ABSTRACT Title of Document: HISTORY LIMITED: the HIDDEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academy of Television Arts & Sciences 64Th Primetime Emmy

Academy of Television Arts & Sciences 64th Primetime Emmy Award Nominations Nominations for this year’s Primetime Emmys were announced by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, Thursday, July 19, 2012. The Primetime Emmy Awards will be televised September 23, 2012. Below is a listing of the shows nominated this year for Art Direction. Outstanding Art Direction For A Multi-Camera Series Hell's Kitchen • Episode 915 • Episode 916 • FOX • ITV Studios America in association with A. Smith & Co. John Janavs, Production Designer Robert Frye, Art Director Heidi Miller, Set Decorator How I Met Your Mother • Now We're Even • The Magician's Code, Part One • The Magician's Code, Part Two • CBS • 20 th Century Fox Television Stephan G. Olson, Production Designer Susan Eschelbach, Set Decorator Mike & Molly • Goin' Fishin' • Valentine's Piggyback • The Wedding • CBS • Bonanza Productions, Inc. in association with Chuck Lorre Productions, Inc. and Warner Bros. Television John S. Shaffner, Production Designer Lynda Burbank, Set Decorator 30 Rock • Live From Studio 6H • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television Teresa Masterpierro, Production Designer Keith Raywood, Production Designer Jennifer Greenberg, Set Decorator 2 Broke Girls • And The Rich People Problems • And The Reality Check • And The Pop Up Sale • CBS • Bonanza Productions, Inc. in association with MPK Productions and Warner Bros. Television Glenda Rovello, Production Designer Amy Feldman, Set Decorator Outstanding Art Direction For A Single-Camera -

Eugene Du Pont Jr. Papers 2656

Eugene du Pont Jr. papers 2656 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Eugene du Pont Jr. papers 2656 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

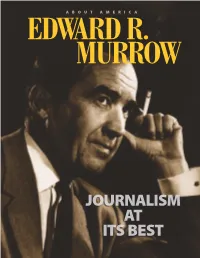

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

Edward R. Murrow

Edward R. Murrow Edward Roscoe Murrow (April 25, 1908 – April 27, 1965), born Egbert Roscoe Murrow,[1] was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained Edward R. Murrow prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broadcasts from Europe for the news division of CBS. During the war he recruited and worked closely with a team of war correspondents who came to be known as the Murrow Boys. A pioneer of radio and television news broadcasting, Murrow produced a series of reports on his television program See It Now which helped lead to the censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Fellow journalists Eric Sevareid, Ed Bliss, Bill Downs, Dan Rather, and Alexander Kendrick consider Murrow one of journalism's greatest figures, noting his honesty and integrity in delivering the news. Contents Early life Career at CBS Radio Murrow in 1961 World War II Born Egbert Postwar broadcasting career Radio Roscoe Television and films Murrow Criticism of McCarthyism April 25, Later television career Fall from favor 1908 Summary of television work Guilford United States Information Agency (USIA) Director County, North Death Carolina, Honors U.S. Legacy Works Died April 27, Filmography 1965 Books (aged 57) References Pawling, New External links and references Biographies and articles York, U.S. Programs Resting Glen Arden place Farm Early life 41°34′15.7″N 73°36′33.6″W Murrow was born Egbert Roscoe Murrow at Polecat Creek, near Greensboro,[2] in Guilford County, North Carolina, the son of Roscoe Conklin Murrow and Ethel F. (née Lamb) Alma mater Washington [3] Murrow. -

The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary

Media History Monographs 12:1 (2010) ISSN 1940-8862 The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary By Lawrence N. Strout Mississippi State University Three major TV and film productions about Edward R. Murrow‟s life are the subject of this research: Murrow, HBO, 1986; Edward R. Murrow: This Reporter, PBS, 1990; and Good Night, and Good Luck, Warner Brothers, 2005. Murrow has frequently been referred to as the “father” of broadcast journalism. So, studying the “documentation” of his life in an attempt to ascertain its historical role in supporting, challenging, and/or adding to the collective memory and mythology surrounding him is important. Research on the docudramas and documentary suggests the depiction that provided the least amount of context regarding Murrow‟s life (Good Night) may be the most available for viewing (DVD). Therefore, Good Night might ultimately contribute to this generation (and the next) having a more narrow and skewed memory of Murrow. And, Good Night even seems to add (if that is possible) to Murrow‟s already “larger than life” mythological image. ©2010 Lawrence N. Strout Media History Monographs 12:1 Strout: Edward R. Murrow The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary Edward R. Murrow officially resigned from Life and Legacy of Edward R. Murrow” at CBS in January of 1961 and he died of cancer AEJMC‟s annual convention in August 2008, April 27, 1965.1 Unquestionably, Murrow journalists and academicians devoted a great contributed greatly to broadcast journalism‟s deal of time revisiting Edward R. Murrow‟s development; achieved unprecedented fame in contributions to broadcast journalism‟s the United States during his career at CBS;2 history. -

Forecast Log

Forecast Log http://www.old-time.com/otrlogs2/forecast_mg.html FORECAST Is There a Sponsor in the House? Written by Martin Grams, Jr. The trial-and-error system being an old if frequently painful institution in the show business (else all stage plays would be hits, and all radio programs would have an Amos and Andy average in the Crossley ratings), the Columbia Broadcasting System’s Forecast series shrewdly dramatized the fact that there is no such phenomenon as a sure thing. For two particular seasons, the CBS people enlivened summer’s somewhat lethargic air waves with a schedule of experimental entertainments which, to tell the truth, aren’t experimental in the exact sense of the word, but have nevertheless a refreshing air about them, if only for the ideas they represented. The idea is that neither CBS nor anyone else knew, until they were produced, whether the programs were any good or not, though they were of course, hoping for the best. And, very sensibly, they made a game of it. Whereas the listener during the busy season was told to take what he got and, if possible, like it, Forecast invited criticism. Listening to the various episodes, one could not help but applaud for Marlene Dietrich in "The Thousand and One Nights," and convulsed with laughter as they listened to the amorous antics of "Mischa the Magnificent." (Mischa Auer, that is.) Whatever it was that made people bet on horse races or write letters to the editor, they could file an honest opinion about the programs and then sat back to await the verdict. -

Give My Regards to Market Street Theaters As A

GIVE MY REGARDS TO MARKET STREET THEATERS AS A REPRESENTATION OF URBAN GROWTH IN WILMINGTON, DELAWARE, 1870-1930 by Courtney Lynahan A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Urban Affairs and Public Policy Summer 2010 2010 Courtney Lynahan All Rights Reserved GIVE MY REGARDS TO MARKET STREET THEATERS AS A REPRESENTATION OF URBAN GROWTH IN WILMINGTON, DELAWARE, 1870-1930 by Courtney Lynahan Approved: __________________________________________________________ Rebecca Sheppard, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Maria P. Aristigueta, D.P.A. Director of the School of Urban Affairs and Public Policy Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the College Education and Public Policy Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This list has grown exponentially over the years, so here goes. First and foremost to Becky for her guidance and patience. Thank you. My committee members David Ames and Debbie Martin. The students and staff at CHAD and at SUAPP, especially Linda for helping me with every crisis that came along and Laura for keeping me going at the end. My sister and brother in law for agreeing to read the drafts of this thesis. My Aunt Carol for being my copy editor. The amazing people at Hagley, the state archives, and my three theaters, The Grand Opera House, The DuPont Theater and The Queen for helping me, often time with no notice. To my amazing friends, particularly Alexandra, Shanna, Megan, Felicity, Steve, Colin, Annie, Anna and Sydney for listening patiently while I bounced ideas off them and especially Nicole for driving me around Wilmington and for calling me to make sure I really was writing. -

THE PRESS Friday, December 13, 1963 TELEVISION LOG for the WEEK FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY

A-8—THE PRESS Friday, December 13, 1963 TELEVISION LOG FOR THE WEEK FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY. MONDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY DECEMBER 16 DECEMBER 13 DECEMBER 14 DECEMBER 15 DECEMBER 18 DECEMBER 19 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 11:00 ( 7) AFL Game 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien ( 4) People Will Talk 11:00 ( 2) NFL Game ( 4) People Will Talk 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien 12:00 ( 2) Burns and Alien ( 5) Dateline Europe 12:00 ( 2) Sky KKing 12:00 ( 2) Insight ( 5) Cross Current ( 4) People Will Talk ( 4) People Will Talk ( 7) Tennessee ^rme ( 4) Exploring ( 4) Jr. Rose bowl ( 7) Tennessee Ernie ( 5) Overseas Adventure ( 5) Overseas Adventure ( 9) Hour of St. Francis ( 9) Searchlight on ( "<) Ernie Ford (11) Sheriff John (13) Cartoons ( 7) Press Conference Delinquency ( 7) Tennessee Ernie 9) Books and Ideaa (13) Oral Roberts ( 9) Dr. Spock 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 12:30 ( 2) Do You Know (11) Sheriff John (11) Sheriff John ( 5) TV Bingo (13) Movie (11) Sheriff John (13) Movie ( 7) Father Knows Best ( 5) Movie 12:30 ( 5) Movie ( 9) Mr. D.A. "Tonight We Raid Calali" 12:30 ( 2) As World Turn* (13) Movie 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 1:00 (2) News Lee J. Cohb (4 ) The Doctors ( 4) The Doctors 12:45 ( 5) Dateline Europe ( 7) Discovery 12:30 ( 2) As World Turns 1:00 ( 2) Password ( 4) Ornamental World ( 5) TV Bingo ( 5) TV Bingo (13) Social Security ( 7) Father Knows Best (4 ) The Doctors ( 7) Father Knows Best ( 4) Loretta Young ( 5) Movie ( 5) TV Bingo ( 5) Douglas Fairbanks ( 9) Mr. -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Edward R. Murrow: Journalism at Its Best

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life .............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S. ....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism ....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy...........................................................................16 Bibliography ..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. Front cover: © CBS News Archive 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. Tufts University. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. bot tom, AP/ W WP. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. Back cover: Edward Murrow © 1994 United States 5: left, North Wind Picture Archives; Postal Service. All Rights Reserved. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. Used with Permission. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Executive Editor: George Clack and Archives, Tufts University. Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 11: left, Library of American -

Cheat Sheet to Westeros and Beyond, Your Guide on Catching up to “Game of Thrones” Before Season 8 Starts April 14

“Game of Thrones” has several great battle scenes, and the sixth season features the Battle of the Bastards, one of the most epic battle scenes ever filmed, movie or television. COURTESY/HBO ith the final season of “Game of Thrones” fast approaching, you might feel a little left out of the pop culture phenomenon as ‘GAME OF your friends and family discuss Targaryens, Starks and Lan- nisters. But it’s not too late to get caught up, if you’re willing to Wtake a crash course in the Seven Realms. THRONES’ Today we’re giving you a cheat sheet to Westeros and beyond, your guide on catching up to “Game of Thrones” before Season 8 starts April 14. This is by no means complete. We definitely recommend you take time later to go back and watch the entire series, which is epic in scale and qual- TV ity. We’ve boiled the show’s 67 episodes down to 28, or a little over 26 hours ‘Game of CHEAT Thrones’ season of viewing. While you won’t get every detail, this list will give you what you 8 premiere need to understand the major plot points. With a bit of dedication, you can 8 p.m. April 14, HBO get through it all in a week. SHEET And if you’re already familiar with Game of Thrones, you can use this as a guide to re-familiarize yourself with the world you’ve been missing for the last 18 months. Your guide to catching up on the Seven Tip: Wikipedia has pretty good summaries for each episode. -

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives Pat O’Reilly Collection Pat O'Reilly (Daniel Patrick O'Reilly) was a news commentator and news writer for KNX and other news services from the 1940s to 1970s. He won several awards for The Big News, the first daily hour-long news telecast that began in 1961 at KNXT, and various news specials and documentaries. Box 1 Folder 1 Script: 02-11-1954 A Cell in the Country Folder 2 CD: Transcription of A Cell in the Country as broadcast on KABC. Four transcription disks with the original audio are stored separately. Folder 3 Photograph: Digital copy of photograph with Chet Huntley, Pat O’Reilly and other newsmen. Includes biography of O’Reilly. Folder 4 Photographs: (17) 00/00/1945 Men working in newsroom – identified in email from Jack Beck. 00/00/1946 Newsmen at party – identified in email from Jack Beck. 00/00/196? Newsmen at party – Pat O’Reilly, Joe Quinn, unidentified 00/00/196? Newsmen at party –Joe Quinn, unidentified, Pat O’Reilly 00/00/196? Newsmen at party – Pat O’Reilly, Joe Quinn (back to camera), unidentified 00/00/196? Pat O’Reilly, Sam Zelman (KNXT), unknown 00/00/196? Pat O’Reilly, Hub Keavy 00/00/195? Pat O’Reilly, Jack Beck, Wallace Sterling, Don Thornburg, Chester Collingwood, Harry Witt, Chet Huntley, Charles Morin, Pete Pringle, Harry Flannery, others unidentified. Seated at dinner. 00/00/196? Portrait of Pat O’Reilly. 269.tif noted on back. 12/01/1970 Pat O’Reilly and Linda Williams, with letter from Forrest Mulvane.