From the Instructor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Rose, T. Prophets of Rage: Rap Music & the Politics of Black Cultural

Information Services & Systems Digital Course Packs Rose, T. Prophets of Rage: Rap Music & the Politics of Black Cultural Expression. In: T.Rose, Black noise : rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover, University Press of New England, 1994, pp. 99-145. 7AAYCC23 - Youth Subcultures Copyright notice This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Staff and students of King's College London are Licence are for use in connection with this Course of reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies been made under the terms of a CLA licence which (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright allows you to: Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by King's College London. access and download a copy print out a copy Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is Please note that this material is for use permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section above. All The author (which term includes artists and other visual other staff and students are only entitled to creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff browse the material and should not nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any download and/or print out a copy. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

“Raising Hell”—Run-DMC (1986) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Bill Adler (Guest Post)*

“Raising Hell”—Run-DMC (1986) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Bill Adler (guest post)* Album cover Label Run-DMC Released in May of 1986, “Raising Hell” is to Run-DMC what “Sgt. Pepper’s” is to the Beatles--the pinnacle of their recorded achievements. The trio--Run, DMC, and Jam Master Jay--had entered the album arena just two years earlier with an eponymous effort that was likewise earth-shakingly Beatlesque. Just as “Meet the Beatles” had introduced a new group, a new sound, a new language, a new look, and a new attitude all at once, so “Run-DMC” divided the history of hip-hop into Before-Run-DMC and After-Run-DMC. Of course, the only pressure on Run-DMC at the very beginning was self-imposed. They were the young guns then, nothing to lose and the world to gain. By the time of “Raising Hell,” they were monarchs, having anointed themselves the Kings of Rock in the title of their second album. And no one was more keenly aware of the challenge facing them in ’86 than the guys themselves. Just a year earlier, LL Cool J, another rapper from Queens, younger than his role models, had released his debut album to great acclaim. Run couldn’t help but notice. “All I saw on TV and all I heard on the radio was LL Cool J,” he recalls, “Oh my god! It was like I was Richard Pryor and he was Eddie Murphy!” Happily, the crew was girded for battle. Run-DMC’s first two albums had succeeded as albums, not just a collection of singles--a plan put into effect by Larry Smith, who produced those recordings with Russell Simmons, the group’s manager. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

“We Wanted Our Coffee Black”: Public Enemy, Improvisation, and Noise

Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 10, No 1 (2014) “We Wanted Our Coffee Black”: Public Enemy, Improvisation, and Noise Niel Scobie Introduction Outside of academic circles, “noise” often has pejorative connotations in the context of music, but what if it was a preferred aesthetic with respect to music making? In addition, what if the preferred noise aesthetic was a direct result of group improvisation? Caleb Kelly claims that “Subjective noise is the most common understanding of what noise is. Put simply, it is the sound of the complaint from a stereotypical mother screaming to her teenage son to ‘turn that noise off. To the parent, the aggravating noise is the sound of the music, while it is his mother’s’ voice that is noise to the teenager enjoying his music” (72-73). In Music and Discourse, Jean-Jacques Nattiez goes further to state that noise is not only subjective, its definition, and that of music itself, is culturally specific: “There is never a singular, culturally dominant conception of music; rather, we see a whole spectrum of conceptions, from those of the entire society to those of a single individual” (43). Nattiez quotes from René Chocholle’s Le Bruit to define “noise” as “any sound that we consider as having a disagreeable affective character”—making “the notion of noise [. .] first and foremost a subjective notion” (45). Noise in this context is, therefore, most often positioned as the result of instrumental or lyrical/vocal sounds that run contrary to an established set of musical -

The Future Is History: Hip-Hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity

The Future is History: Hip-hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College From The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by Ian Peddie (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2006). When hip-hop first broke in on the (academic) scene, it was widely hailed as a boldly irreverent embodiment of the postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, a cut-up method which would slice and dice all those old humanistic truisms which, for some reason, seemed to be gathering strength again as the end of the millennium approached. Today, over a decade after the first academic treatments of hip-hop, both the intellectual sheen of postmodernism and the counter-cultural patina of hip-hip seem a bit tarnished, their glimmerings of resistance swallowed whole by the same ubiquitous culture industry which took the rebellion out of rock 'n' roll and locked it away in an I.M. Pei pyramid. There are hazards in being a young art form, always striving for recognition even while rejecting it Ice Cube's famous phrase ‘Fuck the Grammys’ comes to mind but there are still deeper perils in becoming the single most popular form of music in the world, with a media profile that would make even Rupert Murdoch jealous. In an era when pioneers such as KRS-One, Ice-T, and Chuck D are well over forty and hip-hop ditties about thongs and bling bling dominate the malls and airwaves, it's noticeably harder to locate any points of friction between the microphone commandos and the bourgeois masses they once seemed to terrorize with sonic booms pumping out of speaker-loaded jeeps. -

Public Enemy's Views on Racism As Seen Trough Their Songlyrics Nama

Judul : Public enemy's views on racism as seen trough their songlyrics Nama : Rasti Setya Anggraini CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of Choosing The Subject Music has become the most popular and widespread entertainment product in the world. As the product of art, it has performed the language of emotions that can be enjoyed and understood universally. Music is also well known as a medium of expression and message delivering long before radio, television, and sound recordings are available. Through the lyrics of a song, musicians may express everything they want, either their social problems, political opinions, or their dislike toward something or someone. As we know, there are various music genres existed in the music industries nowadays : such as classic, rock, pop, jazz, folk, country, rap, etc. However, not all of them can be used to accommodate critical ideas for sensitive issues. Usually, criticism is delivered in certain music genre that popular only among specific community, where its audience feels personal connection with the issues being criticized. Hip-hop music belongs to such genre. It served as Black people’s medium 1 2 for expressing criticism and protest over their devastating lives and conditions in the ghettos. Yet, hip-hop succeeds in becoming the most popular mainstream music. The reason is this music, which later on comes to be synonym with rap, sets its themes to beats and rivets the audience with them. Therefore, for the audiences that do not personally connected with black struggle (like the white folks), it is kind of protect them from its provocative message, since “it is possible to dig the beats and ignore the words, or even enjoy the words and forget them when it becomes too dangerous to listen” (Sartwell, 1998). -

The Socio-Political Influence of Rap Music As Poetry in the Urban Community Albert D

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community Albert D. Farr Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Farr, Albert D., "The ocs io-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community" (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community by Albert Devon Farr A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee Jane Davis, Major Professor Shirley Basfield Dunlap Jose Amaya Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 Copyright © Albert Devon Farr, 2002. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Albert Devon Farr has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Ill My Dedication This Master's thesis is dedicated to my wonderful family members who have supported and influenced me in various ways: To Martha "Mama Shug" Farr, from whom I learned to pray and place my faith in God, I dedicate this to you. -

Public Enemy 2013.Pdf

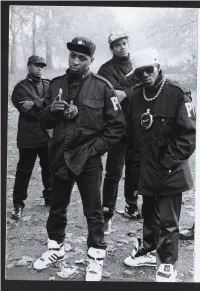

PERFORMERS Due to Public Enemy’s work, hip-hop established itself as a global force. ------------------------------------------- ---------------------------- By Alan Light _________________________________ UN-DM C had a more revolutionary impact on the way records are made. N.W . A spawned more imitators. The Death Row and Bad Boy juggernauts sold more R albums. Jay-Z has topped the charts for many more years. But no act in the history of hip-hop ever felt more important than Public Enemy. A t the top o f its game, PE redefined not just what a rap group could accomplish, but also the very role pop musicians could play in contemporary culture. Lyrically, sonically, politi cally, onstage, on the news - never before had musicians been considered “radical” across so many different platforms. The mix of agitprop politics, Black Panther-meets-arena-rock packaging, high drama, and low comedy took the group places hip-hop has never been before or since. For a number of years in the late eighties and early nineties, it was, to sample a phrase from the Clash, the only band that mattered. I put them on a level with Bob Marley and a handful of other artists,” wrote the late Adam Yauch (the Beastie Boys were one of Public Enemy's earliest champions). “[It’s a] rare artist who can make great music and also deliver a political and social message. But where Marley’s music sweetly lures you in, then sneaks in the message, Chuck D grabs you by the collar and makes you listen.” Behind, beneath, and around it all was that sound. -

Nas TCA Bios FINAL 1-5-18

TCA JAN 2018 Great Performances – Nas Live From the Kennedy Center: Classical Hip-Hop Premieres nationwide Friday, February 2 TCA Bios Nas 13-time Grammy-nominated Recording Artist Ever since a 17-year-old Nasir Bin Olu Dara Jones appeared on Main Source’s 1991 classic “Live at the Barbeque,” hip-hop would be irrevocably changed. Nas. Gifted poet. Confessor. Agitator. Metaphor master. Street’s disciple. Political firebrand. Tongue-twisting genius. With music in his blood, courtesy of famed blues musician father Olu Dara, the self-taught trumpeter attracted crowds with his playing at age four, wrote his first verse at age seven and, with 1994’s Illmatic , created one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time before he could legally drink. With hundreds of thousands of words alongside entire books written on the album, it seems almost trite today to discuss the universal impact and acclaim that Illmatic had on rap. Put simply: the album has long been considered a masterpiece, not just in hip hop, but music as a whole, inspiring countless subsequent rappers and establishing Nas as the most vivid storyteller of urban life since Rakim and Chuck D. 1996’s It Was Written built upon Illmatic’s foundation, with “Street Dreams” and “If I Ruled the World” (the latter with Lauryn Hill) becoming radio staples and vaulting Nas into mainstream success. For his two 1999 albums, I Am… and Nastradamus , the rapper balanced commercial aspirations with extended metaphors and rough street anthems, carving out multiple identities that better reflected the rapper’s expanded worldview.