The Old-Time Radio Era, Sometimes Referred to As the Golden Age of Radio, Was an Era of Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSC Old Time Radio

The RUSC Guide to Old Tim e Radio Contents Introduction ........................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 – Old Time Radio................................................. 7 When was the first radio show broadcast? ............................ 8 AT&T lead the way............................................................ 10 NBC – The Granddaddy..................................................... 11 CBS – The New Kid on the Block...................................... 11 MBS – A different way of doing things.............................. 12 The Microsoft Effect.......................................................... 13 Boom & Bust..................................................................... 13 Where did all the shows go?............................................... 14 Are old radio show fans old?.............................................. 16 Chapter 2 - Old radio show genres ..................................... 17 Comedy ............................................................................. 18 Detective............................................................................ 20 Westerns ............................................................................ 21 Drama................................................................................ 22 Juvenile.............................................................................. 24 Quiz Shows........................................................................ 26 Science Fiction.................................................................. -

Marvin Hamlisch

tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE MUSIC OF MARVIN HAMLISCH Monday, October 19, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress was established in 1992 by a bequest from Mrs. Gershwin to perpetuate the name and works of her husband, Ira, and his brother, George, and to provide support for worthy related music and literary projects. "LIKE" us at facebook.com/libraryofcongressperformingarts loc.gov/concerts Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Monday, October 19, 2015 — 8 pm tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE mUSIC OF MARVIN hAMLISCH WHITNEY BASHOR, VOCALIST | CAPATHIA JENKINS, VOCALIST LINDSAY MENDEZ, VOCALIST | BRYCE PINKHAM, VOCALIST -

334 XIII. Revivals and Recreations; The

XIII. Revivals and Recreations; The Sociology of Jazz By the early 1970s, as we have seen, jazz was in a state of stylistic chaos. This was one reason why the first glimmers of “smooth jazz” came about as both an antidote to fusion and an answer to “outside jazz.” But classical music was also in a state of chaos. The majority of listen- ers had become sick of listening to the modern music that had come to dominate the field since the end of World War II and had only become more abrasive and less communicative to a lay audience. In addition, the influx of young television executives in that period had not only led to the cancellation of many well-loved programs who they felt only appealed to an older audience demographic, but also the chopping out of virtually all arts programming. Such long-running programs as The Voice of Firestone and The Bell Telephone Hour were already gone by then. Leonard Bernstein had been replaced at the New York Philharmonic by Michael Tilson Thomas, an excellent conductor but not a popular communicator, and thus CBS’s “Young People’s Con- certs” no longer had the same appeal. In addition, both forms of music, classical and jazz, were the victims of an oil shortage that grossly affected American pressings of vinyl LPs. What had once been a high quality market was now riddled with defective copies of discs which had blis- ters in the vinyl, scratchy-sounding surfaces and wore out quickly. Record buyers who were turned off by this switched to cassette tapes or, in some cases, the new eight-track tape format. -

Radioclassics.Com June 28Th

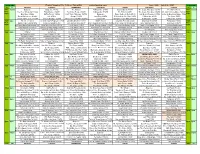

SHOW TIME RadioClassics (Ch. 148 on SiriusXM) radioclassics.com June 28th - July 4th, 2021 SHOW TIME PT ET MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY PT ET 9pm 12mid Suspense Suspense 9/16/42 The Whistler X-Minus One 2/15/56 Boston Blackie 7/9/46 The Couple Next Door 1/21/58 The Aldrich Family 9pm 12mid Prev You Were Wonderful 11/9/44 Philip Marlowe 7/28/51 Two Smart People 9/30/51 X-Minus One 7/14/55 The Falcon 6/20/51 The Couple Next Door 1/22/58 Mr. Aldrich Cooks Dinner 12/8/48 Prev Night Night Blue Eyes 8/29/46 Duffy's Tavern 1/25/44 Can't Trust A Stranger 7/27/52 Gunsmoke Fibber McGee & Molly 9/5/39 Jack Benny Program 2/17/52Detention Or Basketball Game 10/28/48 Great Gildersleeve 9/18/46 Life of Riley Escape 7/12/53 Last Fling 2/20/54 Phil Harris & Alice Faye 3/2/52 X-Minus One 4/3/56 The Chase 5/4/52 Jack Benny Program 11/16/47 Cissie's Marriage 3/24/50 I Was Communist/FBI 10/29/52 Cara 5/1/54 Going To Vegas Without Frankie X-Minus One 1/23/57 X-Minus One 6/27/57 11pm 2am The Green Hornet Screen Director's Playhouse 3/31/50 Our Miss Brooks 11/13/49 Duffy's Tavern Columbia Presents Corwin Dimension X 5/13/50 Fort Laramie 9/9/56 11pm 2am Prev Murder Trips A Rat 9/19/42 Academy Award Theatre Jack Carson Show 4/2/47 Susan Hayward & Frank Buck 7/25/43American Trilogy Carl Sandberg 6/6/44 Inner Sanctum Mysteries Gunsmoke 6/15/58 Prev Night Night Green Hornet Goes Underground 10/3/43Hold Back The Dawn 7/31/46 Lum & Abner 1/19/43 Guest: Shelley Winters 2/16/50 An American Gallery 1960s Death In The Depths 2/6/45 Command Performance -

June 1-3,2(>(>7

Leonard A. Anderson M. Seth Reines Executive Director Artistic Director June 1-3,2(>(>7 nte Media -I1 I - I , ,, This program is partially supportec grant from the Illinois Arts Council. Named a Partner In Excellence by the Illinois Arts Council. IF IT'S GOT OUR NAME ON IT YOlU'VE GOT OUR WORD ON If. attachments that are tough enough for folks Ib you. And then we put wr gllarantee on m,m, In fact,we ofb the WustryS only 3-year warm&, Visit mgrHd.com. Book By James Goldman Music Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Produced Originally on Broadway by Harold Prince By special arrangement with Cameron Mackintosh Directed & Staged by Tony Parise Assistant To The Directorr AEA Stage Manager Marie Jagger-Taylor* Tom Reynolds* Lighting Designer Musical Director Sound Designer Joe Spratt P. Jason Yarcho David J. Scobbie The Cast (In Order of Appearance) Dimitri Weismann .............................................................................................Guy S. Little Jr.* Roscoe....................................................................................................................... Tom Bunfill Phyllis Rogers Stone................................................................................... Colleen Zenk Pinter* Benjamin Stone....................................................................................................... Mark Pinter* Sally Durant Plumrner........................................................................................ a McNeely* Buddy Plummer........................................................................................................ -

State Dinners - 5/8/75 - Singapore” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 31, folder “State Dinners - 5/8/75 - Singapore” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Revised (Pg. 2} May 8, 1975 10:00 a.m. THE WHIT£ HOUSE. WASHINGTON DINNER IN HONOR OF HIS EXCELLENCY THE PRIME MINISTER OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE AND MRS. LEE May 8, 1975 8:00 p. m. Dress: Black tie ... long dresses for the ladies Arrival: 8:00 p. m .... at North Portico Entrance ... Prime Minister and Mrs. Lee, Ambassador and Mrs. Catto You and Mrs. Ford will greet Photo coverage of greeting Yellow Oval Room: Secretary and Mrs. Kissinger; His Excellency Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Si~gapore; His Excellency The Ambassador of the Republic of Singapore and Mrs. Monteiro will assemble just prior to the 8: 00 p. m. arrival of Prin1e Minister and Mrs. Lee and Ambassador and Mrs. -

Citizen Kane – Page 1 Th 75 ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S EDITION INCLUDING EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTABLES

Citizen Kane – Page 1 th 75 ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S EDITION INCLUDING EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTABLES “A film that gets better with each renewed acquaintance” Time Out CITIZEN KANE Starring Orson Welles th TM 75 Anniversary Edition Bluray out 2nd May Includes special commentaries, interviews and more! On May 2nd 2016, Warner Bros. Home Entertainment (WBHE) will release the 75th Anniversary BlurayTM edition of the Orson Welles classic CITIZEN KANE. This new 4k restoration BlurayTM comes with a set of collectables including; 5 x One Sheet/ Lobby Card reproductions, a 48page book with photos, storyboards and behind the scenes info, a 20page 1941 souvenir programme reproduction and 10 x production memos and correspondence. The Oscar®*winning film, directed, written by and starring Orson Welles, is considered to be one of the finest achievements in cinema and last year topped the BBC Culture poll of the 100 Greatest American Films. Welles was only 25 years old when he made this, his debut film, a gripping drama which would cement his reputation as one of Hollywood’s most influential directors and stars. *1942 Academy Awards Best Writing, Original Screenplay Herman J. Mankiewicz, Orson Welles Citizen Kane – Page 2 With a cast including Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead and Everett Sloane, Oscarnominated camerawork by Gregg Toland (Wuthering Heights, The Grapes of Wrath), and featuring a debut score by Bernard Herrmann (Psycho, Taxi Driver) this is a film that Time Out says “still amazes and delights”. ABOUT THE FILM 1940. Alone at his fantastic estate known as Xanadu, 70yearold Charles Foster Kane dies, uttering only the single word Rosebud. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

Lorin Hollander

Lorin Hollander Lorin Hollander (born July 19, 1944) is an American Rudolf in 1966 presented by the Department of State.[13] classical concert pianist. He has performed with virtually His appearances in Europe began in 1965, when he all of the major symphony orchestras in the United States made a recording in London of Aram Khachaturian's pi- and many around the world.[1] A New York Times critic ano concerto and Ernest Bloch's Scherzo Fantasque with has called him, “the leading pianist of his generation.”[2] the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor André Previn. In 1968 he debuted with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Among many others, Hollander has per- formed with the orchestras of Boston, Chicago, Cleve- 1 Early life land, Dallas, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, Philadel- phia, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Washington’s Na- Lorin Hollander was born in New York City into a Jewish tional Symphony, and internationally with the London family. His father, Max Hollander, was associate concert- Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw, Orchestre de la Su- master of the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo isse Romande, Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, ORTF Toscanini.[1] Lorin Hollander was a child prodigy and and New Tokyo Philharmonic.[12] gave his first public performance at age five playing ex- In 1969, Lorin Hollander gave the first public classical cerpts of Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, and at age recital using the Baldwin Electric Concert Grand at the eleven, he made his Carnegie Hall debut with the National Fillmore East.[14] In 1971 he was the first classical pianist Orchestral Association.[1][3] to give street concerts in East Harlem and in Queens, un- He studied with Eduard Steuermann[4] from age eight and der the auspices of the Department of Cultural Affairs.[15] took courses at what is now the Juilliard Pre-College at Hollander premiered Norman Dello Joio's “Fantasy and age eleven. -

CBS, Rural Sitcoms, and the Image of the South, 1957-1971 Sara K

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971 Sara K. Eskridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Eskridge, Sara K., "Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3154. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RUBE TUBE: CBS, RURAL SITCOMS, AND THE IMAGE OF THE SOUTH, 1957-1971 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Sara K. Eskridge B.A., Mary Washington College, 2003 M.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 May 2013 Acknowledgements Many thanks to all of those who helped me envision, research, and complete this project. First of all, a thank you to the Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, where I found most of the secondary source materials for this dissertation, as well as some of the primary sources. I especially thank Joseph Nicholson, the LSU history subject librarian, who helped me with a number of specific inquiries. -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022. -

Radioclassics (Ch. 148 on Siriusxm) Radioclassics.Com February 25Th

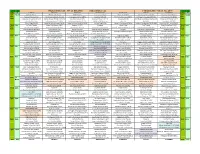

SHOW TIME RadioClassics (Ch. 148 on SiriusXM) radioclassics.com February 25th - March 3rd, 2018 SHOW TIME PT ET SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY PT ET 9pm 12mid Lux Radio Theatre CBS Radio Workshop Duffy's Tavern I Love Lucy 2/26/52 Mail Call 6/25/45 Alan Young Show 8/21/45 Academy Award Theater 9pm 12mid Prev National Velvet 2/3/47 The Record Collectors 4/27/56 The Singing Detective 4/6/51 Suspense 11/17/49 Phil Harris Alice Faye 1/18/53 Jeff Regan, Investigator 8/6/50 My Sister Eileen 5/18/46 Prev Night Night Cavalcade of America 3/21/50 Damon Runyon Theater 10/30/49 New Floor Show 4/13/51 Bob Hope Show 11/12/46 Suspense 9/2/48 Richard Diamond, Private Detective 2/9/51 Screen Guild Theatre 1/6/47 Burns & Allen Show Jack Benny Program 2/10/52 Jack Benny Program 2/11/51 Phil Harris & Alice Faye Lights Out Harry Nile Sam Spade 10/24/48 Movie Mogul 8/5/40 Abbott & Costello Show 2/26/46 Fibber McGee & Molly 11/10/42 The Lost Ring 1/9/49 Immortal Gentleman 6/14/39 Trouble Is My Beeswax 10/11/2009 Have Gun, Will Travel 3/13/59 11pm 2am Lux Radio Theater Screen Guild Players 1/8/45 Dragnet 11/15/51 Suspense Johnny Dollar Ford Theater Dinah Shore Show 5/3/45 11pm 2am Prev Treasure Island 1/29/51 Bing Crosby Show 3/21/54 Gangbusters 1/21/50 A Guy Gets Lonely 4/5/45 Matter Of...Medium Well Done 5/14/56 Double Indemnity 10/15/48 Martin & Lewis Show 10/5/51 Prev Night Night Sherlock Holmes 8/9/2001 Gunsmoke 11/7/53 Behind The Mike Seeds Of Disaster 10/15/61 Dragnet Jack Benny Program 3/8/42 Suspense 5/5/52 Richard Diamond