Gray Power and Popular Protest in Rural China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

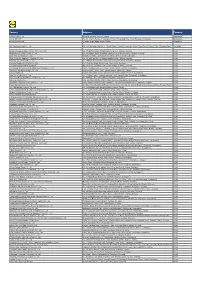

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 18

Factory Factory Address Country Sector FTE No. workers % Male % Female ESSENTIAL CLOTHING LTD Akulichala, Sakashhor, Maddha Para, Kaliakor, Gazipur, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 669 55% 45% NANTONG AIKE GARMENTS COMPANY LTD Group 14, Huanchi Village, Jiangan Town, Rugao City, Jaingsu Province, China CHINA Garments 159 22% 78% DEEKAY KNITWEARS LTD SF No. 229, Karaipudhur, Arulpuram, Palladam Road, Tirupur, 641605, Tamil Nadu, India INDIA Garments 129 57% 43% HD4U No. 8, Yijiang Road, Lianhang Economic Development Zone, Haining CHINA Home Textiles 98 45% 55% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% 17% ASIAN LEATHERS LIMITED Asian House, E. M. Bypass, Kasba, Kolkata, 700017, India INDIA Accessories 978 77% 23% AMAN KNITTINGS LIMITED Nazimnagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 1708 60% 30% V K FASHION LTD formerly STYLEWISE LTD Unit 5, 99 Bridge Road, Leicester, LE5 3LD, United Kingdom UK Garments 51 43% 57% AMAN GRAPHIC & DESIGN LTD. Najim Nagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 3260 40% 60% WENZHOU SUNRISE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. Floor 2, 1 Building Qiangqiang Group, Shanghui Industrial Zone, Louqiao Street, Ouhai, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China CHINA Accessories 716 58% 42% AMAZING EXPORTS CORPORATION - UNIT I Sf No. 105, Valayankadu, P. Vadugapal Ayam Post, Dharapuram Road, Palladam, 541664, India INDIA Garments 490 53% 47% ANDRA JEWELS LTD 7 Clive Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex, TN35 5LD, United Kingdom UK Accessories 68 CAVENDISH UPHOLSTERY LIMITED Mayfield Mill, Briercliffe Road, Chorley Lancashire PR6 0DA, United Kingdom UK Furniture 33 66% 34% FUZHOU BEST ART & CRAFTS CO., LTD No. 3 Building, Lifu Plastic, Nanshanyang Industrial Zone, Baisha Town, Minhou, Fuzhou, China CHINA Homewares 44 41% 59% HUAHONG HOLDING GROUP No. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail. -

Summarized Annual Report 2009

Summarized Annual Report 2009 01/ PAGE PAGE /02 Summarized Annual Report 2009 Everything Is For Growing-up Together 03/ PAGE PAGE /04 Summarized Annual Report 2009 05/ PAGE PAGE /06 Summarized Annual Report 2009 07/ PAGE PAGE /08 Summarized Annual Report 2009 09/ PAGE PAGE /10 Summarized Annual Report 2009 11/ PAGE PAGE /12 Summarized Annual Report 2009 13/ PAGE PAGE /14 Summarized Annual Report 2009 15/ PAGE PAGE /16 Summarized Annual Report 2009 17/ PAGE PAGE /18 Summarized Annual Report 2009 19/ PAGE PAGE /20 Summarized Annual Report 2009 ZHEJIANG TAILONG COMMERCIAL BANK CO., LTD. Section II Brief Introduction to the Company 2009 Summarized Annual Report 1. Legal Company Name in Chinese: Section I Important Notice (Chinese abbreviation: ) Legal Company Name in English: Zhejiang Tailong Commercial Bank Co., Ltd. 1. The Board of Directors of the Company and all its directors guarantee that the information presented (Hereinafter referred to as the "Company" ) in this report is free from any false record, misleading statement or material omission, and ac cept, individually and collectively, liability for its truthfulness, accuracy and completeness. 2. Legal Representative: Wang Jun 2. According to the requirements of the new accounting standards, the annual financial report of the 3. Director of the General Office of Board of Directors: You Dinghai Company were audited by Zhonghui Certified Public Accountants Ltd. in accordance with PRC generally Address: 188 Nanguan Avenue, Luqiao District, Taizhou, Zhejiang Province General Office of Board accepted auditing principles, and have obtained auditor's report of standard unqualified opinion. of Directors of the Company Tel : 0086-576-82550003 3. -

History and Corporate Structure

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT HISTORY AND CORPORATE STRUCTURE OVERVIEW Our history traced back to the establishment of our Predecessor Company in the PRC on 5 May 1993 as a limited liability company. Our Predecessor Company commenced the water supply service in Taizhou in December 1995. Pursuant to the Founders Agreement, our Predecessor Company was converted into our Company, a joint stock company with limited liability, on 30 June 1999 and our registered capital was increased to RMB149.13 million through contribution of net assets of our Predecessor Company and cash by our Founders. Our Company adopted its current name “Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd.” (台州市水務集 團股份有限公司) on 23 May 2016. KEY MILESTONES Below sets out the key milestones of our business development: May 1993 our Predecessor Company was established. December 1995 our Predecessor Company commenced the business of water supply service December 1996 the leading group of Huang-Jiao-Wen Joint Water Supply Project (黃椒温聯合供水指揮部) transferred the assets of Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase I) June 1999 our Predecessor Company was converted into a joint stock limited liability company [February 2004] participation in the construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase II) commenced [December 2008] completion of the construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase II) May 2015 our project proposal on the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase III) was accepted by Taizhou DRC February 2018 construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase III) commenced. -

Hangzhou Qiantang River Electric Group Co., Ltd

Hangzhou Qiantang River Electric Group Co., Ltd. A. Sales Reference in GCC Through Chinese Trading Company 2008.08.06 1MVA 11/0.416kV 1 QRE-IRAQ-08-01 IRAQ Ningbo Ville Enterprise Co., Ltd.( 630kVA 6.6/0.42kV 6 1600kVA Tel:86-574-88867775 3 QRE-IRANSTEEL-080 2008.07.19 6.6/0.42kV : 701 Fax 86-574-88867774 2000kVA 6 IRAN 6.6/0.42kV Aryana Petro Tavan Unit 264, 6th floor, Vali Asr-2 building, No. 31500kVA 2 2008.3.12 7, 36th St., Vali Asr Ave., Tehran 15167, 33/6.3kV QRE-Iran/trf-Arvand/PI2 IRAN 00801 Tel: (+98-21) 88 64 78 51 - 3 Fax: (+98-21) 88 64 78 46 2500kVA 6/0.42kV 2 Payvand Golestan Cement Co. 2500kVA 6/0.42kV 6 km.6 of Galikesh city of Golestan Province 2000kVA 6/0.42kV 1 0901/PGC-QRE/TRF/SU 2009-4-11 and around Nilkouh (Nil Fountain) PPLY www.pgcement.ir 1600kVA 6/0.42kV 2 Mr. Haj Abbas Gholi: (+98-912) 112 78 89 1 Hangzhou Qiantang River Electric Group Co., Ltd. B. Power Transformer Sales Reference (Chinese part) 1. 220kV Transformer Date Customer Type Qty. Contract No. Orient Hope Baotou Aluminum Industry 31.5MVA ONAN 220/10.5kV Power 2 Co., Ltd.(Mongolia) transformer 15.05.2003 RE High-tech Industrial Zone, Q-HBT-0602 200MVA ODAF 13.8/242kV Baotou City, NM.CN 2 Generator transformer Phone:0472-5959387 Henan Wanji Aluminum Industry Co., Ltd. 90MVA ONAF 220/35/10.5kV Power 12.04.2004 Wanji Industrial District, Xin’an 2 QT90MVA-0405 transformer County, Henan Province, China. -

1 China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited

CHINA JINJIANG ENVIRONMENT HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED 中国锦江环境控股有限公司 (Company Registration Number: 245144) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands on 8 September 2010) China International Capital Corporation (Singapore) Pte. Limited was the sole issue manager, global coordinator, bookrunner and underwriter (the “Sole Issue Manager, Global Coordinator, Bookrunner and Underwriter”) for the initial public offering of shares in, and listing of, China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited on the Mainboard of the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited. The Sole Issue Manager, Global Coordinator, Bookrunner and Underwriter assumes no responsibility for the contents of this announcement. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF ZHEJIANG ZHUJI BAFANG THERMAL POWER CO., LTD. (浙江诸暨八方热电有限责任公司) AND WENLING GREEN NEW ENERGY CO., LTD. (温岭绿能新能 源有限公司) 1. INTRODUCTION The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited (the “Company” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”) wishes to announce that its wholly-owned subsidiary Gevin Limited (“Gevin”) has on 5 October 2016 entered into the following agreements: (a) a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Hangzhou Jinjiang Group Co., Ltd. ( 杭 州 锦 江 集 团 有 限 公 司 ) (“Jinjiang Group”), a controlling shareholder of the Company, dated 5 October 2016 (the “Zhuji S&P Agreement”) for the acquisition by Gevin, or any of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, of the entire equity interest in Zhejiang Zhuji Bafang Thermal Power Co., Ltd. (浙江诸暨八方热电有限责任公司) (“Zhuji Bafang”) from Jinjiang Group for a total consideration of RMB304,494,000 (equivalent to approximately S$62,482,100) (the “Zhuji Acquisition Consideration”) (the “Proposed Zhuji Acquisition”); and (b) a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Jinjiang Group dated 5 October 2016 (the “Wenling S&P Agreement”) for the acquisition by Gevin, or any of its wholly- owned subsidiaries, of the entire equity interest in Wenling Green New Energy Co., Ltd. -

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord's Suppliers for Apparel

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord‘s Suppliers for Apparel, Home Textiles and Shoes Version: April 2021 Produktionsstättenliste | März 2018 | Seite 0/17 Name Address Number of Employees Commodity Group Bangladesh AB Apparels Ltd. 225, Singair Road, Tetuljhora, Hemayetpur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Ador Composite Ltd. 1, C & B Bazar, Gilarchala, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles AKH Eco Apparels Ltd. 495, Balitha, Shahbelishwar, Dhamrai 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Angshuk Ltd. 133-134, Hamayetpur, Savar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Apparels Village Ltd. Khagan, Birulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Aspire Garments Ltd. 491, Dhalla, Singair 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles B.H.I.S. Apparels Ltd. 671, Datta Para, Hossain Market, Tongi 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Blue Planet Knitwear Ltd. Mulaid, P.O.: Tengra, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Chaity Composite Ltd. Chotto Silmondi, Tripurdi, Sonargaon 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Chantik Garments Ltd. Kumkumari, Gouripur, Ashulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Chorka Textile Ltd. Kajirchor, Danga Bazar, Polash 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Citadel Apparels Ltd. Joy Bangla Road, Kunia, K.B. Bazar, Gazipur Sadar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Cotton Dyeing & Finishing Mills Ltd. Vill: Amtoli, Union: 10 No. Habirbari, P.O-Seedstore Bazar, P.S.-Valuka 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Crossline Factory (Pvt) Ltd. 25, Vadam, Uttarpara, Nishatnagar, Tongi 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Plot No. 45, 48, 49, 51 & 52; Holding No.: 3/C, Vadam, P.O.: Crossline Knit Fabrics Ltd. 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Nishatnagar, Tongi, Gazipur-1711, Gazipur Crown Exclusive Wears Ltd. Mawna, Sreepur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Crown Fashion & Sweater Industries Ltd. Plot No. 781-782, Vogra, Joydebpur, Gazipur-1704 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Denim Fashions Ltd. -

The Design of the Traffic Plan of Line S1 of Taizhou Railway in Zhejiang Province

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science PAPER • OPEN ACCESS The design of the traffic plan of line S1 of Taizhou railway in Zhejiang Province To cite this article: Zimu Li 2021 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 791 012079 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.33.42 on 24/09/2021 at 21:19 ACCESE 2021 IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 791 (2021) 012079 doi:10.1088/1755-1315/791/1/012079 The design of the traffic plan of line S1 of Taizhou railway in Zhejiang Province Zimu LI1* 1 College of Transport and Communications, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201304, China *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. At present, China is in the period of rapid urbanization construction, and gradually build a set of efficient, new and fast comprehensive urban transportation system. The urban railway construction with the same city commuter and convenient public transport service can effectively extend the urban development space and accelerate the adjustment process of urban planning and layout. According to the current situation of Taizhou's economic and traffic development, as well as Taizhou's unique geographical advantages, combined with the relevant research at home and abroad, this paper comprehensively discusses the necessity of building Taizhou City railway line S1. By sorting out the relevant preliminary, short-term and long-term passenger flow forecast data, this paper calculates the maximum section passenger flow in each period of the day, analyzes the characteristics of passenger flow in each period, compiles the full-time driving plan compilation data, and makes corresponding adjustments according to the actual situation, and finally designs the full-time driving plan to meet the passenger flow demand in each period. -

Annual Report 2019

台州市水務集團股份有限公司 Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd.* (a joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock code : 1542 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 * For identification purposes only CONTENT Corporate Information 2 Definitions 4 Financial Highlights 7 Chairman’s Statement 8 Management Discussion and Analysis 10 Biographies of Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 18 Report of Directors 27 Report of the Supervisory Committee 45 Corporate Governance Report 47 Independent Auditor’s Report 59 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 64 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 65 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 67 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 68 Notes to Financial Statements 70 Four-Year Financial Summary 128 2 Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd. // Annual Report 2019 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS AUDIT COMMITTEE Executive Directors Mr. Li Wai Chung (Chairman) Mr. Yan Chuanhua (Note) (Chairman of the Board) Mr. Wang Haiping Mr. Zhang Junzhou Ms. Hou Meiwen Non-executive Directors STRATEGY COMMITTEE Mr. Wang Haibo Mr. Yan Chuanhua (Chairman) Mr. Wang Haiping Mr. Zhang Junzhou Ms. Fang Ya Mr. Wang Haibo Mr. Yu Yangbin Ms. Fang Ya Ms. Huang Yuyan Ms. Huang Yuyan Mr. Yang Yide Mr. Zheng Jianzhuang Mr. Guo Dingwen Mr. Ye Jianhua (resigned on 10 March 2020) Mr. Ye Jianhua (resigned on 10 March 2020) JOINT COMPANY SECRETARIES Independent Non-Executive Directors Ms. Chen Liying Mr. Zheng Jianzhuang Ms. Siu Pui Wah Ms. Lin Suyan Ms. Hou Meiwen AUTHORISED REPRESENTATIVES Mr. Li Wai Chung Mr. Yan Chuanhua Mr. Wang Yongyue Ms. Siu Pui Wah REMUNERATION COMMITTEE REGISTERED OFFICE AND PRINCIPAL Mr. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 17

FTE No. Factory Name Factory Address Country Sector % M workers (BSQ) BAISHIQING CLOTHING First and Second Area, Donghaian Industrial Zone, Shenhu Town, Jinjiang China CHINA Garments 148 35% (UNITED) ZHUCHENG TIANYAO GARMENTS CO., LTD Zangkejia Road, Textile & Garment Industrial Park, Longdu Subdistrict, Zhucheng City, Shandong Province, China CHINA Garments 332 19% ABHIASMI INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD Plot No. 186, Sector 25 Part II, Huda, Panipat-132103, Haryana India INDIA Home Textiles 336 94% ABHITEX INTERNATIONAL Pasina Kalan, GT Road Painpat, 132103, Panipat, Haryana, India INDIA Homewares 435 99% ABLE JEWELLERY MFG. LTD Flat A9, West Lianbang Industrial District, Yu Shan xi Road, Panyu, Guangdong Province, China CHINA Jewellery 178 40% ABLE JEWELLERY MFG. LTD Flat A9, West Lianbang Industrial District, Yu Shan xi Road, Panyu, Guangdong Province, China HONG KONG Jewellery 178 40% AFROZE BEDDING UNIT LA-7, Block 22, Federal B Area, Karachi, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 980 97% AFROZE TOWEL UNIT Plot No. C-8, Scheme 33, S. I. T.E, Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 960 97% AGEME TEKSTIL KONFEKSIYON INS LTD STI (1) Sari Hamazli Mah, 47083 Sok No. 3/2A, Seyhan, Adana, Turkey TURKEY Garments 350 41% AGRA PRODUCTS LTD Plot 94, 99 NSEZ, Phase 2, Noida 201305, U. P., India INDIA Jewellery 377 100% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495 Balitha, Shah Belishwer, Dhaamrai, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 5305 56% AL RAHIM Plot A-188, Site Nooriabad, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 1350 100% AL-KARAM TEXTILE MILLS PVT LTD Ht-11, Landhi Industrial Area, Karachi.