Journal Clothing and Textiles Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineers Week Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials

Engineers Week Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials Classroom Resource Booklet Developed for 1 Engineers Week - Classroom Resource Booklet DPSM/ESERO Framework for Inquiry THEME Overall theme Strand: CURRICULUM Maths: Strand Unit: Curriculum Objectives: Skills Development: Considerations ENGAGE for inclusion THE TRIGGER WONDERING EXPLORING INVESTIGATE CONDUCTING THE SHARING: INTERPRETING STARTER QUESTION PREDICTING INVESTIGATION THE DATA / RESULTS TAKE THE NEXT STEP APPLYING LEARNING MAKING CONNECTIONS THOUGHTFUL ACTIONS REFLECTION 2 Engineers Week - Classroom Resource Booklet DPSM/ESERO Framework for Inquiry THEME ENGINEERS WEEK 2021 – ENGINEERING DESIGN Strand: Living Things, Materials; Energy and Forces; Environmental Awareness and Care. Strand Unit: Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials. CURRICULUM Curriculum Objectives: Explore and investigate how people move; Understand how materials may be used in construction; Explore the effect of friction on movement through experimenting with toys and objects on various surfaces. Skills Development - Working Scientifically: Questioning, Observing, Predicting, Analysing, Investigating, Recording and Communicating; Design, plan and carry out simple investigations; Designing and Making: Exploring, Planning, Making, Evaluating; Work collaboratively to create a design proposal; Communicate and evaluate the design plan using sketches, models and information and communication technologies; Using small models and/or sketches showing measurements and materials required; -

Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 087 919 CB 001 018 AUTHOR Hayes, Philip TITLE Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C. Vocational Education Media Center.; South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. Office of Vocational Education. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 100p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$4.20 DESCRIPTORS Business Education; Clothing Design; *Distributive Education; *Guides; High School Curriculum; Manuals; Student Developed Materials; *Student Projects IDENTIFIERS *Career Awareness; South Carolina ABSTRACT This semester-length guide for high school distributive education students is geared to start the student thinking about the vocation he would like to enter by exploring one area of interest in marketing and distribution and then presenting the results in a research paper known as an area of distribution manual. The first 25 pages of this document pertain to procedures to follow in writing a manual, rules for entering manuals in national Distributive Education Clubs of America competition, and some summary sheet examples of State winners that were entered at the 25th National DECA Leadership Conference. The remaining 75 pages are an example of an area of distribution manual on "How Fashion Changes Relate to Fashion Designing As a Career," which was a State winner and also a national finalist. In the example manual, the importance of fashion in the economy, the large role fashion plays in the clothing industry, the fast change as well as the repeating of fashion, qualifications for leadership and entry into the fashion world, and techniques of fabric and color selection are all included to create a comprehensive picture of past, present, and future fashion trends. -

The Developing Years 1932-1970

National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNIFORMS The Developing Years 1932-1970 Number 5 By R. Bryce Workman 1998 A Publication of the National Park Service History Collection Office of Library, Archives and Graphics Research Harpers Ferry Center Harpers Ferry, WV TABLE OF CONTENTS nps-uniforms/5/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016 http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-uniforms/5/index.htm[8/30/18, 3:05:33 PM] National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 (Introduction) National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 INTRODUCTION The first few decades after the founding of America's system of national parks were spent by the men working in those parks first in search of an identity, then after the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 in ironing out the wrinkles in their new uniform regulations, as well as those of the new bureau. The process of fine tuning the uniform regulations to accommodate the various functions of the park ranger began in the 1930s. Until then there was only one uniform and the main focus seemed to be in trying to differentiate between the officers and the lowly rangers. The former were authorized to have their uniforms made of finer material (Elastique versus heavy wool for the ranger), and extraneous decorations of all kinds were hung on the coat to distinguish one from the other. The ranger's uniform was used for all functions where recognition was desirable: dress; patrol (when the possibility of contact with the public existed), and various other duties, such as firefighting. -

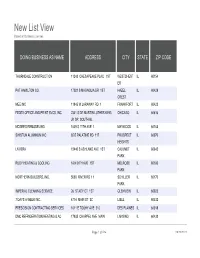

New List View Based on Business Licenses

New List View Based on Business Licenses DOING BUSINESS AS NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE THORNDALE CONSTRUCTION 11243 CHESAPEAKE PLAC 1ST WESTCHEST IL 60154 ER PAT HAMILTON CO. 17021 S MAGNOLIA DR 1ST HAZEL IL 60429 CREST MEE INC 11845 W LARAWAY RD 1 FRANKFORT IL 60423 FEDEX OFFICE AND PRINT SVCS, INC. 2301 S DR MARTIN LUTHER KING CHICAGO IL 60616 JR DR SOUTH BL MCGEE'S REMODELING 1009 S 11TH AVE 1 MAYWOOD IL 60153 SWISTUN ALUMINUM INC 65 E PALATINE RD 117 PROSPECT IL 60070 HEIGHTS LA'VERA 12440 S ASHLAND AVE 1ST CALUMET IL 60643 PARK RILEY HEATING & COOLING 16 N 9 TH AVE 1ST MELROSE IL 60160 PARK NORTHERN BUILDERS, INC. 5060 RIVER RD 1 1 SCHILLER IL 60176 PARK IMPERIAL CLEANING SERVICE 26 STACY CT 1ST GLENVIEW IL 60025 7 DAYS A WEEK INC. 4714 MAIN ST 3C LISLE IL 60532 PRESCISION CONTRACTING SERVICES 1011 E TOUHY AVE 210 DES PLAINES IL 60018 DMC REFRIGERATION HEATING & AC 17935 CHAPPEL AVE MAIN LANSING IL 60438 Page 1 of 524 09/28/2021 New List View Based on Business Licenses LICEN SE LICENSE CODE APPLICATION TYPE DATE ISSUED STATU S 1010 RENEW 08/24/2009 AAI 1010 ISSUE 04/12/2006 AAI 1010 RENEW 03/13/2015 AAI 1010 RENEW 01/22/2009 AAI 1011 RENEW 11/24/2008 AAI 1010 RENEW 02/28/2008 AAI 1315 RENEW 11/29/2012 AAI 1011 RENEW 02/22/2007 AAI 1010 RENEW 04/07/2016 AAI 1010 RENEW 05/17/2010 AAI 1010 RENEW 04/07/2016 AAI 1010 C_LOC 07/02/2013 AAI 1010 RENEW 06/08/2011 AAI Page 2 of 524 09/28/2021 New List View Based on Business Licenses HOLLAWAY MEYER'S INC 950 165TH ST 1 HAMMOND IN 46324 STRERLING ELEVATOR SERVICE CO 2510 E DEMPSTER 208 DES PLAINES IL 60016 360NETWORKS (USA) INC. -

Hagakure: Book of the Samurai

Hagakure: Book of the Samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo 2nd version, revised January 2005 Contents About this ebook iii Preface iv 1 Although it stands 1 2 It is said that 52 3 Lord Naoshige once said 77 4 When Nabeshima Tadanao 79 5 No text 82 6 When Lord Takanobu 83 i 7 Narutomi Hyogo said 90 8 On the night of the thirteenth day 104 9 When Shimomura Shoun 124 10 There was a certain retainer 134 11 In the “Notes on Martial Laws” 151 12 Late night idle talk 166 About this ebook This is the first release of the book and Lapo would appre- ciate if you inform him of any spelling or typographic error via email at [email protected]. Acknowledgement Lapo expresses his gratitude for spelling corrections to: Oliver Oppitz. iii Preface Hagakure is the essential book of the Samurai. Written by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, who was a Samurai in the early 1700s, it is a book that combines the teachings of both Zen and Con- fucianism. These philosophies are centered on loyalty, devotion, purity and selflessness, and Yamamoto places a strong emphasis on the notion of living in the present moment with a strong and clear mind. The Samurai were knights who defended and fought for their lords at a time when useful farming land was scarce and in need of protection. They believed in duty, and gave themselves completely to their masters. The Samurai believed that only after transcending all fear could they obtain peace of mind and yield the power to serve their masters faithfully and loyally even iv in the face of death. -

Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those

067_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 4/30/08 3:22 PM Page 67 Singular/Plural Adjectives This/That/These/Those • Clothing • Price Tags • Colors • Clothing Sizes • Shopping for Clothing • Clothing Ads • Money • Store Receipts VOCABULARY PREVIEW 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1. shirt 6. jacket 11. pants 2. coat 7. suit 12. jeans 3. dress 8. tie 13. pajamas 4. skirt 9. belt 14. shoes 5. blouse 10. sweater 15. socks 67 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 68 Clothing 8 2 1 9 3 11 10 4 12 5 6 13 14 7 15 20 21 16 25 24 22 17 26 18 19 23 27 1. shirt 8. earring 15. hat 21. suit 2. tie 9. necklace 16. coat 22. watch 3. jacket 10. blouse 17. glove 23. umbrella 4. belt 11. bracelet 18. purse / 24. sweater 5. pants 12. skirt pocketbook 25. mitten 6. sock 13. briefcase 19. dress 26. jeans 7. shoe 14. stocking 20. glasses 27. boot 68 068_075_SBSPLUS1_CH08.qxd 5/1/08 5:01 PM Page 69 Shirts Are Over There SINGULAR/PLURAL* s z IZ a shirt – shirts a tie – ties a dress – dresses a coat – coats an umbrella – umbrellas a watch – watches a hat – hats a sweater – sweaters a blouse – blouses a belt – belts a necklace – necklaces A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. A. Excuse me. I’m looking for a shirt. I’m looking for a tie. I’m looking for a dress. B. Shirts are over there. B. Ties are over there. -

Lesser Escape Artists

Ron MacLean Copyright 2015 [email protected] 617.512.7763 Lesser Escape Artists 1. There's blood in the end. I'm not going to toy with your emotions by keeping you in the dark about that. He was, after all, an unusual rabbit. (Don't worry, an assistant meat man said, that critter could talk his way out of anything.) There we stood: she, possibly pregnant, rabbit in hand; butcher, cleaver dangling, hand on skinned haunch (nanny or billy not clear); me, distracted by movement in a back shop corner. It was your standard butcher shop: glass case, filigreed walls, wood chopping block (waist-high, double-wide), the small stage where the Pips would later perform. The metallic tang of raw meat. Behind the counter, shelves reached to the ceiling, packed with jars and cans (kidney pies, pickled pig parts). We failed to see the goat lurking in the shadows. What I learned: what you escape to as important as what you escape from. But first, the rabbit. We knew nothing of breeds. Suspected we might be breeders ourselves (what got us into this). Five-and-a-half pounds, deep red coat, wild ears, muscular flank, well-rounded hind quarters. We didn't appreciate what we had, even apart from his ability to wax philosophical. ("Desire fractures us all," said the rabbit, about to go on the chopping block.) 2. Not even the butcher wanted a blind rabbit. "What am I supposed to do with that?" he asked, cleaver in hand. Tall and thin, he wore a white apron over a crisp white shirt. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Thomas Gaubatz All rights reserved ABSTRACT Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz This dissertation examines the ways in which the narrative fiction of early modern (1600- 1868) Japan constructed urban identity and explored its possibilities. I orient my study around the social category of chōnin (“townsman” or “urban commoner”)—one of the central categories of the early modern system of administration by status group (mibun)—but my concerns are equally with the diversity that this term often tends to obscure: tensions and stratifications within the category of chōnin itself, career trajectories that straddle its boundaries, performative forms of urban culture that circulate between commoner and warrior society, and the possibility (and occasional necessity) of movement between chōnin society and the urban poor. Examining a range of genres from the late 17th to early 19th century, I argue that popular fiction responded to ambiguities, contradictions, and tensions within urban society, acting as a discursive space where the boundaries of chōnin identity could be playfully probed, challenged, and reconfigured, and new or alternative social roles could be articulated. The emergence of the chōnin is one of the central themes in the sociocultural history of early modern Japan, and modern scholars have frequently characterized the literature this period as “the literature of the chōnin.” But such approaches, which are largely determined by Western models of sociocultural history, fail to apprehend the local specificity and complexity of status group as a form of social organization: the chōnin, standing in for the Western bourgeoisie, become a unified and monolithic social body defined primarily in terms of politicized opposition to the ruling warrior class. -

Aja 11(1-2) 2013

Alaska Journal of Anthropology Volume 11, Numbers 1&2 2013 Alaska Journal of Anthropology © 2013 by the Alaska Anthropological Association: All rights reserved. ISSN 1544-9793 editors alaska anthropological association Kenneth L. Pratt Bureau of Indian Affairs board of directors Erica Hill University of Alaska Southeast Rachel Joan Dale President research notes Jenya Anichtchenko Anchorage Museum Anne Jensen UIC Science April L. G. Counceller Alutiiq Museum book reviews Robin Mills Bureau of Land Amy Steffian Alutiiq Museum Management Molly Odell University of Washington correspondence Jeffrey Rasic National Park Service Manuscript and editorial correspondence should be sent (elec- tronically) to one or both of the Alaska Journal of Anthropology other association officials (AJA) editors: Vivian Bowman Secretary/Treasurer Kenneth L. Pratt ([email protected]) Sarah Carraher Newsletter Editor University of Alaska Erica Hill ([email protected]) Anchorage Rick Reanier Aurora Editor Reanier & Associates Manuscripts submitted for possible publication must con- form with the AJA Style Guide, which can be found on membership and publications the Alaska Anthropological Association website (www. For subscription information, visit our website at alaskaanthropology.org). www.alaskaanthropology.org. Information on back issues and additional association publications is available on page 2 of the editorial board subscription form. Please add $8 per annual subscription for postage to Canada and $15 outside North America. Katherine Arndt University of Alaska Fairbanks Don Dumond University of Oregon Design and layout by Sue Mitchell, Inkworks Max Friesen University of Toronto Copyediting by Erica Hill Bjarne Grønnow National Museum of Denmark Scott Heyes Canberra University Susan Kaplan Bowdoin College Anna Kerttula de Echave National Science Foundation Alexander King University of Aberdeen Owen Mason GeoArch Alaska Dennis O’Rourke University of Utah Katherine Reedy Idaho State University Richard O. -

Officers' Uniforms and Gear

officer’s guide Lesson 3: Officers’ uniforms and gear Reference: The Officer’s Guide, 1944 edition; AR 600-40; FM 21-15. Study assignment: Lesson text, attached. What the uniform signifies “The wearing of the prescribed uniform identifies the officer or soldier as a member of the Army of the United States.”1 It identifies the wearer as one who has sworn to defend his nation against a determined enemy, even at the risk of life; the details of the uniform inform anyone to understand the level of authority and responsibility of the Officer or soldier, and in general the kind of job he does. It also identifies all soldiers as members of a single team. How to wear the uniform Rationale: The uniform you wear—as a soldier or as a living historian—represents a long tradition of courage, resoluteness, selflessness, and sacrifice. The manner in which you wear the uniform is not a trivial thing. But keep in mind that wearing it improperly cannot reflect on the soldiers who wore it under enemy fire. But it can reflect on you. The charge is on you to wear it in a way that would not suggest a lack of respect for those who wore it in earnest. Manner of wearing the uniform: The uniform should be kept clean and neat and in good repair to the extent possible. Reenactors get this backwards in their fevered desire to look like seasoned field soldiers. Here’s a philosopical view: A soldier is a man trying to stay clean and presentable under impossible conditions. -

Teresa Barger '73 Address Santa Catalina Alumnae Reunion March

Teresa Barger ’73 Address Santa Catalina Alumnae Reunion March 24, 2018 Thank you so much to the school and my class for this honor. 1969 was a weird year. The year we entered Catalina, the country was deeply divided by the Vietnam War; the nation was just getting over the assassination of Martin Luther King and the race riots that followed; and the Summer of Love with its ethic of “If it feels good, do it” was devolving into craziness. Only a month before school started, a Catalina alumna and cousin of our classmates Katie Budge and Marian Miller was killed by the Charles Manson “family.” But what did I know? I arrived anxiously at Catalina from Saudi Arabia wearing the coolest footwear I had—goatskin sandals with tire tread soles. These were the height of fashion in Saudi Arabia but not exactly huaraches or whatever the cool kids like Dana Hees would wear. And since it was so very cold here, I was never without my trusty navy blue raincoat with its fake sheepskin lining … in hideous red. Since I apparently greeted everyone I met with some exciting tidbit about the oppression of the Palestinian refugees, Joan Frawley later told me she thought I was a refugee. The first time I knew that we should care about the Vietnam War was when Mary Pickering wore a black armband at school on the day of the Moratorium to protest the Vietnam War. I had to look that one up—“moratorium.” Now I think back and wonder how those few nuns kept it together.