Geologic Trails in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin Report to the Delaware River Basin Commission Upper Delaware River © George Gress Submitted by The Nature Conservancy December 2013 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin December 2013 Report prepared by The Nature Conservancy Michele DePhilip Tara Moberg The Nature Conservancy 2101 N. Front St Building #1, Suite 200 Harrisburg, PA 17110 Phone: (717) 232‐6001 E‐mail: Michele DePhilip, [email protected] Suggested citation: DePhilip, M. and T. Moberg. 2013. Ecosystem flow recommendations for the Delaware River basin. The Nature Conservancy. Harrisburg, PA. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. iii Project Summary ................................................................................................................................... iv Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description and Goals ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Approach ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 2: Project Area and Basin Characteristics .................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Area ................................................................................................................................. -

Delaware River Restoration Fund 2018 Grant Slate

Delaware River Restoration Fund 2018 Grant Slate NFWF CONTACTS Rachel Dawson Program Director, Delaware River [email protected] 202-595-2643 Jessica Lillquist Coordinator, Delaware River [email protected] 202-595-2612 PARTNERS • The William Penn Foundation • U.S. Forest Service • U.S. Department of Agriculture (NRCS) • American Forest Foundation To learn more, go to www.nfwf.org/delaware ABOUT NFWF Delaware River flowing through the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area | Credit: Jim Lukach The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) protects and OVERVIEW restores our nation’s fish and The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and The William Penn Foundation wildlife and their habitats. Created by Congress in 1984, NFWF directs public conservation announced the fifth-year round of funding for the Delaware River Restoration Fund dollars to the most pressing projects. Thirteen new or continuing water conservation and restoration grants totaling environmental needs and $2.2 million were awarded, drawing $3.5 million in match from grantees and generating a matches those investments total conservation impact of $5.7 million. with private funds. Learn more at www.nfwf.org As part of the broader Delaware River Watershed Initiative, the William Penn Foundation provided $6 million in grant funding for NFWF to continue to administer competitively NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS through its Delaware River Restoration Fund in targeted regions throughout the 1133 15th Street, NW Delaware River watershed for the next three years. This year, NFWF is also beginning to Suite 1000 award grants that address priorities in its new Delaware River Watershed Business Plan. Washington, D.C., 20005 Delaware River Restoration Fund grants are multistate investments to restore habitats 202-857-0166 and deliver practices that ultimately improve(continued) and protect critical sources of drinking water. -

. Hikes at The

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Hikes at the Gap Pennsylvania (Mt. Minsi) 4. Resort Point Spur to Appalachian Trail To Mt. Minsi PA from Kittatinny Point NJ This 1/4-mile blue-blazed trail begins across Turn right out of the visitor center parking lot. 1. Appalachian Trail South to Mt. Minsi (white blaze) Follow signs to Interstate 80 west over the river Route 611 from Resort Point Overlook (Toll), staying to the right. Take PA Exit 310 just The AT passes through the village of Delaware Water Gap (40.978171 -75.138205) -- cross carefully! -- after the toll. Follow signs to Rt. 611 south, turn to Mt. Minsi/Lake Lenape parking area (40.979754 and climbs up to Lake Lenape along a stream right at the light at the end of the ramp; turn left at -75.142189) off Mountain Rd.The trail then climbs 1-1/2 that once ran through the basement of the next light in the village; turn right 300 yards miles and 1,060 ft. to the top of Mt. Minsi, with views Kittatinny Hotel. (Look in the parking area for later at Deerhead Inn onto Mountain Rd. About 0.1 mile later turn left onto a paved road with an over the Gap and Mt. Tammany NJ. the round base of the hotel’s fountain.) At the Appalachian Trail (AT) marker to the parking top, turn left for views of the Gap along the AT area. Rock 2. Table Rock Spur southbound, or turn right for a short walk on Cores This 1/4-mile spur branches off the right of the Fire Road the AT northbound to Lake Lenape parking. -

The County of Warren and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy Will Be Hosting a Public Outreach Meeting on Wednesday March 23Rd from 10:00 A.M

The County of Warren and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy will be hosting a public outreach meeting on Wednesday March 23rd from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. at the Warren County Library Headquarters located at 2 Shotwell Drive in Belvidere, NJ, 07823. Please join us to learn how Warren County can become an official Appalachian Trail Community, the benefits of this official designation, and how you can be involved. Spanning 2,190 miles across 14 states, the Appalachian Trail draws 3 million visitors each year. While only about 13 miles of this exceptional trail pass through Warren County, our section along the scenic Kittatinny Ridge boasts: . Natural attractions like the Delaware River, Mount Tammany, Dunnfield Creek, Sunfish Pond, Catfish Pond, Mt. Mohican, and more; . Passage through New Jersey’s Worthington State Forest and the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, which draws up to 5 million visitors per year; . Nearby sites of interest like Turtle Beach, Old Mine Road, Millbrook Village; and the Mohican Outdoor Center. This program will not only help promote Warren County as a natural gateway to the popular Appalachian Trail and the entire Delaware River region, but it will help connect visitors to our inviting communities, our charming downtowns and villages, our farmers and farm markets, as well as all of our other local businesses. This is a wonderful opportunity to connect with the celebrated Appalachian Trail, but we need help from community members like you. We hope you will join us! Harpers Ferry, West Virginia Appalachian Trail Community™ A Designation Program of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) mission is to preserve and manage the Appalachian Trail – ensuring that its vast natural beauty and priceless cultural heritage can be shared and enjoyed today, tomorrow, and for centuries to come. -

NJGS Contracted with Greater New York City Through the Borough of Richmond President Cromwell, to Provide Water for 1835 Staten Island

UNEARTHING NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer 2009 Department of Environmental Protection MESSAGE FROM THE STATE GEOLOGIST A PLAN TO PLUNDER NEW JERSEY’S WATER This issue of Unearthing New Jersey continues the series of historic stories with Mark French’s article A Plan to Plunder New Jersey’s Water. This story concerns a plan by By Mark French the Hudson County Water Company and its myriad political allies to divert an enormous portion of the water resources of INTRODUCTION New Jersey to the City of New York. The scheme was driven At the turn of the 20th century, potable water in New by the desire for private gain at the expense of the citizens of Jersey was managed by private companies or municipalities New Jersey. Thanks to the swift action of the Legislature, the through special grants from the State Legislature or State Attorney General, the State Geologist and the highest certificates of incorporation granted by the State under the courts in the land, the Hudson County Water Company General Incorporation Law of 1875. Clamoring for oversight, plot was stymied setting a riparian rights precedent in the the citizenry and the Legislature tried to create a State process. Water Commission in 1894, but the effort was quashed by A second historic article, The New York-New Jersey Line water business interests and their friends in the Legislature. War by Ted Pallis, Mike Girard and Walt Marzulli discusses Companies were mostly free to traffic in water as they saw the geographic boundaries of New Jersey. -

Climate Change, Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Patrick Gonzalez

Climate Change, Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Patrick Gonzalez Abstract Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities have caused global climate change and widespread impacts on physical systems, ecosystems, and biodiversity. To assist in the integration of climate change science into resource management in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (NRA), particularly the proposed restoration of wetlands at Watergate, this report presents: (1) results of original spatial analyses of historical and projected climate trends at 800 m spatial resolution, (2) results of a systematic scientific literature review of historical impacts, future vulnerabilities, and carbon, focusing on research conducted in the park, and (3) results of original spatial analyses of precipitation in the Vancampens Brook watershed, location of the Watergate wetlands. Average annual temperature from 1950 to 2010 increased at statistically significant rates of 1.1 ± 0.5ºC (2 ± 0.9ºF.) per century (mean ± standard error) for the area within park boundaries and 0.9 ± 0.4ºC (1.6 ± 0.7ºF.) per century for the Vancampens Brook watershed. The greatest temperature increase in the park was in spring. Total annual precipitation from 1950 to 2010 showed no statistically significant change. Few analyses of field data from within or near the park have detected historical changes that have been attributed to human climate change, although regional analyses of bird counts from across the United States (U.S.) show that climate change shifted winter bird ranges northward 0.5 ± 0.3 km (0.3 ± 0.2 mi.) per year from 1975 to 2004. With continued emissions of greenhouse gases, projections under the four emissions scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicate annual average temperature increases of up to 5.2 ± 1ºC (9 ± 2º F.) (mean ± standard deviation) from 2000 to 2100 for the park as a whole. -

To Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania

The Shawangunk Formation (Upper OrdovicianC?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Depa rtm ent of Enviro nm ental Resources^ Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey The Shawangunk Formation (Upper Ordovician (?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania By JACK B. EPSTEIN and ANITA G. EPSTEIN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey Statigraphy, petrography, sedimentology, and a discussion of the age of a lower Paleozoic fluvial and transitional marine clastic sequence in eastern Pennsylvania UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-189667 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 65 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2098 CONTENTS Page Abstract _____________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________ 1 Shawangunk Formation ___________________________________ 1 Weiders Member __________ ________________________ 2 Minsi Member ___________________________________ 5 Lizard Creek Member _________________________________ 7 Tammany Member _______________________________-_ 12 Age of the Shawangunk Formation _______ __________-___ 14 Depositional environments and paleogeography _______________ 16 Measured sections ______________________________________ 23 References cited ________________________________________ 42 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Generalized geologic map showing outcrop belt of the Shawangunk Formation in eastern Pennsylvania and northwestern New Jersey ___________________-_ 3 2. Stratigraphic section of the Shawangunk Formation in the report area ___ 3 3-21. Photographs showing 3. Conglomerate and quartzite, Weiders Member, Lehigh Gap ____ 4 4. -

Chapter 2 Delaware's Wildlife Habitats

CHAPTER 2 DELAWARE’S WILDLIFE HABITATS 2 - 1 Delaware Wildlife Action Plan Contents Chapter 2, Part 1: DELAWARE’S ECOLOGICAL SETTING ................................................................. 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 9 Delaware Habitats in a Regional Context ..................................................................................... 10 U.S. Northeast Region ............................................................................................................. 10 U.S. Southeast Region .............................................................................................................. 11 Delaware Habitats in a Watershed Context ................................................................................. 12 Delaware River Watershed .......................................................................................................13 Chesapeake Bay Watershed .....................................................................................................13 Inland Bays Watershed ............................................................................................................ 14 Geology and Soils ......................................................................................................................... 17 Soils .......................................................................................................................................... 17 EPA -

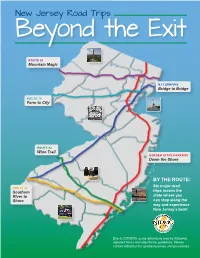

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

Delaware Water Gap U.S

National Park Service Delaware Water Gap U.S. Department of the Interior National Recreation Area Summer/Fall 2015 Guide to the Gap N A YEARS A T E I 50 1965-2015 R O A N N AL IO RECREAT Your National Park Celebrates 50 Years! The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was established by a park for the people. Today, visitors roam a landscape carved by uplift, Congress on September 1, 1965, to preserve the natural, culture, and scenic erosion, and glacial activity that is marked by hemlock and rhododendron- resources of the Delaware River Valley and provide opportunities for laced ravines, rumbling waterfalls, fertile floodplains and is rich with recreation, education, and enjoyment to the most densely populated region archaeological evidence and historic narratives. This haven for natural of the nation. Sprung out of the Tocks Island Dam controversy, the last and cultural stories is your place, your park, and we invite you to celebrate 50 years has solidified Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area as with us in 2015. The River, the Valley, and You . 2 Events. 4 Delaware River . 6 Park Trails . 8. Fees and Passes . 2 Park Map and Visitor Centers . 3 Are you curious about the natural and cultural Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area From ridgetop to riverside, vistas to ravines, Activities and Events in 2015 . 4 history of the area? Would you like to see includes nearly 40 miles of the free-flowing from easy to extreme, more than 100 Delaware River Water Trail . 6 artisans at work? Want to experience what it Middle Delaware River Scenic and Recreational miles of trail offer something for every mood. -

SP20 Delaware Piedmont Geology

Delaware Piedmont Geology including a guide to the rocks of Red Clay Valley RESEARCH DELAWARE SERVICEGEOLOGICAL SURVEY EXPLORATION Delaware Geological Survey University of Delaware Special Publication No. 20 By Margaret O. Plank and William S. Schenck 106/1500/298/C Delaware Piedmont Geology Including a guide to the rocks of Red Clay Valley Delaware Geological Survey University of Delaware Special Publication No. 20 Margaret O. Plank and William S. Schenck 1998 Contents FOREWORD . v INTRODUCTION . vii Acknowledgments . viii BASIC FACTS ABOUT ROCKS . 1–13 Our Earth . 1 Crust . 1 Mantle . 2 Core. 2 Plate Tectonics . 3 Minerals . 5 Rocks . 6 Igneous Rocks . 6 Sedimentary Rocks. 8 Metamorphic Rocks . 9 Deformation. 11 Time . 12 READING THE ROCKS: A HISTORY OF THE DELAWARE PIEDMONT . 15–29 Geologic Setting . 15 Piedmont . 15 Fall Line. 17 Atlantic Coastal Plain. 17 Rock Units of the Delaware Piedmont . 20 Wilmington Complex . 20 Wissahickon Formation . 21 Setters Formation & Cockeysville Marble . 22 Geologic Map for Reference . 23 Baltimore Gneiss . 24 Deformation in the Delaware Piedmont . 24 The Piedmont and Plate Tectonics . 27 Red Clay Valley: Table of Contents iii A GUIDE TO THE ROCKS ALONG THE TRACK . 31–54 Before We Begin . 31 Geologic Points of Interest . 31 A Southeast of Greenbank . 35 B Workhouse Quarry at Greenbank. 36 C Red Clay Creek and Brandywine Springs Park . 36 D Brandywine Springs to Faulkland Road . 38 E Hercules Golf Course . 39 F Rock Cut at Wooddale . 40 G Wissahickon Formation at Wooddale. 43 H Quarries at Wooddale. 43 I Red Clay Creek Flood Plain . 44 J Mount Cuba . 44 K Mount Cuba Picnic Grove . -

And Eastern Pennsylvania

GEOLOGY OF THE RIDGE AND VALLEY PROVINCE, NORTHWESTERN NEW JERSEY AND EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA JACK B. EPSTEIN U. S. Geological Survey, Reston, Va. 22092 INTRODUCTION The rocks seen in this segment of the field trip range A general transgressive-shelf sequence followed in age from Middle Ordovician to Middle Devonian and characterized mainly by tidal sediments and barrier bars constitute a.deep basin-continental-shallow shelf succes (Poxono Island, Bossardville, Decker, Rondout)~ suc sion. Within this succession, three lithotectonic units, or ceeded by generally subtidal and bar deposits (Helder sequences of rock that were deformed semi burg and Oriskany Groups), and then by deeper sub independently of each other, have somewhat different tidal deposits (Esopus, . Schoharie. and Buttermilk structural characteristics. Both the Alleghenian and Falls), finally giving way to another deep~water to Taconic orogenies have left their imprint on the rocks. shoaling sequence (Marcellus Shale through the Catskill Wind and water gaps are structurally controlled, thus Formation). Rocks of the Marcellus through Catskill placing doubt upon the hypothesis of regional super will not be seen on this trip. position. Wisconsinan deposits and erosion effects are common. We will examine these geologic features as This vertical stratigraphic sequence is complicated a well as some of the economic deposits in the area. bit because most Upper Silurian and Lower Devonian units are much thinner or are absent toward a paleo Figure 1 is an index map of the field-trip area, show positive area a few tens of miles southwest of the field ing the trip route and quadrangle coverage. Figure 2 is a trip area.