USA General Election Final Report 3Rd November 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum 1 WC-21-01

CITY OF ALBANY Public Works Department ADDENDUM #1 WC-21-01, 40th Avenue Canal Bank Repair In order to clarify the intent of the Specifications and Drawings, the following provisions are provided and shall be considered part of the contract documents. CONTRACT DOCUMENTS Appendix A Department of State Lands - Emergency Authorization for Placement of Fill and Removal of Material in Waters of the State. In order to ensure all bidders are aware of these provisions, each bidder must sign this addendum below and attach it to the proposal. IMPORTANT: Failure to include a signed Addendum could result in the disqualification of your bid. Contractor’s Signature Date Company Name (please type or print) Document1 Addendum #1 - Appendix A 1 of 2 Department of State Lands Oregon 775 Summer Street NE, Suite 100 Kate Brown, Governor Salem, OR 97301-1279 (503) 986-5200 July 12, 2021 FAX (503) 378-4844 CPR600/63427 www.oregon.gov/dsl CITY OF ALBANY PO BOX 490 State Land Board ALBANY OR 97321 Kate Brown RE: EMERGENCY AUTHORIZATION FOR PLACEMENT OF FILL AND Governor REMOVAL OF MATERIAL IN WATERS OF THE STATE THIS AUTHORIZATION EXPIRES ON SEPTEMBER 7, 2021 Shemia Fagan Secretary of State • DSL Application No. 63427-RF • Site Address: 2391 & 2373 40th Ave SE Tobias Read • Santiam-Albany Canal, River Mile 3.2 and 7.7; Linn County State Treasurer • T. 11S, R. 03W, Section 20/25, Tax Lot 312,313/210, Albany Mr. Beathe: This letter is an authorization for emergency purposes only. An emergency is defined in Oregon Administrative Rule 141-085-0510(31) as “natural or human-caused circumstances that pose an immediate threat to public health, safety or substantial property including crop or farmland." Your request to conduct emergency repairs at two locations on the Santiam-Albany canal has been approved as an emergency authorization under ORS 196.810(4). -

Vote for One US Senator

5 PM 11/15/2016 General Unofficial results Election Report Marion County, Oregon Registered Voters Official General Election Official Ballot 134043 of 181657 = 73.79 % Run Time 4:46 PM 11/8/2016 Precincts Reporting Run Date 11/15/2016 Page 1 of 35 135 of 135 = 100.00 % United States President and Vice President - Vote for one Choice Party Election Day Voting Total Republican 61212 48.62 % 61212 48.62 % Donald J Trump Mike Pence Democrat 55267 43.89 % 55267 43.89 % Hillary Clinton Tim Kaine Pacific Green, 2732 2.17 % 2732 2.17 % Progressive Jill Stein Ajamu Baraka Libertarian 6698 5.32 % 6698 5.32 % Gary Johnson Bill Weld Cast Votes: 125909 100.00 % 125909 100.00 % Undervotes: 2465 2465 Overvotes: 163 163 Write-Ins: 5506 5506 US Senator - Vote for one Choice Party Election Day Voting Total Steven C Reynolds 3932 3.06 % 3932 3.06 % Independent Ron Wyden 63766 49.59 % 63766 49.59 % Democrat Mark Callahan 53480 41.59 % 53480 41.59 % Republican Eric Navickas 2206 1.72 % 2206 1.72 % Pacific Green, Progressive Jim Lindsay 1527 1.19 % 1527 1.19 % Libertarian Shanti S Lewallen 3680 2.86 % 3680 2.86 % Working Families Cast Votes: 128591 100.00 % 128591 100.00 % Undervotes: 5263 5263 Overvotes: 46 46 Write-Ins: 143 143 5 PM 11/15/2016 General Unofficial results Election Report Marion County, Oregon Registered Voters Official General Election Official Ballot 134043 of 181657 = 73.79 % Run Time 4:46 PM 11/8/2016 Precincts Reporting Run Date 11/15/2016 Page 2 of 35 135 of 135 = 100.00 % US Representative, 5th District - Vote for one Choice Party Election -

2012 Political Contributions

2012 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2012 Lilly Political Contributions 2 Public Policy As a biopharmaceutical company that treats serious diseases, Lilly plays an important role in public health and its related policy debates. It is important that our company shapes global public policy debates on issues specific to the people we serve and to our other key stakeholders including shareholders and employees. Our engagement in the political arena helps address the most pressing issues related to ensuring that patients have access to needed medications—leading to improved patient outcomes. Through public policy engagement, we provide a way for all of our locations globally to shape the public policy environment in a manner that supports access to innovative medicines. We engage on issues specific to local business environments (corporate tax, for example). Based on our company’s strategy and the most recent trends in the policy environment, our company has decided to focus on three key areas: innovation, health care delivery, and pricing and reimbursement. More detailed information on key issues can be found in our 2011/12 Corporate Responsibility update: http://www.lilly.com/Documents/Lilly_2011_2012_CRupdate.pdf Through our policy research, development, and stakeholder dialogue activities, Lilly develops positions and advocates on these key issues. U.S. Political Engagement Government actions such as price controls, pharmaceutical manufacturer rebates, and access to Lilly medicines affect our ability to invest in innovation. Lilly has a comprehensive government relations operation to have a voice in the public policymaking process at the federal, state, and local levels. Lilly is committed to participating in the political process as a responsible corporate citizen to help inform the U.S. -

102820Entireedition Pg

Bethany Republican-Clipper The official newspaper of Harrison County, Missouri since 1873 Bethany, Missouri 64424 Vol. 91, No. 39 www.bethanyclipper.com October 28, 2020 75 Cents Heavy turnout expected for presidential election Harrison County election of- ficials are expecting a heavy turnout for the General Elec- tion next Tuesday, Nov. 3, based upon record numbers filing ap- plications to vote absentee. The County Clerk’s office re- ported Monday that some 641 persons have applied for absen- Republican-Clipper photos tee ballots for the election. Some Neighborhood rivalry: Two neighbors living on the opposite 291 of those voters have already sides of Coleman Road in the Daily Addition have different opin- cast ballots at the clerk’s office ions about the presidential election. C. F. Rainey, left, supports in the courthouse. Donald Trump and Mike Pence while Curt Fletchall, right, backs The early voting trend reflects Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. Both said they have had their signs stolen and had to replace them in recent weeks. concerns about the pandemic and national interest in the presi- dential race between President election day. volve Jay Ashcroft, who is op- Donald Trump and Vice Presi- There also has been a great posed by Democrat Yinka Faleta dent Michael Pence, Republi- deal of interest in the gover- for re-election as secretary of cans, and their Democratic chal- nor’s race between incumbent state, incumbent Republican lengers former Vice President Mike Parson, a Republican, and state treasurer Scott Fitzpatrick Joe Biden and Senator Kamala Democrat Nicole Galloway who who is opposed by Democrat Harris. -

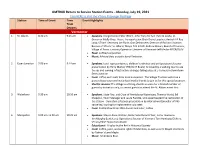

AMTRAK Return to Service Station Events

AMTRAK Return to Service Station Events – Monday, July 19, 2021 Click HERE to Visit the VTrans Passenger Rail Page Station Time of Event Time Event Highlights Train Departs Vermonter 1 St. Albans 8:30 am 9:15 am • Speakers: Congressman Peter Welch; John Tracy for Sen. Patrick Leahy; Lt. Governor Molly Gray; House Transportation Chair Diane Lanpher; Amtrak VP Ray Lang; VTrans’ Secretary Joe Flynn; Dan Delabruere, Director of Rail and Aviation Bureau of VTrans; St. Albans’ Mayor Tim Smith; Andrew Brown, Board of Trustees, Village of Essex Junction; Operation Lifesaver of Vermont-Jeff Medor-NECR/OLAV • Food: Coffee/tea/pastries. • Music: Minced Oats acoustic band-Tentative. 2 Essex Junction 9:00 am 9:44 am • Speakers: Local representatives, children’s activities and an Operation Lifesaver presentation by Perry Martel, VRS/OLVT Board, followed by a walking tour to see the up-and-coming infrastructure changes taking place at 5 Corners in Downtown Essex Junction • Food: coffee and treats from local businesses. The Village Trustees will issue a press release soon and invite local media friends to join us for this special occasion. • Shuttle services: The Village is offering shuttle services for a limited number of guests by invitation only, to permit guests to attend the St. Albans event first. 3. Waterbury 9:30 am 10:10 am • Speakers: State Rep. and Chair of Revitalizing Waterbury, Theresa Wood; Bill Shepeluk, Town Manager and Laura Parette, who spearheaded the restoration of the station. Operation Lifesaver presentation by Alex Schwartzmueller of VRS cancelled, looking for replacement volunteer. • Food: Cold Hollow Cider Mills donuts and cider; coffee 4. -

S/L Sign on Letter Re: Rescue Plan State/Local

February 17, 2021 U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Members of Congress: As elected leaders representing communities across our nation, we are writing to urge you to take immediate action on comprehensive coronavirus relief legislation, including desperately needed funding for states, counties, cities, and schools, and an increase in states’ federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP). President Biden’s ambitious $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan will go a long way towards alleviating the significant financial strain COVID-19 has placed on our states, counties, cities, and schools, and the pocketbooks of working families. Working people have been on the frontlines of this pandemic for nearly a year and have continued to do their jobs during this difficult time. Dedicated public servants are still leaving their homes to ensure Americans continue to receive the essential services they rely upon: teachers and education workers are doing their best to provide quality education and keep their students safe, janitors are still keeping parks and public buildings clean, while healthcare providers are continuing to care for the sick. Meanwhile, it has been ten months since Congress passed the CARES Act Coronavirus Relief Fund to support these frontline workers and the essential services they provide. Without significant economic assistance from the federal government, many of these currently-middle class working families are at risk of falling into poverty through no fault of their own. It is a painful irony that while many have rightly called these essential workers heroes, our country has failed to truly respect them with a promise to protect them and pay them throughout the crisis. -

Candidate Office District Position Division Party Title First Name

Candidate Office District Position Division Party Title First Name Middle Last Name Suffix Home Address City Zip Mailing Address City Zip Home Phone Work Phone Cell Phone Email Web Address Date Filed Ballot City Running Mate Ballot City Joseph R. Biden / Kamala D. Harris President / Vice President 0 0 0 Democratic Mr. Joseph R. Biden 1209 Barley Mill Road Wilmington 19807 8/20/2020 Wilmington, DE Los Angeles, CA Donald J. Trump / Michael R. Pence President / Vice President 0 0 0 Republican Mr. Donald J. Trump 1100 S. Ocean Blvd. Palm Beach 33480 9/2/2020 Palm Beach, FL Indianapolis, IN Jo Jorgensen / Jeremy "Spike" Cohen President / Vice President 0 0 0 Libertarian Ms. Jo Jorgensen 7/21/2020 Greenville, SC Little River, SC Barbara Bollier United States Senate 0 0 0 Democratic Dr. Barbara Bollier 6910 Overhill Road Mission Hills 66208 [email protected] www.bollierforkansas.com 5/11/2020 Mission Hills Roger Marshall United States Senate 0 0 0 Republican Dr. Roger Marshall P.O Box 1588 Great Bend 67530 [email protected] kansansformarshall.com 5/18/2020 Great Bend Jason Buckley United States Senate 0 0 0 Libertarian Jason Buckley 8828 Marty Ln Overland Park 66212 (816) 678-7328 [email protected] 5/28/2020 Overland Park Kali Barnett United States House of Representatives 1 0 0 Democratic Ms. Kali Barnett 410 N 6th St #957 Garden City 67846 (620) 277-9422 [email protected] www.kaliforkansas.com 5/21/2020 Manhattan Tracey Mann United States House of Representatives 1 0 0 Republican Mr. Tracey Mann PO Box 1084 Salina 67402 (785) 236-7802 www.traceymann.com 5/27/2020 Salina Michelle De La Isla United States House of Representatives 2 0 0 Democratic Ms. -

Race, Gender and Immigration in American Politics by Christian

Expansion and Exclusion: Race, Gender and Immigration in American Politics By Christian Dyogi Phillips A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Rodney Hero, Co-Chair Professor Taeku Lee, Co-Chair Professor Lisa García Bedolla Professor Gabriel Lenz Summer 2017 Abstract The United States’ population is rapidly changing, but the ways in which political scientists measure and understand representation have not kept apace. Marginal shifts in descriptive representation over the past two decades have run counter to widely espoused ideals regarding political accessibility and democratic competition. A central assumption often made by academics, and the public, has been that groups which are otherwise disadvantaged in politics may leverage their communities’ numerical size as a political resource to gain influence. To this end, many studies of racial descriptive representation find that a larger minority population is associated with a higher likelihood of a racial minority running for and/or winning. However, these positive relationships between population growth and descriptive representation are tempered by an extensive literature documenting limits on racial minority groups’ political incorporation. Moreover, current frameworks for understanding group competition or patterns of descriptive representation are silent about whether shifts in racial demographics may also have an effect on the balance of representation between women and men. These contradictions in debates over representation, and how groups gain influence, undermine the notion that eventually, marginalized groups will be fully incorporated into politics. White women have had de jure access to the voting franchise in the United States since 1920. -

Hereby Halt the Proposed

No. __-___ In the Supreme Court of the United States ____________________________________________________ KELI’I AKIN, KEALII MAKEKAU, JOSEPH KENT, YOSHIMASA SEAN MITSUI, PEDRO KANA’E GAPERO, and MELISSA LEINA’ALA MONIZ, Applicants, v. THE STATE OF HAWAII, GOVERNOR DAVID Y. IGE, ROBERT K. LINDSEY JR., Chairperson, Board of Trustees, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, COLETTE Y. MACHADO, PETER APO, HAUNANI APOLIONA, ROWENA M.N. AKANA, JOHN D. WAIHE’E IV, CARMEN HULU LINDSEY, DAN AHUNA, LEINA’ALA AHU ISA, Trustees, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, KAMANA’OPONO CRABBE, Chief Exec. Officer, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, JOHN D. WAIHE’E III, Chairman, Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, NA’ALEHU ANTHONY, LEI KIHOI, ROBIN DANNER, MAHEALANI WENDT, Commissioners, Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, CLYDE W. NAMU’O, Exec. Director, Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, THE AKAMAI FOUNDATION, and THE NA’I AUPUNI FOUNDATION, Respondents. ______________________________________________________________________________ APPENDIX ___________________________________________________________________________ Michael A. Lilly Robert D. Popper, Counsel of Record NING LILLY & JONES JUDICIAL WATCH, INC. 707 Richards Street, Suite 700 425 Third Street, SW Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Washington, DC 20024 (808) 528-1100 (202) 646-5172 [email protected] [email protected] H. Christopher Coates William S. Consovoy LAW OFFICES OF H. CHRISTOPHER COATES J. Michael Connolly 934 Compass Point CONSOVOY MCCARTHY PARK PLLC Charleston, South Carolina 29412 3033 Wilson Boulevard (843) 609-7080 Arlington, Virginia 22201 [email protected] (703) 243-9423 www.consovoymccarthy.com Dated: November 23, 2015 Attorneys for Applicants Case 1:15-cv-00322-JMS-BMK Document 122 Filed 11/19/15 Page 1 of 2 PageID #: 1667 FILED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS NOV 19 2015 MOLLY CC. -

Kansas State Representatives and Senators

Kansas State Representatives and Senators If you would like to mail your representative please use the following form: Representative or Senator Name 6425 SW 6th Avenue Topeka, KS 66615’ Kansas State Representatives Legislator Name Special Notes and Contact Info Committees: Transportation and Public Safety Budget; Insurance; Elections Bio: Teacher in the Olathe School District Contact Info: Room 451-S Phone: 785-296-5413| Email: [email protected] Rep. Brett Parker [D-29] District Boundaries: Johnson County Committees: Health and Human Services; Joint Committee on Pensions, Investments and Benefits; Federal and State Affairs Contact Info: Room 451-S Phone: 785-296-7697| Email: [email protected] District Boundaries: Wyandotte County Rep. Broderick Henderson [35] Committees: Elections Committee Chair; Veterans and Military; Social Services Budget; Joint Committee on Information Technology’; Government, Technology and Security Bio: Software Engineer Contact Info: Room 151-S Phone: 785-296-7688 | Email: [email protected] Rep. Keith Esau [14] District Boundaries: Johnson County Committees: Health and Human Services; Interstate Cooperation; Water and Environment Contact Info: Room 173-W Phone: 785-296-7659| Email: [email protected] District Boundaries: Johnson County Rep. Cindy Holscher [D-16] Committees: General Government Budget; Agriculture Contact Info: Room 43-S Phone: 785-296-7659 | Email: [email protected] District Boundaries: Johnson County Rep. Cindy Neighbor [D-18] Committees: Joint Committee on Special Claims Against the State, Vice-Chair; Legislative Budget, Vice-Chair; Appropriations, Vice-Chair; Joint Committee of Corrections and Juvenile Justice; Taxation; 2016 Special Committee of Foster Care Adequacy Rules and Journal; Commerce, Labor and Economic Development Bio: Attorney Contact Info: Room 151-S Phone: 785-296-7659 | Email: [email protected] Rep. -

Kansas Senate

In accordance with Kansas Statutes, the following candidates have been recommended by the Committee on Political Education of AFT-Kansas (KAPE COPE) for the 2016 General Election: Please note, where there is no candidate listed, a recommendation has not been made. Kansas Candidates below whose names are highlighted will face a general election opponent. A Union of Candidates below whose names are in blue are recommended Professionals but do NOT have a general election opponent. Kansas State Board of Education: District 2 Chris Cindric (D) District 4 Ann Mah (D) District 6 Aaron Estabrook (I) Deena Horst (R) District 8 District 10 Kansas Senate: SD 1 Jerry Henry (D) SD 15 Dan Goddard (R) SD 27 Tony Hunter (D) SD 2 Marci Francisco (D) Chuck Schmidt (D) SD 28 Keith Humphrey (D) SD 3 Tom Holland (D) SD 16 Gabriel Costilla (D) SD 29 Oletha Faust-Goudeau (D) SD 4 David Haley (D) SD 17 Susan Fowler (D) SD 30 Anabel Larumbe (D) SD 5 Bill Hutton (D) SD 18 Laura Kelly (D) SD 31 Carolyn McGinn (R) SD 6 Pat Pettey (D) SD 19 Anthony Hensley (D) SD 32 Don Shimkus (D) SD 7 Barbara Bollier (R) SD 20 Vicki Schmidt (R) SD 33 SD 8 Don McGuire (D) SD 21 Logan Heley (D) SD 34 SD 9 Chris Morrow (D) Dinah Sykes (R) SD 35 SD 10 Vicki Hiatt (D) SD 22 Tom Hawk (D) SD 36 Brian Angevine (D) SD 11 Skip Fannen (D) SD 23 Spencer Kerfoot (D) SD 37 SD 12 SD 24 Randall Hardy (R) SD 38 SD 13 Lynn Grant (D) SD 25 Lynn Rogers (D) SD 39 John Doll (R) SD 14 Mark Pringle (D) SD 26 Benjamin Poteete (D) SD 40 Alex Herman (D) Kansas House of Representatives: HD 1 HD 43 HD 85 Patty -

Mayors Representing 1.3 Million Constituents in Wisconsin Call on Secretary Andrea Palm to Act Quickly and Decisively to Prevent Further Spread of COVID-19

Mayors Representing 1.3 Million Constituents in Wisconsin call on Secretary Andrea Palm to act Quickly and Decisively to Prevent Further Spread of COVID-19 As leaders of communities throughout Wisconsin, we write to ask you to exercise the emergency powers delegated to you under section 252.02 of the Wisconsin State Statutes. We implore you to implement all emergency measures necessary to control the spread of COVID-19, a communicable disease. Specifically, we need you to step up and stop the State of Wisconsin from putting hundreds of thousands of citizens at risk by requiring them to vote at the polls while this ugly pandemic spreads. This request is urgent because, as you know, Wisconsin’s April primary election is scheduled for this Tuesday, April 7. We believe it would be irresponsible and contrary to public health to conduct in-person voting throughout the state at the very time this disease is spreading rapidly. Over 1,350,000 people live in our communities and we need you to provide leadership. We thank Governor Evers for the leadership he demonstrated when he declared a state of emergency via Emergency Order #12. We thank him for calling a special session to address this issue. In light of the Legislature’s inexcusable refusal to act, you and your department now are the sole parties in the position to prevent hundreds of thousands of voters and poll workers from potentially being exposed needlessly to this worldwide pandemic. In his decision just days ago, Judge Conley recognized the important role you play when he said, “As much as the court would prefer the Legislature and Governor consider the public health ahead of any political considerations, that does not appear in the cards.