To Mid-Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

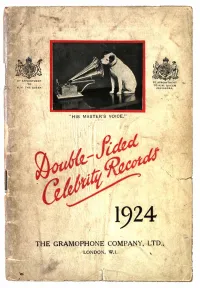

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

La Traviata GIUSEPPE VERDI Temporada 2020-2021

La traviata GIUSEPPE VERDI Temporada 2020-2021 Temporada Con la colaboración de: 1 La traviata - Giuseppe Verdi Patronato de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comisión ejecutiva de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Presidente de honor Presidente President de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Presidente del patronato Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Àngels Ponsa Roca, Lluís Baulenas Cases Vicepresidenta primera Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Àngels Ponsa Roca Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresidente segundo Vocales representantes del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona Andrea Gavela Llopis Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresidente tercero Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta cuarta Vocales representantes de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocales representantes del Consejo de Mecenazgo Lluis Baulenas Cases, Irene Rigau Oliver, Angels Barbara Fondevila Luis Herrero Borque, Elisa Durán Montolío Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Secretario Javier García Fernández, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Joan Francesc Joaquim Badia Armengol Marco Conchillo, Santiago de Torres Sanahuja Director general Vocales representantes del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona Valentí Oviedo Cornejo Marta Clari Padrós, Josep Maria Vallès Casadevall -

Cronologia Dels 175 Anys Del Liceu

anys del Liceu Junts seguirem fent història Cronologia dels 175 anys del Liceu 1837 Constitució de la Sociedad Dramática de Aficionados (24 febrer), a l’antic convent de Montsió i destinada al conreu de les arts. Es considera el nucli institucional del futur Liceu. El 14 de novembre s’aprova el primer reglament del Liceo Filodramático de Montesión, una societat per al desenvolupament de l’art dramàtic i el musical, l’origen del Conservatori del Liceu. Primera representació al convent de Montsió: El marido de mi mujer de Ventura de la Vega (21 agost). 1838 Primera representació d’una òpera al Convent de Montsió: Norma de Bellini (3 febrer). Reial Decret on s’autoritza el canvi de nom pel de Liceo Filarmónico Dramático Barcelonés de S. M. La Reina Isabel II (25 juny), amb la finalitat de promoure l’ensenyament teatral i musical i la de dur a terme representacions escèniques de teatre i òpera. 1841 Primeres documentacions per a la recerca d’un nou espai per a les activitats del Liceu. 1844 Adquisició i enderrocament de l’antic convent de Trinitaris (9 juny) a la Rambla, cantonada del carrer de Sant Pau. Oferta d’accions del futur teatre i aprovació del reglament (25 juliol), configurant la propietat privada del Liceu. anys del Liceu Junts seguirem fent història 1845 S’inicien les obres del Gran Teatre del Liceu (11 abril), per Miquel Garriga i Roca i Josep Oriol Mestres. El model fou l’arquitectura del Teatro allà Scala de Milà. 1847 Inauguració del Gran Teatre del Liceu (4 abril) que durant molts anys serà considerat el teatre d’òpera amb més capacitat d’Europa (més de tres mil persones). -

La Favorite (2017-2018).Pdf

TEMPORADA 2017-2018 TOURBILLON EXTRA-PLAT 5377 HISTORY IS STILL BEING WRITTEN... LA FAVORITE NAPOLÉON BONAPARTE (1769-1821) GAETANO DONIZETTI CLIENTE CÉLEBRE DE BREGUET – WWW.BREGUET.COM NAP_5377-Favorite_150x210.indd 1 21.09.17 11:04 Gracias por transmitirnos Hay un lugar para los vuestra energía durante que saben divertirse. estos 20 años. Si quieres emocionarte con los mejores eventos culturales, conocer a los personajes que admiras y experimentar con el arte en familia... Este es tu sitio. Solo pasa aquí, movistarlikes.es Movistar Likes Te gusta. Te apuntas. Lo vives. Foto: Magali Dougados Fotógrafo: Javier del Real endesa.com Página_15x21+3_S&S_Endesa2017_BAILARINA_TR_P_M_ES_v6.indd 1 17/10/17 17:03 MÁS DE HOY MÁS DE TODOS MÁS TEATRO REAL 1 PATROCINADORES DEL BICENTENARIO MECENAS PRINCIPAL MECENAS ENERGÉTICO TEMPORADA 2017-2018 PATROCINADORES DEL BICENTENARIO LA FAVORITE GAETANO DONIZETTI (1797-1848) Ópera en cuatro actos Libreto de Alphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz y Eugène Scribe Estrenada en la Opéra de Paris el 2 de diciembre de 1840 Estrenada en el Teatro Real el 19 de noviembre de 1850 GALA CONMEMORATIVA de la reapertura del Teatro Real el 11 de octubre de 1997 Ópera en versión de concierto 2, 6 de noviembre ADMINISTRACIONES PÚBLICAS ADMINISTRACIÓN PÚBLICA FUNDADORAS COLABORADORA 3 «Maldigo esta alianza, maldigo la indigna ofensa que sobre mí vuestra locura ha lanzado junto con el oro. ¡Rey! Guardemos, vos, el poder; yo, el honor, mi único tesoro.» FERNAND. LA FAVORITE (ACTO III, ESCENA XII) ALPHONSE ROYER, GUSTAVE VAËZ Y EUGÈNE -

Quick Reference List of VICTOR and BLUEBIRD RECORDS

Quick Reference List of VICTOR and BLUEBIRD RECORDS This list in conjunction with the Victor and Bluebird Catalogues contains all Victor and Bluebird records released up to and including June, mi (For records released during ensuing months, see monthly supplements) Quick Reference Booklet of Victor and Bluebird Records INDEX AND INFORMATION ON METHOD OF LISTING All records in this Quick Reference Booklet are conveniently listed by Title and Artist in alphabetical order in two separate sections. They are as follows: Victor Red Seal and Black Label Section, page 3 Bluebird Records, page 25 Thus, in seeking a particular selection, should you know either the Title or the Artist, the record can be quickly located by looking under the correct alphabetical category in the proper section. Musical Masterpiece Albums are listed alphabetically in a separate section beginning on page 13. Vocal Masterpiece Albums by Famous Artists are listed alphabetically in a separate section beginning on page 14. Victor Musical Smart Set Albums are listed alphabetically in a separate section beginning on page 15. Victor and Bluebird Records from Current Musical Shows and Motion Pictures are listed alphabetically in a separate section beginning on page 32. Victor and Bluebird French Records are listed alphabetically in a separate section on page 31. Victor and Bluebird Records Schedule of List Prices Red Seal Records Each Black Label Records Each 2100's & 2200's Ifl-inr.h $1.00 27000's 10-inch $ .75 4549*1 10-inch 1.00 36000's ...12-inch 1.00 13000's . 12-inch 1.35 120000's 10-inch .75 12-inch 1.35 130000's 12-inch 1.00 10-inch 1.00 216000's 10-inch .75 11-8100's 12-inch 1.35 V-700's & V-800's ...10-inch .75 Bluebird Records Each B-1200's 10-inch $ .50 B-4600's & B-4700's 10-inch .50 B-8700's 10-inch .50 B-8800's & B-8900's 10-inch .50 B-11000's 10-inch .50 V.R.—Denotes Vocal Refrain. -

Lev Sibiryakov

NI 7914 From Sibiryakov’s French repertoire there are three selections - from Lakmé, Faust and La Juive - demonstrating a good understanding of the style, exploiting his excellent vocal line, in fact showing the voice in all its glory. Sibiryakov’s initial training with Rossi in Milan must have left the strong impressions for he does not disappoint in his singing of Italian arias. Mephistophelean indeed is the tone he musters in the famous ‘Ave Signor’ from Boito’s Mefistofele, and in ‘Pro Pecatis’ from Rossini’s Stabat Mater, (the only item sung other than in Russian), he evinces an impressive nobility of utterance. ‘In felice’ from Verdi’s Ernani combines gravitas with a perfect legato - note the fluent florid LEV SIBIRYAKOV descending cadenza at the end - whilst in Colline’s ‘Farwell to his coat’ from the last act of Puccini’s La Bohème, Sibiriyakov does sound genuinely sad and self-sacrificing. In the selections from Wagner’s Lohengrin and Die Walküre it is the unforced volume of voice rising effortlessly above the orchestra that impresses, as do the majestic low F’s in the Lohengrin aria. Massenet’s Elegie gets a respectable reading, albeit a little fast for modern taste, but the simple melodic Russian songs by Gaiser, Romberg and Glazanov (especially the Tobolsk Convict song) seem to convey a more genuine emotion, as does his suitably dramatic performance of Field Marshall Death from Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death. Lev Sibiryakov may have stood in the shadow of his great contemporary, Fedor Chaliapin, for the greater part of a century, but this compilation reveals him as one of the greatest operatic voices ever to have been recorded. -

Milton Cross Born in Manhattan on 16 April 1897, Milton Cross Was One of Radio’S First Full- Time Announcers, and Remained So Until His Death on 3 January 1975

1 Milton Cross Born in Manhattan on 16 April 1897, Milton Cross was one of radio’s first full- time announcers, and remained so until his death on 3 January 1975. His association with the Saturday afternoon radio broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera’s matinee performances began literally with the first such broadcast: a performance of Hänsel and Gretel that aired on Christmas afternoon, December 25, 1931. Although Christmas Day fell on a Friday that year, the National Broadcasting Company decided to continue broadcasting Metropolitan Opera performances over its Blue Network (which later became the American Broadcasting Company, the corporate name of the ABC network) every Saturday afternoon, a holiday from work for most American men and women. In addition to his 43 consecutive seasons as radio’s Voice of the Metropolitan Opera,” Milton Cross served as an announcer for a variety of other radio programs including “The Magic Key of RCA” (a music program sponsored by RCA Victor), “Information Please” (an early quiz show), “Coast to Coast on a Bus” (a children’s show featuring child performers), and “The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street” (a highly popular jazz-and-blues program). He also narrated a number of film shorts (five- to fifteen-minute sound films that were shown between feature films in movie theaters), as well as educational and entertainment recordings for children, including “Peter and the Wolf” (Musicraft Records, 1949) and “The Magic of Music” (Cabot Records, 1964). Were either of your parents, or any of your siblings, involved in music? Not professionally, no. My father, Robert Cross, and my mother, Margret, who was called “Maggie” within the family, had six children, and I was the fifth of their brood of six. -

19.1 Historic Masters, Pp 220-228

HISTORIC MASTERS VINYL PRESSINGS MADE FROM THE ORIGINAL METALS Continuing in the tradition of IRCC and HRS, Historic Masters has made available to collectors limited editions of a host of historic recordings pressed on vinyl from stampers taken from the original EMI masters . Many of the records HM has issued are first and only editions, while others are extremely scarce in original form. Details as how to contact Historic Masters to purchase their latest issues will be found near the beginning of this catalogue in the Collectors’ Mart section . Offered below are issues from 1 to 214 (final single issue thusfar). The minimum bid is a uniform (remarkably low, I’d say) $6.00 each. All are as new, so I’ve not otherwise included grading or minimum bid information. Those described as unpublished are first and only 78 rpm editions. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6001. 10” HMA 1. CONCHITA SUPERVIA [ms]. LULLABY (Scott)/WHEN I BRING YOU COLOUR’D TOYS (Carpenter). 1932 London matrices. Both side unpublished . 6002. 10” HMA 2. FERNANDO DE LUCIA [t]. SERENAMENTE (Barthèlemy)/A SURRIENTA (de Curtis). From 1909 Gramophone matrices. 6003. 10” HMA 3. HINA SPANI [s]. CANCIÓN DEL CARRETERO (Buchardo)/DIA DEL FESTE (Ugarte). 1930 Italian Gramophone matrices. 6004. 10” HMA 4. FRANCESCO TAMAGNO [t]. TROVATORE: Di quella pira/OTELLO: Ora e per sempre addio (both Verdi). 1903 G&T matrices (3012ft/3025ft). Both unpublished takes . 6005. 12” HMB 5. MATTIA BATTISTINI [b] and ELVIRA BARBIERI [s]. TROVATORE: Mira d’acerbe/TROVATORE: Vivrà! Contende (Verdi). From 1913 Gram. matrices. 6006. 12” HMB 6. SELMA KURZ [s]. ERNANI: Involami/TROVATORE: D’amor sull’ ali rosee (both Verdi). -

ARSC Journal

THE YALE COLLECTION OF HISTORICAL SOUND RECORDINGS by Karol Berger Since about the turn of the century newly invented methods of sound recording began to be used regularly to document the activities of performing artists in many fields. In the last eighty years or so many ex amples of musical and theatrical performances, and also of literary readings and political oratory, have been preserved through the medium of recorded sound. The academic world's recognition of the educational and scholarly value of this material has been slow, and even today it is by no means universal. Yale University was one of the first institutions of higher learning and research in this country to per ceive this value and, as· the result of this percep tion, the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Record ings (HSR for short) was established as a part of the University Library in 1961. The Collection's purpose, which was formulated at its inception and which continues to guide its activities, is to collect, preserve, and make avail able for study sound recordings in the fields of the Western classical music and theater, poetry and literature, history and politics. It was decided initially not to collect jazz, popular, folk, or non Western music, because the University did not offer courses in these fields and also because they were represented in fine archives already in existence. Recently however, the Collection has accepted gifts of jazz and ethnographic records, since courses are now offered at Yale which may use such material. The man to whom HSR mostly owes its conception and continuing existence is Laurence C. -

02 – Spinning the Record

I: THE EARLY YEARS What on earth were they fighting over? To read the early history of recording, you would think that these people were arguing over shares of Microsoft stock or territory in the Middle East. These pioneers, some of whom really did have good intentions, were soon caught up in imbroglios, lawsuits and just plain nasty arguments that could make your head spin. It’s also rather hard to disentangle the vari- ous threads nowadays because, like all real history, none of it happened in a neat, linear fash- ion, but all jumbled together, lines drawn in the sand spilling all over each other as the tides of music fashions and different musical agendas rushed in from an ocean of public consumers. Reduced to essentials, it all seems so neat: Thomas Edison invents first practical phono- graph in 1877, sets it aside for 12 years and doesn’t bother to market or develop it as he turns his attentions to other matters (specifically electric light); other inventors pick up the thread around 1889, ten years later the flat disc begins to make significant inroads on the cylinder, by 1913 Edison throws in the towel and starts making flat discs of his own, in 1925 electrical re- cording replaces the old acoustical method, by which time radio is making significant inroads on the record industry itself. By 1930, thanks to the overwhelming popularity of radio and the Depression, the record industry is floundering; new techniques and marketing ideas help keep it afloat through the Depression and War years, then it blossoms in a Renaissance of long-play albums, stereo sound and a seemingly unlimited market.