NEO-ORIENTALISM in the OPERAS of TAN DUN by Nan Zhang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sold-Out Sessions to Tan Dun's the First Emperor Even Before Opera

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE More Shows for The Metropolitan Opera in HD Digital at Golden Village VivoCity Sold-out Sessions to Tan Dun’s The First Emperor even before Opera premieres tomorrow Singapore, 19 September 2007 – Due to popular and overwhelming demand, Golden Village has added 7 more shows for The Metropolitan Opera: Tan Dun’s The First Emperor in High-Definition (HD) Digital exclusively at GV VivoCity from 20 September to 3 October 2007 daily. 5 out of the original 9 sessions for The First Emperor have been fully sold out before the opera premieres tomorrow. Remaining sessions are left with tickets on the first two rows from the screen. Golden Village is now adding new sessions in response to the great demand. Opera fans who were not able to catch The Metropolitan Opera in HD Digital at GV VivoCity will now be given another chance to experience the phenomenon. Screening details: 20 – 26 September 2007 – 7pm daily and 3.30pm on the weekends 4 sessions remaining and tickets are selling fast! Golden Village Seats only available in the first two rows from the screen . VivoCity 27 September – 3 October 2007 – 7pm daily 7 new sessions added Tickets to The First Emperor are at $15 per ticket. Tickets are available at GV Box Offices and at www.gv.com.sg . Staged by world-renown film director Zhang Yimou, written by acclaimed Academy Award winner Tan Dun, The First Emperor stars Plácido Domingo (one of the Three Tenors ) as Qin Shi Huang. Please visit www.gv.com.sg for more information. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: an Autoethnography

The Qualitative Report Volume 25 Number 1 Article 7 1-13-2020 Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography Nan Zhang Monash University, Australia, [email protected] Maria Gindidis Monash University, Australia Jane Southcott Monash University, Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended APA Citation Zhang, N., Gindidis, M., & Southcott, J. (2020). Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography. The Qualitative Report, 25(1), 88-104. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4022 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography Abstract In this paper, I research how my background, in different times and within diverse spaces, has led me to exploring and working with specific Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) programs. I am forever motivated to engage students learning second languages by providing them with possibilities to find out who they are, to know other ways of being and meet diverse peoples, to maintain languages more effectively and maintain culture(s) more authentically. I employ autoethnography as a method to discover and uncover my personal and interpersonal experiences through the lens of my dance related journeys. -

Concert Program for October 22 and 23, 2009

Concert Program for October 22 and 23, 2009 David Robertson, conductor Measha Brueggergosman, soprano Kate Lindsey, mezzo-soprano Paul Groves, tenor Jubilant Sykes, baritone Saint Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director Saint Louis Symphony IN UNISON® Chorus Robert Ray, director IVES The Unanswered Question (c. 1908) (1874-1954) BARBER Adagio for Strings (1936) (1910-1981) ROLLO DILWORTH Freedom’s Plow (2009) World Premiere (b. 1970) Saint Louis Symphony IN UNISON® Chorus Robert Ray, director Intermission TIPPETT A Child of Our Time (1939-41) (1905-1998) Part I Chorus: The world turns on its dark side The Argument: Man has measured the heavens Scena: Is evil then good? Now in each nation Chorus of the Oppressed: When shall the usurers’ city cease I have no money for my bread How can I cherish my man in such days A Spiritual: Steal away Part II Chorus: A star rises in mid-winter And a time came Double Chorus of Persecutors and Persecuted: Away with them! Where they could, they fled Chorus of the Self-righteous: We cannot have them in our Empire And the boy’s mother wrote a letter Scena: O my son! A Spiritual: Nobody knows the trouble I see Scena: The boy becomes desperate in his agony They took a terrible vengeance. The Terror: Burn down their houses! Men were ashamed of what was done A Spiritual of Anger: Go down, Moses The Boy sings in his Prison: My dreams are all shattered What have I done to you, my son? The dark forces rise like a flood A Spiritual: O, by and by Part III Chorus: The cold deepens The soul of man Scena: The words of wisdom are these General Ensemble: I would know my shadow and my light A Spiritual: Deep river Measha Brueggergosman, soprano Kate Lindsey, mezzo-soprano Paul Groves, tenor Jubilant Sykes, baritone Saint Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director Saint Louis Symphony IN UNISON® Chorus Robert Ray, director David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. -

25Th Anniversary

25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award Arts Patronage Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Arts Patronage Award 1992 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 2016 Anniversary 2016 CONTENT MONTBLANC DE LA CULTURE ARTS PATRONAGE AWARD 25th Anniversary — Preface 04 / 05 The Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 06 / 09 Red Carpet Moments 10 / 11 25 YEARS OF PATRONAGE Patron of Arts — 2016 Peggy Guggenheim 12 / 23 2015 Luciano Pavarotti 24 / 33 2014 Henry E. Steinway 34 / 43 2013 Ludovico Sforza – Duke of Milan 44 / 53 2012 Joseph II 54 / 63 2011 Gaius Maecenas 64 / 73 2010 Elizabeth I 74 / 83 2009 Max von Oppenheim 84 / 93 2 2008 François I 94 / 103 3 2007 Alexander von Humboldt 104 / 113 2006 Sir Henry Tate 114 / 123 2005 Pope Julius II 124 / 133 2004 J. Pierpont Morgan 134 / 143 2003 Nicolaus Copernicus 144 / 153 2002 Andrew Carnegie 154 / 163 2001 Marquise de Pompadour 164 / 173 2000 Karl der Grosse, Hommage à Charlemagne 174 / 183 1999 Friedrich II the Great 184 / 193 1998 Alexander the Great 194 / 203 1997 Peter I the Great and Catherine II the Great 204 / 217 1996 Semiramis 218 / 227 1995 The Prince Regent 228 / 235 1994 Louis XIV 236 / 243 1993 Octavian 244 / 251 1992 Lorenzo de Medici 252 / 259 IMPRINT — Imprint 260 / 264 Content Anniversary Preface 2016 This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Montblanc Cultural Foundation: an occasion to acknowledge considerable achievements, while recognising the challenges that lie ahead. Since its inception in 1992, through its various yet interrelated programmes, the Foundation continues to appreciate the significant role that art can play in instigating key shifts, and at times, ruptures, in our perception of and engagement with the cultural, social and political conditions of our times. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

2004 OLYMPIC GAMES – Athens, Greece Men’S Results

2004 OLYMPIC GAMES – Athens, Greece Men’s results Team 1. Japan 173.821 2. United States 172.933 3. Romania 172.384 4. Korea 171.847 5. China 171.257 6. Russia 169.808 7. Ukraine 168.244 8. Germany 167.372 All-around FX PH SR VT PB HB AA 1. Paul Hamm, USA 9.725 9.700 9.587 9.137 9.837 9.837 57.823 2. Dae Eun Kim, KOR 9.650 9.537 9.712 9.412 9.775 9.725 57.811 3. Tae Young Yang, KOR 9.512 9.650 9.725 9.700 9.712 9.475 57.774 4. Ioan Silviu Suciu, ROM 9.650 9.737 9.550 9.737 9.312 9.662 57.648 5. Rafael Martinez, ESP 9.500 9.687 9.575 9.612 9.700 9.475 57.549 6. Hiroyuki Tomita, JPN 9.062 9.737 9.762 9.625 9.637 9.662 57.485 7. Yang Wei, CHN 9.600 9.725 9.737 9.512 9.800 8.987 57.361 8. Marian Dragulescu, ROM 9.612 9.525 9.562 9.850 9.437 9.337 57.323 9. Brett McClure, USA 9.412 9.712 9.162 9.625 9.725 9.612 57.248 10. Roman Zozulia, UKR 9.525 9.412 9.575 9.500 9.762 9.225 56.999 11. Isao Yoneda, JPN 9.650 9.575 9.337 9.700 9.612 9.025 56.899 12. Georgi Grebenkov, RUS 9.587 9.125 9.662 9.437 9.650 9.362 56.823 13. -

Entries WAG AARHUS 2006-AA

NOMINATIVE ENTRIES WOMEN'S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 39th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships AARHUS (DEN), 2006 Category Fed/Name Birth Yr All Around 50041 ARG DOMENEGHINI Nadir 1990 16 50044 ARG FICOSECCO Eugenia 1987 19 50042 ARG FRATANTUENO Agostina 1989 17 18058 ARG GONZALEZ Aylen 1989 17 17229 ARG POLIANDRI Sol 1988 18 50043 ARG POTOCHNIK Tatiana 1990 16 50072 AUS BONORA GEORGIA 1990 16 19316 AUS DYKES Hollie 1990 16 50071 AUS HERNANDEZ Melody 1990 16 19313 AUS JOURA Daria 1990 16 50132 AUS MORGAN Shona 1990 16 17555 AUS NGUYEN Karen 1987 19 18665 AUS VIVIAN Olivia 1989 17 16094 AUT HASENOEHRL Carina 1988 18 16095 AUT MAYER Sandra 1988 18 17068 BEL HENRY Chloé 1987 19 16890 BEL VANWALLEGHEM Aagje 1987 19 17079 BLR DMITRANITSA Liudmila 1989 17 18696 BLR LARINA Tatsiana 1989 17 17077 BLR MAKSHTAROVA Viktoria 1990 16 17075 BLR MARACHKOUSKAYA Nastassia 1990 16 13442 BLR NOVIKAVA Aksana 1987 19 50040 BLR SHAKOTS Volha 1990 16 16102 BLR SYCHEUSKAYA Alina 1988 18 50067 BRA CHAVES SANTOS Juliana 1990 16 13159 BRA COMIN Camila 1983 23 18053 BRA DA COSTA Bruna 1989 17 13160 BRA DOS SANTOS Daiane 1983 23 13161 BRA HYPOLITO Daniele 1984 22 16234 BRA SOUZA Lais 1988 18 17083 BUL GEORGIEVA Silvia 1990 16 16289 BUL HRISTOVA Veneta 1988 18 17080 BUL IOTOVA Suzana 1987 19 1097 BUL KARPENKO Victoria 1981 25 18543 BUL STANKOVA Mariana 1990 16 13386 BUL TANKOUCHEVA Nikolina 1986 20 *=Reserve gymnast Updated 29.09.2006 15:02:28 Page 1/7 NOMINATIVE ENTRIES WOMEN'S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 39th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships AARHUS (DEN), 2006 Category -

ASIAN GAMES RESULTS in ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS (Women) 1974 – 2010 by DR

ALL ASIAN GAMES RESULTS IN ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS (women) 1974 – 2010 BY DR. SALIH AL-AZAWI IRAQI GYMNASTICS FEDERATION Year Place Gold Silver Bronze 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) UZBEKISTAN(UZB) 2006 Doha (QAT) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 2002 Busan (KOR) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 1998 Bangkok (THA) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) Kazakhstan (KAZ) 1994 Hiroshima (JPN) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) Korea (KOR) 1990 Beijing (CHN) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Korea (KOR) 1986 Seoul (KOR) China (CHN) Korea (KOR) Japan (JPN) 1982 New Delhi (IND) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 1978 Bangkok (THA) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) All around All Asian Games Medallists Women Year Place Gold Silver Bronze HUANG 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) SUI Lu(CHN) TANAKA Rie(JPN) Qiushuang(CHN) HONG Su Jong 2006 Doha (QAT) HE Ning (CHN) ZHOU Zhuoru (CHN) (PRK) ZHANG Nan CHUSOVITINA Oxana 2002 Busan (KOR) KANG Xin (CHN) (CHN) (UZB) YEVDOKIMOVA Irina SUGAWARA Risa 1998 Bangkok (THA) LIU Xuan (CHN) (UZB) (JPN) 1994 Hiroshima (JPN) QIAO Ya (CHN) YUAN Kexia (CHN) MO Huilan (CHN) CHEN Cuiting KIM Gwang-Suk 1990 Beijing (CHN) LI Yifang (CHN) (CHN) (PRK) CHEN Cuiting 1986 Seoul (KOR) HUANG Qun (CHN) YU Feng (CHN) (CHN) CHEN Yongyan CHOE Jong Sil 1982 New Delhi (IND) WU Jiani (CHN) (CHN) (PRK) HO Hsiumin LIU Yachun (CHN) 1978 Bangkok (THA) (CHN) CHU Cheng (CHN) CHIANG S-Y. 1974 Tehran (IRI) NING H-L. (CHN) HSIN K-C. (CHN) (CHN) Vault All Asian Games Medallists Women Year Place Gold Silver Bronze HUANG OZAWA 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) TANAKA Rie(JPN) -

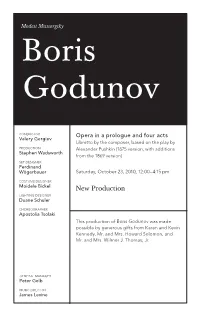

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES in ABC-CLIO’S Handbooks of World Mythology

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES IN ABC-CLIO’s Handbooks of World Mythology Handbook of Arab Mythology, Hasan El-Shamy Handbook of Celtic Mythology, Joseph Falaky Nagy Handbook of Classical Mythology, William Hansen Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch Handbook of Hindu Mythology, George Williams Handbook of Inca Mythology, Catherine Allen Handbook of Japanese Mythology, Michael Ashkenazi Handbook of Native American Mythology, Dawn Bastian and Judy Mitchell Handbook of Norse Mythology, John Lindow Handbook of Polynesian Mythology, Robert D. Craig HANDBOOKS OF WORLD MYTHOLOGY Handbook of Chinese Mythology Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright © 2005 by Lihui Yang and Deming An All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yang, Lihui. Handbook of Chinese mythology / Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner. p. cm. — (World mythology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-806-X (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57607-807-8 (eBook) 1. Mythology, Chinese—Handbooks, Manuals, etc. I. An, Deming. II. Title. III. Series. BL1825.Y355 2005 299.5’1113—dc22 2005013851 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Folktales and Other References in Toriyama's Dragon Ball

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositori d'Objectes Digitals per a l'Ensenyament la Recerca i la Cultura Folktales and Other References in Toriyama’s Dragon Ball Xavier Mínguez-López Valencia University, Spain ELCIS Group [email protected] Departament Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura Avgda. Tarongers 4 46022 València Tel. ++34 605288430 Published in Animation: an Interdisciplinary Journal, 9(1). 2014 Abstract: The aim of this article is to show the relationship between Japanese folktales and Japanese anime as a genre, especially how the intertextuality with traditional tales and myth subvert its conventional use. To meet this goal I have used Toriyama’s successful Dragon Ball series, which has enjoyed continued popularity right from its first publication in the 1980s. I analyse the parallelism between Dragon Ball and a classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West, its main source. However, there are many other folkloric references present in Dragon Ball connected to religion and folktales. The author illustrates this relationship with examples taken from the anime that correspond to the traditional Japanese Folklore but that are used with a subversive goal which makes it a rich source for analysis and for Literary Education. Keywords: animated TV series, anime, Dragon Ball, Japanese animation, Japanese folktales, Japanese religion, literary education, myth, narrative, subversion, Toriyama Corresponding Author: Xavier Mínguez López, Departament Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura, 1 Universitat de València Avgda. Tarongers 4, 46022 València, Spain. Email: [email protected] Pop culture is too pervasive, rampant, eclectic and polyglot to be unravelled and remade into an academic macramé pot holder[...] It's a cultural gulf defined by differences in view of how cultures are transforming and mutating through transnational activity.