Scale Farming Operations in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd. 台州市水務集團股份有限公司

The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission take no responsibility for the contents of this Post Hearing Information Pack, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Post Hearing Information Pack. Post Hearing Information Pack of Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd.* 台州市水務集團股份有限公司 (the “Company”) (a joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) WARNING The publication of this Post Hearing Information Pack is required by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Exchange”)/ the Securities and Futures Commission (the “Commission”) solely for the purpose of providing information to the public in Hong Kong. This Post Hearing Information Pack is in draft form. The information contained in it is incomplete and is subject to change which can be material. By viewing this document, you acknowledge, accept and agree with the Company, its sole sponsor, advisers or member of the underwriting syndicate that: (a) this document is only for the purpose of providing information about the Company to the public in Hong Kong and not for any other purposes. No investment decision should be based on the information contained in this document; (b) the publication of this document or supplemental, revised or replacement pages on the Exchange’s website does not give rise to any obligation of the Company, its sole sponsor, advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate to proceed with an offering in Hong Kong or any other jurisdiction. -

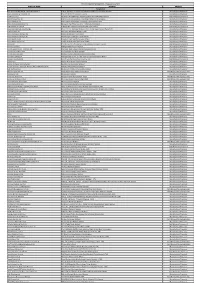

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Distribution Dynamics and Convergence Among 75 Cities and Counties in Yangtze River Delta in China: 1990-2005

Distribution Dynamics and Convergence among 75 Cities and Counties in Yangtze River Delta in China: 1990-2005 Hiroshi Sakamoto, ICSEAD and Jin Fan, Research Centre for Jiangsu Applied Economics, Jiangsu Administration Institute Working Paper Series Vol. 2009-25 November 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. No part of this article may be used reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews. For information, please write to the Centre. The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development, Kitakyushu Distribution Dynamics and Convergence among 75 Cities and Counties in Yangtze River Delta in China: 1990-2005 Hiroshi Sakamoto♦ Jin Fan∗ Abstract This paper applies the distribution dynamics method to study the per capita income disparity from 1990 to 2005 among the 75 cities and counties in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD). The main conclusions are as follows: First, the distribution of per capita income across YRD has changed from bi-modal to being positively skewed over the period 1990–2005; the income disparity has been reduced in the 8th Five-Year Plan, enlarged in the 9th Five-Year Plan and then reduced again somewhat in the 10th Five-Year Plan. Second, the main contribution to disparity comes from the intra disparity of the Jiangsu region; especially, the distribution density of Jiangsu is bi-modal over the period. Third, the rich cities and the poor cities developed independently and steadily at different speeds. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 18

Factory Factory Address Country Sector FTE No. workers % Male % Female ESSENTIAL CLOTHING LTD Akulichala, Sakashhor, Maddha Para, Kaliakor, Gazipur, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 669 55% 45% NANTONG AIKE GARMENTS COMPANY LTD Group 14, Huanchi Village, Jiangan Town, Rugao City, Jaingsu Province, China CHINA Garments 159 22% 78% DEEKAY KNITWEARS LTD SF No. 229, Karaipudhur, Arulpuram, Palladam Road, Tirupur, 641605, Tamil Nadu, India INDIA Garments 129 57% 43% HD4U No. 8, Yijiang Road, Lianhang Economic Development Zone, Haining CHINA Home Textiles 98 45% 55% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% 17% ASIAN LEATHERS LIMITED Asian House, E. M. Bypass, Kasba, Kolkata, 700017, India INDIA Accessories 978 77% 23% AMAN KNITTINGS LIMITED Nazimnagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 1708 60% 30% V K FASHION LTD formerly STYLEWISE LTD Unit 5, 99 Bridge Road, Leicester, LE5 3LD, United Kingdom UK Garments 51 43% 57% AMAN GRAPHIC & DESIGN LTD. Najim Nagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 3260 40% 60% WENZHOU SUNRISE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. Floor 2, 1 Building Qiangqiang Group, Shanghui Industrial Zone, Louqiao Street, Ouhai, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China CHINA Accessories 716 58% 42% AMAZING EXPORTS CORPORATION - UNIT I Sf No. 105, Valayankadu, P. Vadugapal Ayam Post, Dharapuram Road, Palladam, 541664, India INDIA Garments 490 53% 47% ANDRA JEWELS LTD 7 Clive Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex, TN35 5LD, United Kingdom UK Accessories 68 CAVENDISH UPHOLSTERY LIMITED Mayfield Mill, Briercliffe Road, Chorley Lancashire PR6 0DA, United Kingdom UK Furniture 33 66% 34% FUZHOU BEST ART & CRAFTS CO., LTD No. 3 Building, Lifu Plastic, Nanshanyang Industrial Zone, Baisha Town, Minhou, Fuzhou, China CHINA Homewares 44 41% 59% HUAHONG HOLDING GROUP No. -

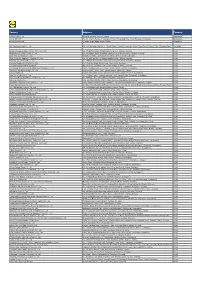

TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS M Ns Garments Printing & Embroidery

TIER 2 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced July 2021 TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS Bangladesh Mns Garments Printing & Embroidery (Unit 2) House 305 Road 34 Hazirpukur Choydana National University Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor (A&E) American & Efird (Bd) Ltd Plot 659 & 660 93 Islampur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor A G Dresses Ltd Ag Tower Plot 09 Block C Tongi Industrial Area Himardighi Gazipur Next Branded Component Abanti Colour Tex Ltd Plot S A 646 Shashongaon Enayetnagar Fatullah Narayanganj Manufacturer/Processor Aboni Knitwear Ltd Plot 169 171 Tetulzhora Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Manufacturer/Processor Afrah Washing Industries Ltd Maizpara Taxi Track Area Pan - 4 Patenga Chottogram Manufacturer/Processor AKM Knit Wear Limited Holding No 14 Gedda Cornopara Ulail Savar Dhaka Next Branded Component Aleya Embroidery & Aleya Design Hose 40 Plot 808 Iqbal Bhaban Dhour Nishat Nagar Turag Dhaka 1230 Manufacturer/Processor Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 Manufacturer/Processor Aman Fashions & Designs Ltd Nalam Mirzanagar Asulia Savar Manufacturer/Processor Aman Graphics & Design Ltd Nazimnagar Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Sweaters Ltd Rajaghat Road Rajfulbaria Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Winter Wears Ltd Singair Road Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Amann Bd Plot No Rs 2497-98 Tapirbari Tengra Mawna Shreepur Gazipur Next Branded Component Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor Ananta Apparels Ltd - Adamjee Epz Plot 246 - 249 Adamjee Epz Narayanganj -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail. -

Summarized Annual Report 2009

Summarized Annual Report 2009 01/ PAGE PAGE /02 Summarized Annual Report 2009 Everything Is For Growing-up Together 03/ PAGE PAGE /04 Summarized Annual Report 2009 05/ PAGE PAGE /06 Summarized Annual Report 2009 07/ PAGE PAGE /08 Summarized Annual Report 2009 09/ PAGE PAGE /10 Summarized Annual Report 2009 11/ PAGE PAGE /12 Summarized Annual Report 2009 13/ PAGE PAGE /14 Summarized Annual Report 2009 15/ PAGE PAGE /16 Summarized Annual Report 2009 17/ PAGE PAGE /18 Summarized Annual Report 2009 19/ PAGE PAGE /20 Summarized Annual Report 2009 ZHEJIANG TAILONG COMMERCIAL BANK CO., LTD. Section II Brief Introduction to the Company 2009 Summarized Annual Report 1. Legal Company Name in Chinese: Section I Important Notice (Chinese abbreviation: ) Legal Company Name in English: Zhejiang Tailong Commercial Bank Co., Ltd. 1. The Board of Directors of the Company and all its directors guarantee that the information presented (Hereinafter referred to as the "Company" ) in this report is free from any false record, misleading statement or material omission, and ac cept, individually and collectively, liability for its truthfulness, accuracy and completeness. 2. Legal Representative: Wang Jun 2. According to the requirements of the new accounting standards, the annual financial report of the 3. Director of the General Office of Board of Directors: You Dinghai Company were audited by Zhonghui Certified Public Accountants Ltd. in accordance with PRC generally Address: 188 Nanguan Avenue, Luqiao District, Taizhou, Zhejiang Province General Office of Board accepted auditing principles, and have obtained auditor's report of standard unqualified opinion. of Directors of the Company Tel : 0086-576-82550003 3. -

A New Approach to Identify Social Vulnerability to Climate Change in the Yangtze River Delta

sustainability Article A New Approach to Identify Social Vulnerability to Climate Change in the Yangtze River Delta Yi Ge 1,*, Wen Dou 2 and Jianping Dai 3 1 State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control & Resource Re-use, School of the Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China 2 School of Transportation, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Philosophy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 October 2017; Accepted: 2 December 2017; Published: 4 December 2017 Abstract: This paper explored a new approach regarding social vulnerability to climate change, and measured social vulnerability in three parts: (1) choosing relevant indicators of social vulnerability to climate change; (2) based on the Hazard Vulnerability Similarity Index (HVSI), our method provided a procedure to choose the referenced community objectively; and (3) ranked social vulnerability, exposure, sensitivity, and adaptability according to profiles of similarity matrix and specific attributes of referenced communities. This new approach was applied to a case study of the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region and our findings included: (1) counties with a minimum and maximum social vulnerability index (SVI) were identified, which provided valuable examples to be followed or avoided in the mitigation planning and preparedness of other counties; (2) most counties in the study area were identified in high exposure, medium sensitivity, low adaptability, and medium SVI; (3) -

Interim Report 2019

INTERIM REPORT 2019 2019 INTERIM REPORT www.cs.ecitic.com I M P O R T A N T N O T I C E The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and the Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of contents of this interim report and that there is no false representation, misleading statement contained herein or material omission from this interim report, for which they will assume joint and several liabilities. This interim report was considered and approved at the 44th Meeting of the Sixth Session of the Board. All Directors attended the meeting. No Director raised any objection to this interim report. The 2019 interim financial statements of the Company were unaudited. PricewaterhouseCoopers Zhong Tian LLP and PricewaterhouseCoopers issued review opinions in accordance with the China and international review standards, respectively. Mr. ZHANG Youjun, head of the Company, Mr. LI Jiong, the person-in-charge of accounting affairs and Ms. KANG Jiang, head of the Company’s accounting department, warrant that the financial statements set out in this interim report are true, accurate and complete. There was no profit distribution plan or plan of conversion of the capital reserve into the share capital of the Company for the first half of 2019. Forward looking statements, including future plans and development strategies, contained in this interim report do not constitute a substantive commitment to investors by the Company. Investors should be aware of investment risks. There was no appropriation of funds of the Company by the related/connected parties for non-operating purposes. -

Supplementary Figure 1. Forest Plot Showing the Proportion of Ascites in Patients with Tusanqi- Related SOS

Supplementary Figure 1. Forest plot showing the proportion of ascites in patients with tusanqi- related SOS. Supplementary Figure 2. Forest plot showing the proportion of hepatomegaly in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 3. Forest plot showing the proportion of jaundice in patients with tusanqi- related SOS. Supplementary Figure 4. Forest plot showing the proportion of plueral effusion in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 5. Forest plot showing the proportion of lower limbs edema in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 6. Forest plot showing the proportion of splenomegaly in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 7. Forest plot showing the proportion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 8. Forest plot showing the proportion of gastroesophageal varices in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Figure 9. Forest plot showing the proportion of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with tusanqi-related SOS. Supplementary Table 1. Exclusion of relevant studies with overlapping data Type Excluded First of Affiliations Journals or author papers included Zhang Yao Wu Bu Liang Fan Ying Za Zhi 2009;11(6);425-426 Excluded Beijing Ditan Hospital Junxia Affiliated to Capital Cheng Medical University Zhong Guo Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2012;4(4);26-28 Included Danying Wu Shi Yong Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2010;13(2);139-140 Excluded Nanjing General Hospital Xiaowei of Nanjing Military Hou Command Hu Li Yan Jiu 2011;25(1);178-179 -

History and Corporate Structure

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT HISTORY AND CORPORATE STRUCTURE OVERVIEW Our history traced back to the establishment of our Predecessor Company in the PRC on 5 May 1993 as a limited liability company. Our Predecessor Company commenced the water supply service in Taizhou in December 1995. Pursuant to the Founders Agreement, our Predecessor Company was converted into our Company, a joint stock company with limited liability, on 30 June 1999 and our registered capital was increased to RMB149.13 million through contribution of net assets of our Predecessor Company and cash by our Founders. Our Company adopted its current name “Taizhou Water Group Co., Ltd.” (台州市水務集 團股份有限公司) on 23 May 2016. KEY MILESTONES Below sets out the key milestones of our business development: May 1993 our Predecessor Company was established. December 1995 our Predecessor Company commenced the business of water supply service December 1996 the leading group of Huang-Jiao-Wen Joint Water Supply Project (黃椒温聯合供水指揮部) transferred the assets of Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase I) June 1999 our Predecessor Company was converted into a joint stock limited liability company [February 2004] participation in the construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase II) commenced [December 2008] completion of the construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase II) May 2015 our project proposal on the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase III) was accepted by Taizhou DRC February 2018 construction of the Taizhou Water Supply System (Phase III) commenced.