with Necrophilia. Hot Rocks 1964–1971 was a compilation album that had been released December 20, 1971 by London Records. It is also the best-selling release of the Stones’ career. In 1972, Andrew Loog Oldham, the Stones original manager, began compiling an album for release as the follow-up to Hot Rocks. It was entitled Necrophilia and it featured previously unreleased or, more accurately, discarded outtakes from the Stones' Decca/London period. Designed by Fabio Nicoli as a tri- gatefold album it used photos from Gered Menkowitz’s Between the Buttons photoshoot for the outer cover. The inside of the unreleased Necrophilia was recycled and used for the cover of More Hot Rocks (Big Hits and Fazed Cookies) in December 1972. 1. Out of Time* A very limited number of copies of Necrophilia had 2. Don’t Lie to Me* been produced when, popular mythology has it, a 3. Have You Seen Your Mother major disagreement arose between Oldham and Baby, Standing in the Shadow Stones’ Manager Allen Klein. The playlist of Necrophilia 4. -

Bee Friendly: a Planting Guide for European Honeybees and Australian Native Pollinators

Bee Friendly A planting guide for European honeybees and Australian native pollinators by Mark Leech From the backyard to the farm, the time to plant is now! Front and back cover photo: honeybee foraging on zinnia Photo: Kathy Keatley Garvey Bee Friendly A planting guide for European honeybees and Australian native pollinators by Mark Leech i Acacia acuminata © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation All rights reserved. ISBN 978 1 74254 369 7 ISSN 1440-6845 Bee Friendly: a planting guide for European honeybees and Australian native pollinators Publication no. 12/014 Project no. PRJ-005179 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication.