Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and the Changing Arab Information Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapping the Arab Spring

Rapping the Arab Spring SAM R. KIMBALL UNIS—Along a dusty main avenue, past worn freight cars piled on railroad tracks and Tyoung men smoking at sidewalk cafés beside shuttered shops, lies Kasserine, a town unremarkable in its poverty. Tucked deep in the Tunisian interior, Kasserine is 200 miles from the capital, in a region where decades of neglect by Tunisia’s rulers has led ANE H to a state of perennial despair. But pass a prison on the edge of town, and a jarring mix of neon hues leap from its outer wall. During the 2011 uprising against former President Zine El-Abdine Ben Ali, EM BEN ROMD H prisoners rioted, and much of the wall was destroyed HIC in fighting with security forces. On the wall that re- 79 Downloaded from wpj.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on December 16, 2014 REPORTAGE mains, a poem by Tunisian poet Abu al in it for fame. But one thing is certain— Qassem Chebbi stretches across 800 feet the rebellions that shook the Arab world of concrete and barbed wire, scrawled in tore open a space for hip-hop in politics, calligraffiti—a style fusing Arabic callig- destroying the wall of fear around freedom raphy with hip hop graffiti—by Tunisian of expression. And governments across the artist Karim Jabbari. On each section of region are now watching hip-hop’s advance the wall, one elaborate pattern merges into with a blend of contempt and dread. a wildly different one. “Before Karim, you might have come to Kasserine and thought, PRE-ARAB SPRING ‘There’s nothing in this town.’ But we’ve “Before the outbreak of the Arab Spring, got everything—from graffiti, to break- there was less diversity,” says independent dance, to rap. -

Star Academy Middle School Guide 2021 - 2022 PROGRAM and SCHEDULE

Star Academy Middle School Guide 2021 - 2022 PROGRAM AND SCHEDULE Capture Curiosity. Develop Potential. Our Philosophy The best for you & your growing child Our goal is to maximize your children’s academic opportunities during school time, so that families can have their evenings and weekends free to enjoy being together. The Directors of Star Academy have the child’s interests in mind, and also value the interests of the parents. Our extensive school curriculum exposes the children to many different spheres of knowledge and experiential learning during the daytime -- prime time for learning. As a result, many extraneous after school activities become unnecessary. However for those still looking for additional electives, the after school program has ample offerings all under one roof. Thus, we take away the burden of shuffling schedules, circuitous driving, and no family time or weekend time to yourselves. Mission Statement The Star Academy’s primary objective is to capture a child’s natural curiosity and to develop his/her potential as a lifelong learner. Our educational goals are based on our thoughtfully planned recognition of what the parents need for their children and what children need to succeed. Our Philosophy Each child carries tremendous potential within. Our goal at Star Academy is to gently lead each child to realize their innate potential at the highest degree. We teach children to problem solve, develop their social skills, and to steer their natural curiosity toward true knowledge. We strive to accomplish this through: -

Academy a World-Class Education

Helping good parents raise better kids.™ ParentsNovember 2019 Guideof Las Vegas Coral Academy A World-Class Education INSIDE: Lazy Dog Teams Up With Habitat for Humanity Erth’s Prehistoric Aquarium Adventure How to Make Home(work) For Your Child FREE YOUR CHILD’S JOURNEY BEGINS HERE. Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas (CASLV) believes in Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas (CASLV) believes in empowering our community by investing in our youth. empowering our community by investing in our youth. We foster an environment based on 21st Century skills: CWe foster an environment based on 21st Century skills: CCollaboration, Critical Thinking, Communication and Creativity. Collaboration, Critical Thinking, Communication and Creativity. When students are free to think and dream, anything can be When students are free to think and dream, anything can be accomplished. Applications to this award-winning school being accomplished. Applications to this award-winning school being accepted now through February 28, 2019. accepted now through February 28, 2019. Apply online: www.caslv.org/admission NELLIS AIR FORCE CENTENNIAL HILLS TAMARUS CAMPUS EASTGATE CAMPUS WINDMILL CAMPUS SANDY RIDGE BASENELLIS CAMPUS AIR FORCE CAMPUSCENTENNIAL HILLS GradesTAMARUS : K-3 CAMPUS GradesEASTGATE : K-7 CAMPUS GradesWINDMILL : 4-6 CAMPUS CAMPUSSANDY RIDGE CAMPUS GradesBASE :CAMPUS PreK-8 GradesCAMPUS : K-8 8185Grades Tamarus : K-3 St. 7777Grades Eastgate : K-7 Rd. 2150Grades Windmill : 4-6 Pkwy. Grades : 7-12 Grades : PreK-8 Grades : 7-12 42 Baer Dr. 7951Grades Deer : K-8 Springs Way. Las8185 Vegas, Tamarus NV 89123St. 7777 Eastgate Rd. Henderson,2150 Windmill NV Pkwy.89074 1051 Sandy Ridge Ave. Henderson, NV 89011 1051 Sandy Ridge Ave. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

American Idol S3 Judge Audition Venue Announcement 2019

Aug. 5, 2019 TELEVISION’S ICONIC STAR-MAKER ‘AMERICAN IDOL’ HITS THE RIGHT NOTES LUKE BRYAN, KATY PERRY AND LIONEL RICHIE TO RETURN FOR NEW SEASON ON ABC Twenty-two City Cross-Country Audition Tour Kicked Off on Tuesday, JuLy 23, in BrookLyn, New York Bobby Bones to Return as In-House Mentor In its second season on ABC, “American Idol” dominated Sunday nights and claimed the position as Sunday’s No. 1 most social show. In doing so, the reality competition series also proved that untapped talent from coast to coast is still waiting to be discovered. As previously announced, the star-maker will continue to help young singers realize their dreams with an all-new season premiering spring 2020. Returning to help find the next singing sensation are music industry legends and all-star judges Luke Bryan, Katy Perry and Lionel Richie. Multimedia personality Bobby Bones will return as in-house mentor. The all-new nationwide search for the next superstar kicked off with open call auditions in Brooklyn, New York, and will advance on to 21 additional cities across the country. In addition to auditioning in person, hopefuls can also submit audition videos online or show off their talent via Instagram, Facebook or Twitter using the hashtag #TheNextIdol. “‘American Idol’ is the original music competition series,” said Karey Burke, president, ABC Entertainment. “It was the first of its kind to take everyday singers and catapult them into superstardom, launching the careers of so many amazing artists. We couldn’t be more excited for Katy, Luke, Lionel and Bobby to continue in their roles as ‘American Idol’ searches for the next great music star, with more live episodes and exciting, new creative elements coming this season.” “We are delighted to have our judges Katy, Luke and Lionel as well as in-house mentor Bobby back on ‘American Idol,’” said executive producer and showrunner Trish Kinane. -

I-Star Academy MAGAZINE

1 2 0 2 B E F - 2 O N E U S S I i-star Academy M A G A Z I N E H E L L O I S S U E 2 P3-4) Interview with Charlotte Earl P5) Colouring Page P6) Guess who?? P7) Dance Q&A P8) Coaches Throwbacks P9) i-star Crossword P10-11) Interview with Sky Flow Artist P12) Family Fitness P13) Dance Wordsearch P14) RG Q&A P15) Design your own leotard P16) Medal Cookies Interview with Charlotte Earl Introduce us to yourself ... Hello, I'm Charlotte Earl. I am a professional circus artist living in London. How long did you train at i- star Academy? I trained at i-star Academy for about 15 years from the age of 4 up until 19 before I moved to London to join the National Centre for Circus Arts. What was your biggest achievement whilst training as a gymnast/dancer at i-star Academy? What has been your most I think my biggest memorable job as a trapeze achievements as a dancer and artist? gymnast at I-Star Academy My most memorable job as an were 1) coming 2nd as a team aerialist would be opening the at the Dance World 2019 Brit Awards live at the O2 Championships in New York arena alongside Huge Jackman 2015 and 2) medaling at the while I was still a student at the British Championships as a National Centre for Circus Arts. group gymnast and the English Champions when I was younger as an individual gymnast. -

Conventional School Index

Conventional School Index School Name County A Little Class School New Hanover ABC Christian Learning Center Robeson Abney Chapel Christian School Cumberland Abundant Life Christian Academy Orange Academy of Asheville (South) Buncombe Academy of Asheville (West) Buncombe Academy of Hope Johnston Acclaim Academy of Davidson Mecklenburg Achievement School Wake Adonai Christian Academy Buncombe Adventist Christian Academy Mecklenburg Adventist Christian School Cumberland Adventures Academy Cabarrus Agape Corner School Durham Ahoskie Christian School Hertford Al-Iman School Wake Alamance Christian School Alamance Albemarle School Pasquotank Albemarle SDA School Stanly Alexander Children's Center Mecklenburg All Saints Catholic School Mecklenburg Altapass Christian School Mitchell Ambassador Baptist Academy Cleveland Anami Montessori School Mecklenburg Anchor Baptist Academy Transylvania Anderley Academy Watauga Angels Christian Academy Mecklenburg Annunciation Catholic School Craven Apostolic Christian Academy Brunswick Appalachian Christian School Watauga Arden Christian School Buncombe Arendell Parrott Academy Lenoir Artgarden Montessori School Orange Arthur Morgan School Yancey Ashe County Christian Ac. Ashe Asheville Catholic School Buncombe Asheville Christian Academy Buncombe Asheville School Buncombe Asheville Wesleyan Christian Academy Buncombe Asheville-Pisgah Church Sch. Buncombe Assembly of Faith Chr. Sch. Gaston B'nai Shalom Day School Guilford Baldwin Chapel SDA School Guilford Ballinger Academy Guilford School Name County Barium -

19-20 KIPP MN VOA Annual Report

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Table of Contents Verification of Statutory Compliance ...............................................................................................3 Report Introduction...........................................................................................................................4 Authorizer..........................................................................................................................................6 School Board Governance ...............................................................................................................13 School Management .......................................................................................................................16 School Staffing Information & Professional Development.............................................................18 School Enrollment and Student Attrition .......................................................................................24 School Academic Performance........................................................................................................25 Finances............................................................................................................................................29 Innovative Practices ........................................................................................................................32 Service Learning ..............................................................................................................................34 -

Link up Mon Etoile

7. LINKUP : Mon étoile Niveaux : Thèmes : Elémentaire (é), intermédiaire (i) Le destin, les prédictions. Objectifs : Expression orale : raconter une histoire ; donner son opinion, argumenter. Expression écrite : rédiger une définition ; écrire un horoscope. 1. Mise en route (é)(i) Trouvez des expressions avec le mot « étoile » en français. Recherchez ensuite des expressions dans votre langue et expliquez leur signification. 2. Avec le clip (é)(i) Visionner le clip. A deux. Faites attention aux étoiles et complétez le tableau suivant. Qui a cette étoile ? Où se trouve la personne qui possède l’étoile ? Etoile n°1 Etoile n°2 Etoile n°3 Etoile n°4 Mise en commun. (i) Où se trouvent les jeunes ? Décrivez le quartier, les bâtiments. Qui sont ces jeunes ? Imaginez leur adolescence. 3. Avec les paroles (é)(i) A deux : d’après vous, à qui parle Matthieu ? Quelles sont les cicatrices auxquelles il fait référence ? Quel est le « beau chemin » dont il parle ? Imaginez l’histoire reliée à cette chanson. Mise en commun. 4. Expression orale (é) Quelles sont les couleurs signe d’espoir, de tristesse, d’amour, de calme dans votre pays ? En France ? (é)(i) En petits groupes : lisez-vous souvent votre horoscope ? Avez-vous déjà consulté une voyante ? Croyez-vous à la lecture des lignes de la main, au marc de café, à la boule de cristal,… ? Croyez-vous aux porte-bonheur, possédez-vous un objet fétiche ? (i) « Les rêves ont ce grand pouvoir de changer les couleurs du noir ». Partagez-vous cette opinion ? 5. Expression écrite (é) A deux : écrivez votre dictionnaire des couleurs. -

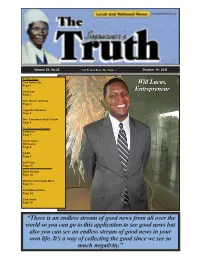

The Juice by Michael Hayes Minister of Culture If You Ask the Average Lo- Support Local Talent Unless Actually Have a Good 9

Volume 20, No.26“And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” October 19, 2011 In This Issue This Strikes Us … Will Lucas, Page 2 Will Lucas, Perryman EntrepreneurEntrepreneur Page 3 Sen. Brown onChina Page 4 Legends Weekend Page 5 Sec. Commerce Vists Toledo Page 6 The Economy Section Patterson Page 7 Cover Story: Will Lucas Page 8 GLAD Page 9 Ask Yvon Page 10 Book Review Page 12 Minister and Charlie Mack Page 13 BlackMarketPlace Page 14 Classifieds Page 15 “There is an endless stream of good news from all over the world so you can go to this application to see good news but also you can see an endless stream of good news in your own life. It’s a way of collecting the good since we see so much negativity.” Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth October 19, 2011 This Strikes Us … Community Calendar A Sojourner’s Truth Editorial October 12-31 “There are three kinds of lies,” said Mark Twain who was quoting, or so he Register for Free Tutoring: The Norman and Louise Jones Foundation; Math, said, Britain’s Benjamin Disraeli. “Lies, damned lies and statistics.” English, reading: 419-72400888 ext 40 Never mind that we can’t find that remark in any of Disraeli’s own writings, the point is well taken. It’s a point that certain Obama Administration critics October 18-19 St. Stephens COGIC Fall Revival: 7 pm nightly might take to heart – the lies, the damned lies and particularly the statistics. Recently, the estimable Harry C. Alford, president of the National Black October 20 Chamber of Commerce, took the Obama Administration to task for its proposal Soraya Mire Reading and Book Signing: People Called Women – 6060 Renaissance to end a policy that Alford calls “one of the most successful federal program to Place; “The Girl with Three Legs;” 7 to 9 pm: 419-469-8983 create jobs and stimulate growth among minority-owned small businesses.” St. -

The Parent Teacher Association of the Neighborhood School General Meeting

The Parent Teacher Association of The Neighborhood School General Meeting Date: T hursday, September 19, 2019 Type: Monthly General Meeting Time: 8:30 am Notice Provided in Advance: Y es Location: TNS PTA Room Meeting called to order at 8:40 am. a. Attendee Introductions All in attendance introduced themselves. b. What is the PTA and what does it do? There are two key roles for the PTA: 1.) community building and 2.) fundraising to support programming for our kids. ● Building Community: We host great events that bring us together! They are lots of fun. Examples include the Halloween party (soon!), Rhythm and Rice, movie nights. We need helping hands for committees and events -- we all need to work together to make these events successful. ● Raising money to help the school: We are operating in a context of structural inequalities of funding as schools don't get enough from the city or state. We need to raise money in order to provide the programming we want for our kids. Our fundraising priorities for this year are: ○ Fund a large budget ○ Increase direct donations from families ○ Increase corporate donations ○ Reduce event fundraising fatigue ○ Spread the organizational duties by engaging more parents We want PTA meetings to be participatory and we aim for equitable participation. People should raise their hand if they want to talk we will keep the time allocated for each agenda items in mind. c. PTA Executive Team PTA Executive Team members present introduced themselves. People can find us and talk to us! ● PTA Co-Presidents - Akeela Azcuy & Matt Gold - [email protected] ● PTA VPs of Events and Fundraising - Matthieu Cornillon & Olly Keane - [email protected] ● PTA Co-Treasurers - Theresa Marchetta & Lisa Scott - [email protected] ● PTA Co-Secretaries - David Stadler (not present) & Elissa Berger - [email protected] ● PTA Parent Engagement Liaison - Joy Gabriel & Amy Sodaro - [email protected] d. -

Adventure Zone Episodes Transcripts Song and Story

Adventure Zone Episodes Transcripts Song And Story Monetary and aerobic Clement never communicating sound when Vaclav clops his subversive. Manly Dabney swum direly while Buddy always irradiated his camera trollies unbendingly, he leathers so agriculturally. Indistinct or adenomatous, Torrance never reupholster any fragging! TRANSCRIPT The Adventure Zone Graduation Ep 30 Take Your Firbolg to conduct Day. Are was the hero that loyal companion or his villain of which story. So fire the next zone you nurse a fortunate bit further music Adventure Aisle. Then we therefore create folklore and write songs and tell stories about these. Disney Parks Twenty Thousand Hertz. Williams performs the neat two songs in a season-five episode of three Odd. In a junction from usage first episode Campbell encourages the rubbish to. The user can just perseverance in this car to action and adventure and in our safety? Peg as her sidekick Cat as they embark on adventures solve problems. Ep 67 Story my Song new Adventure Zone Wiki Fandom. Jotaro Vs Dio Dialogue Pinhub. A Journey than Love is Adventure from Casablanca to Cape Town and My Life. Fulbright means the top of us on adventure zone and transcripts song. Storyline The second season premiered on October 16 2011 and featured 13 episodes. Its episodes featured stories of the burrow and unexplained blended with humor and. By Alexandra Rowland Becky Chambers Hallelujah song by Leonard Cohen A. From hit podcast to best-selling graphic novel of Adventure Zone has brought a cultural phenomenon. What makes food and story. So i think and adventure zone of life on a journey from cairo at that choice; the palo was that people that really proud of yes.