Interpretive Performance Techniques and Lyrical Innovations on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Title of Document: DEPRESSION AND

ABSTRACT Title of Document: DEPRESSION AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS IN YOUNG, LOW-INCOME AFRICAN- AMERICAN MEN AND FATHERS Megan E. Fitzgerald, M.S. Directed By: Associate Professor Kevin Roy, Department of Family Science Depression is a debilitating mental illness that in its most serious form, major depression, has affected between 3.6% to 12.7% of men in the United States (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2000; Jonas, Brody, Roper, & Narrow, 2003; Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, & Nelson, 1994). It has consistently been found to be twice as prevalent in women as in men, and yet the suicide rate of men is four to five times that of women (Singh, Kochanek, & MacDorman, 1996; World Health Organization, 2005). Despite this, little is known about the experience and expression of the full range of depression in men, and specifically, young, low-income men of color who are fathers. When young fathers suffer from depression, there are enormous consequences for young families, both financial and emotional (Ansseau et al., 2008; Mirowsky & Ross, 2002; Montgomery, Cook, Bartley, & Wadsworth, 1999; Patten et al., 2006; Rehman, Gollan, & Mortimer, 2008; Soares, Macassa, Grossi, & Viitasara, 2008). It is possible that the risk for depression increases when fatherhood includes the challenges of nonresidential parenting and financial stress (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2002; Roy, 2004). This has implications for their co-parenting relationships, and shapes their identities and roles as parents and providers (Bouma, Ormel, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, 2008; Kim, Capaldi, & Stoolmiller, 2003). However, fatherhood also brings many opportunities for young men; it is a chance for them to be generative for the first time in their lives and to experience the joys that accompany the challenges of parenthood (Palkovitz, Copes, & Woolfolk, 2001). -

Marshall University Music Department Presents a Faculty Recital, Featuring, Stephen Lawson, Horn, Assisted by J

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Winter 2-10-2010 Marshall University Music Department Presents a Faculty Recital, featuring, Stephen Lawson, horn, assisted by J. Steven Hall, marimba, percussion, Kay Lawson, bassoon, Peggy Johnson, piano Stephen Lawson Marshall University, [email protected] Steven Hall Marshall University, [email protected] Kay Lawson Marshall University, [email protected] Peggy Johnson Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Stephen; Hall, Steven; Lawson, Kay; and Johnson, Peggy, "Marshall University Music Department Presents a Faculty Recital, featuring, Stephen Lawson, horn, assisted by J. Steven Hall, marimba, percussion, Kay Lawson, bassoon, Peggy Johnson, piano" (2010). All Performances. Book 523. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/523 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Music Program The Call ofBoromir Daniel McCarthy (b. 1955) MUSIC Solo Suite for Horn and Improvisatory Percussion Alec Wilder presents a I( TJ = 96) (1907~1980) II. Slow Faculty Recital III. (9 = 138) featuring Stephen Lawson, horn Interval to restage assisted by Trio for Horn, Bassoon and Piano Eric Ewazen J. Steven Hall, marimba, percussion I. Lento, Allegro agitato (b. 1954) Kay Lawson, bassoon II. Andante III. Lento, Allegro molto Peggy Johnston, piano Three American Folksongs arr. Randall E. Faust I. The Wabash Cannonball II. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

John Barrows and His Contributions to the Horn Literature Kristin Woodward

Florida State University Libraries 2016 John Barrows and His Contributions to the Horn Literature Kristin Woodward Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC JOHN BARROWS AND HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HORN LITERATURE By KRISTIN WOODWARD A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2016 Kristin Woodward defended this treatise on April 12, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Professor Michelle Stebleton Professor Directing Treatise Dr. Alice-Ann Darrow University Representative Dr. Jonathan Holden Committee Member Dr. Christopher Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank several people who were instrumental in helping with this project. The staff at the Mills Music Library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was incredibly kind and patient while helping me research information about John Barrows. Because of their help, I was able to view scans of many of John Barrows’ manuscripts and to access several recordings which were otherwise unavailable to me. Thank you to my committee for being supportive of me during my time at Florida State and a special thank you to Professor Michelle Stebleton for encouraging me when I needed it the most and for pushing me to be the finest horn player, musician, and woman I can be. Thank you also to my parents who taught me that, through hard work and perseverance, I can always reach my goals. -

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021)

Discography Updates (Updated May, 2021) I’ve been amassing corrections and additions since the August, 2012 publication of Pepper Adams’ Joy Road. Its 2013 paperback edition gave me a chance to overhaul the Index. For reasons I explain below, it’s vastly superior to the index in the hardcover version. But those are static changes, fixed in the manuscript. Discographers know that their databases are instantly obsolete upon publication. New commercial recordings continue to get released or reissued. Audience recordings are continually discovered. Errors are unmasked, and missing information slowly but surely gets supplanted by new data. That’s why discographies in book form are now a rarity. With the steady stream of updates that are needed to keep a discography current, the internet is the ideal medium. When Joy Road goes out of print, in fact, my entire book with updates will be posted right here. At that time, many of these changes will be combined with their corresponding entries. Until then, to give you the fullest sense of each session, please consult the original entry as well as information here. Please send any additions, corrections or comments to http://gc-pepperadamsblog.blogspot.com/, despite the content of the current blog post. Addition: OLIVER SHEARER 470900 September 1947, unissued demo recording, United Sound Studios, Detroit: Willie Wells tp; Pepper Adams cl; Tommy Flanagan p; Oliver Shearer vib, voc*; Charles Burrell b; Patt Popp voc.^ a Shearer Madness (Ow!) b Medley: Stairway to the Stars A Hundred Years from Today*^ Correction: 490900A Fall 1949 The recording was made in late 1949 because it was reviewed in the December 17, 1949 issue of Billboard. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Bob James Three Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Three mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Three Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1301 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1416 mb WMA version RAR size: 1546 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 503 Other Formats: VQF MMF MP2 AA WAV AU ADX Tracklist Hide Credits One Mint Julep 1 9:09 Composed By – R. Toombs* Women Of Ireland 2 8:06 Composed By – S. Ó Riada* Westchester Lady 3 7:27 Composed By – B. James* Storm King 4 6:36 Composed By – B. James* Jamaica Farewell 5 5:26 Composed By – L. Burgess* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Tappen Zee Records, Inc. Licensed From – Castle Communications PLC Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Remastered At – CBS Studios, New York Credits Bass – Gary King (tracks: 1, 2, 5), Will Lee (tracks: 3, 4) Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor* Bass Trombone, Tuba – Dave Bargeron Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Drums – Andy Newmark (tracks: 1), Harvey Mason (tracks: 2 to 5) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute – Hubert Laws, Jerry Dodgion Flute, Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Daniels Guitar – Eric Gale (tracks: 2 to 4), Hugh McCracken (tracks: 2 to 4), Jeff Mironov (tracks: 1) Harp – Gloria Agostini Keyboards – Bob James Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Photography By [Cover] – Richard Alcorn Producer – Creed Taylor Remastered By – Stew Romain* Supervised By [Re-mastering] – Joe Jorgensen Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone, Tin Whistle – Grover Washington, Jr. Trombone – Wayne Andre Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Frederick Buldrini, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Lewis Eley, Matthew Raimondi, Max Ellen Notes Originally released in 1976. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

Omer Avital Ed Palermo René Urtreger Michael Brecker

JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM special feature BEST 2014OF ICP ORCHESTRA not clowning around OMER ED RENÉ MICHAEL AVITAL PALERMO URTREGER BRECKER Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 JANUARY 2015—ISSUE 153 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Omer Avital by brian charette Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Ed Palermo 7 by ken dryden [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : ICP Orchestra 8 by clifford allen [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : René Urtreger 10 by ken waxman Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Michael Brecker 10 by alex henderson VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Smoke Sessions 11 by marcia hillman [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, CD Reviews 14 Katie Bull, Tom Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Special Feature: Best Of 2014 28 Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Miscellany Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Robert Milburn, Russ Musto, Event Calendar 44 Sean J. O’Connell, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman As a society, we are obsessed with the notion of “Best”. -

Program Notes Pima Community College Recital Hall April 17, 2014 7:00 PM Mark Nelson, Tuba Marie Sierra, Piano

Mark Nelson Tuba Recital Program Notes Pima Community College Recital Hall April 17, 2014 7:00 PM Mark Nelson, tuba Marie Sierra, piano Performers Marie Sierra is a professional pianist who performs collaboratively in over 40 concerts annually and is formerly the staff pianist for the Tucson Girls Chorus and currently the staff pianist for the Tucson Boys Chorus. Recently, Marie has performed and recorded with Artists Michael Becker (trombone) and Viviana Cumplido (Flute). She has also recorded extensively with Yamaha Artist and Saxophonist, Michael Hester, on Seasons and An American Patchwork. Marie is in demand as an accompanist throughout the United States and Mexico. Additionally, she has performed at numerous international music conferences, including the 2010 International Tuba Euphonium Conference in Tucson. Marie has served on the faculties of the Belmont University in Nashville, and the Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University. Ms. Sierra earned her Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree in Piano Performance at the University of Miami. Program Six Romances Without Words, op. 76 by Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) arranged by Ralph Sauer Published by Cherry Classics Music. www.Cherry-Classics.com. The Six Romances Without Words was originally a piano work written in 1893-1894. Like many works of the time, it would typically be played for small audiences in a parlor or small hall. The melodies are all fitting for the tuba and the harmonies are interesting but not too modern. The arranger, Ralph Sauer, has placed the movements in a different order than the original work to facilitate more of a grand finale than a reflective last movement. -

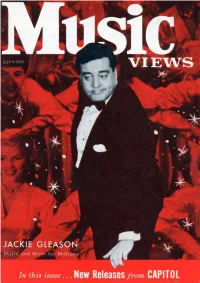

In This Issue... New Releases from CAPITOL the C O VER Music Views There Are Very Few People in July, 1955 Voi

In this issue... New Releases from CAPITOL THE C O VER Music Views There are very few people in July, 1955 Voi. XIII, No. 7 this country who have not come into contact with a TV set. There are even fewer who do not VIC ROWLAND .... Editor have access to a phonograph. Associate Editors: Merrilyn Hammond, Anyone who has a nodding ac Dorothy Lambert. quaintance with either of these appliances is sure to be fa miliar with either Jackie Gleason the comedian, Jackie Gleason GORDON R. FRASER . Publisher the musician, or both. This lat ter Jackie Gleason, the musi Published Monthly By cian, has recently succeeded in coming up with a brand new CAPITOL PUBLICATIONS, INC. sound in recorded music. It's Sunset and Vine, Hollywood 28, Calif. found in a new Capitol album, Printed in U.S.A. "Lonesome Echo." For the full story, see pages 3 to 5. Subscription $1.00 per year. A regular musical united nations is represented by lady and gentlemen pictured above. Left to right they are: Louis Serrano, music columnist for several South American magazines; Dean Martin, whose fame is international; Line Renaud, French chanteuse recently signed to Cap itol label; and Cauby Peixoto, Brazilian singer now on Columbia wax. 2 T ACKIE GLEASON has indeed provided mirth strument of lower pitch), four celli, a marim " and music to millions of people. Even in ba, four spanish-style guitars and a solo oboe. the few remaining areas where television has Gleason then selected sixteen standard tunes not as yet reached, such record albums as which he felt would lend themselves ideally "Music For Lovers Only" and other Gleason to the effect he had in mind.