Final Appraisal Determination: Zaleplon, Zolpidem and Zopiclone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmaceutical Starting Materials/Essential Drugs

BULLETIN MNS October 2009 PHARMACEUTICAL STARTING MATERIALS MARKET NEWS SERVICE (MNS) BI -MONTHLY EDITION Market News Service Pharmaceutical Starting Materials/Essential Drugs October 2009, Issue 5 The Market News Service (MNS) is made available free of charge to all Trade Support Institutions and enterprises in Sub-Saharan African countries under a joint programme of the International Trade Centre and CBI, the Dutch Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries (www.cbi.nl). Should you be interested in becoming an information provider and contributing to MNS' efforts to improve market transparency and facilitate trade, please contact us at [email protected]. This issue continues the series, started at the beginning of the year, focusing on the leading markets in various world regions. This issue covers the trends and recent developments in eastern European pharmaceutical markets. To subscribe to the report or to access MNS reports directly online, please contact [email protected] or visit our website at: http://www.intracen.org/mns. Copyright © MNS/ITC 2007. All rights reserved 1 Market News Service Pharmaceutical Starting Materials Introduction WHAT IS THE MNS FOR PHARMACEUTICAL STARTING MATERIALS/ESSENTIAL DRUGS? In 1986, the World Health Assembly laid before the Organization the responsibility to provide price information on pharmaceutical starting materials. WHA 39.27 endorsed WHO‟s revised drug strategy, which states “... strengthen market intelligence; support drug procurement by developing countries...” The responsibility was reaffirmed at the 49th WHA in 1996. Resolution WHA 49.14 requests the Director General, under paragraph 2(6) “to strengthen market intelligence, review in collaboration with interested parties‟ information on prices and sources of information on prices of essential drugs and starting material of good quality, which meet requirements of internationally recognized pharmacopoeias or equivalent regulatory standards, and provide this information to member states”. -

Herbal Remedies and Their Possible Effect on the Gabaergic System and Sleep

nutrients Review Herbal Remedies and Their Possible Effect on the GABAergic System and Sleep Oliviero Bruni 1,* , Luigi Ferini-Strambi 2,3, Elena Giacomoni 4 and Paolo Pellegrino 4 1 Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, Sapienza University, 00185 Rome, Italy 2 Department of Neurology, Ospedale San Raffaele Turro, 20127 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 3 Sleep Disorders Center, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, 20132 Milan, Italy 4 Department of Medical Affairs, Sanofi Consumer HealthCare, 20158 Milan, Italy; Elena.Giacomoni@sanofi.com (E.G.); Paolo.Pellegrino@sanofi.com (P.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-33-5607-8964; Fax: +39-06-3377-5941 Abstract: Sleep is an essential component of physical and emotional well-being, and lack, or dis- ruption, of sleep due to insomnia is a highly prevalent problem. The interest in complementary and alternative medicines for treating or preventing insomnia has increased recently. Centuries-old herbal treatments, popular for their safety and effectiveness, include valerian, passionflower, lemon balm, lavender, and Californian poppy. These herbal medicines have been shown to reduce sleep latency and increase subjective and objective measures of sleep quality. Research into their molecular components revealed that their sedative and sleep-promoting properties rely on interactions with various neurotransmitter systems in the brain. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that plays a major role in controlling different vigilance states. GABA receptors are the targets of many pharmacological treatments for insomnia, such as benzodiazepines. Here, we perform a systematic analysis of studies assessing the mechanisms of action of various herbal medicines on different subtypes of GABA receptors in the context of sleep control. -

The Safety Risk Associated with Z-Medications to Treat Insomnia in Substance Use Disorder Patients

Riaz U, et al., J Addict Addictv Disord 2020, 7: 054 DOI: 10.24966/AAD-7276/100054 HSOA Journal of Addiction & Addictive Disorders Review Article Introduction The Safety Risk Associated Benzodiazepine receptor agonist is divided in two categories: with Z-Medications to Treat a) Benzodiazepine hypnotics and Insomnia in Substance Use b) Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics. The prescription of Z-medications which is non-benzodiazepine Disorder Patients hypnotic is common in daily clinical practice, particularly among primary medical providers to treat patients with insomnia. This trend Usman Riaz, MD1* and Syed Ali Riaz, MD2 is less observed among psychiatrist, but does exist. While treating substance use disorder population the prescription of Z-medications 1 Division of Substance Abuse, Department of Psychiatry, Montefiore Medical should be strongly discouraged secondary to well documented Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx NY, USA safety risks. There is sufficient data available suggesting against the 2Department of Pulmonology/Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Virtua Health, prescription of Z-medications to treat insomnia in substance abuse New Jersey, USA patients. Though treating insomnia is essential in substance use disorder patients to prevent relapse on alcohol/drugs, be mindful of risk associated with hypnotics particularly with BZRA (Benzodiazepines Abstract and Non benzodiazepines hypnotics). Z-medications are commonly prescribed in clinical practices Classification of Z-medications despite the safety concerns. Although these medications are Name of medication Half-life (hr) Adult dose (mg). considered safer than benzodiazepines, both act on GABA-A receptors as an allosteric modulator. In clinical practice, the risk Zaleplon 1 5-20 profile for both medications is not any different, particularly in Zolpidem 1.5-4.5 5-10 substance use disorder population. -

Appendix D: Important Facts About Alcohol and Drugs

APPENDICES APPENDIX D. IMPORTANT FACTS ABOUT ALCOHOL AND DRUGS Appendix D outlines important facts about the following substances: $ Alcohol $ Cocaine $ GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyric acid) $ Heroin $ Inhalants $ Ketamine $ LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) $ Marijuana (Cannabis) $ MDMA (Ecstasy) $ Mescaline (Peyote) $ Methamphetamine $ Over-the-counter Cough/Cold Medicines (Dextromethorphan or DXM) $ PCP (Phencyclidine) $ Prescription Opioids $ Prescription Sedatives (Tranquilizers, Depressants) $ Prescription Stimulants $ Psilocybin $ Rohypnol® (Flunitrazepam) $ Salvia $ Steroids (Anabolic) $ Synthetic Cannabinoids (“K2”/”Spice”) $ Synthetic Cathinones (“Bath Salts”) PAGE | 53 Sources cited in this Appendix are: $ Drug Enforcement Administration’s Drug Facts Sheets1 $ Inhalant Addiction Treatment’s Dangers of Mixing Inhalants with Alcohol and Other Drugs2 $ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA’s) Alcohol’s Effects on the Body3 $ National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA’s) Commonly Abused Drugs4 $ NIDA’s Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Finding and Getting Help5 $ National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine’s Alcohol Withdrawal6 $ Rohypnol® Abuse Treatment FAQs7 $ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) Keeping Youth Drug Free8 $ SAMHSA’s Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality’s (CBHSQ’s) Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables9 The substances that are considered controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) are divided into five schedules. An updated and complete list of the schedules is published annually in Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) §§ 1308.11 through 1308.15.10 Substances are placed in their respective schedules based on whether they have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, their relative abuse potential, and likelihood of causing dependence when abused. -

Anticonvulsants Antipsychotics Benzodiazepines/Anxiolytics ADHD

Anticonvulsants Antidepressants Generic Name Brand Name Generic Name Brand Name Carbamazepine Tegretol SSRI Divalproex Depakote Citalopram Celexa Lamotrigine Lamictal Escitalopram Lexapro Topirimate Topamax Fluoxetine Prozac Fluvoxamine Luvox Paroxetine Paxil Antipsychotics Sertraline Zoloft Generic Name Brand Name SNRI Typical Desvenlafaxine Pristiq Chlorpromazine Thorazine Duloextine Cymbalta Fluphenazine Prolixin Milnacipran Savella Haloperidol Haldol Venlafaxine Effexor Perphenazine Trilafon SARI Atypical Nefazodone Serzone Aripiprazole Abilify Trazodone Desyrel Clozapine Clozaril TCA Lurasidone Latuda Clomimpramine Enafranil Olanzapine Zyprexa Despiramine Norpramin Quetiapine Seroquel Nortriptyline Pamelor Risperidone Risperal MAOI Ziprasidone Geodon Phenylzine Nardil Selegiline Emsam Tranylcypromine Parnate Benzodiazepines/Anxiolytics DNRI Generic Name Brand Name Bupropion Wellbutrin Alprazolam Xanax Clonazepam Klonopin Sedative‐Hypnotics Lorazepam Ativan Generic Name Brand Name Diazepam Valium Clonidine Kapvay Buspirone Buspar Eszopiclone Lunesta Pentobarbital Nembutal Phenobarbital Luminal ADHD Medicines Zaleplon Sonata Generic Name Brand Name Zolpidem Ambien Stimulant Amphetamine Adderall Others Dexmethylphenidate Focalin Generic Name Brand Name Dextroamphetamine Dexedrine Antihistamine Methylphenidate Ritalin Non‐stimulant Diphenhydramine Bendryl Atomoxetine Strattera Anti‐tremor Guanfacine Intuniv Benztropine Cogentin Mood stabilizer (bipolar treatment) Lithium Lithane Never Mix, Never Worry: What Clinicians Need to Know about -

Insomnia Medications – Safety Communication and Updated Labeling

Insomnia medications – Safety communication and updated labeling • On April 30, 2019, the FDA announced that a Boxed Warning will be added to the drug labels of certain common prescription insomnia medications due to rare but serious injuries occurring because of complex sleep behaviors, including sleepwalking, sleep driving, and engaging in other activities while not fully awake. — These complex sleep behaviors have also resulted in deaths. — These behaviors appear to be more common with eszopiclone (Lunesta®), zaleplon (Sonata®), and zolpidem (eg, Ambien®, Ambien CR®, Edluar®, Intermezzo®, and Zolpimist™) than other prescription medications used for sleep. — The FDA is also requiring an update to the Contraindication section of the drug labels, to avoid use of these medications in patients who have previously experienced an episode of complex sleep behavior with eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem. — This information will also be added to the patient Medication Guides. • Drugs such as eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem are prescription sedative-hypnotic medications used to treat insomnia in adults who have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep. • Patients should stop taking their insomnia medication and contact their health care professional right away if they experience a complex sleep behavior where they engage in activities while they are not fully awake or if they do not remember activities they have done while taking the medication. • Healthcare professionals should not prescribe eszopiclone, zaleplon, or zolpidem to patients who have previously experienced complex sleep behaviors after taking any of these medications. All patients should be advised that although rare, the behaviors caused by these medications have led to serious injuries or death. -

Anxiety Disorders, Insomnia, PTSD, OCD

2/3/2020 Anxiety Disorders, Insomnia, PTSD, OCD Steven L. Dubovsky, M.D. 1 2/3/2020 Basic Benzodiazepine Structure R1 R2 N C R7 C R3 C=N R4 R2′ Benzodiazepine R1 R2 R3 R7 R2′ Alprazolam Fused triazolo ring -H -Cl -H Chlordiazepoxide - -NHCH3 -H -Cl -H Clonazepam -H =O -H NO2 -Cl Diazepam -CH3 =O -H -Cl -H 2 2/3/2020 GABA-Benzodiazepine Receptor Complex GABA BZD Cl- 3 2/3/2020 Benzodiazepine Action GABA Cl- + + BZD - Cl- Inverse agonist Flumazenil • Benzodiazepine receptor antagonist R1 R2 • Therapeutic uses: C N – Benzodiazepine overdose R3 C R7 N C – Reversal of conscious sedation R4 = – Reversal of hepatic encephalopathy symptoms R2′ – Facilitation of benzodiazepine withdrawal • Can provoke withdrawal and induce anxiety 4 2/3/2020 BZD Receptor Subtypes • Type 1: Limbic system, locus coeruleus – Anxiolytic • Type 2: Cortex, pyramidal cells – Muscle relaxation, anticonvulsant, CNS depression, sedation, psychomotor impairment • Type 3: Mitochondria, periphery – Dependence, withdrawal BZD Features • Potency – High potency: Midazolam (Versed), alprazolam (Xanax), triazolam (Halcion) – Low potency: Chlordiazepoxide (Librium), flurazepam (Dalmane) • Lipid solubility – High solubility: Alprazolam, diazepam (Valium) – Low solubility: Lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium) • Elimination half-life – Long half-life: Diazepam, chlordiazepoxide – Short half-life: Alprazolam, midazolam 5 2/3/2020 Potency • High potency – Smaller dose to produce same effect – More receptor occupancy – More intense withdrawal • Low potency – Higher doses used -

Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault in the U.S

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Estimate of the Incidence of Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault in the U.S. Document No.: 212000 Date Received: November 2005 Award Number: 2000-RB-CX-K003 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. AWARD NUMBER 2000-RB-CX-K003 ESTIMATE OF THE INCIDENCE OF DRUG-FACILITATED SEXUAL ASSAULT IN THE U.S. FINAL REPORT Report prepared by: Adam Negrusz, Ph.D. Matthew Juhascik, Ph.D. R.E. Gaensslen, Ph.D. Draft report: March 23, 2005 Final report: June 2, 2005 Forensic Sciences Department of Biopharmaceutical Sciences (M/C 865) College of Pharmacy University of Illinois at Chicago 833 South Wood Street Chicago, IL 60612 ABSTRACT The term drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA) has been recently coined to describe victims who were given a drug by an assailant and subsequently sexually assaulted. Previous studies that have attempted to determine the prevalence of drugs in sexual assault complainants have had serious biases. This research was designed to better estimate the rate of DFSA and to examine the social aspects surrounding it. Four clinics were provided with sexual assault kits and asked to enroll sexual assault complainants. -

Zaleplon May Cause Serious Side Effects Including Complex S

MEDICATION GUIDE Zaleplon Capsules USP (zal’ e plon) Rx only Read this Medication Guide before you start taking zaleplon and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This Medication Guide does not take the place of talking to your doctor about your medical condition or treatment. You and your doctor should talk about zaleplon when you start taking it and at regular checkups. What is the most important information I should Zaleplon is a federally controlled substance know about zaleplon? (C-IV) because it can be abused or lead to Zaleplon may cause serious side effects dependence. Keep zaleplon in a safe place to including complex sleep behaviors that may prevent misuse and abuse. Selling or giving away cause serious injury and death. After taking zaleplon may harm others, and is against the law. zaleplon, you may get up out of bed while not Tell your doctor if you have ever abused or been being fully awake and do an activity that you dependent on alcohol, prescription medicines do not know you are doing (complex sleep or street drugs. behaviors). The next morning, you may not Who should not take zaleplon? remember that you did anything during the night. Do not take zaleplon capsules if you are allergic to These activities may occur with zaleplon whether anything in them. See the end of this Medication or not you drink alcohol or take other medicines Guide for a complete list of ingredients in zaleplon that make you sleepy. capsules. Reported activities include: Zaleplon may not be right for you. -

Sonata®(Zaleplon) Capsules CIV

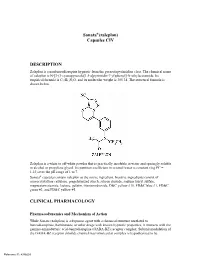

Sonata®(zaleplon) Capsules CIV DESCRIPTION Zaleplon is a nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic from the pyrazolopyrimidine class. The chemical name of zaleplon is N-[3-(3-cyanopyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7-yl)phenyl]-N-ethylacetamide. Its empirical formula is C17H15N5O, and its molecular weight is 305.34. The structural formula is shown below. Zaleplon is a white to off-white powder that is practically insoluble in water and sparingly soluble in alcohol or propylene glycol. Its partition coefficient in octanol/water is constant (log PC = 1.23) over the pH range of 1 to 7. Sonata® capsules contain zaleplon as the active ingredient. Inactive ingredients consist of microcrystalline cellulose, pregelatinized starch, silicon dioxide, sodium lauryl sulfate, magnesium stearate, lactose, gelatin, titanium dioxide, D&C yellow #10, FD&C blue #1, FD&C green #3, and FD&C yellow #5. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacodynamics and Mechanism of Action While Sonata (zaleplon) is a hypnotic agent with a chemical structure unrelated to benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or other drugs with known hypnotic properties, it interacts with the gamma-aminobutyric acid-benzodiazepine (GABA-BZ) receptor complex. Subunit modulation of the GABA-BZ receptor chloride channel macromolecular complex is hypothesized to be Reference ID: 4386603 responsible for some of the pharmacological properties of benzodiazepines, which include sedative, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant, and anticonvulsive effects in animal models. Other nonclinical studies have also shown that zaleplon binds selectively to the brain omega-1 receptor situated on the alpha subunit of the GABAA/chloride ion channel receptor complex and potentiates t-butyl-bicyclophosphorothionate (TBPS) binding. Studies of binding of zaleplon to recombinant GABAA receptors (α1β1γ2 [omega-1] and α2β1γ2 [omega-2]) have shown that zaleplon has a low affinity for these receptors, with preferential binding to the omega-1 receptor. -

High-Risk Medications in the Elderly

High-Risk Medications in the Elderly The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) contracted with the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) to develop clinical strategies to monitor and evaluate the quality of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. The NCQA’s Geriatric Measurement Advisory Panel identified several categories of medications that have an increased risk of adverse effects to elderly patients. The enclosed chart identifies several key medication categories that CMS and NCQA are monitoring. In an effort to ensure patients’ safety, many of our clients have established pre-authorization protocols for those prescriptions for high risk medications in patients older than 65 years of age. Since pharmacists have a very important role in patient care, we want you to be part of this safety initiative. We strongly encourage that you contact the prescriber when your elderly patient is requesting a new or refilled prescription of a high-risk medication listed on the below chart. Category High Risk Medications Alternatives Analgesics butalbital/APAP Mild Pain: butalbital/APAP/caffeine (ESGIC, FIORICET) acetaminophen, codeine, short-term NSAIDs butalbital /APAP/caffeine/codeine Moderate/Severe Pain: butalbital/ASA/caffeine (FIORINAL) tramadol (ULTRAM), tramadol/APAP* (ULTRACET), butalbital/ASA/caffeine/codeine morphine sulfate (MS CONTIN), ketorolac (TORADOL) hydrocodone/APAP (VICODIN, etc.), oxycodone indomethacin (INDOCIN) (OXYIR), oxycodone/APAP (PERCOCET), fentanyl meperidina (DEMEROL) patch (DURAGESIC), OXYCONTIN -

Sonata, INN-Zaleplon

authorised ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS longer no product Medicinal 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Sonata 5 mg hard capsules 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each capsule contains 5 mg of zaleplon. Excipient with known effect: Lactose monohydrate 54 mg. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Capsule, hard. Capsules have an opaque white and opaque light brown hard shell with the strength “5 mg”. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications authorised Sonata is indicated for the treatment of patients with insomnia who have difficulty falling asleep. It is indicated only when the disorder is severe, disabling or subjecting the individual to extreme distress. 4.2 Posology and method of administration longer For adults, the recommended dose is 10 mg. no Treatment should be as short as possible with a maximum duration of two weeks. Sonata can be taken immediately before going to bed or after the patient has gone to bed and is experiencing difficulty falling asleep. As administration after food delays the time to maximal plasma concentration by approximately 2 hours no food should be eaten with or shortly before intake of Sonata. product The total daily dose of Sonata should not exceed 10 mg in any patient. Patients should be advised not to take a second dose within a single night. Elderly Elderly patients may be sensitive to the effects of hypnotics; therefore, 5 mg is the recommended dose of Sonata. Medicinal Paediatric patients Sonata is contraindicated in children and adolescents under 18 years of age (see section 4.3).