Fractious Memories in Medoruma Shun's Tales of War 目取真 俊の戦争作品におけるまつろわぬ記憶

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KADENA ITT LOCAL TOURS Yen for Purchases and Comfortable Walking Shoes

Whale Watching Tour is an award winning nutrient rich salt used for numerous also a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2000. It used Mini-mini Zoo Looking for adventure on the high seas? Whales are one of applications. Fees are included in the tour price but please to entertain envoys from the emperor or China during Take a short morning trip with the little ones and visit the most magnificent wonders and largest creatures in the don’t forget to bring yen for lunch and purchases. the Ryukyu Kingdom era. Entrance fees are included but the Mini Mini Zoo in Uruma City where over 40 different ocean. Once a year the whales travel to the warm waters off 16 Mar • 9 am – 3:30 pm please bring yen for lunch at Jusco and comfortable shoes. animals reside. We will also visit the on-site bakery of Okinawa to mate. Join us on this half day adventure to Don’t forget your camera. where they utilize their very own fresh eggs to produce search for and view these beautiful mammals. Please don’t Higashi Village Azalea Festival 25 Mar • 9 am – 3 pm very delicious Uruma City famous pastries. Please bring forget to bring sunscreen, a raincoat, camera, Dramamine, Catch the Azalea’s in full bloom at the biggest event in camera and yen for purchases. Tour guide not included. water and snacks. For safety reasons children must be at Higashi Village. We will celebrate this popular festival held Northern Battle Sites 3 Apr • 9:30 am – 11:30 am least 4 yrs old to board the boat. -

2020 Cherry Blossoms° Grand Okinawa Plus Snow

ate n Off the Be n Path: A Different Side of Japa ° COMPLETE 2020 CHERRY BLOSSOMS PACKAGES! GRAND OKINAWA $ * PLUS SNOW MONKEYS & TOKYO SHOPPING 4388 INCLUDES ROUNDTRIP AIRFARE FROM Very Unique Tour Itinerary! HONOLULU, 9 NIGHTS HOTEL, 18 MEALS, Let’s explore two diverse climates and cultures in one exciting trip! TIPS FOR LOCAL TOUR GUIDES AND BUS DRIVERS, ALL TAXES & FEES 9 Nights / 11 Days • 18 Meals (9 Breakfasts, 5 Lunches & 4 Dinners) Escorted from Honolulu • English-Speaking Local Guide EARLY BOOKING January 28 – February 07, 2020 • Tour Managers: Delbert & Gale Nakaoka DISCOUNT PER PERSON $ OVERVIEW: SAVE 100 BOOK BY JULY 15, 2019† Okinawa is home to a unique culture that differs considerably from that of mainland Japan. Until the islands were invaded by the Satsuma domain (present day Kagoshima Prefecture) in 1609, Okinawa existed as an entirely separate country from Japan, known as the Ryukyu Kingdom. After the invasion, SAVE $75 the Ryukyu Kingdom served as a tributary state to Japan, but continued to be governed by the royal BOOK BY AUGUST 31, 2019† family from Shuri Castle. It was not until 1879, a few years after the Meiji Restoration, that the kingdom was abolished and incorporated into Japan as Okinawa Prefecture. The castles of Okinawa, known as $ “gusuku” in the Okinawan language, are among the most vivid monuments that testify to the unique SAVE 50 BOOK BY SEPTEMBER 30, 2019† cultural and historical heritage of the Ryukyu Kingdom. In the year 2000, five castles and four related sites were designated as UNESCO World -

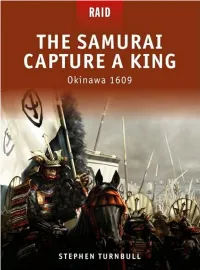

Raid 06, the Samurai Capture a King

THE SAMURAI CAPTURE A KING Okinawa 1609 STEPHEN TURNBULL First published in 2009 by Osprey Publishing THE WOODLAND TRUST Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Osprey Publishing are supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading E-mail: [email protected] woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. © 2009 Osprey Publishing Limited ARTIST’S NOTE All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, colour plates of the figures, the ships and the battlescene in this book Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, addressed to: photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Scorpio Gallery, PO Box 475, Hailsham, East Sussex, BN27 2SL, UK Print ISBN: 978 1 84603 442 8 The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 84908 131 3 this matter. Page layout by: Bounford.com, Cambridge, UK Index by Peter Finn AUTHOR’S DEDICATION Typeset in Sabon Maps by Bounford.com To my two good friends and fellow scholars, Anthony Jenkins and Till Originated by PPS Grasmere Ltd, Leeds, UK Weber, without whose knowledge and support this book could not have Printed in China through Worldprint been written. -

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan by Sumi Cho A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jennifer E. Robertson, Chair Professor Kelly Askew Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Markus Nornes © Sumi Cho All rights reserved 2014 For My Family ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Jennifer Robertson for her guidance, patience, and feedback throughout my long years as a PhD student. Her firm but caring guidance led me through hard times, and made this project see its completion. Her knowledge, professionalism, devotion, and insights have always been inspirations for me, which I hope I can emulate in my own work and teaching in the future. I also would like to thank Professors Gillian Feeley-Harnik and Kelly Askew for their academic and personal support for many years; they understood my challenges in creating a balance between family and work, and shared many insights from their firsthand experiences. I also thank Gillian for her constant and detailed writing advice through several semesters in her ethnolab workshop. I also am grateful to Professor Abé Markus Nornes for insightful comments and warm encouragement during my writing process. I appreciate teaching from professors Bruce Mannheim, the late Fernando Coronil, Damani Partridge, Gayle Rubin, Miriam Ticktin, Tom Trautmann, and Russell Bernard during my coursework period, which helped my research project to take shape in various ways. -

OKINAWA, JAPAN August 16 - 26, 2018

OKINAWA, JAPAN August 16 - 26, 2018 NAHA • ITOMAN • NAKAGAMI • KUNIGAMI • YOMITAN THE GAIL PROJECT: AN OKINAWAN-AMERICAN DIALOGUE Dear UC Santa Cruz Alumni and Friends, I’m writing to invite you along on an adventure: 10 days in Okinawa, Japan with me, a cohort of Gail Project undergraduates and fellow travelers, all exploring the history, tradition, and culture of this unique and significant island. We will visit caves that were once forts in the heart of battle, winding markets with all of the tastes, smells, and colors you can imagine, shrines that will fill you with peace, and artisans who will immerse you into their craft. We will overlook military bases as we think about the American Occupation and the impacts of that relationship. We will eat Okinawan soba (noodles with pork), sample Goya (bitter melon), learn the intricate steps that create the dyed cloth known as Bingata, and dance to traditional Okinawan music. This is a remarkable opportunity for many reasons, as this trip is the first of its kind at UC Santa Cruz. I’m also proud to provide you with a journey unlike any you will have at other universities, as we are fusing the student and alumni experience. Our Gail Project students, while still working on their own undergraduate research, will make special appearances with the travelers and act as docents and guides at various sites along the way. This experience will allow travelers to meet and learn along with the students, and will offer insight into UC Santa Cruz’s commitment to hands-on research opportunities for undergraduates. -

The Ukwanshin Kabudan – Ryukyu/Okinawa

The Ukwanshin Kabudan – Ryukyu/Okinawa performing arts troupe: Transnational network, Glocal connections Yoko Nitahara Souza – UnB - Brazil Short abstract The Ryukyu kingdom (1372-1879) possessed intense court activities, receiving foreign delegations, and then developed an immense scenic and artistic refinement. The Ukuanshin Kabudan Ryukyu performing arts group work for sake of maintaining alive this arts, in Hawaii and in a transnational network. Long abstract The now called Okinawa ken (province) in southern Japan, was the Ryukyu kingdom (1372-1879) also known as land of Courtesy because of its intense diplomatic and trade relations with Southeast Asian countries. In his long and prosper live possessed so intense court activities, receiving foreign delegations, and then developed an immense scenic and artistic refinement. More than mere distraction for foreign delegations at the court of Shuri Castle, artistic performances in music and dance were sacred songs from the Omoro Soshi. Ukwanshin Kabudan was a ship that carried the crown and dignitaries from Ming Emperor in China to be presented to ascending king of Ryukyu, more than this, has been a symbol of exchange and peace for the people of Okinawa. The Ukwanshin Kabudan Ryukyu performing arts troupe work for sake of maintaining alive this arts, in Hawaii as well in a transnational network. In the website of the troupe we can read: we have chosen to travel on a new 'Ukwanshin' to bring our gift of Aloha and gratitude to the people of Okinawa. Okinawa is known as the land of music and dance, and it is through the expression of sound and movements that we find few differences in human feelings and understanding. -

$3988* 2020 Fall

© Naha Navi, Naha City Tourism Association ate n Off the Be n Path: A Different Side of Japa 2020 FALL COMPLETE OKINAWA NAHA ROPE FESTIVAL PACKAGES! Very Unique Tour Itinerary! $3988* 8 Nights / 10 Days • 14 Meals (8 Breakfasts, 2 Lunches, 4 Dinners) Escorted from Honolulu • English-Speaking Local Guide INCLUDES ROUNDTRIP AIRFARE FROM HONOLULU, 8 NIGHTS October 03 – 12, 2020 • Tour Manager: Jennifer Lum-Ota HOTEL, 14 MEALS, TIPS FOR VISIT: Naha • Nanjo • Onna Village • Nago • Manza • Motobu • Nakijin • Kitanakagusuku • Itoman LOCAL TOUR GUIDES AND BUS DRIVERS, ALL TAXES & FEES OVERVIEW: Okinawa is home to a unique culture that differs considerably from that of mainland Japan. Until the islands were invaded by the Satsuma domain (present day Kagoshima Prefecture) in EARLY BOOKING 1609, Okinawa existed as an entirely separate country from Japan, known as the Ryukyu Kingdom. After DISCOUNT PER PERSON the invasion, the Ryukyu Kingdom served as a tributary state to Japan, but continued to be governed $ by the royal family from Shuri Castle. It was not until 1879, a few years after the Meiji Restoration, that SAVE 100 † the kingdom was abolished and incorporated into Japan as Okinawa Prefecture. The castles of Okinawa, BOOK BY DECEMBER 20, 2019 known as “gusuku” in the Okinawan language, are among the most vivid monuments that testify to the unique cultural and historical heritage of the Ryukyu Kingdom. In the year 2000, five castles and four $ related sites were designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the collective title of “Gusuku Sites SAVE 75 † and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu”. -

Okinawa Guide Visiting by Sea Download

Okinawa Guide Visiting By Sea Okinawa was once an important center of trade as the Ryukyu Kingdom. Visit each spot from the port like in ancient time, you can aware the Okinawan new attractions. Naha Cruise Terminal Area Map 天久 You can easily find many interesting spots near Naha Cruise Terminal, including the shopping district of 那覇中環状線 Uenoya Kokusai-dori Street. See the map below for more. Uenoya 新都心公園 おもろまち Tomari 251 黄金森公園 Naha Cruise Terminal 那覇メインプレイス Tomari Ferry Terminal Building (Tomarin) Naha Port Wakasa Park T Galleria Okinawa Wakasa Seaside Park Tomari Wakasa 29 Asato River Ryuchu Dragon Pillars Maejima Naminoue Umisora Park 1 Naminoue Beach Naminoue Rinko Road Wakasa-odori Street 58 Naha Nishi Road 43 Matsuyama Asato Naminoue Shrine 1 Asahigaoka Park Okinawa Prefecture Miebashi Sanmonju Park Station Makishi Matsuyama Park Naha City Traditional Saion Square Tsuji Fukushu-en Garden 2 Arts & Craft Center 4 S a k u Nishi 58 r 39 Midorigaoka Park a Makishi z Asato 222 Ichiba-hondori Street a k Yui Rail a Station Station - n a Kume Heiwa-dori Street k a d 47 o Kokusai-dori Street r 3 i Kumoji S tr ee Tsuboya Uehara Meat Shop t Sangoza Kitchen Prefectural Oce First Makishi Nishi Station Public Market 5 Tsuboya Palette Kumoji Kibogaoka Park 6 Pottery Museum Uenokura-odori Street 7 Tsuboya Yachimun Street Hyatt Regency Kanbara-odori Street Higashi-machi Naha Okinawa Naha City Hall Okinawa Prefectural Oce Matsuo Park Tsuboya 390 Asahibashi 42 46 Station Naha OPA Matsuo Okinawa Prefectural Police Headquarters Kainan-hondori Street Tondo-cho Kainan Seseragi-dori Street Sumiyoshi-cho Naha Bus Terminal泉崎 Himeyuri-dori Street Jogaku Park 330 Asahi-machi Naha City 221 Yorimiya Yogi Park Higawa 0 250m 中央公園 垣花町 市民会館通り 332 Look down below from your ship’s deck and you’ll see the 壺川駅 A Sea Gateway 222 路 vibrant southern seas. -

US$1798.00 Okinawa Tour Spring

Okinawa Tour Spring 6 days 5 nights US$1798.00 Tour Start Dates: 2016 - 4/6 On this tour, you will look deeply into the culture and soul of Japan by visits to festival, museums, temples, shrines, castles, and gardens. Aoi Festival is the festival of Kamigamo Shrine, held on May 15. This festival is one of the most solemn and graceful festivals in the country, and it has been well preserved since the eighth century, when it first started. TOUR COST INCLUDES: 5 nights Western style accommodation TOU Meet and greet upon arrival at Naha Airport R Airport transfers on arrival and departure COS Private luxury coach transfers between destinations in Japan T Comprehensive escorted with AJT professional English speaking tour guide Gratuities DOE S Meals NOT Breakfast everyday INCL 4 lunches and 1 dinners UDE: Internati Admission fees and activities onal Entry fees to sites, gardens, and museums listed in the itinerary Airfares Meals that are not included in the itinerary All prices are per person, based on double or triple occupancy. International flights are not included on our Travel Insuran tours -this allows you the flexibility to choose your own departure and get the best value for your money! We ce can arrange international flights for US customers if needed, please ask for details. Alcoholi c beverag es and All Japan Tours soft 646 W. California St., Ontario, CA 91762, USA drinks Toll Free (US/CANADA): 1-855-325-2726 <1-855-32JAPAN> Persona l TEL: 1-909-988-8885 FAX: 1-909-349-1736 expense E-mail: [email protected] www.alljapantours.com s such as telepho ne and 2 ITINERARY Day 01: Naha Airport Welcome to Naha - the capital and largest city of Okinawa Prefecture. -

The Ryukyus Received 29 February 1972

The Ryukyus Received 29 February 1972 RICHARD PEARSON HE LAST five years have seen a variety of important developments in the archaeology of the Ryukyus. This survey is meant to cover the period from T 1966 to the end of 1971, although earlier important items not introduced previously have been included. Preliminary news of radiocarbon dates for Layer V of the Yamashita Cho site, Naha (32,000 ± 1000 B.P.), and the Minatogawa site of southern Okinawa (about 18,300 B.P.) has brought confirmation to the 'Palaeolithic' ofthe Ryukyus. However, the sites are not without problems. The Yamashita Cho site is virtually without a lithic industry on which to base comparison with other localities in East Asia, the diagnostic artifacts being crudely worked bones, with a total absence of stone artifacts. We eagerly await the report of recent research on the sites by the Ryukyu Cultural Properties Commission and Professor Chokei Watanabe of Tokyo University. Another major contribution in the last few years has been research on the late prehistoric period and the function of the 'castle' or 'gushiku' sites. Several scholars have refined the chronology of the late prehistoric period (roughly the latter part of the first millennium A.D.) and have tackled the problem of the hard gray stoneware or 'sueki' which had largely been overlooked in the past. It is now suggested that this ware is of relatively late manufacture (Nara or Heian period), and that it was imported from Japan (Sato 1970). While it used to be assumed that all 'gushiku' sites were habitations of the lords or 'anji', it is now acknowledged that some of them may have had religious rather than residential functions. -

Ryukyu Sites (Japan)

political centres but also religious stages for the local people of the farming hamlets. At the same time, gusuku sites are Ryukyu sites (Japan) archaeological relics of high academic value and living spiritual centres for contemporary Ryukyuan people, No 972 reflected in the fact that they are still used today by priestesses known as Noro as settings for religious rituals. Sêfa-utaki, which was the religious centre of the entire Ryukyu Kingdom, retains the key features of the Ryukyuan sacred places known as Utaki: dense enclosed forest and picturesque rocks. It is intriguing that Sêfa-utaki commands a view of small islands in the eastern sea between the tree Identification trunks of the dense forest, reminding devout visitors of the old Ryukyuan belief that the land of the gods, Nirai Kanai, is Nomination Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the located far to the east at the end of the sea. In this sense Sêfa- Kingdom of Ryukyu utaki is a cultural landscape closely associated with religious beliefs unique to Ryukyuan nature worship, a living religious Location Okinawa Prefecture tradition still flourishing in the contemporary rituals and festivals of this region. Indeed, the entire nominated property State Party Japan is rooted in the spiritual lives and daily activities of the local people as an active setting for such rituals. Criterion vi Date 25 June 1999 Category of property Two of the three categories of cultural property set out in Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention – Justification by State Party monuments and sites – and also cultural landscapes, as defined in paragraph 39 of the Operational Guidelines for Each of the stone monuments and archaeological sites the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, are included in the nominated property illustrates the unique represented in the nine properties that make up this development and transition that Ryukyu underwent through nomination. -

Comprehensive Preservation and Management Plan for the World Cultural Heritage, “Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu”

Comprehensive Preservation and Management Plan for the World Cultural Heritage, “Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu” March 2013 Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education Comprehensive Preservation and Management Plan for the World Cultural Heritage, “Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu” CONTENTS Chapter 1 Objective and Function of this Plan 1 1. Background and Objective of this Plan ........................................................... 2 2. Comprehensive Preservation and Management Plan .................................... 3 3. Function of this Plan ....................................................................................... 9 4. How this Plan was Developed ........................................................................ 10 Chapter 2 Overview and Existing State of the World Heritage, “Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu” 15 1. Basic Facts Related to World Heritage Inscription ........................................... 16 2. Existing State of the Property ......................................................................... 28 3. Summary of the Existing State of the Property and Perspectives for the Development of this Plan .................................................................................. 41 Chapter 3 Vision and Basic Policies for Comprehensive Preservation and Management 43 1. Vision for Comprehensive Preservation and Management ............................ 44 2. Scope of Comprehensive Preservation and Management ............................