Blitzstein's Musical Legacy Remarks Shared by Elizabeth Blaufox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Leonard Bernstein

chapter one Young American Bernstein at Harvard In 1982, at the age of sixty-four, Leonard Bernstein included in his col- lection of his writings, Findings, some essays from his younger days that prefi gured signifi cant elements of his later adult life and career. The fi rst, “Father’s Books,” written in 1935 when he was seventeen, is about his father and the Talmud. Throughout his life, Bernstein was ever mind- ful that he was a Jew; he composed music on Jewish themes and in later years referred to himself as a “rabbi,” a teacher with a penchant to pass on scholarly learning, wisdom, and lore to orchestral musicians.1 Moreover, Bernstein came to adopt an Old Testament prophetic voice for much of his music, including his fi rst symphony, Jeremiah, and his third, Kaddish. The second essay, “The Occult,” an assignment for a freshman composi- tion class at Harvard that he wrote in 1938 when he was twenty years old, was about meeting Dimitri Mitropoulos, who inspired him to take up conducting. The third, his senior thesis of April 1939, was a virtual man- ifesto calling for an organic, vernacular, rhythmically based, distinctly American music, a music that he later championed from the podium and realized in his compositions for the Broadway stage and operatic and concert halls.2 8 Copyrighted Material Seldes 1st pages.indd 8 9/15/2008 2:48:29 PM Young American / 9 EARLY YEARS: PROPHETIC VOICE Bernstein as an Old Testament prophet? Bernstein’s father, Sam, was born in 1892 in an ultraorthodox Jewish shtetl in Russia. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1917 www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu 1-800-FDR-VISIT October 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cliff Laube (845) 486-7745 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library Author Talk and Film: Susan Quinn Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times HYDE PARK, NY -- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is pleased to announce that Susan Quinn, author of Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, will speak at the Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center on Sunday, October 26 at 2:00 p.m. Following the talk, Ms. Quinn will be available to sign copies of her book. Furious Improvisation is a vivid portrait of the turbulent 1930s and the Roosevelt Administration as seen through the Federal Theater Project. Under the direction of Hallie Flanagan, formerly of the Vassar Experimental Theatre in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Federal Theater Project was a small but highly visible part of the vast New Deal program known as the Works Projects Administration. The Federal Theater Project provided jobs for thousands of unemployed theater workers, actors, writers, directors and designers nurturing many talents, including Orson Welles, John Houseman, Arthur Miller and Richard Wright. At the same time, it exposed a new audience of hundreds of thousands to live theatre for the first time, and invented a documentary theater form called the Living Newspaper. In 1939, the Federal Theater Project became one of the first targets of the newly-formed House Un-American Activities Committee, whose members used unreliable witnesses to demonstrate that it was infested with Communists. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

A Study of Music As an Integral Part

A Study of Music as an Integral Part of the Spoken Drama in the American Professional Theatre: 1930-1955 By MAY ELIZABETH BURTON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA August, 1956 PREFACE This is a study of why and how music is integrated with spoken drama in the contemporary American professional theatre. Very little has been written on the subject, so that knowledge of actual practices is limited to those people who are closely associated with commercial theatre-- composers, producers, playwrights, and musicians. There- fore, a summation and analysis of these practices will contribute to the existing body of knowledge about the contemporary American theatre. It is important that a study of the 1930-1955 period be made while it is still contemporary, since analysis at a later date would be hampered by a scarcity of detailed production records and the tendency not to copyright and publish theatre scores. Consequently, any accurate data about the status of music in our theatre must be gathered and re- corded while the people responsible for music integration are available for reference and correspondence. Historically, the period from 1930 to 1^55 is important because it has been marked by numerous fluc- tuations both in society and in the theatre. There are evidences of the theatre's ability to serve as a barometer of social and economic conditions. A comprehension of the ii degree and manner in which music has been a part of the theatre not only will provide a better understanding of the relationship between our specific theatre idiom and society, but suggests the degree to which it differs from that fostered by previous theatre cultures. -

An Educational Guide Filled with Youthful Bravado, Welles Is a Genius Who Is in Love with and Welles Began His Short-Lived Reign Over the World of Film

Welcome to StageDirect Continued from cover Woollcott and Thornton Wilder. He later became associated with StageDirect is dedicated to capturing top-quality live performance It’s now 1942 and the 27 year old Orson Welles is in Rio de Janeiro John Houseman, and together, they took New York theater by (primarily contemporary theater) on digital video. We know that there is on behalf of the State Department, making a goodwill film for the storm with their work for the Federal Theatre Project. In 1937 their tremendous work going on every day in small theaters all over the world. war effort. Still struggling to satisfy RKO with a final edit, Welles is production of The Cradle Will Rock led to controversy and they were This is entertainment that challenges, provokes, takes risks, explodes forced to entrust Ambersons to his editor, Robert Wise, and oversee fired. Soon after Houseman and Welles founded the Mercury Theater. conventions - because the actors, writers, and stage companies are not its completion from afar. The company soon made the leap from stage to radio. slaves to the Hollywood/Broadway formula machine. These productions It’s a hot, loud night in Rio as Orson Welles (actor: Marcus In 1938, the Mercury Theater’s War of the Worlds made appear for a few weeks, usually with little marketing, then they disappear. Wolland) settles in to relate to us his ‘memoir,’ summarizing the broadcast history when thousands of listeners mistakenly believed Unless you’re a real fanatic, you’ll miss even the top performances in your early years of his career in theater and radio. -

PUMP BOYS and DINETTES

PUMP BOYS and DINETTES to star Jordan Dean, Hunter Foster, Mamie Parris, Randy Redd, Katie Thompson, Lorenzo Wolff Directed by Lear deBessonet; Choreographed by Danny Mefford Free Pre-Show Events Include Original Casts of “Pump Boys” and [title of show] July 16 – July 19 2014 Encores! Off- Center Jeanine Tesori, Artistic Director; Chris Fenwick, Music Director New York, N.Y., May 27, 2014 - Pump Boys and Dinettes, the final production of the 2014 Encores! Off-Center series, will star Jordan Dean, Hunter Foster, Mamie Parris, Randy Redd, Katie Thompson and Lorenzo Wolff. Pump Boys, running July 16 – 19, will be directed by Lear deBessonet and choreographed by Danny Mefford. Jeanine Tesori is the Encores! Off-Center artistic director; Chris Fenwick is the music director. Pump Boys and Dinettes was conceived, written and performed by John Foley, Mark Hardwick, Debra Monk, Cass Morgan, John Schimmel and Jim Wann. The show is a musical tribute to life on the roadside, with the actors accompanying themselves on guitar, piano, bass, fiddle, accordion, and kitchen utensils. A hybrid of country, rock and pop music, Pump Boys is the story of four gas station attendants and two waitresses at a small-town dinette in North Carolina. It premiered Off-Broadway at the Chelsea West Side Arts Theatre in July 1981 and opened on Broadway on February 4, 1982 at the Princess Theatre, where it played 573 performances and was nominated for both Tony and Drama Desk Awards for Best Musical. THE ARTISTS Jordan Dean (Jackson) appeared on Broadway in Mamma Mia!, Cymbeline and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. -

The Second Instrumental Unit

Festival Concert IV Saturday June 7, 2008 4:00 pm The American Composers Alliance presents: The Second Instrumental Unit David Fulmer, Eliot Gattegno, Marc Dana Williams, Co-Directors, and New York Women Composers, Inc. With special guests: Christopher Oldfather, piano Benjamin Fingland, clarinet, Marilyn Nonken, piano Peter Clark, baritone, Michael Fennelly, piano FIVE LIVE CONCERTS MORE THAN 30 COMPOSERS Festival Schedule: Wednesday, June 4 at 7:30pm Leonard Nimoy Thalia Thursday, June 5 at 7:30pm at Peter Norton Symphony Space Friday, June 6 at 7:30pm 2537 Broadway at 95th St. Saturday, June 7 at 4:00pm New York City Saturday, June 7 at 7:30pm Complete festival schedule of works to be performed, and additional biographical information on the composers and performers, link at www.composers.com The American Composers Alliance is a not-for-profit corporation. This event is made possible in part, with funds from the Argosy Foundation, BMI, the City University Research Fund, the Alice M. Ditson Fund of Columbia University, NYU Arts and Sciences Department of Music, and other generous foundations, businesses, and individuals. 1 The Second Instrumental Unit David Fulmer, Eliot Gattegno, Marc Dana Williams, Co-Directors New York Women Composers, Inc. Marc Dana Williams, conductor All performers from the Second Instrumental Unit unless otherwise noted: Margarita Zelenaia Homage, Suite for Clarinet and Violin (2004) * Lisa Hogan Piece for Trumpet, Marimba, and String Quartet (2005) ‡ Eleanor Aversa Something Gleamed Like Electrum (2007) Margaret Fairlie-Kennedy Summer Solstice (2007) * Intermission Elizabeth Bell Night Music (1990) Christopher Oldfather, piano Beth Wiemann Erie, on the Periphery (2005)* Benjamin Fingland, clarinet Marilyn Nonken, piano Mark Blitzstein Cain (1930) * Peter Clark as “Jehovah” Michael Fennelly, piano *World premiere ‡ New York City premiere Summer Solstice, Erie, on the Periphery, CAIN, and Night Music are published or distributed by the American Composers Alliance. -

The Cradle Will Rock Program

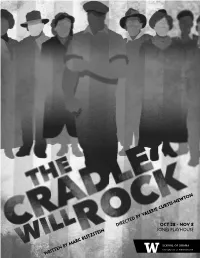

THE CRADLE WILL ROCK written by Marc blitzstein directed by valerie curtis-newton^° Scenic Design Lighting Design Musical Directors Technical Director Stage Manager Jennifer Zeyl^ Kyle Soble* Scott Hafso^° Alex Danilchik^ Robin Obourn José Gonzales Costume Design Sound Design Fawn Bartlett* Jacob Israel * Member of the Master of Fine Arts Program in Design ^Alumnus/Alumna of UW Drama °Faculty of UW Drama Prop Master Asst. Costume Designer Costume Crew Jake Lemberg Andrea Bush^ Monica Gonzalez Lindsey Crocker Becky Su Emma Halliday Lingjiao Wang Assistant Stage Managers Asst. Lighting Designer Hannah Knapp-Jenkins Megan Bernovich Amber Parker* Caitlin Manske Photographer Aaron Jin Lina Phan Mike Hipple Model Builder House Manager Montana Tippett Laundry Tickets Monica Gonzalez ArtsUW Ticket Office Light Board Operator Samantha de Jong Asst. Scenic Designer Jacqueline Wagner Running Crew Julia Welch^ Gabi Boettner Ross Jackson Yuchen Jin Mercedes Larkin Special Thanks: 5th Avenue Theatre, ACT Theatre, Jerry Chambers, Seattle Children's Theatre, Seattle Opera, Seattle Repertory Theatre, Theatre Puget Sound, UW Student Technology Fee, Village Theatre *member of the Professional Actor Training Program (PATP) CAST ^Alumnus/Alumna of UW Drama °Faculty of UW Drama John Houseman....................................... Andrew McMasters^ Editor Daily.............................................. AJ Friday* Orson Welles............................................ Andrew Russell Yasha........................................................ Hazel Lozano* -

“Preludes” a New Musical by Dave Malloy Inspired by the Music of Sergei Rachmaninoff Developed with and Directed by Rachel Chavkin

LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE EISA DAVIS, GABRIEL EBERT, NIKKI M. JAMES, JOSEPH KECKLER, CHRIS SARANDON, AND OR MATIAS, ON PIANO TO BE FEATURED IN THE LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “PRELUDES” A NEW MUSICAL BY DAVE MALLOY INSPIRED BY THE MUSIC OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF DEVELOPED WITH AND DIRECTED BY RACHEL CHAVKIN SATURDAY, MAY 23 THROUGH SUNDAY, JULY 19 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JUNE 15 AT THE CLAIRE TOW THEATER REHEARSALS BEGIN TODAY, APRIL 21 Eisa Davis, Gabriel Ebert, Nikki M. James, Joseph Keckler, Chris Sarandon, and Or Matias, on piano, begin rehearsals today for the LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater production of PRELUDES, a new musical by Dave Malloy, inspired by the music of Sergei Rachmaninoff, developed with and directed by Rachel Chavkin. PRELUDES, a world premiere and the first musical to be produced by LCT3 in the Claire Tow Theater, begins performances Saturday, May 23, opens Monday, June 15, and will run through Sunday, July 19 at the Claire Tow Theater (150 West 65th Street). From the creators of Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812, PRELUDES is a musical fantasia set in the hypnotized mind of Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. After the disastrous premiere of his first symphony, the young Rachmaninoff (to be played by Gabriel Ebert) suffers from writer’s block. He begins daily sessions with a therapeutic hypnotist (to be played by Eisa Davis), in an effort to overcome depression and return to composing. PRELUDES was commissioned by LCT3 with a grant from the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation. Paige Evans is Artistic Director/LCT3. -

Eric A. Gordon's Mark the Music: the Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein Collection, 1850-2011 Coll2012.121

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g161fq No online items Finding Aid to Eric A. Gordon's Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein Collection, 1850-2011 Coll2012.121 Finding aid prepared by Loni Shibuyama Processing this collection has been funded by a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California, 90007 (213) 741-0094 [email protected] (c) 2012 Coll2012.121 1 Title: Eric A. Gordon's Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein Collection Identifier/Call Number: Coll2012.121 Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Language of Material: English Physical Description: 6.0 linear feet.5 archives boxes + 1 archive binder box + 1 archive flat box. Date (bulk): Bulk, 1980-1991 Date (inclusive): 1850-2011 Abstract: Correspondence, playbills, programs, clippings, photographs, notes, grant proposals and other research material collected for the book, Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein (St. Martin's Press, 1989), by Eric A. Gordon. An American composer and gay man, Marc Blitzstein is perhaps most well-known for his 1937 musical, The Cradle Will Rock. The collection includes materials documenting Blitzstein's musical works, as well as correspondence files between biographer Eric A. Gordon and Blitzstein's family, friends and collaborators. creator: Gordon, Eric A., 1945- Biography on Marc Blitzstein Marc Blitzstein was born in Philadelphia, March 2, 1905. At the age of 6, he played his first solo piano recital in public; at 16, he performed a piano concert with the Philadelphia Symphony.