Secrets of the High Woods Research Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement to Agenda Agenda Supplement for Cabinet, 04/10

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Head of Finance and Governance Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Graham Thrussell on 01243 534653 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Cabinet will be held in Committee Room 1 at East Pallant House Chichester on Tuesday 4 October 2016 at 09:30 MEMBERS: Mr A Dignum (Chairman), Mrs E Lintill (Vice-Chairman), Mr R Barrow, Mr B Finch, Mrs P Hardwick, Mrs G Keegan and Mrs S Taylor SUPPLEMENT TO THE AGENDA 9 Review of Character Appraisal and Management Proposals for Selsey Conservations Area and Implementation of Associated Recommendations Including Designation of a New Conservation Area in East Selsey to be Named Old Selsey (pages 1 to 12) In section 14 of the report for this agenda item lists three background papers: (1) Former Executive Board Report on Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work - 8 September 2009 (in the public domain). (2) Representation form Selsey Town Council asking Chichester District Council to de-designate the Selsey conservation area (3) Selsey Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Proposals January 2007 (in the public domain). These papers are available to view as follows: (1) is attached herewith (2) has been published as part of the agenda papers for this meeting (3) is available on Chichester District Council’s website via this link: http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5298&p=0 http://www.chichester.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=5299&p=0 Agenda Item 9 Agenda Item no: 8 Chichester District Council Executive Board Tuesday 8th September 2009 Conservation Areas: Current Progress on Character Appraisals, Article 4 Directions and programme for future work 1. -

This Email Was Scanned by the Government Secure Intranet Anti-Virus Service Supplied by Vodafone in Partnership with Symantec

From: Catherine Myres To: Common Land Casework Subject: COM749 Date: 11 November 2015 18:55:44 Attachments: Final letter of mass objection including 140 names.doc 0490_001.pdf To whomever it may concern Please find attached a petition which was signed by those closest to these commons opposing the proposed fence. The letter was sent to Sussex Wildlife Trust. I note in their application they claim there is general agreement for their fencing, but this is not the case, as this letter and petition prove among those who live closest to the commons. SWT are aware of the high level of opposition but have chosen not to inform you of this. I don’t know if this invalidates their application but it is certainly unethical. Catherine Myres & Lucy Petrie Catherine Myres Old Rectory Cottage Trotton Nr Petersfield Hants GU31 5EN 01730 814170 07989 491383 This email was scanned by the Government Secure Intranet anti-virus service supplied by Vodafone in partnership with Symantec. (CCTM Certificate Number 2009/09/0052.) In case of problems, please call your organisations IT Helpdesk. Communications via the GSi may be automatically logged, monitored and/or recorded for legal purposes. 4th December 2013 Gemma Harding Sussex Wildlife Trust Woods Mill Henfield West Sussex BN5 9SD Dear Gemma Ref: Iping Common Proposal to permanently fence Iping & Trotton Commons As residents of these parishes and frequent users of Iping and Trotton Commons, we are writing to object to the proposed permanent perimeter fencing of these areas. We have collected over 140 signatures in opposition to the fencing. 95% live within the immediate vicinity of the common and are regular users. -

13742 the London Gazette, Ist November 1977 Home Office

13742 THE LONDON GAZETTE, IST NOVEMBER 1977 CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENTS Black Notley Parish Council and People. Bleasby, People of COM(77) 483 FINAL Bletchingley Women's Institute. R/2347/77. Commission communication to the Council on Blockley Parish Council. the energy situation in the Community and in the world. Borley, People of Boughton Aluph and Eastwell, People of COMMISSION DOCUMENT DEPOSITED SEPARATELY Boys' Brigade. R/2131/77. Letter of amendment to the preliminary draft Brackley, People of general budget of the European Communities for 1978. Bracknell Development Corporation. Bracknell District Council. COM(77) 467 FINAL Braintree District Council and People. R/2361/77. Report from the Commission to the Council on Braunstone, People of the application to exported products of Council Regula- Breadsall, People of tion (EEC) No. 2967/76 laying down common standards Brighton Corporation. for the water content of frozen and deep-frozen chickens, British Association of Accountants and Auditors. hens and cocks. British Bottlers Institute. British Constitution Defence.Committee (Liverpool). COM(77) 443 FINAL British Dental Association. R/2355/77. Commission communication to the Council on 'British Medical Association. improving co-ordination of national economic policies. British Optical Association. COM(77) 473 FINAL British Railways Board. Bromesberrow Parish Council. R/23 87/77. Report on the opening, allocation and manage- Bromley Corporation. ment of the Community tariff quota in 1977 for frozen Brook, Milford Sandhills, Witley and Wormley, People of beef and veal. Broxtowe District Council. COM(77) 494 FINAL Buckingham Town Council. R/2473/77. Annual Report on the economic situation in the Burnham-on-Sea and Highbridge Town Council. -

Chichester Natural History Society

Chichester Natural History Society Registered Charity No 259211 Chair: Christian Hance 389 Chichester Road, Bognor Regis, PO21 5BU (01243 825187) Membership: Heather Hart The Hays, Bridle Lane, Slindon Common, Arundel, BN18 0NA (01243 814497) Website: www.chichesternaturalhistorysociety.org.uk NEWSLETTER No 200 May 2021 FROM THE CHAIR Good Morning. As the country emerges from our “battle” with Covid 19, I am looking forward to enjoying this summer and really appreciating the wildlife in our local area. Whilst it will be great to have all restrictions removed, I hope that we do not lose the increased community spirit and politeness that developed during the lockdowns. Our first summer field outings have started and have proved very popular. Indeed, the limited space available on each walk, combined with the heavy demand from members, has meant that the field outing organiser’s husband has had to miss out! However, I am hopeful that I can attend the next outing, when numbers will not be limited. Alongside the summer field outings, we will also be carrying out our annual surveys of the ecological succession at Medmerry. I would like to take this opportunity to remind members that we have three pieces of equipment available for members to borrow. We have two types of Bat detector available, a static one and a handheld device. If you would like to book a slot to borrow either of these please contact Linda Smith. Following on from last year, I will be carrying out some bat surveys around the NT North Wood, using the handheld detector. If you would like to accompany me, please drop me a line. -

CDAS – Chairman's Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We Still Plan to Do the Geophysical Survey at Fishbourne Once

CDAS – Chairman’s Monthly Letter – March 2020 Fieldwork We still plan to do the geophysical survey at Fishbourne once the weather improves and the field starts to dry out. Coastal Monitoring Following the visit to Medmerry West in January we made a visit to Medmerry East. Recent storms had made a big change to the landscape. As on our last visit to the west side it was possible to walk across the breach at low tide. Some more of the Coastguard station has been exposed. However one corner has now disappeared. It was good that Hugh was able to create the 3D Model when he did. We found what looks like a large fish trap with two sets of posts running in a V shape, each arm being about 25 metres long. The woven hurdles were clearly visible. Peter Murphy took a sample of the timber in case there is an opportunity for radiocarbon dating. We plan to return to the site in March to draw and record the structure. When we have decided on a date for this work I will let Members know. Condition Assessment – Thorney Island The annual Condition Assessment of the WW2 sites on Thorney Island will be on Tuesday 10th March, meeting at 09:30 at the junction of Thorney Road and Thornham Lane (SU757049). If you would like to join us and want to bring a car onto the base you need to tell us in advance, so please email the make, model, colour and registration number of your car to [email protected] by Friday 6 March. -

Planning Committee Reports Pack And

Public Document Pack JOHN WARD East Pallant House Director of Corporate Services 1 East Pallant Chichester Contact: Sharon Hurr on 01243 534614 West Sussex Email: [email protected] PO19 1TY Tel: 01243 785166 www.chichester.gov.uk A meeting of Planning Committee will be held virtually on Wednesday 31 March 2021 at 9.30 am MEMBERS: Mrs C Purnell (Chairman), Rev J H Bowden (Vice-Chairman), Mr G Barrett, Mr R Briscoe, Mrs J Fowler, Mrs D Johnson, Mr G McAra, Mr S Oakley, Mr R Plowman, Mr H Potter, Mr D Rodgers, Mrs S Sharp and Mr P Wilding AGENDA 1 Chairman's Announcements Any apologies for absence which have been received will be noted at this stage. The Planning Committee will be informed at this point in the meeting of any planning applications which have been deferred or withdrawn and so will not be discussed and determined at this meeting. 2 Approval of Minutes (Pages 1 - 10) The minutes relate to the meeting of the Planning Committee held on 3 March 2021. 3 Urgent Items The chairman will announce any urgent items that due to special circumstances will be dealt with under agenda item 8 (b). 4 Declarations of Interests (Pages 11 - 12) Details of members’ personal interests arising from their membership of parish councils or West Sussex County Council or from their being Chichester District Council or West Sussex County Council appointees to outside organisations or members of outside bodies or from being employees of such organisations or bodies. Such interests are hereby disclosed by each member in respect of agenda items in the schedule of planning applications where the Council or outside body concerned has been consulted in respect of that particular item or application. -

Hydrological Modelling for the Rivers Lavant and Ems

Hydrological Modelling for the Rivers Lavant and Ems S.J. Cole, P.J. Howard and R.J. Moore Version 1.1 September 2009 Acknowledgements The following Environment Agency representatives are thanked for their involvement in the project: Paul Carter, John Hall, Colin Spiller, Tony Byrne, Mike Vaughan and Chris Manning. At CEH, Vicky Bell and Alice Robson are thanked for their contributions. Revision History Version Originator Comments Date 1.0 Cole, Draft of Final Report submitted to the 14 August 2009 Howard, Environment Agency for comment. Moore 1.1 Cole, Revision incorporating feedback 30 September 2009 Howard, from the Environment Agency. Moore Centre for Ecology and Hydrology Maclean Building Crowmarsh Gifford Wallingford Oxfordshire OX10 8BB UK Telephone +44 (0) 1491 838800 Main Fax +44 (0) 1491 6924241 ii Acknowledgements CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................... v List of Figures................................................................................................................ vii Executive Summary....................................................................................................... xi 1 Introduction......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview.............................................................................................................. -

Serving the Communities of Tillington, Duncton & Upwaltham

ISSUE 54 MAY 2021 FREE Serving the Communities of Tillington, Duncton & Upwaltham The Manor Black Magic Kids’ Micro Anti-social of Dean of Charcoal Pages Weddings Driving p.12 p.14 In the Middle p.28 p.31 TREVOR DUMMER CARPENTRY AND JOINERY PURPOSE MADE REPLACEMENT WINDOWS STAIRS DOORS AND FRAMES KITCHENS FITTED BOOKCASES BEDROOM UNITS DESIGNED AND FITTED SECURITY LOCKS NO JOB TOO SMALL FREE ESTIMATES TELEPHONE PULBOROUGH 01798 872169 ● Country Dining ● Real Ale ● Log Fires ● Quiet Garden ● Accommodation The Horse Guards Inn Tillington, West Sussex GU28 9AF 01798 342 332 www.thehorseguardsinn.co.uk K & J CATERING FOR ANY OCCASION 1 The Gardens, Fittleworth, Pulborough West Sussex RH20 1HT 01798 865982 Mobile 07989620857 email: [email protected] Kate Knight 1 P PHILLIPS CONTRACTORS LTD Agricultural & Industrial Building Contractors Dairy Buildings Industrial Units Slurry Schemes Water Mains Grain Stores Cladding and Sheet Roofing Livestock Buildings Plus all associated Groundworks We offer a complete service, from design to completion Telephone: 01798 343392 Email: [email protected] Web:www.ppcontractorsltd.co.uk 5th GENERATION, LOCAL FAMILY RUN INDEPENDENT FUNERAL DIRECTORS 24 Hours Service Private Chapel of Rest Monumental Stones supplied Pre-Paid Funeral Plans available Grave Maintenance Service The Gables, Tillington, GU28 9AB Tel: 01798 342174 Fax: 01798 342224 Email: [email protected] The perfect venue for your event, class, indoor or outdoor activity, wedding reception or other special occasion Set in its own extensive grounds with large car park and stunning views of the Downs, the hall’s excellent facilities include a fully equipped kitchen, main hall with seating for 80, separate meeting room with conference table and large AV screen. -

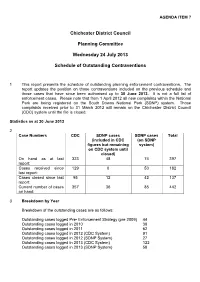

Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions

AGENDA ITEM 7 Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 24 July 2013 Schedule of Outstanding Contraventions 1 This report presents the schedule of outstanding planning enforcement contraventions. The report updates the position on those contraventions included on the previous schedule and those cases that have since been authorised up to 30 June 2013. It is not a full list of enforcement cases. Please note that from 1 April 2012 all new complaints within the National Park are being registered on the South Downs National Park (SDNP) system. Those complaints received prior to 31 March 2012 will remain on the Chichester District Council (CDC) system until the file is closed. Statistics as at 30 June 2013 2 Case Numbers CDC SDNP cases SDNP cases Total (included in CDC (on SDNP figures but remaining system) on CDC system until closed) On hand as at last 323 48 74 397 report: Cases received since 129 0 53 182 last report: Cases closed since last 95 12 42 137 report: Current number of cases 357 36 85 442 on hand: 3 Breakdown by Year Breakdown of the outstanding cases are as follows: Outstanding cases logged Pre- Enforcement Strategy (pre 2009) 44 Outstanding cases logged in 2010 38 Outstanding cases logged in 2011 62 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (CDC System) 91 Outstanding cases logged in 2012 (SDNP System) 27 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (CDC System) 122 Outstanding cases logged in 2013 (SDNP System) 58 4 Performance Indicators Financial Year 2013-2014 CDC Area Only a Acknowledge complaints within 5 days of receipt 92 -

The London Gazette, 17 April, 1925

2620 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 17 APRIL, 1925. Boad from the Angmering—Clapham road Gatehouse Lane from the Midhurst—Peters- near Avenals Farm to the Arundel—Worthing field road at Cumberspark Wood via Gatehouse road about 600 yards east of the Woodman's to the road junction at Terwick Common about Arms. 200 yards west of Dangstein Lodge. Boad from South Stoke to the bridge over Boad from the Midhurst—Petersfield road the Biver Arun at Off ham including the branch near Lovehill Farm via Dumpford House and to the Black Babbit towards Offham Hanger. Nye Wood House to the Bogate—Bogate Broadmark Lane, Bustington, from the road Station road near Sandhill House. junction about 400 yards east of the Church Torberry Lane from the South Harting— to .the sea. Petersfield road at Little Torberry Hill to the Greyhound Inn. Boad from the South Harting—Petersfield Rural District of Horsham. road at the county boundary at Westons via Boad from the Horsham—Cowfold road near Byefield Cottages to the road junction at Newells Pond via Prings Farm, Peartree Cor- Brickkiln; Copse near Bival Lodge. ner and Stonehouse Farm to its junction with Garbitts Lane, Bogate, from the Midhurst— the Belmoredean—Partridge Green road at Petersfield road to the Bogate—Bogate Station Danefold Corner. road. Boad from tha road junction near Park Farm Boad from the Midhurst—Petersfield road at about 1$ miles north of Horsham via Lang- Fyning to the road junction at Terwick Com- hurst and Friday Street to the Clark's Green— mon about 200 yards west of Dangstein Lodge. -

This Report Updates Planning Committee Members on Current Appeals and Other Matters

South Downs National Park Planning Committee Report of the Director Of Planning and Environment Services Schedule of Planning Appeals, Court and Policy Matters Date between 21/06/2019 and 19/07/2019 This report updates Planning Committee members on current appeals and other matters. It would be of assistance if specific questions on individual cases could be directed to officers in advance of the meeting. Note for public viewing via Chichester District Council web siteTo read each file in detail, including the full appeal decision when it is issued, click on the reference number (NB certain enforcement cases are not open for public inspection, but you will be able to see the key papers via the automatic link to the Planning Inspectorate). * - Committee level decision. 1. NEW APPEALS SDNP/18/06032/LIS Burton Mill, Burton Park Road, Barlavington, GU28 0JR - Duncton Parish Council Replacement of all existing windows with new double glazed units and revised frame design and reveal an obscured window. Case Officer: Beverley Stubbington Written Representation SDNP/18/06483/FUL East Marden Farm, Wildham Lane, East Marden, Marden Parish Council Chichester, West Sussex, PO18 9JE - Replacement of former agricultural buildings with 3 no. dwellings for tourism use. Case Officer: John Saunders Written Representation SDNP/18/05093/LDE Buryfield Cottage, Sheepwash, Elsted, Midhurst, West Elsted and Treyford Parish Sussex, GU29 0LA - Existing lawful development Council certificate for occupation of a dwellinghouse without complying with an agricultural occupancy condition. Case Officer: John Saunders Informal Hearing 2. DECIDED SDNP/18/01754/FUL Spindles East Harting Street East Harting Petersfield West Harting Parish Council Parish Sussex GU31 5LY - Replacement 1 no. -

HARTING PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting of the Planning

HARTING PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the meeting of the Planning Committee held at 7.10 pm in the Harting Congregational Church Hall, South Harting on Monday 5 August 2019 Present: Mrs Bramley (Chair), Mr Bonner, Mrs Curran, Mrs Dawson, Mrs Gaterell, Mrs Martin and Mr Shaxson. In attendance: Trish Walker, Parish Clerk 10. Apologies for absence: None 11. Declarations of Interest: All the councillors present declared a prejudicial interest in item 6.5 on the agenda. 12. Members of the Public Present: None 13. Minutes of the meeting on 11 July 2019: Having been agreed, the minutes were signed by the Chairman. 14. Matters of Urgent Public Importance: None. 15. Current Planning Applications: 15.1. SDNP/19/03175/TCA Notification of intention to fell 4 no. Douglas Fir trees. Ladymead East Harting Street East Harting Petersfield West Sussex GU31 5LZ No objection 15.2. SDNP/19/03007/HOUS Erection of orangery to the south elevation of property. Bridge Meadow Elsted Road South Harting GU31 5LS No objection. However, the Council would like to draw attention to policy SD8 (Dark Skies) as there is no apparent detail within the application to show how potential light spill from the orangery will be mitigated. 15.3. SDNP/19/03168/LIS Replacement of 6 no. windows and 1 no. door on west elevation. Replacement of 1 no. door on adjacent single storey. Rooks Cottage North Lane South Harting GU31 5PZ No objection. The Council supports the introduction of double glazing in this instance for the reasons that have been stated so clearly by the applicant.