Left Behind: Troubled Foreclosed Properties and Servicer Accountability in Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law School Record, Vol. 43, No. 1 (Summer 1997) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Summer 6-1-1997 Law School Record, vol. 43, no. 1 (Summer 1997) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 43, no. 1 (Summer 1997)" (1997). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 81. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HE FUND �beL SCHO Scholarship Support The Mandel Legal Aid Clinic Student]ournals Moot Court Competition Student Activities and Programs Mentoring Programs And many more .... These needs and others are supported by annual gifts to the Fund for the Law School. Please use the enclosed envelope to make your THE LAW SCHOOL contribution. Your gift means more this year than ever as the Law THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO School strives to provide new opportunities for today's students. CONTENTS Summer 1997 F E A T u R E s One Final Note By Holly Davis '76 2 Editor Dan McGeehan E-Mail: [email protected] The Art of law and Economics Assistant Dean for Alumni Relations Holly C. Davis '76 By William Landes 4 E-Mail: [email protected] Credits Photography: Ariana Almajan '99: 18 (top). -

Honoring Who've Made a Difference

honoring Who’ve Made a 4Difference Business and Professional People for the Public Interest 4o Who’ve Made a Difference Awards Business and Professional People for the Public Interest 4oth Anniversary Celebration The Fairmont Chicago May 1, 2oo9 INTRODUCTION As our 40th Anniversary approached, BPI’s Board of It is BPI’s privilege to introduce our 40 Who’ve Made Directors decided to focus our celebration on the a Difference—a stunning kaleidoscope of vision and amazing range and richness of public interest work in accomplishment by a diverse group of individuals our region by shining a spotlight on people whose representing many different fields of endeavor— civil leadership, vision and courage have made a significant rights, education, law, housing, the arts, healthcare. difference in the lives of others—people whose efforts We honor their individual commitment and achievement derive from and contribute to the social justice values as we are inspired by their collective contribution to to which BPI has been dedicated for four decades. the people of the Chicago region. BPI issued an open Call for Nominations and convened How to estimate the impact of their efforts? As you read a Selection Committee of respected leaders from various through these brief narratives, you might consider what fields. The Committee faced a difficult challenge in life here would be like without their work. There would fulfilling its mandate of choosing “40 Who’ve Made a be significantly less equality of opportunity in housing, Difference” from scores of exceptional nominees. education and healthcare…less cultural vitality and After hours of research, review and deliberation, the opportunity to experience it…less access to justice.. -

To Lead and Inspire Philanthropic Efforts That Measurably Improve the Quality of Life and the Prosperity of Our Region

2008 ANNUAL REPORT To lead and inspire philanthropic efforts that measurably improve the quality of life and the prosperity of our region. OUR VALUES Five values define our promise to the individuals and communities we serve: INTEGRITY Our responsibility, first and foremost, is to uphold the public trust placed in us and to ensure that we emulate the highest ethical standards, honor our commitments, remain objective and transparent and respect all of our stakeholders. STEWARDSHIP & SERVICE We endeavor to provide the highest level of service and due diligence to our donors and grant recipients and to safeguard donor intent in perpetuity. DIVERSITY & INCLUSION Our strength is found in our differences and we strive to integrate diversity in all that we do. COLLABORATION We value the transformative power of partnerships based on mutual interests, trust and respect and we work in concert with those who are similarly dedicated to improving our community. INNOVATION We seek and stimulate new approaches to address what matters most to the people and we serve, as well as support, others who do likewise in our shared commitment to improve metropolitan Chicago. OUR VISION The Chicago Community Trust is committed to: • Maximizing our community and donor impact through strategic grant making and bold leadership; • Accelerating our asset growth by attracting new donors and creating a closer relationship with existing donors; • Delivering operational excellence to our donors, grant recipients and staff members. In 2008, The Chicago Community Trust addressed the foreclosure crisis by spearheading an action plan with over 100 experts from 70 nonprofit, private and public organizations. -

October 9, 2009 the City of Chicago's ARRA Collaboration with the Chicago Philanthropic Community

!# ! '"&%%' $ 1 October 9, 2009 Thank you for your interest in the Chicago Recovery Partnership six-month report. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 was passed during one of the most difficult economic times in a generation in order to provide urgently needed new revenue to cities and organizations across the nation. The City of Chicago responded to this important opportunity in an innovative way by partnering closely with Chicago’s supportive philanthropic community. The Recovery Act offers unique challenges for cities because these funds must be dispersed more quickly and tracked more closely than other federal grants. The Chicago Recovery Partnership was created to bring together City departments, local foundations and the business community to address these challenges, increase transparency, enhance Chicago’s ability to successfully compete for new federal funding opportunities, and consider how to sustain these benefits after federal funding is exhausted. This six-month report outlines the Recovery Partnership’s achievements to date, lessons learned and a plan to measure the impact of ARRA in Chicago through an academic evaluation collaborative. We believe the Recovery Partnership has the potential to become a national model for bringing together local governments, philanthropic and business organizations in order to maximize the impact of federal funding in cities. The Recovery Partnership is yet another example of how Chicago’s engaged civic community, working together with the City, helps to make the city a great place to live, work and raise a family. We are grateful to the numerous Recovery Partnership participants who have offered their time and expertise to help ensure the growth and success of our city for a new generation of residents. -

Philanthropy, Public Policy and Community Change SOWK 714 001 (3.0 Credit Hours)

LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK Philanthropy, Public Policy and Community Change SOWK 714 001 (3.0 Credit Hours) Prerequisites Prior coursework in or working knowledge of nonprofit management, public policy, philanthropy or fundraising is preferred. Course Description Organized philanthropy has developed from a long history of charitable giving to address social needs and causes, particularly in the United States. From the early pioneers – Carnegie, Rockefeller, Sage – to the philanthrocapitalists of the 21st century – Bill & Melinda Gates, Warren Buffet, Bono – giving from individuals, foundations and corporations is increasingly vital to the sustainability of organizations. In 2010, total charitable giving in the United States was approximately $291 billion, which is 3.8% more than in 2009. Giving by more than 76,500 U.S. grantmaking foundations in 2010 was between $41 and $46 billion – less than two years earlier in 2008, but an increase over 2009. Most foundations assumed an upward trajectory would continue for their assets, and thus their grantmaking dollars, but the seismic shift in the economy in 2008-09 rocked the philanthropy world and everyone has been affected. Average declines in foundation assets approached a record 22% by end of 2008 resulting in foundations reducing their giving by 8.4%, close to $4 billion, in 2009. The slow recovery experienced in 2010-11 continues to influence foundations, corporations and individuals to remain relatively flat during a time when the need for services has surged due to rising unemployment, the foreclosure crisis, a strained safety net, and a political environment that has slashed and stalled government funds. This course will examine the role philanthropy plays in supporting social and community change efforts designed to inform, reform and/or enhance public policy. -

Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best®

Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best® Benchmarks to Assess and Enhance Grantmaker Impact Copyright © 2009 National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Publishers, 2001 S Street NW, Suite 620, Washington, D.C. 20009. All rights reserved. The chapters and discussion questions in this publication (except portions of which reprint permission must be obtained from the primary sources) may be freely reproduced for educa- tional activities only. There is no requirement to obtain special permission for such uses. We do, however, ask that the follow- ing statement appear on all reproductions: Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best: Benchmarks to Assess and Enhance Grantmaker Impact by Niki Jagpal. Copyright © 2009 by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Washington, D.C. This permission statement only applies to the reproduction of materials for educational purposes only. Systematic or large- scale reproduction or distribution (more than 25 copies per year) or inclusion of any item from this publication in other publications for sale may be done only with prior written per- mission from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Communications Department, National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, 2001 S Street NW, Suite 620, Washington, D.C. 20009, fax: (202) 332-5084, email: [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-615-27727-1 Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best® Benchmarks to Assess and Enhance Grantmaker Impact Acknowledgements Over the past year, numerous people contributed Special thanks to the following for their to the development of this report. additional substantive assistance: Lori Bartczak, Rick Cohen, Kathleen Enright, Project Co-Directors: Aaron Dorfman Andrew Grant-Thomas, Robert Grimm, David and Niki Jagpal Harder, Nathan Henderson-James, Mark Kramer, Primary Author: Niki Jagpal Steven Lawrence, J. -

Communities and Criminal Justice: a Powerful Alignment

August 1996 Communities: Mobilizing Against Crime Making Partnerships Work The Latest Criminal Justice Videotape Series From NIJ: Research in Progress Learn about the latest developments in criminal justice research from prominent criminal justice experts. Each 60-minute VHS tape presents a well-known scholar discussing his or her current studies and how they relate to existing criminal justice research and includes the lecturer’s responses to audience questions. Law Enforcement Sentencing Policy NCJ 159739 NCJ 159740 Joel H. Garner, Ph.D., Use of Force By and Against Kim English, Ph.D. Managing Adult Sex Offenders in Police. Community Settings: A Containment Approach. NCJ 153273 NCJ 152236 Wesley Skogan, Ph.D. Community Policing in Peter W. Greenwood, Ph.D. Three Strikes, You’re Out: Chicago: Fact or Fiction? Benefits and Costs of California’s New Mandatory Sentencing Law. NCJ 153730 Lawrence W. Sherman, Ph.D. Reducing Gun Violence: NCJ 152237 Community Policing Against Gun Crime. Christian Pfeiffer, Ph.D. Sentencing Policy and Crime Rates in Reunified Germany. Drug AbuseTreatment NCJ 152692 Violence Prevention James Inciardi, Ph.D. A Corrections-Based Continuum NCJ 152235 of Effective Drug Abuse Treatment. Alfred Blumstein, Ph.D. Youth Violence, Guns, and Illicit Drug Markets. High-Risk Youth/ NCJ 152238 Arthur L. Kellermann, M.D., M.P.H. Understanding Child Abuse and Preventing Violence: A Public Health Perspective. NCJ 153270 NCJ 153850 Adele Harrell, Ph.D. Intervening With High-Risk Scott H. Decker, Ph.D., and Susan Pennell. Monitoring Youth: Preliminary Findings From the Children At- the Illegal Firearms Market. Risk Program. NCJ 153271 NCJ 153272 Marvin Wolfgang, Ph.D. -

Mundelein Reborn

THE MAGAZINE OF LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO WINTER 2012 Mundelein reborn PLUS PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2012 n HOMECOMING WELcome FROM THE PRESIDENT And CEO MICHAEL J. GARANZINI, S.J. Our world is a changing one. As we look at the world that our present students will inherit, we know that they will live in communities and participate in workplaces that are increasingly a mix of cultures, races, creeds, and values. We can see that technology will offer more and more information, and perhaps less and less analysis. We can envision a furthering of environmental degradation and depletion of the planet’s resources. And we anticipate that growing financial and educational gaps between and among different constituents in our societies will lead to even more political and social strife and upheaval around our worlds. Fundamentally, all education is about preparing students for their own future. It is about helping them become critical thinkers who can absorb and create new knowledge. It is about giving them the skills to lead and serve in the world they’re going to inhabit—in a world that will need their leadership. When Jesuits started educating children 450 years ago in Messina, Sicily, it was at the request president’S of the town’s merchant class. They wanted their report 2012 sons to take over the management not only of BEGINS AFTER PAGE 39 their companies but of their city. So the Jesuits devised an educational program, which has been reformed and fine-tuned since that time, Father Garanzini spoke to the City Club of Chicago, a group of to prepare people to be not just merchants, local community and business leaders, this fall. -

Citizens Changing Their Schools: a Midterm Report of the Annenberg Challenge

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 447 586 EA 030 745 AUTHOR Cushman, Kathleen; Cervone, Barbara TITLE Citizens Changing Their Schools: A Midterm Report of the Annenberg Challenge. INSTITUTION Brown Univ., Providence, RI. Annenberg Inst. for School Reform. PUB DATE 1999-04-00 NOTE 44p. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; *Academic Standards; Accountability; Cooperation; *Educational Change; Elementary Secondary Education; *Financial Support; *Participative Decision Making; Public Schools; School Community Relationship; *Teacher Improvement IDENTIFIERS *Annenberg Foundation ABSTRACT This report marks a midpoint in the Annenberg $500 million challenge to improve public schools. It comes at a time when evidence from the Annenberg Challenge's first projects has started to accumulate--and to suggest that the program is indeed having a beneficial impact on students, schools, and communities. This report also furnishes early lessons that have much to tell about effective school reform. In preparing this report, the Challenge's national office drew upon the findings of the independent research teams that evaluate each project. As an interim report, this one captures work in progress. The Annenberg Foundation sequenced its grant awards so that the work of the first could inform those that followed. Even the six oldest Challenge projects featured in this report (New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, the San Francisco Bay Area, and a national consortium of rural sites), therefore, stand at different stages of development, as do the local evaluations that chart their progress. Appendices provide additional information concerning principal investigators of Annenberg Challenge Research Teams, Challenge Site Evaluation Reports, and additional data concerning grants.(DFR) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

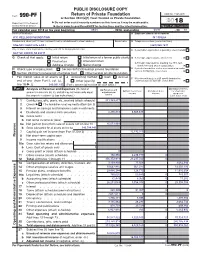

2018 W.K. Kellogg Foundation 990-PF

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2018 Department of the Treasury a Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service a Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2018 or tax year beginning 09/01 , 2018, and ending 08/31 , 20 19 Name of foundation A Employer identification number W.K. KELLOGG FOUNDATION 38-1359264 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) ONE MICHIGAN AVE EAST (269) 968-1611 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here a BATTLE CREEK, MI 49017 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here . a Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ..a H Check type of organization: ✔ Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ....a Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. -

Vanishing Act Thousands Are Being Deported Without a Chance to Appear Before an Immigration Judge

VOLUME 42 NUMBER 3 MAY/JUNE 2013 $5 Vanishing act Thousands are being deported without a chance to appear before an immigration judge. page 8 CHICAGOREPORTER.COM INSIDE May/June Founded in 1972, the Reporter is an investigative bimonthly that identifies, analyzes and reports on the social, eco- nomic and political issues of metropolitan Chicago with a focus on race and poverty. It is supported by grants from The Chicago Community Trust; Chicago Tribune Foundation; Richard H. Driehaus Foundation; Ford Foundation; Lloyd A. Fry Foundation; The Fund for Investigative Journalism; IRE Data Journalism Fund, sponsored by Google Ideas; McCormick Foundation; Open Society Foundations; Woods Fund of Chicago; and by subscriptions and individual contributions. FOUNDER John A. McDermott INTERIM PUBLISHER Laura S. Washington INTERIM EDITOR In recent months, several rallies in support of immigration reform have sprung up across the Rui Kaneya country. Yet, any reform measure that emerges may not benefit thousands of immigrants who have been deported without a judicial hearing. Photo by Lucio Villa. PRESENTATION EDITOR Christine Wachter REPORTERS Angela Caputo On the cover María Inés Zamudio Save the date 8 Speedy removals On Thursday, June 20, The WEB EDITOR Cassandra West The government is bypassing judicial Chicago Reporter will host a hearings in an attempt to swiftly deport reception at DreamBox Foto BLOGGER/REPORTER thousands of immigrants each year. Studio, 2415 W. North Ave., in Yana Kunichoff Humboldt Park, to showcase COPY EDITOR Also inside the work of photojournalism James Tehrani fellows Jonathan Gibby and 15 Ready to pull the trigger Lucio Villa. Make sure to PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWS Will mandatory prison time for gun subscribe to our weekly e-blast Jonathan Gibby possession make Chicago safer? at www.chicagoreporter.com Lucio Villa to ensure that you’re up to INTERNS 16 Her daughter, her legacy date on all the ways we’re Natasha Hemley Hadiya Pendleton’s mother was thrust into celebrating our 40th year. -

Scorecard 2011 July 1, 2010 - June 30, 2011

SMART WORK. GREAT CITY. Scorecard 2011 July 1, 2010 - June 30, 2011 Civic Consulting Alliance is a partnership that reshapes how the city works. 143 PROJECTS 670 PEOPLE We build pro bono teams of business experts, government leaders, and 19 our own staff. Together, we figure out workable and enduring ways to EDUCATION make our city more livable, affordable, and globally competitive. Provide all residents access to a world-class education Our clients include Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle, and other government executives 23 committed to leading tremendous reforms. ENVIRONMENT Make Chicago the greenest We stage a series of projects to create a sequence of results that, over city in the nation time, addresses complex issues and opportunities. 6 385 PARTNERS WORKFORCE Make Chicago’s workforce the Together, our partners and clients achieve a greater impact most globally competitive in than any organization could on its own: the world 11 City and County Mayor Emanuel Cook County PUBLIC SAFETY join forces for better, publishes transition saves $200 million Make Chicago the safest big streamlined services plan for residents city in the country and help its residents feel safe and secure $140 million relief for 15 pro bono partners 24 pro bono partners taxpayers could result from helped Mayor Emanuel helped President Preckwinkle 19 collaborative efforts, publish a transition plan publish a transition plan, 15 which Civic Consulting and and are supporting close a budget gap, and TRANSPORTATION partners identified and are many of the plan’s most launch a performance Create a first-rate helping to implement.