Is an MD/Phd Program Right for Me? Advice on Becoming a Physician–Scientist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMLEX-USA for Residency Program Directors

COMLEX-USA FOR RESIDENCY PROGRAM DIRECTORS COMLEX-USA Evidence–based assessment designed specifically for osteopathic medical students and residents that measures competencies required for the provision of safe and effective osteopathic medical care to patients. It is recommended but not required that COMLEX-USA Level 3 be taken after a minimum of six months in residency. The attestation process for COMLEX-USA Level 3 helps to fulfill the NBOME mission to DO candidates are not required to pass the United States protect the public, and adds value and entrustability to state licensing Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE®) to be eligible to boards and patients. Additionally, attestation provides COMLEX-USA apply to ACGME-accredited residency programs. The score reports to residency program directors and faculty. ACGME does not specify which licensing board exam(s) (i.e., COMLEX-USA, USMLE) applicants must take to be eligible COMPETENCY AND EVIDENCE-BASED DESIGN for appointment in ACGME-accredited residency programs. In 2019, COMLEX-USA completed a transition to a contemporary, two Frequently Asked Questions: Single Accreditation System decision-point, competency-based exam blueprint and evidence- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 20191 based design informed by extensive research on osteopathic physician practice, expert consensus and stakeholder surveys.3 The enhanced COMLEX-USA blueprint4 assesses measurable outcomes PATHWAY TO LICENSURE of seven Fundamental Osteopathic Medical Competency Domains5 COMLEX-USA, the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing and focuses on high-frequency, high-impact health issues and clinical Examination of the United States, is the exam series used by all presentations that affect patients. medical licensing authorities to make licensing decisions for osteopathic physicians. -

Psychiatry Residency + Phd Track

Psychiatry Residency + PhD Track Psychiatry Residency + PhD Track The Department of Psychiatry at Mount Sinai has been awarded NIMH support for this extraordinary and groundbreaking program—unique in the nation—offering a 2nd path to MD/PhD training for up to 2 residents per year. Designed for residents ready to commit to both psychiatry and research, the “PhD+” program longitudinally integrates clinical and research training over 7 years. It also offers the possibility of substantial financial advantages through NIH’s Loan Repayment Program (up to $35,000 per year for up to 6 years). As the fields of neuroscience and genetics have advanced in knowledge base and research strategies and techniques, PhD-level training may be a necessity for both effective translational research and obtaining research funding. Unfortunately, the number of psychiatrist MD/PhD researchers is small. Additionally, while the NIH has long supported Medical Scientist Training Programs, the established method of combined MD/PhD training is inefficient, in that the period of intense research and PhD completion is followed by many years of clinical training, meaning a long separation from research, a decline in research skills, a distance from the knowledge base and collaborators, and a need to retrain after residency. Our PhD+ track participates as Residency + PhD (1490400C3) in the offerings of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Psychiatry Residency Training Program, so that applicants may enter the program via the NRMP as PGY-1s. Current PGY-1s may also transfer into this track, from within our residency or from elsewhere. The PhD+ program consists of 5 components: 1) Completion of all clinical rotations/experiences required for Board Certification by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; attendance at core didactics of the Residency Program. -

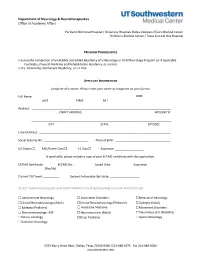

Neurology Fellowship Application

Department of Neurology & Neurotherapeutics Office of Academic Affairs Parkland Memorial Hospital / University Hospitals Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center Children's Medical Center / Texas Scottish Rite Hospital PROGRAM PREREQUISITES • Successful completion of an ACGME accredited Residency of a Neurology or Child Neurology Program (or if applicable Psychiatry, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Residency, or similar). • U.S. Citizenship, Permanent Residency, or J-1 Visa APPLICANT INFORMATION Complete all sections. Please enter your name as it appears on your license. Full Name: DOB: LAST FIRST M.I. Address: STREET ADDRESS APT/UNIT # ______________________________________________________________________________________ CITY STATE ZIP CODE Email Address: _________________________________________________________________________________ Social Security No.: ___________________________ Place of Birth: __________________________________ US Citizen ☐ EAD/Green Card ☐ J-1 Visa ☐ Expiration __________________ If applicable, please include a copy of your ECFMG certificate with this application. ECFMG Certificate: ________ ECFMG No.: ____________ Issued Date: _____________ Expiration ______________ (Yes/No) Current PGY level: __________ Desired Fellowship start date: __________________ SELECT WHICH NEUROLOGY & NEUROTHERAPEUTICS FELLOWSHIP(S) YOU ARE APPLYING FOR: ☐ Autoimmune Neurology ☐ Autonomic Disorders ☐Behavioral Neurology ☐Clinical Neurophysiology (Adult) ☐Clinical Neurophysiology (Pediatric) ☐ Epilepsy (Adult) ☐ Epilepsy (Pediatric) -

Boston Children's Hospital / Harvard Medical School Fellowship Training in Pediatric & Reproductive Environmental Health

Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School Fellowship Training in Pediatric & Reproductive Environmental Health Speaker Alan Woolf, MD, MPH, FAACT, FAAP, FACMT Director, Pediatric Environmental Health Center, Boston Children’s Hospital Director, Region 1 New England PEHSU Director, Fellowship Training Program Professor, Harvard Medical School School Physician Acknowledgments & Disclosures This material was supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and funded (in part) by the cooperative agreement FAIN: 5 NU61TS000237-05 from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Funding for this seminar was made possible (in part) by the cooperative agreement award number 1U61TS000237- 05 from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). The views expressed in written materials and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services. •The views expressed in written conference materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government •Neither EPA nor ATSDR endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in PEHSU publications. •In the past 12 months, we have had no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider(s) of commercial services discussed -

Medical Scientist Training Program

The University of Michigan MEDICAL SCIENTIST TRAINING PROGRAM General Information and Guidelines A Handbook for Fellows https://www.medicine.umich.edu/medschool/education/md-phd- program/current students/ August 2018 CONTENTS 1. MSTP Office 2. Communication 3. Academic Advising 4. I.D. and Computer Access 5. Course of Study 6. Biological Chemistry Requirement 7. Medical School Registration 8. Medical and Graduate School Grading Systems 9. Graduate School Registration 10. Research Rotations 11. Selecting a Doctoral Field and the Thesis Research Mentor 12. Graduate School Residency Requirements 13. Research Responsibility and Ethics Requirements 14. Research Phase: External Funding Sources 15. Advancement to Candidacy 16. Precandidate Year to Candidacy Transition: Funding and Insurance Issues 17. Research Phase to M3 Transition 18. M4 Year 19. Transition to Post Graduate Training, Residency 20. Dean’s Letters 21. Simultaneous Awarding of Dual Degrees 22. United States Medical Licensure Examination Step 1 and Step 2 (Clinical Knowledge and Clinical Skills) 23. Rackham Graduate School Policies 24. Medical School Policies and Procedures 25. The Fellowship Award and the Stipend Level 26. Monthly Stipend Check 27. Taxability of NRSA Stipends 28. NIH Funding Trainee Appointment Forms and Trainee Termination Notice Forms 29. Tuition Payment, Billing Procedures, and Registration 30. Travel Funds and Expense Forms 31. Health Care Insurance 32. Health Service 33. CV and Publication File 34. Individual Development Pan (IDP) 35. Vacations and Other Absences 36. MSTP Scientific Retreat 37. MSTP Seminars 38. Citizenship 39. MSTP Committees: Operating Committee (OC) and Program Activities Committee (PAC) A Handbook for MSTP Fellows MEDICAL SCIENTIST TRAINING PROGRAM General Information and Guidelines for Fellows 1. -

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts

2019‐2020 Internal Medicine Residency Handbook Table of Contents Contacts ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Compact ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Core Tenets of Residency ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Requirements ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Resident Recruitment/Appointments .............................................................................................. 9 Background Check Policy ................................................................................................................ 10 New Innovations ............................................................................................................................. 11 Social Networking Guidelines ......................................................................................................... 11 Dress Code ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Resident’s Well Being ...................................................................................................................... 13 Academic Conference Attendance ................................................................................................ -

Primer for Applying to Internal Medicine Residency Programs A

Primer for Applying to Internal Medicine Residency Programs A) Fourth-Year Schedule: • Ideally, schedule the internal medicine sub-internship during July or August in order to procure a letter of recommendation (if needed). • Alternative clinical experiences to consider in place of the sub-internship include: o Away rotations: ▪ Away rotations are NOT required for IM. The majority of students applying to IM across the country do not partake in visiting rotations. Visiting rotations are most helpful if students demonstrate a significant interest in a particular program or location. ▪ Away rotations may increase the chance of an invitation to interview at the hosting institution, but this is NOT guaranteed. ▪ Visiting subspecialty electives are preferred over visiting sub- internships, which require strong institutional systems knowledge to optimize clinical performance. o Critical Care Clerkship o Subspecialty Rotations at Cooper • IM residency interviews often start in mid-October and extend to the end of January with the majority of interviews occurring in November and December. Therefore, plan accordingly. • Schedule a more rigorous clinical experience in the spring to enhance clinical skills prior to graduation in preparation for residency. B) Timeline: C) Curriculum Vitae & ERAS Application: • Timeline: Should include all longitudinal, meaningful experiences from the first day of college until present day. • Experience Boxes: o Research Experience: ▪ Include all meaningful research at both the undergraduate and medical school level -

SAP Crystal Reports

Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey Specialties Matching Service October 2016 www.nrmp.org Requests for permission to use these data as well as questions about the content of this publication or the National Resident Matching Program data and reports may be directed to Mei Liang, Director of Research, NRMP, at [email protected]. Questions about the NRMP should be directed to Mona M. Signer, President and CEO, NRMP, at [email protected]. Suggested Citation National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey, Specialties Matching Service. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2016. Copyright © 2016 National Resident Matching Program. All rights reserved. Permission to use, copy and/or distribute any documentation and/or related images from this publication shall be expressly obtained from the NRMP. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Response rates ................................................................................................................................................. 2 All Specialties................................................................................................................................................. 3 Charts for Individual Specialties Abdominal Transplant Surgery .................................................................................................................... -

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (As of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee

ACGME Specialties Requiring a Preliminary Year (as of July 1, 2020) Transitional Year Review Committee Program Specialty Requirement(s) Requirements for PGY-1 Anesthesiology III.A.2.a).(1); • Residents must have successfully completed 12 months of IV.C.3.-IV.C.3.b); education in fundamental clinical skills in a program accredited by IV.C.4. the ACGME, the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC), or the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), or in a program with ACGME International (ACGME-I) Advanced Specialty Accreditation. • 12 months of education must provide education in fundamental clinical skills of medicine relevant to anesthesiology o This education does not need to be in first year, but it must be completed before starting the final year. o This education must include at least six months of fundamental clinical skills education caring for inpatients in family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, surgery or any surgical specialties, or any combination of these. • During the first 12 months, there must be at least one month (not more than two) each of critical care medicine and emergency medicine. Dermatology III.A.2.a).(1)- • Prior to appointment, residents must have successfully completed a III.A.2.a).(1).(a) broad-based clinical year (PGY-1) in an emergency medicine, family medicine, general surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or a transitional year program accredited by the ACGME, AOA, RCPSC, CFPC, or ACGME-I (Advanced Specialty Accreditation). • During the first year (PGY-1), elective rotations in dermatology must not exceed a total of two months. -

PGY2 Geriatric Residency Brochure

Applicant Contact Information Requirements John Roefaro, PharmD, BCGP, FASHP United States citizenship Residency Program Director PharmD degree from an ACPE- accredited college of pharmacy Email: [email protected] Completion of an ASHP- Phone: 857-303-2146 accredited PGY1 pharmacy residency Please apply via PhORCAS Active pharmacist licensure in NMS code: 672654 any US state Letter of intent Application deadline: January 18th Curriculum vitae Three letters of recommendation Our program is a partnership with including one from the program the Harvard Geriatrics Fellowship director of applicant’s PGY-1 pro- gram and the Geriatric Research Educa- PGY-2 Geriatric Complete official transcripts tion Clinical Center (GRECC) Pharmacy Application submitted via Residency Program PhORCAS Join our team! Experiences at the Brockton, Jamaica Plain, and West Roxbury campuses Program Goals The VA Boston Healthcare System offers a Core Experiences one-year ASHP-accredited PGY-2 residency in geriatrics. The purpose of this residency • Interprofessional geriatrics clinic • Palliative care program is to prepare the resident for a career in geriatric clinical pharmacy prac- • Home-based primary care tice. The graduate of this program will be • Long-term care proficient in optimization of geriatric phar- • Hospital in home macotherapy, medication reconciliation • Aging research and med management in older adults, and • Didactic learning with geriatric medicine intimately familiar with multi-disciplinary fellows through the Harvard Multicampus team assessment and management of the Geriatrics Fellowship older patient. The resident will receive comprehensive, Elective Experiences Resident Positions intense, and individualized training in as- • Primary care pharmacy clinic, with pharma- • There is one position available for the pects of geriatrics from dedicated, passion- cist as the provider with prescriptive privi- PGY2 geriatric pharmacy program. -

School of Medicine and Dentistry Student Handbook

University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Student Handbook Updated: September 21, 2021 1 | Page INTRODUCTION This official student handbook has been compiled to inform students about institutional policies as well as to identify many services and resources that may be of value during their training at Rochester. The policies and guidelines of the School are dynamic – constantly being improved through the efforts of students, faculty, and administration. We publish the official handbook in a web-based format and send students periodic updates. All policies are subject to improvement and revision at any time. We hope students find these materials to be useful. Should students have any comments, concerns, or questions, they should contact their Advisory Dean or any staff member in the Student Services Center. Sincerely, David R. Lambert, M.D. Senior Associate Dean for Medical Student Education 2 | Page Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 I. ADMISSIONS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 FALSIFICATION OF ADMISSIONS INFORMATION .................................................................................................................... 8 Academic, Behavioral and Professionalism Expectations of Accepted -

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What Is Geriatric Medicine?

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What is Geriatric Medicine? Geriatrics is the branch of medicine that focuses on health promotion, prevention, and diagnosis and treatment of disease and disability in older adults. In recent surveys, geriatricians are among the most satisfied physicians in terms of their choice of specialty. Geriatrics offers a wide diversity of career options and is a clinically and intellectually rewarding discipline given the medical complexity of older adults. Geriatricians reap the rewards of making a difference in a patient’s level of independence, well- being and quality of life. With the rapid growth of the older population in the United States, there is a pressing demand for physicians with specialized training in geriatrics. ama-assn.org/specialty/geriatric-medicine The Birth of “Geriatric” Medicine • In 1909, Austrian born physician, Ignatz Leo Nascher coined the term “geriatrics” for care of the elderly, explaining, “Geriatrics, from geras, old age, and iatrikos, relating to the physician, is a term I would suggest as an addition to our vocabulary, to cover the same field in old age that is covered by the term pediatrics in childhood, to emphasize the necessity of considering senility and its disease apart from maturity and to assign it a separate place in medicine.” • Until Nascher’s time, older adults were not treated differently or in different ways than other adult patients. Social forces came into play in the period during WWI and WWII that both necessitated and facilitated long-term care for the elderly: The number of elderly people began to increase due to improvements in economic conditions and medicine.