Dace Ruklisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

Rebecca Saunders (*1967)

REBECCA SAUNDERS (*1967) 1 QUARTET 13:52 for accordion, clarinet, double-bass and piano (1998) 2 Into the Blue 12:49 To the memory of Derek Jarman for clarinet, bassoon, piano, percussion, cello and double-bass (1996) 3 Molly´s Song 3 - shades of crimson 9:07 for alto flute, viola, steel-stringed acoustic guitar, 4 radios and a music box (1995-1996) 4 dichroic seventeen for Soledad 16:13 for accordion, electric guitar, piano, two percussionists, cello and two double-basses (1998) T T: 52:299 musikFabrik Stefan Asbury Coverfoto: © Hanns Joosten 2 musikFabrik Helen Bledsoe flute Nándor Götz clarinet Alban Wesly bassoon Thomas Oesterdiekhoff percussion Arnold Marinissen percussion Ulrich Löffler piano Seth Josel acoustic guitar, electric guitar Teodoro Anzellotti accordion Tomoko Kiba violin Dominique Eyckmans viola Anton Lukoszevieze violoncello Michael Tiepold double-bass Anne Hofmann double-bass 3 Michael Struck-Schloen physikalisches Erlebnis ist für mich der Kern, aus Das heikle Gleichgewicht zwischen dem es sich entwickelt. “Man höre nur den Beginn Klang und Stille ihres 1998 in Witten uraufgeführten QUARTET für die abenteuerliche Besetzung Klarinette, Akkordeon, Die Komponistin Rebecca Saunders Klavier und Kontrabass. Die Gegensätzlichkeit ihrer Klangphysiognomien ist das Thema des Stücks: ... ein Mensch, der die Aufmerksamkeit fesselt allein durch das schreckhafte Zuschlagen des Klavierdeckels, sein Dasein ... es sind nicht Entwicklungen, die entfaltet das in wiederholten Attacken und ihren dumpfen werden, sondern „Seinszustände“, die in harten Schnitten Resonanzen im Innern des Instruments nachwirkt; aneinander gefügt sind. ...Figuren, die nichts taten, das durch Glissandi und mikrotonale Bewegungen sondern nur waren ... verhärtete Dröhnen des Kontrabasses bis hin zum Über Gertrude Steins Roman Ida „verzerrten“ (distort) Ton; die grellen Höhenregister des Akkordeons mit ihrem vulgären Vibrato und Gegen die abendländische Idee der logischen epileptischen Zittern; die expressive Zartheit der Entwicklung und formalen Integration, der die Klarinetten-Echotöne. -

![1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, Nouveaux Regards » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2006, Consulté Le 13 Août 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3445/1895-mille-huit-cent-quatre-vingt-quinze-31-2000-%C2%AB-abel-gance-nouveaux-regards-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-06-mars-2006-consult%C3%A9-le-13-ao%C3%BBt-2020-563445.webp)

1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, Nouveaux Regards » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2006, Consulté Le 13 Août 2020

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 31 | 2000 Abel Gance, nouveaux regards Laurent Véray (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/51 DOI : 10.4000/1895.51 ISBN : 978-2-8218-1038-9 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2000 ISBN : 2-913758-07-X ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Laurent Véray (dir.), 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, nouveaux regards » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 06 mars 2006, consulté le 13 août 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/1895/51 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/1895.51 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 13 août 2020. © AFRHC 1 SOMMAIRE Approches transversales Mensonge romantique et vérité cinématographique Abel Gance et le « langage du silence » Christophe Gauthier Abel Gance, cinéaste à l’œuvre cicatricielle Laurent Véray Boîter avec toute l’humanité Ou la filmographie gancienne et son golem Sylvie Dallet Abel Gance, auteur et ses films alimentaires Roger Icart L’utopie gancienne Gérard Leblanc Etudes particulières Le celluloïd et le papier Les livres tirés des films d’Abel Gance Alain Carou Les grandes espérances Abel Gance, la Société des Nations et le cinéma européen à la fin des années vingt Dimitri Vezyroglou Abel Gance vu par huit cinéastes des années vingt Bernard Bastide La Polyvision, espoir oublié d’un cinéma nouveau Jean-Jacques Meusy Autour de Napoléon : l’emprunt russe Traduit du russe par Antoine Cattin Rachid Ianguirov Gance/Eisenstein, un imaginaire, un espace-temps Christian-Marc Bosséno et Myriam Tsikounas Transcrire pour composer : le Beethoven d’Abel Gance Philippe Roger Une certaine idée des grands hommes… Abel Gance et de Gaulle Bruno Bertheuil Étude sur une longue copie teintée de La Roue Roger Icart La troisième restauration de Napoléon Kevin Brownlow 1895. -

The Physicality of Sound Production on Acoustic Instruments

THE PHYSICALITY OF SOUND PRODUCTION ON ACOUSTIC INSTRUMENTS A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tristan Rhys Williams School of Arts Brunel University September 2010 (funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council) Abstract This thesis presents practical research into sound production on instruments, working collaboratively with players, in order to build an understanding of the sounds available. I have explored the way in which instrumental technique can be extended in such a way as to function as the basis for musical material. The function of ‘figuration’ has also be brought into question, by employing seemingly primitive, residual material pushed to such a degree that it is possible to hear what happens underneath a gesture. Research in this area has been conducted by, among others, Helmut Lachenmann and Rebecca Saunders; I am drawn to the way their work highlights the tangible quality of sound. The exploration of the physicality of sound production inevitably encounters the problem that the finished work becomes a catalogue of extended techniques. My research has drawn on the work of these composers and has attempted to resolve this problem by exploring the way in which texture can suggest ‘line’ and the structural implications of sculpting self-referential material through angular and polarized divisions. This facilitates a Braille-like reading of a sound’s progress by foregrounding a non-thematic sound-surface of resonance and decay. This takes a positive and active approach to the problems of musical language, by questioning the functions and expectations put upon music. The possible solutions have been worked through in a series of works for mixed chamber ensembles, in order to investigate the palette possibilities of fusing instruments in intimate settings. -

ORPHEUS INSTITUUT GENT. Vom Hören

ORPHEUS INSTITUUT GENT. The Musician as Listener. Vom Hören. Alexander Moosbrugger im Gespräch mit Rebecca Saunders, Berlin Der Text ist Teil einer Reihe von Gesprächen mit Komponisten, entstanden im Auftrag des Orpheus Instituts Gent anlässlich des Seminars „The Musician as Listener“ (2008). 10407 Berlin, Esmarchstraße, den 15. April 2008 sowie den 7. März 2009 TEIL 1 AM Es hängen Partiturseiten an der Wand. Du gehst vom Einzelnen aus. Werden hier Klänge untereinander – ein Weißabgleich des Hörens – je nach Farbtemperatur verrechnet? RS Was ist ein Weißabgleich? AM Wenn die Kamera ein weißes Blatt Papier fokussiert, um daraus ableitend andere Farbtöne wahrnehmen, richtig bewerten zu können; sie wird auf Weiß sensibilisiert. RS Das ist interessant. Dieser Vergleich. Ich habe das noch nie so gedacht, sondern hätte von Rahmen gesprochen und davon, einen physikalischen, körperlichen Abstand zu schaffen. Weil ich die Musik, und nicht nur meine Musik, oft als etwas Bildhaftes erlebe beim Zuhören. Und irgendwie, fast aus pragmatischen Gründen, möchte ich das Stück zur Gänze, auf einmal sehen; komischerweise, wenn ich ein Stück komponiere hab’ ich das Gefühl, dass ich es noch nicht kenne, dass ich erst beispielsweise bei der Ur- oder einer späteren Aufführung wirklich das Ganze betrachte, genügend Abstand zu meinem Schaffen bekommen habe. Mir hilft das sehr, besonders im letzten Stadium beim Schreiben eines neuen Stücks, es an die Wand zu heften, weil ich empfinde, es wird dadurch gerahmt, wie man Skulpturen oder Bilder im Raum ausstellt. Diese körperliche Distanz, eine spezifische Distanziertheit, ist sehr, sehr wichtig, weswegen ich auch nicht am Computer arbeite, oder bis jetzt zumindest konnte ich noch keinen Weg finden, meine Arbeitsweise auf den Computer zu übertragen. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Yun-Peng Zhao, Constance Ronzatti, Franck Chevalier, Pierre Morlet

Yun-Peng Zhao, Constance Ronzatti, Franck Chevalier, Pierre Morlet Founded in 1996 by laureates of the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris, the Diotima Quartet has gone on to become one of the world’s most in-demand en- sembles. The name reflects the musical double identity of the group: the word Diotima is a reference to German Romantisism – Friedrich Hölderlin gave the name to the love of his life in his novel Hyperion – while it is also a nod to the music of our time, recalling Luigi Nono’s work Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima. The Diotima Quartet is honoured to partner with several of today’s major composers, such as Helmut Lachenmann, Brian Ferneyhough and Toshio Hosokawa, while also regu- larly com missioning new works from a broad range of composers, such as Tristan Murail, Alberto Posadas, Gérard Pesson, Rebecca Saunders and Pascal Dusapin. While being staunchly dedicated towards contemporary classical music, the quartet is not limited exclusively to this repertoire. In programming major classical works alongside today’s new music, their concerts offer a fresh look at works by the great composers, in particular Bartók, Debus sy and Ravel, the late quartets of Schubert and Beethoven, composers from the Viennese School, and also Janácek. The Diotima Quartet has performed widely on the international scene and at all of the major European festivals and concert series (such as at the Berlin Philharmonie; Berlin Konzerthaus; Reina Sofia, Madrid; Cité de la musique Paris; London’s Wigmore Hall and SouthBank Centre; the Vienna Konzerthaus, and so on). As well as touring regularly across the United States of America, Asia and South America, they are also artist-in-resi- dence at Paris’s Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord from 2012 to 2016. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

High-Resolution Topography of Mercury from Messenger Orbital Stereo Imaging – the Southern Hemisphere Quadrangles

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-3, 2018 ISPRS TC III Mid-term Symposium “Developments, Technologies and Applications in Remote Sensing”, 7–10 May, Beijing, China HIGH-RESOLUTION TOPOGRAPHY OF MERCURY FROM MESSENGER ORBITAL STEREO IMAGING – THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE QUADRANGLES F. Preusker 1 *, J. Oberst 1,2, A. Stark 1, S. Burmeister 2 1 German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planet. Research, Berlin, Germany – (stephan.elgner, frank.preusker, alexander.stark, juergen.oberst)@dlr.de 2 Technical University Berlin, Institute for Geodesy and Geoinformation Sciences, Berlin, Germany – (steffi.burmeister, juergen.oberst)@tu-berlin.de Commission VI, WG VI/4 KEY WORDS: Mercury, MESSENGER, Digital Terrain Models ABSTRACT: We produce high-resolution (222 m/grid element) Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) for Mercury using stereo images from the MESSENGER orbital mission. We have developed a scheme to process large numbers, typically more than 6000, images by photogrammetric techniques, which include, multiple image matching, pyramid strategy, and bundle block adjustments. In this paper, we present models for map quadrangles of the southern hemisphere H11, H12, H13, and H14. 1. INTRODUCTION Mercury requires sophisticated models for calibrations of focal length and distortion of the camera. In particular, the WAC The MErcury Surface, Space ENviorment, GEochemistry, and camera and NAC camera were demonstrated to show a linear Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft entered orbit about increase in focal length by up to 0.10% over the typical range of Mercury in March 2011 to carry out a comprehensive temperatures (-20 to +20 °C) during operation, which causes a topographic mapping of the planet. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis 9 MITWIRKENDE 10 STUDIERENDE AM TATORT KULTUR 11 VORWORT: Atelier Gespräche - Plus Kultur 13 GELEITWORT VON HEINRICH SCHMIDINGER 14 GELEITWORT VON INGRID PAUS-HASEBRINK 15 LAUDATIO VON RAINER PETERS 18 DIE GROSSEN 4 DER SALZBURG BIENNALE 2013: Zeitgenössische Musik im Zoom Karl Harb im Gespräch mit Georg Friedrich Haas und Aureliano Cattaneo Björn Gottstein im Gespräch mit Rebecca Saunders Werner Klüppelholz im Gespräch mit Vinko Globokar 30 GREGORY AHSS: Geiger und Konzertmeister Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Gregory Ahss 38 * JOHANN NESTROY: EINEN JUX WILL ER SICH MACHEN - Das Spiel zwischen Komik und Tragik Jürgen Hein: Johann NestroysEinen Jux will ersieh machen und seine tiefere Bedeutung Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Robert Pienz, Christoph Batscheider und Albert Friedl 48 EIN SOMMERNACHTSTRAUM: Verwandlungsspiel im Hof der Residenz Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Sven-Eric Bechtolf, Henry Mason und Ivor Bolton 58 OPER AKTUELL: Zeitgenössische Spielzeitpositionen am Salzburger Landestheater Dorothea Weben Der Ödipus-Mythos und seine Transformationen Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Andreas Gergen, Karolina Plickovä, Frances Pappäs, Stefan Müller und Dorothea Weber 68 BENJAMIN BRITTEN - ZUM 100. GEBURTSTAG: Ein Klassiker der Moderne Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Stephen Medcalf, Herbert Grassl, Iris Jedamski, Gottfried Franz Kasparek und Elisabeth Fuchs 76 ENGAGIERTE KUNST. POLITISCHE PERSPEKTIVEN - Taschenopernfestival 2013:Endlich Opfer Gregor Maria Hoff: Opfer-Eine prekäre theologische Bestimmung Sabine Coelsch-Foisner im Gespräch mit Brigitta Muntendorf, Thierry Bruehl, Martin Stricker und Philipp Grosser 86 CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK: DIE PILGER VON MEKKA - Ein Paradebeispiel des französisch-deutschen Kulturaustausch Daniel Brandenburg: GlucksPilger von Mekka und der französisch-deutsche Kulturaustausch im Wien des 18. -

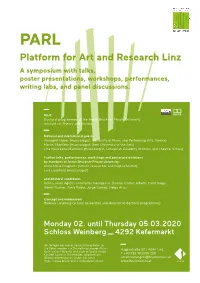

Platform for Art and Research Linz a Symposium with Talks, Poster Presentations, Workshops, Performances, Writing Labs, and Panel Discussions

PARL Platform for Art and Research Linz A symposium with talks, poster presentations, workshops, performances, writing labs, and panel discussions. Host: Doctoral programmes of the Anton Bruckner Private University Institute for Theory and History National and international guests: Annegret Huber (musicologist, University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna) Martin Skamletz (musicologist, Bern University of the Arts) Lina Navickaitė-Martinelli (musicologist, Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, Vilnius) Further talks, performances, workshops and poster presentations by members of Anton Bruckner Private University: Anne Marie Dragosits (artistic researcher and harpsichordist) Lars Laubhold (musicologist) and doctoral candidates: Dolma Jover Agulló, Constantin Georgescu, Damian Cortes Alberti, Carlo Siega, Albert Fischer, Tania Rubio, Jorge Gomez, Helga Arias Concept and moderation: Barbara Lüneburg (artistic researcher and director of doctoral programmes) Monday 02. until Thursday 05.03.2020 Schloss Weinberg 4292 Kefermarkt Wir fertigen bei dieser Veranstaltung Fotos an. Die Fotos werden zur Darstellung unserer Aktivi- Hagenstraße 57 | 4040 Linz täten auf der Website und auch in Social Media Kanälen sowie in Printmedien veröffentlicht. T +43 732 701000 280 Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter [email protected] https://www.bruckneruni.at/de/datenschutz. www.bruckneruni.at PROGRAM Monday, 02.03.2020 12.15 - 12.30 Getting Together – Welcome address 12.30 - 15.00 Technical setup and lunch 15.00 - 16.00 Váša Příhoda (1900-1960), -

Symphony Orchestrh

li>V\\V,[ VVx< BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRH ^^v f^^ •^-^ PRoGRsnnE 1(20 )| The DURABIUTY of PIANOS and the permanence of their tone quality surpass anything that has ever before been obtained, or is possible under any other conditions. This is due to the Mason & Hamlin system of manufacture, which not only carries substantial and enduring construction to its limit in every detail, but adds a new and vital principle of construc- tion—The Mason & Hamlin Tension Resonator Catalogue Mailed on Application Old Pianos Taken in Exchange MASON & HAMLIN COMPANY Established 1854 <i Opp. Institute of Technolog^y 492 Boylston Street SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON (S-MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Ticket Office, 1492 l„ ,„ TelephonesT»io«t,^«^o i Back Bay j Administration Offices, 3200 J TWENTY-NINTH SEASON, 1909-1910 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme nf % Twentieth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 1 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, APRIL 2 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A.ELLIS, MANAGER 1493 Mme. TERESA CARRENO On her tour this season will use exclusively Piano. THE JOHN CHURCH CO. NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO REPRESENTED BY G. L SCHIRMER & CO., 338 Boylston Street, Boston, Mass. 1494 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Twenty-ninth Season, 1909-1910 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor First Violins. Hess, Willy Roth, O. HofiFmann, J. Krafift, W. Concertmaster. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Second Violins. Barleben, K.