Folk Song of the American Negro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CB-1990-03-31.Pdf

TICKERTAPE EXECUTIVES GEFFEN’S NOT GOOFIN’: After Dixon. weeks of and speculation, OX THE rumors I MOVE I THINK LOVE YOU: Former MCA Inc. agreed to buy Geffen Partridge Family bassist/actor Walt Disney Records has announced two new appoint- Records for MCA stock valued at Danny Bonaduce was arrested ments as part of the restructuring of the company. Mark Jaffe Announcement about $545 million. for allegedly buying crack in has been named vice president of Disney Records and will of the deal followed Geffen’s Daytona Beach, Florida. The actor develop new music programs to build on the recent platinum decision not to renew its distribu- feared losing his job as a DJ for success of The Little Mermaid soundtrack. Judy Cross has tion contract with Time Warner WEGX-FM in Philadelphia, and been promoted to vice president of Disney Audio Entertain- Inc. It appeared that the British felt suicidal. He told the Philadel- ment, a new label developed to increase the visibilty of media conglomerate Thom EMI phia Inquirer that he called his Disney’s story and specialty audio products. Charisma Records has announced the appointment of Jerre Hall to was going to purchase the company girlfriend and jokingly told her “I’m the position of vice president, sales, based out of the company’s for a reported $700 million cash, going to blow my brains out, but New York headquarters. Hall joins Charisma from Virgin but David Geffen did not want to this is my favorite shirt.” Bonaduce Records in Chicago, where he was the Midwest regional sales engage in the adverse tax conse- also confessed “I feel like a manager. -

There & Back Again: a Radio Story Voice Work for a Cup of Coffee

November 23, 2015, Issue 475 There & Back Again: A Radio Story In 1987, 25-year-old Tom Baldrica was managing a Minneapolis sporting goods store when a 19-year-old buddy called him home to help launch a newly inherited radio station. “It was like the ultimate class project,” Baldrica says. “We picked the call letters, slogan and just made shit up. We put it on the air as Country on April 8, 1988.” Twenty-seven years later Baldrica’s back at WUSZ/Hibbing, MN (launched as WCDK), not just in afternoons, but as Corporate Country Brand Strategist for Midwest (CAT 9/4). Country Aircheck wanted to know more about his full-circle return. For The Records: Baldrica spent 21 years on the label side, of course, leaving radio for records in 1993. “The station was a Gavin reporter, so I got to know the guys calling from Nashville Pull House: WKXC/Augusta, GA hosts its annual like Jack Purcell, George Briner and the late greats David Haley Kicks 99 Guitar Pull. Pictured (l-r) are Big Loud’s David Clapper, and Chuck Thagard,” he says. Intrigued by Baldrica’s passion for MCA’s Sam Hunt, Dot’s EJ Bernas and Maddie & Tae’s the music, Thagard recruited him as Southeast regional for BNA. Maddie Marlowe and Tae Dye, Black River’s Craig Morgan The label years were exciting, especially early on. “What we and Megan Boardman, Elektra/WAR’s Jana Kramer, the accomplished at BNA with [Kenny] Chesney and Lonestar, and just station’s Chris O’Kelley, Hill’s Jeri Cooper, UMG/Nashville’s the group of people who were there, that’s what I loved most,” he Royce Risser, Valory’s Thomas Rhett and Ashley Sidoti and says. -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, January 10, 2019 NEWS CHART ACTION Dierks Bentley Teases Winter Leg Of New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position Burning Man Tour ‘On Ice’ Some Of It/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 66 What Happens In A Small Town/Brantley Gilbert & Lindsay Ell/Valory — 67 Good As You/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 71 Kiss That Girl Goodbye/Aaron Watson/BIG Label Records — 76 One Less Girl/JD Shelburne/JD Shelburne Music LLC — 77 Get Away/Ryan Sims/High 4 Recordings/Hive Records — 79 Where I Come From/Ddendyl Hoyt/Arrow Music Agency — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase Beautiful Crazy/Luke Combs/Columbia Nashville/River House Artists — 520 What Makes You Country/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 349 Here Tonight/Brett Young/BMLG — 340 Some Of It/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 335 This Is It/Scotty McCreery/Triple Tigers Records — 332 What Happens In A Small Town/Brantley Gilbert & Lindsay Ell/Valory — 330 Good As You/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 309 Dierks Bentley will launch the winter leg of his 2019 Burning Man Tour next week in Canada. Ahead of the run, he and tourmates Jon Pardi and Most Added Tenille Townes had some fun and converged at the ice skating rink to prepare some “choreography” for the tour in a wonderful parody of sorts. song/artist/label—No. of Adds What Happens In A Small Town/Brantley Gilbert & Lindsay Ell/Valory — 28 Some Of It/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 27 On The Row: The Band Steele Good As You/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 22 Kiss That Girl Goodbye/Aaron Watson/BIG Label Records — 17 Beautiful Crazy/Luke Combs/Columbia Nashville/River House Artists — 15 Love Someone/Brett Eldredge/Atlantic Records/Warner Music Nashville — 12 Eyes On You/Chase Rice/Broken Bow — 11 Closer To You/Carly Pearce/Big Machine — 11 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, April 11, 2019 NEWS CHART ACTION New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position Lon Helton Receives Bob Kingsley Living No debut this week Legend Award Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 422 Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 362 Look What God Gave Her/Thomas Rhett/Valory — 221 Eyes On You/Chase Rice/Broken Bow — 169 GIRL/Maren Morris/Columbia Nashville — 152 Some Of It/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 136 Rearview Town/Jason Aldean/Broken Bow — 133 Every Little Honky Tonk Bar/George Strait/MCA Nashville — 122 Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 21 God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 15 Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 9 Bars & Churches/Aaron Goodvin/Reviver Records — 7 How Do You Know/Queeva/CMD Music — 7 All To Myself/Dan + Shay/Warner Bros./WAR — 6 Somebody's Gotta Be Country/Easton Corbin/Tape Room Records — 6 Lon Helton, one of Nashville’s most highly-regarded radio industry Freedom/Reba McEntire/Big Machine Records — 6 executives, was honored for his impact on country music with the Bob Kingsley Living Legend Award April 10 at the Grand Ole Opry House. On Deck—Soon To Be Charting The award was created in 2014 to recognize the most deserving song/artist/label—No. of Spins individuals in the music business. The evening beneftted the Opry Trust I Can Do Hard Things/Jennifer Nettles/Big Machine — 150 Fund, which for more than 50 years has supported members of the I Love The Lie/Kree Harrison/Visionary Records — 146 country music community in need. -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

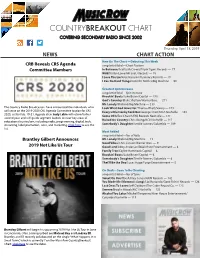

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, April 18, 2019 NEWS CHART ACTION New On The Chart —Debuting This Week CRB Reveals CRS Agenda song/artist/label—Chart Position Committee Members In Between/Scotty McCreery/Triple Tigers Records — 77 Wild/Katlyn Lowe/HK and J Records — 78 I Love The Lie/Kree Harrison/Visionary Records — 79 I Can Do Hard Things/Jennifer Nettles/Big Machine — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 290 God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 271 Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 210 The Country Radio Broadcasters have announced the individuals who Look What God Gave Her/Thomas Rhett/Valory — 173 will serve on the 2019-2020 CRS Agenda Committee to plan for CRS Every Little Honky Tonk Bar/George Strait/MCA Nashville — 143 2020, set for Feb. 19-21. Agenda chair Judy Lakin will return for her Some Of It/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 141 second year, and will guide segment leaders to steer key areas of Raised On Country/Chris Young/RCA Nashville — 117 educational curriculum, including radio, programming, digital, tech, streaming, label promotion, sales, and marketing. Click here to see the Somebody's Daughter/Tenille Townes/Columbia — 109 list. Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Brantley Gilbert Announces Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 11 Good Vibes/Chris Janson/Warner Bros. — 9 2019 Not Like Us Tour Good Lord/Abby Anderson/Black River Entertainment — 6 Family Tree/Caylee Hammack/Capitol — 6 Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 6 Somebody's Daughter/Tenille Townes/Columbia — 6 That'll Be the Day/Lucas Hoge/Forge Entertainment — 5 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, April 4, 2019 NEWS CHART ACTION EXCLUSIVE: Brooks & Dunn Discuss New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position Collaborating With A New Generation Of God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 33 Talent On Reboot Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 46 Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 75 Bars & Churches/Aaron Goodvin/Reviver Records — 77 Somebody's Gotta To Be Country/Easton Corbin/Tape Room Records — 79 Freedom/Reba McEntire/Big Machine Records — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 721 Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 528 Look What God Gave Her/Thomas Rhett/Valory — 313 Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 195 Good As You/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 186 Every Little Honky Tonk Bar/George Strait/MCA Nashville — 166 What Happens In A Small Town/Brantley Gilbert & Lindsay Ell/Valory — 139 Rearview Town/Jason Aldean/Broken Bow — 125 Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Click the photo to read the exclusive interview. God's Country/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 45 Knockin' Boots/Luke Bryan/Capitol — 42 Opry Entertainment Launches Video Series Mr. Lonely/Midland/Big Machine — 17 “The Write Stuff” Bars & Churches/Aaron Goodvin/Reviver Records — 13 Wild/Katlyn Lowe/HK and J Records — 6 Freedom/Reba McEntire/Big Machine Records — 5 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. of Spins I Love The Lie/Kree Harrison/Visionary Records — 135 I Can Do Hard Things/Jennifer Nettles/Big Machine — 133 Wild/Katlyn Lowe/HK and J Records — 121 Sweet On You/The Ashley Sisters/GKM Records — 105 Say Goodbye/Charles Parker/Charles Parker Music — 101 Opry Entertainment Group is set to launch their newest video series “The Write Stuff,” offering insight into the biggest hits for country’s top stars, as well as exclusive Opry performances. -

Cheap Speech and What It Will Do

Cheap Speech and What It Will Do Eugene Volokht CONTENTS CHEAP SPEECH ........................................... 1808 A. Music and the Electronic Music Databases .................... 1808 1. The New System .................................... 1808 a. What It Will Look Like ............................. 1808 b. Why It Will Look Like This .......................... 1810 2. How the New System Will Change What Is Available .......... 1814 3. Dealing with Information Overload ...................... 1815 4. Will Production Companies Go Along? .................... 1818 B. Books, Magazines, and Newspapers ......................... 1819 1. Introduction . ...................................... 1819 2. Short Opinion Articles and Home Printers ................. 1820 3. Cbooks and Books, Magazines, and Newspapers ............. 1823 4. How the New Media Will Change What Is Available .......... 1826 a. More Diversity . ................................. 1826 b. Custom-Tailored Magazines and Newspapers ............ 1828 5. Dealing with Information Overload ...................... 1829 C. Video (TV and Movies) ................................... 1831 II. SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES ..................................... 1833 A. Democratization and Diversification ......................... 1833 B. Shift of Control from the Intermediaries and What It Will Mean ...... 1834 1. Shift of Control to Listeners ........................... 1834 2. Shift of Control to Speakers: The Decline of Private Speech Regulations ......................................... 1836 C. Poor -

The Complete Ask Scott

ASK SCOTT Downloaded from the Loud Family / Music: What Happened? website and re-ordered into July-Dec 1997 (Year 1: the start of Ask Scott) July 21, 1997 Scott, what's your favorite pizza? Jeffrey Norman Scott: My favorite pizza place ever was Symposium Greek pizza in Davis, CA, though I'm relatively happy at any Round Table. As for my favorite topping, just yesterday I was rereading "Ash Wednesday" by T.S. Eliot (who can guess the topping?): Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree In the cool of the day, having fed to satiety On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained In the hollow round of my skull. And God said Shall these bones live? shall these Bones live? And that which had been contained In the bones (which were already dry) said chirping: Because of the goodness of this Lady And because of her loveliness, and because She honours the Virgin in meditation, We shine with brightness. And I who am here dissembled Proffer my deeds to oblivion, and my love To the posterity of the desert and the fruit of the gourd. It is this which recovers My guts the strings of my eyes and the indigestible portions Which the leopards reject. A: pepperoni. honest pizza, --Scott August 14, 1997 Scott, what's your astrological sign? Erin Amar Scott: Erin, wow! How are you? Aries. Do you think you are much like the publicized characteristics of that sun sign? Some people, it's important to know their signs; not me. -

Highway's Song

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news April 2010 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 9, No. 7 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 Mission Contributors Souls on Fire Concert Full Circle.. …………4 Arlo Guthrie & Family Recordially, Lou Curtiss Alex Chilton Front Porch... ………6 G String Chronicles, Part 2 Hutchins Consort Postcard from Nashville Parlor Showcase …10 Shawn Rohlf Ramblin’... …………12 Bluegrass Corner The Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Stages Highway’s Song. …14 Texas Tornados Leon Redbone Of Note. ……………16 Jon Swift Ringo Jones Gregory Page Coco & Lafe Tim Easton Mike Quick Valhalla Hill ‘Round About ....... …18 April Music Calendar The Local Seen ……19 Photo Page APRIL 2010 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat Music to Set Your RSAN ODUIEGBO ADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news this demanding vocal style will be Soul on Fire! demonstrated by singer-composer Jesus Montoya. Gypsy by birth, Montoya was MISSION CONTRIBUTORS born and raised in Seville, Spain, but now makes his home in Long Beach. To promote, encourage, and provide an by Paul Hormick Ahmadand’s rock band Junoon for the FOUNDERS He is the artistic director of the well- alternative voice for the great local music that Ellen and Lyle Duplessie Summit for Sustainable Development. is generally overlooked by the mass media; After the disintegration of the renowned Montoya Flamenco Dance Liz Abbott efore the conquistadores set sail namely the genres of alternative country, Kent Johnson Roman Empire, the Moors – Arabs and Music Company. Americana, roots, folk, blues, gospel, jazz, and for the New World, before First played by the Gypsies of PUBLISHERS from North Africa – ruled Spain for bluegrass. -

How Music Companies Discover, Develop

How music companies discover, develop & promote talent Front Cover: Photographer credits Little Boots Daniel Sannwald Mark Ronson David Hughes Deadmau5 Spiros Politis Coldplay Kevin Tachman Jamie Cullum Deborah Anderson contents 4 Introduction 5 Executive Summary 6 Section 1: The Circle of Investment 10 Section 2: Discovering and Nurturing Talent 16 Section 3: Putting the Release Together 20 Section 4: Marketing and Promotion 27 A Broad Range of Artists 30 Recorded and Live Music Left: Deutsche Grammophon artist Anna Netrebko’s classical music is being brought to new audiences. Esther Haase/DG introduction BY JoHn KennedY & Alison WenHAm We have been fortunate to have had long by the challenges of running a business, which careers in the music industry. Over different requires totally different skills. Artists generally career paths, we have worked with great prefer to leave the complex administration artists and great record labels, and witnessed of a rights based business to someone else. first hand the unique combination of talent and teamwork that best reflects the A few years into the digital revolution, it has music business. now become clear that the internet is by itself no guaranteed route to commercial success. Today, we head organisations that together MySpace has more than 2.5 registered million represent virtually all the record companies hip hop acts, 1.8 million rock acts, 720,000 in the world. These range from the largest pop acts, and 470,000 punk acts. The gulf international major, with a roster of thousands between acclaim and anonymity, where of acts, to the smallest indie with a roster of record labels do their essential work, one or two. -

Where the Things

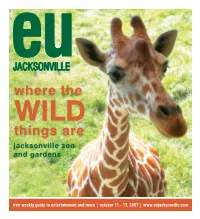

JACKSONVILLE where the WILD things are jacksonville zoo and gardens free weekly guide to entertainment and more | october 11 - 17, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 october 11-17, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents feature Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens ....................................................................................... PAGES 18-24 Zoo of Today & Tomorrow ..................................................................................... PAGES 18-19 Zoo Food & Events ................................................................................................ PAGES 19-20 Zookeeper Tours ................................................................................................... PAGES 21-22 Wild Things - The Young Adults of the Zoo ....................................................................PAGE 22 Zoo Education...............................................................................................................PAGE 23 Corny Maize ..........................................................................................................................PAGE 24 movies Movies in Theaters this Week .......................................................................................... PAGES 6-11 Michael Clayton (movie review) ...............................................................................................PAGE 6 Feel the Noise (movie review) ..................................................................................................PAGE 7 We Own the Night (movie -

Steve Ripley a Rock and Roll Legend in Our Own Backyard Who Has Worked with Some of the Greats

Steve Ripley A rock and roll legend in our own backyard who has worked with some of the greats. Chapter 01 – 1:16 Introduction Announcer: Steve Ripley grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from Glencoe High School and Oklahoma State University. He went on to become a recording artist, record producer, song writer, studio engineer, guitarist, and inventor. Steve worked with Bob Dylan playing guitar on The Shot of Love album and on The Shot of Love tour. Dylan listed Ripley as one of the good guitarist he had played with. Red Dirt was first used by Steve Ripley’s band Moses when the group chose the label name Red Dirt Records. Steve founded Ripley Guitars in Burbank, California, creating guitars for musicians like Jimmy Buffet, J. J. Cale, and Eddie Van Halen. In 1987, Steve moved to Tulsa to buy Leon Russell’s recording facility, The Church Studio. Steve formed the country band The Tractors and was the cowriter of the country hit “Baby Like to Rock It.” Under his own record label Boy Rocking Records, Steve produced such artists as The Tractors, Leon Russell, and the Red Dirt Rangers. Steve Ripley was sixty-nine when he died January 3, 2019. But you can listen to Steve talk about his family story, his introduction to music, his relationship with Bob Dylan, dining with the Beatles, and his friendship with Leon Russell. The last five chapters he wanted you to hear only after his death. Listen now, on VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 3:47 Land Run with Fred John Erling: Today’s date is December 12, 2017.