Redesigning Provider Payments to Reduce Long Term Cost Paper.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grimes County Bride Marriage Index 1846-1916

BRIDE GROOM DATE MONTH YEAR BOOK PAGE ABEL, Amelia STRATTON, S. T. 15 Jan 1867 ABSHEUR, Emeline DOUTMAN, James 21 Apr 1870 ADAMS, Catherine STUCKEY, Robert 10 Apr 1866 ADAMS, R. C. STUCKEY, Robert 24 Jan 1864 ADKINS, Andrea LEE, Edward 25 Dec 1865 ADKINS, Cathrine RAILEY, William Warren 11 Feb 1869 ADKINS, Isabella WILLIS, James 11 Dec 1868 ADKINS, M. J. FRANKLIN, F. H. 24 Jan 1864 ADLEY, J. PARNELL, W. S. 15 Dec 1865 ALBERTSON, R. J. SMITH, S. V. 21 Aug 1869 ALBERTSON, Sarah GOODWIN, Jeff 23 Feb 1870 ALDERSON, Mary A. LASHLEY, George 15 Aug 1861 ALEXANDER, Mary ABRAM, Thomas 12 Jun 1870 ALLEN, Adline MOTON, Cesar 31 Dec 1870 ALLEN, Nelly J. WASHINGTON, George 18 Mar 1867 ALLEN, Rebecca WADE, William 5 Aug 1868 ALLEN, S. E. DELL, P. W. 21 Oct 1863 ALLEN, Sylvin KELLUM, Isaah 29 Dec 1870 ALSBROOK, Leah CARLEY, William 25 Nov 1866 ALSTON, An ANDERS, Joseph 9 Nov 1866 ANDERS, Mary BRIDGES, Taylor 26 Nov 1868 ANDERSON, Jemima LE ROY, Sam 28 Nov 1867 ANDERSON, Phillis LAWSON, Moses 11 May 1867 ANDREWS, Amanda ANDREWS, Sime 10 Mar 1871 ARIOLA, Viney TREADWELL, John J. 21 Feb 1867 ARMOUR, Mary Ann DAVIS, Alexander 5 Aug 1852 ARNOLD, Ann JOHNSON, Edgar 15 Apr 1869 ARNOLD, Mary E. (Mrs.) LUXTON, James M. 7 Oct 1868 ARRINGTON, Elizabeth JOHNSON, Elbert 31 Jul 1866 ARRINGTON, Martha ROACH, W. R. 5 Jan 1870 ARRIOLA, Mary STONE, William 9 Aug 1849 ASHFORD, J. J. E. DALLINS, R. P. 10 Nov 1858 ASHFORD, L. A. MITCHELL, J. M. 5 Jun 1865 ASHFORD, Lydia MORRISON, Horace 20 Jan 1866 ASHFORD, Millie WRIGHT, Randal 23 Jul 1870 ASHFORD, Susan GRISHAM, Thomas C. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Gloria Rognlie

EAST TEXAS CHAPTER MASTER NATURALISTS National Fishing & Boating Week and Texas Fishing Week June 2 -10, 2012 Our Member of President’s Mary Ann’s Do the Month: Corner Class of 2012 Snake Tale Gloria Rognlie Yo u K no w ? completes training Check out Sea Turtle classes Help Save Our Endangered Sea the links Turtles Page 9 Page 2 If We Don’t We’ll Page 5 - 6 Lose Them Ongoing volunteer Page 3 Did She Release It? Forever opportunities: Page 4 Page 7 -8 Page 9 June 2012 Newsletter !Volume 8 - Issue 6 East Texas Chapter Monthly Meeting May 24 A BIG Thank You to the presents: Michael Banks, Co-Director of the Friends of the Neches River. Native Plant Society of Texas Tyler Chapter His presentation will discuss the Friends of the Neches River and what they are trying to for the new plantings at accomplish. The Nature Center - Tyler You can research the Friends of the Neches River or visit their facebook site: https://www.facebook.com/ pages/Friends-of-the-Neches-River/ Michael Banks with a 111473105531196?sk=info and get more nice Neches River bass. background information. It is my understanding this group was formed to prevent the Neches River from being dammed to form a water reservoir to supply water to the Dallas area. The establishment of the Neches River National Wildlife Refuge is being heralded as one of the recent major conservation victories in Texas. They are concerned about loss of hardwood Michael Banks the Co- bottomland and the plants and animals that reside Director of the Friends of there. -

A C B D Dd E

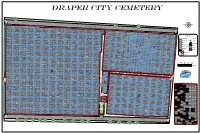

Draper City Cemetery G a t ÍÎ e A_15A_3 A_15A_4 A_30A_3 A_30A_4 A_45A_2 A_45A_1 A_75A_2a A_15A_2 A_15A_1 A_60A_2 A_60A_1 A_30A_2 A_30A_1 Brown, Ernest NephBirown, Vonda Lawreatha Jensen, Lauris Nielsen, Soren ^ Brown, Child Brown, Child A_75A_2b A_75A_1 Jensen, Karen A_15_5 A_15_6 A_30_6 A_45_5 A_90A_2 C A_30_5 A_45_6 emete Cutler, Patricia F A_60_5 ry Ro A_60_6 ad A_75_5 Marlin, Dayna Stringfellow Pearson, Ernest Alvin Pearson, William Q. A_75_6 Barron, Kainalu Alolike' Carl Ray Brown, Child Brown, Child A_105_5 A_105_6 ÍÎ Orgill, Hazel Orgill, Ruhama A_90_6 A_120_5 A_15_10 A_30_10 A_90_5 A_135_5 A_135_6 A_45_10 Pederson, Lynette (Infant) Cutler, Carma Hill, Ann A_120_6 A_15_4 A_60_10 A_75_10 Unknown, Poor Lot Unknown, Poor Lot A_15_7 A_30_4 A_30_7 A_45_4 A_90_10 Cutler, Ben A_45_7 A_60_4 A_60_7 A_105_10 Stringfellow, Elnora DM.arlin, Jackson Everett A_75_4 A_75_7 A_120_10 A_135_10 A_150_6 Pearson, Sarah AllenPearson, James Oscar Brown, Child A_150_5 A_165_5 A_165_6 ÍÎ ^ Brown, Child Branford, Ona A_90_4 A_90_7 A_105_7 A_120_4 For Covington, Anne A_195_5 Orgill, Ivan A_180_5 ^ A_105_4 A_135_4 A_135_7 Child Soggs, Unknown A_180_6 A_199_5 A_30_8a A_30_8b Cutler, Clinton Louis Hill, Thomas A_120_7 Ellis, Everet A_195_6 A_199_6 A_15_3 A_15_8 A_30_3 Unknown, Poor Lot Unknown, Poor Lot A_165_10 Peterson, Cathy Landeen, Marjorie Evelyn C_7_5 StringfeSltloriwng, fBeallboyw, Jana Maxine A_45_3 A_45_8 A_75_8a A_90_3a A_150_4 A_180_10 Sparks, Blanche MayHarwood, Margaret G. A_60_3 A_60_8 A_150_7 A_165_7 Stringfellow, George S. A_30_8c Pearson, Henry A_75_3 Orgill, Infant S.W. A_165_4 A_180_4 Soderberg, Ardella M. C_7_6 C_14_5 µ Whetman, Velora Ruth Fitzgerald, Isaac M. Greenwood, Gene CalvCinovington, Justin Max A_195_4 C_14_6 e Cutler, Elizabeth Enniss BrownBrown, Child Orgill, Mary Collins Crapo A_90_8 A_105_3 A_105_8 Soggs, Mrs. A_180_7 A_199_4 A_199_7 for Gordon, Angie A_15_9 Orgill, Hannah Inez Stringfellow A_75_8b A_90_3b A_120_3 A_120_8 A_135_3 Allen, Pauline E. -

An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline

SPECIAL FEATURE Clinical Practice Guideline Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline Cynthia A. Stuenkel, Susan R. Davis, Anne Gompel, Mary Ann Lumsden, M. Hassan Murad, JoAnn V. Pinkerton, and Richard J. Santen University of California, San Diego, Endocrine/Metabolism (C.A.S.), La Jolla, California 92093; Monash University, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine (S.R.D.), Melbourne 03004, Australia; Universite´ Paris Descartes, Hoˆ pitaux Universitaires Port Royal-Cochin Unit de Gyne´ cologie Endocrnienne (A.G.), Paris 75014, France; University of Glasgow School of Medicine (M.A.L.), Glasgow G31 2ER, Scotland; Mayo Clinic, Division of Preventive Medicine (M.H.M.), Rochester, Minnesota 55905; University of Virginia, Obstetrics and Gynecology (J.V.P.), Charlottesville, Virginia 22908; and University of Virginia Health System (R.J.S.), Charlottesville, Virginia 22903 Objective: The objective of this document is to generate a practice guideline for the management and treatment of symptoms of the menopause. Participants: The Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause Task Force included six experts, a methodologist, and a medical writer, all appointed by The Endocrine Society. Evidence: The Task Force developed this evidenced-based guideline using the Grading of Recom- mendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system to describe the strength of recommendations and the quality of evidence. The Task Force commissioned three systematic reviews of published data and considered several other existing meta-analyses and trials. Consensus Process: Multiple e-mail communications, conference calls, and one face-to-face meet- ing determined consensus. Committees of The Endocrine Society, representatives from endorsing societies, and members of The Endocrine Society reviewed and commented on the drafts of the guidelines. -

Special Anniversary Issue Moran’S Mexican Debut Is up and Running Milestones

The Magazine of Volume 63 Moran Towing Corporation November 2010 Special Anniversary Issue Moran’s Mexican Debut Is Up and Running Milestones 34 miles north of Ensenada, tug’s motion, thereby preventing snap-loads and Mexico, in Pacific waters breakage. This enables the tug to perform opti- just off the Mexican Baja, mally, at safe working loads for the hawser, under Moran’s SMBC joint ven- a very wide range of sea state and weather condi- ture (the initials stand for tions. The function is facilitated by sensors that Servicios Maritimos de Baja continuously detect excess slack or tension on the California) has been writ- line, and automatically compensate by triggering 15ing a new chapter in the company’s history. either spooling or feeding out of line in precise- SMBC, a joint venture with Grupo Boluda ly the amounts necessary to maintain a pre-set Maritime Corporation of Spain, has been operat- standard of tension. ing at this location since 2008. It provides ship To a hawser-connected tug and tanker snaking assist, line handling and pilot boat services to over the crests of nine-foot swells, this equipment LNG carriers calling at Sempra LNG’s Energia is as indispensable as a gyroscope is to a rocket; its Costa Azul LNG terminal. stabilizing effect on the motion of the lines and SMBC represents a new maritime presence in vessels gives the mariners complete control. North American Pacific coastal waters. Each of its As part of this capability, upper and lower load tugs bears dual insignias on its stacks: the Moran ranges can be digitally selected and monitored “M” and Boluda’s “B”. -

Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No

Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No. MA-64 Vineyard Haven Martha's Vineyard Dukes County Li A ^ ^ Massachusetts ' l PHOTOGRAPHS REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, DC 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Pilot Schooner ALABAMA (ALABAMIAN) HAER No. MA-64 Rig/Type of Craft: 2-masted schooner; mechanically propelled, sail assisted Trade: pilot vessel Official No.: 226177 Principle Dimensions: Length (overall): 88.63' Gross tonnage: 70 Beam: 21.6* Net tonnage: 35 Depth: 9.7' Location: moored in harbor at Vineyard Haven Martha's Vineyard Dukes County Massachusetts Date of Construction: 1925 Designer: Thomas F. McManus Builder: Pensacola Shipbuilding Co., Pensacola, Florida Present Owner: Robert S. Douglas Box 429 Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts 02568 Present Use: historic vessel Significance: ALABAMA was designed by Thomas F. McManus, a noted fi: schooner and yacht designer from Boston, Massachusetts. She was built during the final throes of the age of commercial sailing vessels in the United States and is one of a handful of McManus vessels known to survive. Historian: W. M. P. Dunne, HAER, 1988. Schooner Alabama HAER No. MA-64 (Page 2) TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue 3 The Colonial Period at Mobile 1702-1813 5 Antebellum Mobile Bar Pilotage 10 The Civil War 17 The Post-Civil War Era 20 The Twentieth Century 25 The Mobile Pilot Boat Alabama, Ex-Alabamian, 1925-1988 35 Bibliography 39 Appendix, Vessel Documentation History - Mobile Pilot Boats 18434966 45 Schooner Alabama HAER No. MA-64 (Page 3) PROLOGUE A map of the Americas, drawn by Martin Waldenseemuller in 1507 at the college of St. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Descendants of Epenetus Smith

Descendants of Epenetus Smith Generation No. 1 5 4 3 2 1 1 1. EPENETUS SMITH (HENRY , ZACHARIAH , THOMAS , NICHOLAS SEVERNSMITH) was born 10 Nov 1766 in Huntington, Suffolk Co., LI, NY, and died 24 May 1830 in Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY2. He married 3 ELIZABETH SMITH 17 Nov 1792 in Rev Joshua Hartt, Smithtown, LI, NY , daughter of EPENETUS SMITH and 4 SUSANNAH SCUDDER. She was born Abt. 1771 in Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY , and died 09 Feb 1858 in Huntington, Suffolk Co., LI, NY5. More About EPENETUS SMITH: Burial: Old Huntington Burial Ground More About ELIZABETH SMITH: Burial: Old Huntington Burial Ground Children of EPENETUS SMITH and ELIZABETH SMITH are: 2. i. MARIA6 SMITH, b. 24 Nov 1793, Centerport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 22 Dec 1884, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY. 3. ii. SUSAN SCUDDER SMITH, b. 22 Aug 1798, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 25 Nov 1875, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY. iii. EZRA B SMITH, b. Abt. 1800, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 02 Dec 1826, Huntington, Suffolk Co., LI, NY5. More About EZRA B SMITH: Burial: Old Huntington Burial Ground6 iv. TREADWELL SMITH, b. Abt. 1803, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 08 Apr 1830, Huntington, Suffolk Co., LI, NY7. More About TREADWELL SMITH: Burial: Old Huntington Burial Ground8 4. v. HENRY CHICHESTER SMITH, b. 05 Aug 1806, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 28 Aug 1858, Huntington, Suffolk Co., LI, NY. 5. vi. BREWSTER H SMITH, b. 15 Aug 1809, Northport, Suffolk Co., LI, NY; d. 03 Feb 1888, North Hempstead, Queens Co., LI, NY. -

Magazine of the International Women Pilots, the Ninety-Nines Inc. August

AE MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS Magazine of the EVELYN BRYAN JOHNSON, A Dynamic 99 International Women Pilots, Excellent Educators—Erickson & Bartels The Ninety-Nines Inc. NIFA SAFECON ’91 August/September 1991 Women of OSHKOSH ’91, a photo essay THE CONVENTION, ORLANDO ’91 AOPA EXPO ’91 N ew O rlea n s x New Orleans Convention Center V- O c t. 23-26,1991y .4 •• 'I'he 1991 AOPA convention and trade exhibit .. promises to be the biggest and best ever. We’ve added a day, extended exhibit hours and can help ;s you cut fuel and travel expenses. Nowhere else will you find so much general aviation information packed into one place. There’s a static aircraft display too. And an impressive seminar program covering a host of topics important to each and every pilot. Our new Share-A-Flight Service helps pilots travel together and cut fuel costs. Plus there are special attendance and room discounts. But only if you register early. fi w . Don’t let this once-a-year aviation opportunity fly ‘ by. Call for your complete registration package now. '. \- • : • • • 4 C • 'j ' • ' V • • : I t o * AIRCRAFT OWNERS AND PILOTS ASSOCIATION Call Toll Free: 1-800-USA-AOPA Ask For Details About AOPA’s Exclusive Share-A-Flight Service. YOUR LETTERS From Faith B. Richards. E. Orange, NJ: NINETY-NINE News “I enjoyed Mary Lou Neale’s story about my Magazine of the Russian friends, Galina and Ludmilla. There International Women Pilots, is one discrepancy I wish to bring to your The Ninety-Nines Inc. attention. The 1st woman to set world Heli August/September 1991 copter records was accomplished in 1961 by Vol. -

Blessed Christmas Peace Prayer

929 Pearl Road Brunswick, Ohio 44212 330.460.7300 www.StAmbrose.us Blessed Christmas This is the 60th Anniversary of our parish community... Jesus Christ... the 60th time we have come together on this most THE GIFT OF holy night to celebrate the birth of our Savior – Jesus Christ. We come together in prayer and worship to celebrate the perfect gift of God’s love in Jesus Christ. SAINT AMBROSE PARISH If you do a google search of key events in 1957, you will CHRISTMAS 2017 find that many of the same issues we are facing today were happening back then. The world order was changing and people were flocking to the Church to “Let us follow the star of inspiration pray for peace and God’s protection in their families. and divine attraction, which calls us Throughout all these years, Saint Ambrose has been a to the crib, and let us go thither to special place for people of every age to come together adore and love the child Jesus and offer in faith and prayer. Our community has always been committed to the teaching of the Gospel and strong ourselves to him.” family values. The community has always looked to our -St. Clare of Assisi church for help, hope and comfort in their times of need. This Christmas, we give thanks to God for all of our loved ones who have set such a strong foundation for our families and for our parish family. We renew our commitment to pray for peace and hold firm to the values of faith and family. -

On Blue Water, the Eagle Flies

The Magazine of Volume 65 Moran Towing Corporation March 2 015 On Blue Water, the Eagle Flies Moran’s Tom Craighead Sails aboard the Coast Guard’s Celebrated Tall Ship PHOTO CREDITS Page 37: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz Cover: Petty Officer 2nd Class Walter Shinn, USCG Atlantic Area Page 38: Operational areas of the bilateral symmetry of the human Inside Front Cover: John Snyder, body plan, by Iñaki Otsoa, marinemedia.biz Licensed under CC by 3.0 via Page 2: Courtesy of the Chamber Wikimedia Commons, of Shipping of America http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki Pages 4–6, 8 (top), and 9: Page 41: John Snyder, John Snyder, marinemedia.biz marinemedia.biz Page 8 (bottom): Page 47: Courtesy of National Portbeaumont, by R. Rothenberger, Oceanographic and Atmospheric Licensed under CC by 3.0 via Administration (NOAA) Wikimedia Commons, Pages 49, 51 and 53: Reprinted http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki by permission of Proceedings, a Pages 11, 12 (bottom), and 14–17: publication of the U.S. Naval Tom Craighead, Vice President/Gen- Intelligence Institute eral Manager, Moran Jacksonville Page 56: 123RF.com Page 12 (top): Petty Officer 2nd Pages 57–59: John Snyder, Class Walter Shinn, USCG marinemedia.biz Atlantic Area Page 61: Courtesy of Sophie Page 18 (both photos): Petty Schleicher and The Maritime Officer 2nd Class Walter Shinn, Studies Program of Williams USCG Atlantic Area College and Mystic Seaport Pages 20 and 22–26: John Snyder, Page 62: Caroline Baviello marinemedia.biz Inside Back Cover: John Snyder, Page 28: Courtesy of Molinos marinemedia.biz de Puerto Rico, a division of Ardent Mills Back Cover: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz Pages 29–31: Bruce Edwards, trvmedia.com All others: Moran Archives or public domain Pages 32–33 and 35: Courtesy of Coastal and Ocean Resources Inc.