Cooperative Breeding Shapes Post‐Fledging Survival in An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tanzania, 30 November to 21 December 2020

Tanzania, 30 November to 21 December 2020 Thomas Pettersson This tour was organized by Tanzania Birding and Beyond Safaris and unfortunately, I was the only participant as my friend was prevented from going as was planned. The flights from Stockholm via Addis Ababa to Dar es Salaam and back with Ethiopian Airlines were uneventful. The only differences from my previous flights were that wearing face masks on the aircrafts was mandatory, and recommended at the airports, and that they checked my body temperature at both arrival and departure. I am not sure what the consequences would have been in case of fever. You must also complete a health declaration both for transfer and arrival. The outbound flight from Stockholm to Addis Ababa was about half empty and on the return perhaps only 25 % of the seats were occupied, which meant good nights sleep on three seats both ways. The flights between Addis Ababa and Dar es Salaam were fully booked both ways. The domestic flights with Coastal Aviation from Dar es Salaam via Zanzibar (Unguja) to Pemba and on to Tanga were also smooth, with the same regulations as above. The aircrafts were painfully small though, 12 seats. Not much space for legs and hand luggage. On the other hand, the distances are short. All in all, the tour was a big success. Accommodation was generally good, although basic at some places, but nothing to complain about. Food was excellent and plentiful, and I had no issues with the stomach. The drivers and the guides were excellent, in particular the outstanding Anthony, who guided most of the tour. -

Malawi Trip Report 2011

Malawi Trip Report 2011 Stanley Bustard (Denham's) in Nyika National Park 1(30) Malawi Trip Report, 30 October - 12 November 2011 A birdwatching tour perfectly arranged by Birding Africa (http://www.birdingafrica.com). Participants: Joakim, Elisabeth, Adrian (15) and Nova (10) Djerf from Östhammar, Sweden. Areas visited: Dzalanyama, Viphya Plateau, Nyika NP, Lake Malawi, Zomba and Liwonde NP. Total number of bird species recorded: 319 Total number of mammal species recorded: 23 Top 10 birds (our experience): 1. Pennant-winged Nightjar 2. Stanley Bustard (Denham's) 3. Cholo Alethe 4. Bar-tailed Trogon 5. White-winged Apalis 6. Anchieta's Sunbird 7. Livingstone's Flycatcher 8. Thick-billed Cuckoo 9. Boehm's Bee-eater 10. White-starred Robin Important literature and sound recordings: ✓ Southern African Birdfinder (Callan Cohen, Claire Spottiswoode, Jonathan Rossouw) ✓ The Birds of Malawi (Francoise Dowsett-Lemaire, Robert J. Dowsett) ✓ Birds of Africa south of the Sahara (Ian Sinclair, Peter Ryan) ✓ Bradt Guide: Malawi (Philip Briggs) ✓ The Kingdon pocket guide to African Mammals (Jonathan Kingdon) ✓ Sounds of Zambian Wildlife (Robert Stjernstedt) General about the trip: This was, with two exceptions (Zomba and Liwonde), a self catering trip. Self catering in Malawi means you bring your own food to the accommodation but get it prepared by the always present local cook and (often) his one or two assistants. This worked perfectly well in every place we stayed. All meals were thoroughly prepared and tasted very good. None of us had any stomach problems at all in the whole trip and we ate everything we was served. We do recommend this arrangement when travelling in Malawi. -

Ultimate Kenya

A pair of fantastic Sokoke Scops Owls. (DLV). All photos taken by DLV during the tour. ULTIMATE KENYA 1 – 20 / 25 APRIL 2017 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO Kenya lived up to its reputation of being one of the most diverse birding destinations on our planet. Once again, our Ultimate Kenya recorded a mind-boggling total of more than 750 species. This was despite the fact that we were prioritizing Kenyan specialities (a task in which we were extremely successful) rather than going all out for a huge list! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Kenya www.birdquest-tours.com The first leg of our epic adventure saw us focusing on the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest where the birding is tough but the rewards are great. Over the course of the two and a half days our talented local guide helped us find all of the main specialities, with the exception of the difficult Clarke’s Weavers, which were presumably on their recently discovered breeding grounds in marshes to the north. Crested Guineafowl and Northern Carmine Bee-eater. We spent much time creeping along sandy tracks, gradually finding our targets one by one. We succeeded in getting great views of a number of skulkers, including a rather showy East Coast Akalat on our last afternoon, some reclusive Eastern Bearded Scrub Robins, a very obliging Red-tailed Ant Thrush and skulking Fischer’s and Tiny Greenbuls. Once in the Brachystegia we kept our eyes and ears open for roving flocks of flock-leader Retz’s and Chestnut-fronted Helmet Shrikes, and with these we found awkward Mombasa Woodpeckers and a single Green-backed Woodpecker, and a variety of smaller species including Black-headed Apalis, Green Barbet, Eastern Green Tinkerbird, dainty Little Yellow Flycatchers, Forest Batis, Pale Batis, cracking little Amani and Plain-backed Sunbirds and Dark-backed Weaver. -

Zambia and Malawi Trip Report – August/September 2014

Zambia and Malawi Trip Report – August/September 2014 Miombo Tit www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Zambia and Malawi August/September 2014 This trip was run as a customized tour for three clients, all with lists of well over 7000 species seen worldwide, and in fact Dollyann was hoping to reach 8000 species by the end of this trip. Travel to some really remote destinations, particularly in Malawi, was necessary to find some of the group’s target birds. Places like Misuku Hills and Uzumara Forest in Malawi are hardly ever visited by birders, primarily from a logistics point of view, and also because of lack of suitable accommodation. Both these destinations are, however, excellent birding spots, and Uzumara in particular could be included in most itineraries, using accommodation in the town of Rumphi as a base. On the Zambian side we included the Mwinilunga area, a must for any serious birder; this area hosts many Angolan/Congo specials, found nowhere else in Zambia. Day 1, 14th August. Livingstone Airport to Lodge Ron, Dollyann, and Kay arrived on the same flight from Johannesburg at around 13h00. After a short meet and greet and a quick visit to the bank for some local currency, we loaded up and started our journey to our lodge. Not much was seen en route other than a few marauding Pied Crows and a single African Grey Hornbill. We arrived at the lodge in good time and decided to take 20 minutes to refresh, before starting our bird quest. -

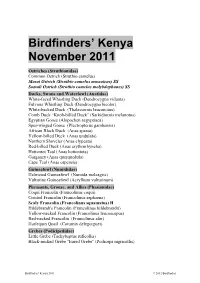

2011 Species List

Birdfinders’ Kenya November 2011 Ostriches (Struthionidae) Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus) Masai Ostrich (Struthio camelus massaicus) SS Somali Ostrich (Struthio camelus molybdophanes) SS Ducks, Swans and Waterfowl (Anatidae) White-faced Whistling Duck (Dendrocygna viduata) Fulvous Whistling Duck (Dendrocygna bicolor) White-backed Duck (Thalassornis leuconotus) Comb Duck “Knob-billed Duck” (Sarkidiornis melanotos) Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca) Spur-winged Goose (Plectropterus gambensis) African Black Duck (Anas sparsa) Yellow-billed Duck (Anas undulata) Northern Shoveler (Anas clypeata) Red-billed Duck (Anas erythrorhyncha) Hottentot Teal (Anas hottentota) Garganey (Anas querquedula) Cape Teal (Anas capensis) Guineafowl (Numididae) Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris) Vulturine Guineafowl (Acryllium vulturinum) Pheasants, Grouse, and Allies (Phasianidae) Coqui Francolin (Francolinus coqui) Crested Francolin (Francolinus sephaena) Scaly Francolin (Francolinus squamatus) H Hildebrandt's Francolin (Francolinus hildebrandti) Yellow-necked Francolin (Francolinus leucoscepus) Red-necked Francolin (Francolinus afer) Harlequin Quail (Coturnix delegorguei) Grebes (Podicipedidae) Little Grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis) Black-necked Grebe “Eared Grebe” (Podiceps nigricollis) Birdfinders' Kenya 2011 © 2012 Birdfinders Flamingos (Phoenicopteridae) Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) Lesser Flamingo (Phoenicopterus minor) Storks (Ciconiidae) Black Stork (Ciconia nigra) Eurasian White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) Saddle-billed Stork (Ephippiorhynchus -

Fission-Fusion Dynamics in the Facultative Cooperative Breeding Placid Greenbul (Phyllastrephus Placidus)

Biology Department Research Group Terrestrial Ecology Unit (TEREC) _____________________________________________________________________________________ FISSION-FUSION DYNAMICS IN THE FACULTATIVE COOPERATIVE BREEDING PLACID GREENBUL (PHYLLASTREPHUS PLACIDUS) Rori Sys Studentnumber: 01302591 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Luc Lens Scientific tutor: MSc Laurence Cousseau Master’s dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of Master of Science in Biology Academic year: 2018 - 2019 Introduction Fission-fusion dynamics within social species are a relatively well observed phenomenon (Silk et al.; 2014 (1)). Fission includes behaviours where groups either split up in subgroups or just completely dissipate. Fusion behaviour on the other hand is characterized by the forming of new groups or the growth of a group. Cooperative breeding is a type of breeding-behaviour where more than two individuals provide care at a single nest. In a recent study it was observed that at least 9% of all passerines show this behaviour (Leedale et al.; 2018 (2)). Numerous hypotheses try to explain the origin of this behaviour, including the ‘inclusive fitness hypothesis’ (cf. infra). The role of the environment is also still under debate. We will be looking at this type of behaviour through the lens of fission-fusion dynamics. The breeding pair is the centre of any cooperative breeding group. Changes to it will affect the entire group significantly. Fission-fusion behaviour surrounding the breeding pair encompass the forming of the pair and their reasons for staying together or breaking up. Pairs can stay together for multiple breeding seasons, sometimes even for entire lifetimes, like in the case of the bearded reedling (Griggio and Hoi ;2011 (3)). However, it is not always clear what the main benefits are of choosing to stay together. -

The Avifauna, Conservation and Biogeography of the Njesi Highlands in Northern Mozambique, with a Review of the Country's Afro

Ostrich Journal of African Ornithology ISSN: 0030-6525 (Print) 1727-947X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tost20 The avifauna, conservation and biogeography of the Njesi Highlands in northern Mozambique, with a review of the country’s Afromontane birdlife Samuel EI Jones, Gabriel A Jamie, Emidio Sumbane & Merlijn Jocque To cite this article: Samuel EI Jones, Gabriel A Jamie, Emidio Sumbane & Merlijn Jocque (2020) The avifauna, conservation and biogeography of the Njesi Highlands in northern Mozambique, with a review of the country’s Afromontane birdlife, Ostrich, 91:1, 45-56, DOI: 10.2989/00306525.2019.1675795 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2019.1675795 View supplementary material Published online: 17 Mar 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tost20 Ostrich 2020, 91(1): 45–56 Copyright © NISC (Pty) Ltd Printed in South Africa — All rights reserved OSTRICH ISSN 0030–6525 EISSN 1727-947X https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2019.1675795 The avifauna, conservation and biogeography of the Njesi Highlands in northern Mozambique, with a review of the country’s Afromontane birdlife Samuel EI Jones1,2,3*+ , Gabriel A Jamie3,4,5+ , Emidio Sumbane3,6 and Merlijn Jocque3,7 1 School of Biological Sciences, University of London, Egham, United Kingdom 2 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United -

Preliminary Observations on the Avifauna of Ikokoto Forest, Udzungwa Mountains, Tanzania

Scopus 32: 19–26, June 2013 Preliminary observations on the avifauna of Ikokoto Forest, Udzungwa Mountains, Tanzania Chacha Werema, Jay P. McEntee, Elia Mulungu and Maneno Mbilinyi Summary A study was conducted at c. 110 ha of Ikokoto forest using mist-netting and general field observations. Sixty-four species were recorded of which 61% were of conservation importance in terms of forest dependence. All species were found to belong to the familiar assembly of the large Udzungwa forests. Six species, the Green-throated Greenbul Andropadus fusciceps, Spot-throat Modulatrix stictigula, African Tailorbird Artisornis metopias, Black-lored Cisticola Cisticola nigriloris, Uhehe Fiscal Laniarius marwitzi and Fülleborn’s Black Boubou Laniarius fuelleborni detected are restricted range and one species Moreau’s Sunbird Nectarinia moreaui is near- threatened according to IUCN threat status. The presence of many species which are forest dependent in this tiny forest indicates that this site, though small in size and highly fragmented, retains significant conservation value for birds. Introduction Ikokoto Forest lies in the northeast part of the Udzungwa Mountains, southern Tanzania. The latter form the southernmost and largest block of the Eastern Arc Mountains, which are known globally for extraordinarily high levels of endemism, largely attributed to their ancient geological age and long-term climatic stability (Lovett & Wasser 1993). Like many other Eastern Arc Mountain forests, Ikokoto forest is fragmented; it covers the peaks of two hills, which are surrounded by farmland matrix and isolated from other forest patches. Both fragments are under pressure from hunting, agriculturalist conversion, timber felling, and extraction of other wood products such as building poles and fuel wood. -

Birdwatching Uganda Including Elgon and Kidepo Dec-Jan 2018/19 by Theis Bacher Nielsen and Anders Bacher Nielsen

Shoebill, Mabamba Swamps Birdwatching Uganda including Elgon and Kidepo Dec-Jan 2018/19 By Theis Bacher Nielsen and Anders Bacher Nielsen This report summarizes a trip made over Christmas and New Year 2018/2019. After evaluating several options, we decided to plan the trip ourselves but with local assistance. We had a guide and an 4WD the entire trip and we decided to include locations not regularly visited by birders, namely Elgon National Park and Kidepo National Park. Kidepo NP added 90 bird species only seen there while Elgon NP added another 26 species only seen there. Many of these birds can of course be seen elsewhere in Uganda (and we did not look actively for them after first sighting) but especially Kidepo NP is highly recommended. The “detour” from Lira is manageable and the birding, the scenery and the lodges there are fantastic. Also, try to get the local ranger/guide Zakari, he is fantastic. As a bonus we encountered a Giant Pangolin during an evening drive. We saw a total number of 620 species. The itinerary Date Route – Activity Hotel National Park/activity payments per person 23rd Dec Birding Entebbe Botanical Garden Precious Guesthouse 10,000UGX 24th Dec Mabamba Swamps → Mabira Griffin Falls Camp Minor entrance fee and a boat/guide fee Forest 25th Dec Mabira Forest The Rainforest Lodge 20,000UGX entrance, 80,000UGX activity 26th Dec Mabira → Elgon Sipi River Lodge None 27th Dec Elgon → Lira Gracious Palace Hotel 35US$ entrance, 30US$ activity 28th Dec Lira → Kidepo Kidepo Savanna Lodge None 29th Dec Kidepo Kidepo Savanna -

Remote Tanzania

The Rufous-winged Sunbird was discovered in the Udzungwa Mountains in 1981 and its population is estimated at 6,850 individuals. We enjoyed exceptionally good views this year of this most unusually coloured sunbird. (Nik Borrow) REMOTE TANZANIA 3 – 25 OCTOBER 2014 LEADER: NIK BORROW We had first visited the more remote mountains of the Eastern Arc Mountains in 2003 and since then we have evolved and reformatted this specialist tour that embraces spiky East African thorn-bush, dry scrubby plains and floodplains, miombo woodland and of course those havens of biodiversity and endemism; the Eastern Arc Mountains and remote Pemba Island. The aim of this trip was to try to see some of the most difficult endemic Tanzanian birds. We began with White-headed Mousebirds and Tsavo Sunbirds in the thorn-scrub en route to Same and brightly plumaged Taveta Golden Weavers along the Pangani River. On the heights of the South Pare Mountains, we sought out the South Pare White-eye and Usambara Double- collared Sunbird, Golden-winged Sunbird and Brown-breasted Barbet were also found. In the West Usambaras undergrowth skulkers such as Red-capped Forest Warbler, Spot-throat, White-chested Alethe 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Remote Tanzania www.birdquest-tours.com and Usambara Akalat (or Ground Robin) were all seen along with the recently split Usambara Thrush whilst the elusive Usambara Weaver was watched gleaning, nuthatch-like along the moss-festooned branches. The neighbouring East Usambara Mountains yielded Long-billed Forest Warbler, Kretschmer’s Longbill, Usambara Hyliota and Uluguru Violet-backed, Amani and Banded Green Sunbirds. -

EOU2019 Abstracts

Programme and Abstracts Edited by Erik Matthysen, Péter L. Pap, Gábor M. Bóné 12th European Ornithologists’ Union Congress 26 – 30 August 2019 Cluj Napoca Romania ORGANIZERS: SPONSORS /EXHIBITORS: https://conference.eounion.org/2019/ Copyright © 2019 European Ornithologists’ Union PUBLISHED BY THE SCIENCTIFIC PROGRAMME COMMITTEE AND THE LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (the “License”). You may not use this file except in compliance with the License. You may obtain a copy of the License at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0. Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software distributed under the License is distributed on an “AS IS” BASIS, WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied. See the License for the specific language governing permissions and limitations under the License. The design of this booklet is based on the Legrand Orange Book LATEX Template by Mathias Legrand (HTTP://WWW.LATEXTEMPLATES.COM) and was conceptualized by Zoltán Barta. Photograph credits: Attila Nagy, Ferenc Kósa, Péter L. Pap, Sebastian Bugariu, Konrád Zelina Conference logo is designed by Elemér Könczey APART FROM CORRECTING FOR OBVIOUS TYPOS, THE ABSTRACTS ARE PUBLISHED AS THEY WERE SUBMITTED BY THEIR AUTHORS. A Web based version of this booklet can be found at http://conference.eounion.org/wp-content/uploads/EOU2019_abstracts.pdf First printing, August 2019 Contents I General information 1 Welcome messages .....................................................6 1.1 Message from the EOU President6 1.2 Message from local organizers6 2 Organisers ..............................................................8 2.1 Local Organising Committee8 2.2 Scientific Programme Committee8 3 Related events ..........................................................9 II Programme 4 Monday, 26th August, 2019 ............................................. -

Tanzania, 2015

BIRDS, MAMMALS, AMPHIBIANS and REPTILES seen in Tanzania nov 4 – Nov 23 2015 Stefan Lithner African dwarf bittern CONTENT Introduction p 1 Itinerary in short p 2 Map p 2 Full Itinerary p 3 Checklist BIRDS p 24 Checklist: with comments: MAMMALS, p 45 Checklist with comments: TORTOISES and TERRAPINS p 57 Checklist: SNAKE p 58 Checklist with comments: LIZARDS p 58 Checklist with comments: FROGS p 60 Checklist with comments: BUTTERFLIES p 61 Checklist with comments DRAGFONFLIES p 62 Adresses and links p 62 1(62) Introduction A friend of mine encouraged me to consider an eco-trip to Tanzania for nature-studies. I was also introduced to a professional guide; James Alan Woolstencroft (James) in Arusha in north-eastern Tanzania. James is primarily a bird-guide, but with considerable knowledge about lots of other groups of animals and plants as well. Since I wished to study birds as well as mammals and what else we were going to come across, we started planning. Because Tanzania is not one of the very cheapest countries to tourist in, we agreed that James should try to arrange a budget trip. In May 2015 we felt we had arrived at an attractive itinerary. James arranged a driver Mr Stanley Bupanga Mbogo (Stanley) with his car, a 1994 Toyota Landcruiser, short version with a pop-up roof. Stanley then made most of the reservations for the nights. Tanzania is a quite East African country. The accommodations were to our satisfaction. A few times they were however quite “East African countryside-standard”. The arrangements were nevertheless charming, and also offering me a closer contact with the country.