Reality, Tv, Celebrity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

Crowdgather (CRWG)

CORPORATE PRESENTATION April 2012 @CROWDGATHER 1 Safe Harbor This presentation contains forward-looking statements (as defined in Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended) concerning future events and the Company's growth and business strategy. Words such as "expects," "intends," "plans," "believes," "anticipates," "hopes," "estimates," and variations of such words and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Although the Company believes that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, no assurance can be given that such expectations will prove to have been correct. These statements involve known and unknown risks and are based upon a number of assumptions and estimates that are inherently subject to significant uncertainties and contingencies, many of which are beyond the control of the Company. Actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Factors that could cause actual results to differ materially include, but are not limited to changes in the Company’s business; competitive factors in the market in which the Company operates; risks associated with operations outside the United States; and other factors listed from time to time in the Company's filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The Company expressly disclaims any obligations or undertaking to release publicly any updates or revisions to any forward-looking statements contained herein to reflect any change in the Company's expectations with respect thereto or any change in events, conditions or circumstances on which any statement is based. -

UK Here They Come

Tuesday, December 6, 2005 Volume 132, Issue 14 Varsity players juggle rigorous academic and athletic schedules The University of Delaware's Independent Student Newspaper Since 1882 Sports Page 29 UK here they come ... Two students win prestigious award BY MARIAH-RUSSELL "I could go back to Kansas and my job in Staff Reporter retail clothing, or go to Egypt and study Arabic," In their spare time, they run · the Dead Sea he said. Marathon in Jordan and practice Brazilian Jiu- He chose the latter. Jitsu. On campus, they can be found giving tours Isherwood said he enjoyed his time in Egypt and researching in laboratories. so much that he spent 13 months of the past four But next year, they will both begin graduate years abroad, voyaging to Egypt, South Africa studies in England. And the British government and Morocco. In his travels, he researched will be picking up the tab - worth approximate African refugee camps, learned Arabic, worked ly $100,000. at a legal aid organization and taught English to Seniors Tom Isherwood and Jim Parris were refugees. named Marshall Scholars, making the university The following summer Isherwood went to one of only six schools to have more than one Morocco, where he lived with a host family and recipient Others include Georgetown, Stanford improved his Arabic. Then, last January, he and Yale Univeristies. began a seven-month stay in Egypt The Marshall Scholarship was founded by That spring, he worked as a research assis the British Parliament as part of the European tant for Dr. Barbara Harrell-Bond, a founder of Recovery Program in 1953. -

Celebrity News: Kristin Cavallari Reveals Her Third Wedding Anniversary Celebration with Jay Cutler

Celebrity News: Kristin Cavallari Reveals Her Third Wedding Anniversary Celebration With Jay Cutler By Cortney Moore Time sure does fly by! It’s only been three years since former Laguna Beach and The Hills reality TV star, Kristin Cavallari, tied the knot with Chicago Bears quarterback Jay Cutler in a celebrity wedding! In a celebrity interview with The Knot, Cavallari opened up about her third wedding anniversary with the NFL player. “We went to dinner at one of our favorite spots in Chicago called Blackbird, we had a four-course meal and a bottle of wine. I was a happy girl,” Cavallari said. Evidence of the joyous occasion was shown on Instagram, where Cavallari posted a photo of herself blowing a kiss at Cutler, captioned, “Happy anniversary to my man!” This happy celebrity news has us realizing that reality TV star Kristin Cavallari and Chicago Bears quarterback Jay Cutler know how to make a long-lasting relationship work. Cupid discusses below. A Broken Engagement Prior to the 2013 wedding between Cavallari and Cutler, the celebrity couple faced their own set of challenges. The couple got engaged in April 2011, but broke it off three months later. However, their split didn’t last long seeing as they were back together in December of that year. Cavallari detailed the reasons for their split in her book Balancing in Heels, stating, “I always go after what I want in life, with men or otherwise, and I never settle,” she went on to add, “If something doesn’t feel right, I act on it. -

2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Archives and Special Collections Newspaper 3-28-2006 2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006" (2006). Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper. 205. https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander/205 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 88, Issu e 22 March 28, 2006 Regis University --- - ----------- e a weekly publication ~1 an er The Jesuit University of the Rockies www.RegisHighlander.com Denver, Colorado Mathematics majors Nobel Laureate Lech Walesa speaks develop pattern in the Field House recognition system Chris Dieterich Erica Easter Editor-in-Chief Staff Reporter "Radishes." That's what former This past summer, senior mathemat President of Poland Lech Walesa ics major, Michael Uhrig, and junior called members of Poland's mathematics and chemistry double Communist Party last Friday evening major, Anthony Giordano, spent their as Regis hosted the former Polish days calculating. But, unlike the president and Nobel Peace Prize everyday calculations involved in fig Laureate in the Field House. "They uring out a tip or balancing a check were red on the outside, but white on book, Uhrig and Giordiano spent the inside." countless hours in a lab, programming One needs a sense of humor, it what would become a working "pattern would seem, to stare down the Soviet recognition" system. -

Scarlett Johansson

Cover_July 6/12/06 1:47 PM Page 1 3/C B G R july 2006 | volume 7 | number 7 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 PLUS REESE WITHERSPOON, JIM CARREY AND OTHER STARS GET ALL PHILOSOPHICAL Advertisement Hit TV Lovers Tune to TVtropolis Canada’s New Destination for TV Lovers Perhaps it first hit when you discovered your TVtropolis has all your favourites, series best friend has a name that rhymes with too young to be “classic” on a schedule that’s a female body part. Or the time you almost too good to be true. (Lucky for you, it planned your parents’ anniversary is true!) Weekdays in TVtropolis you’ll hoping it’d be as romantic as Brenda find TV greats, back-to-back: Seinfeld, Ellen, and Dylan’s graduation. Or that day at Grace Under Fire, Married… With Children, the dog park when you spotted the NewsRadio, Ned and Stacey, Frasier, Jack Russell terrier and fought the Beverly Hills 90210 and The Nanny. urge to have a staredown contest. Want a few more familiar faces? It might as well be spelled out in block letters Weekends in TVtropolis you on a 70-inch plasma screen: you, my friend, are a can explore your favourite TV fan of hit TV! From Seinfeld to Beverly Hills stars in a fresh new light with our 90210 to Frasier, you know and love ‘em all. -

Newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

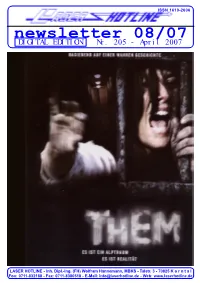

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 205 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 08/07 (Nr. 205) April 2007 editorial Gefühlvoll, aber nie kitschig: Susanne Biers Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, da wieder ganz schön viel zusammen- Familiendrama über Lügen und Geheimnisse, liebe Filmfreunde! gekommen. An Nachschub für Ihr schmerzhafte Enthüllungen und tiefgreifenden Kaum ist Ostern vorbei, überraschen Entscheidungen ist ein Meisterwerk an Heimkino fehlt es also ganz bestimmt Inszenierung und Darstellung. wir Sie mit einer weiteren Ausgabe nicht. Unsere ganz persönlichen Favo- unseres Newsletters. Eigentlich woll- riten bei den deutschen Veröffentli- Schon lange hat sich der dänische Film von ten wir unseren Bradford-Bericht in chungen: THEM (offensichtlich jetzt Übervater Lars von Trier und „Dogma“ genau dieser Ausgabe präsentieren, emanzipiert, seine Nachfolger probieren andere doch im korrekten 1:2.35-Bildformat) Wege, ohne das Gelernte über Bord zu werfen. doch das Bilderbuchwetter zu Ostern und BUBBA HO-TEP. Zwei Titel, die Geblieben ist vor allem die Stärke des hat uns einen Strich durch die Rech- in keiner Sammlung fehlen sollten und Geschichtenerzählens, der Blick hinter die nung gemacht. Und wir haben es ge- bestimmt ein interessantes Double- Fassade, die Lust an der Brüchigkeit von nossen! Gerne haben wir die Tastatur Beziehungen. Denn nichts scheint den Dänen Feature für Ihren nächsten Heimkino- verdächtiger als Harmonie und Glück oder eine gegen Rucksack und Wanderschuhe abend abgeben würden. -

College Admissions, Rigged for the Rich

$2.75 DESIGNATED AREASHIGHER©2019 WSCE D WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13,2019 latimes.com College admissions, riggedfor therich Scheme paid coaches, faked test scores to securespots forchildren of the wealthy By Joel Rubin, Hannah Fry, Richard Winton and MatthewOrmseth When it came to getting their daughtersintocollege, actress Lori Loughlinand fashion designer J. Mossimo Giannulli were taking no chances. The wealthy,glamorous couple were determined their girls would attend USC, ahighly competitive school that offers seats only CJ Gunther EPA/Shutterstock to afractionofthe thou- WILLIAM SINGER sands of students who apply pleaded guiltyTuesdayto eachyear. racketeering and other So they turned to William charges in the scheme. Singer and the “side door” the NewportBeach busi- nessman said he had built intoUSC and otherhighly The big sought afteruniversities. Half amillion dollars later — Allen J. Schaben Los Angeles Times $400,000ofitsent to Singer FOR MILLIONS OF CALIFORNIANS who live near thecoast, the threatofrising sea levels and storms is and $100,000 to an adminis- business very real. Last year,winter stormseroded Capistrano Beach in Dana Point, causing aboardwalk to collapse. trator in USC’s vaunted ath- leticprogram —the girls were enrolled at the school. of getting Despitehaving nevercom- peted in crew,both had been ‘Massive’damagemay givencoveted slots reserved NEWSOM for rowers who were ex- accepted pected to join the school’s team. “This is wonderful news!” Experts call for TO HALT be the norm by 2100 Loughlin emailed Singer af- terreceiving word that a reforms to levelthe spotfor her second daughter playing field in a DEATH had been secured. She add- thriving industrythat Rising seas and routine storms couldbemore ed ahigh-five emoji. -

Guilty by Association: an Analysis of Shaunie O'neal's Online/On-Air

Journal of Research on Women andJournal Gender of Research 40 on Women and Gender Guilty by association: Volume 5, 40-61 © The Author(s) 2014 An analysis of Shaunie O’Neal’s Reprints and Permission: email [email protected] Texas Digital Library: online/on-air image restoration tactics http://www.tdl.org Mia Moody-Ramirez, Isla Hamilton-Short, and Kathryn Mitchell “He that lieth down with dogs shall rise up with fleas.” —Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack Abstract The growing use of social media as a source of networking has spurred a growing interest in using the medium as a tool for image repair. Broadening the application of Benoit’s image repair theory, this case study looks at the image repair tactics of Shaunie O’Neal who became a celebrity during her marriage to former NBA basketball player Shaquille O’Neal, their subse- quent divorce, and the creation of her VH1 show, Basketball Wives (BBW). Throughout the four seasons of BBW, O’Neal’s cast members perpetuated negative stereotypes of Black women such as “the angry Black woman,” “the Jezebel” and “the tragic mulatto.” While O’Neal did not exhibit these characteristics on the show, she became guilty by association. To repair her tarnished image, the reality TV actress used her Facebook and Twitter feeds and episodes of Season 4 of BBW to implement various image repair tactics. Study findings indicate episodes of a reality TV show and social media may provide a viable platform for a celebrity to repair his or her tarnished image; however, tactics must be authentic and consistent. -

Quantifying and Predicting Influence on Twitter

Retweets|but Not Just Retweets: Quantifying and Predicting Influence on Twitter A thesis presented by Evan T.R. Rosenman to Applied Mathematics in partial fulfillment of the honors requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Harvard College Cambridge, Massachusetts March 30, 2012 Abstract There has recently been a sharp uptick in interest among researchers and private firms in determin- ing how to quantify influence on the microblogging site Twitter. We restrict our attention solely to celebrities, and using data collected from Twitter APIs in February and March 2012, we ex- plore four different influence metrics for a group of 60 prominent and well-followed individuals. We find that retweet-based influence is the most significant type of influence, but other effects—like the adoption of hashtags and links|are comparable in terms of generated impressions, and are governed by fundamentally different dynamics. We use the insights from our analysis to develop predictive models of retweets, hashtag and link adoptions, and increases in follower counts. We find that, across different types of influence, the degree to which a celebrity is discussed on Twitter is an extremely useful predictor, while follower counts are comparatively less predictive. Acknowledgements This paper could not have been written without the input and support of many individuals. First and foremost, I thank Mike Ruberry for his invaluable assistance in formulating the ideas and writing the Java code that made this project possible. I thank my adviser Yiling Chen for her sage advice throughout this process, and also thank Michael Parzen and Cassandra Pattanayak for their recommendations regarding the statistical methods utilized in this paper. -

Reality, Tv, Celebrity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository REALITY / TV / CELEBRITY David Raskin A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Communication Studies. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Richard C. Cante Reader: Carole Blair Reader: Lawrence Grossberg ABSTRACT DAVID RASKIN: Reality / TV / Celebrity (Under the direction of Richard C. Cante) This research addresses the construction of personae on reality television series. Given Richard Dyer’s formulation of stardom as a balance of ordinary and extraordinary qualities, this paper seeks to understand how a reality television participant, lacking any traditional performance talent, could be articulated as extraordinary. Kenneth Burke’s concept of “mystery” as a desirability attached to objects atop a social hierarchy is used to help explicate the qualities of extraordinariness in reality TV stardom. Comparative formal analyses of three reality “star texts” delineate the differences between two women who attain limited fame and one who achieves wider stardom. It is concluded that two qualities are necessary to transcending the usual limits of reality television fame: the articulation of social power (closely tied to class); and the appearance of freedom and agency, even when under the constant surveillance of producers and camera operators. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of colleagues and friends who have informed and responded to my ideas during this writing process, but none more than Rich Cante and Scott Selberg. -

Danger, Danger

FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:37 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of May 5 - 11, 2019 Emily Watson stars in “Chernobyl” INSIDE Danger, •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 Hollywood Q&A Page14 danger • On Monday, May 6, join Soviet scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris, “The Terror”), nuclear physicist Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson, “Genius”) and head of the Bureau for Fuel and Energy of the Soviet Union Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård, “River”), as they seek to uncover the truth behind one of the world’s worst man-made catastrophes in the premiere of “Chernobyl,” on HBO. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS To advertise here GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIESBay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell We Need: SALES & SERVICE Motorsports 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:38 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry 10:30 p.m. NESN Red Sox Final Live ESPN Softball NCAA ACC Tournament NESN Baseball MLB Seattle Mariners Salem Sunday Sandown Windham (60) TNT Basketball NBA Playoffs Live Women’s Championship Live at Boston Red Sox Live GUIDE Pelham, 10:55 a.m.